David Hilliard Wide-Screen Tableaux

WORK AND PROCESS

Bill Arning

In his multipanel photographs, David Hilliard constructs cinematic narratives that, although they may derive from his particular social relations, speak of the larger experience of trying to understand how one may belong in the world. His perspective is empathetic yet distanced, loving yet critical. Across his wide-screen tableaux, actors perform familiar dramas—often no more strange than gardening or exercising—but with a certain theatricality that makes us aware of an oddness in the scene. Hilliard’s cast of characters comprises actual family, friends, and lovers, as well as surrogate players for those that are not available to be photographed— including Hilliard’s childhood self. These are the characters from whom we can never get enough distance to comprehend fully (despite piles of psychotherapy bills). Yet in identifying with the players from Hilliard’s intimate memories, we may more wisely consider those in our own photo albums.

Hilliard’s vision is clearly autobiographical, and thankfully he doesn’t pander to the myth of universality by pretending that it is not. His stories are of the life of a gay white male, who today enjoys a certain privilege in comparison with his working-class background—but who is never fully comfortable in his skin. This is most obvious in Hilliard’s photographs of family. Gay men’s relationships with their fathers are often fraught with complication, and some of Hilliard’s most celebrated works star his father—such as What the Ice Gets, The Ice Keeps (1999), in which his shirtless father reveals the oddly sweet tattoos of little birds across his chest. Hilliard himself has recently had the identical birds tattooed on his own chest—an act that is somehow emblematic of the depth of his urge to identify with those who populate his intimate world.

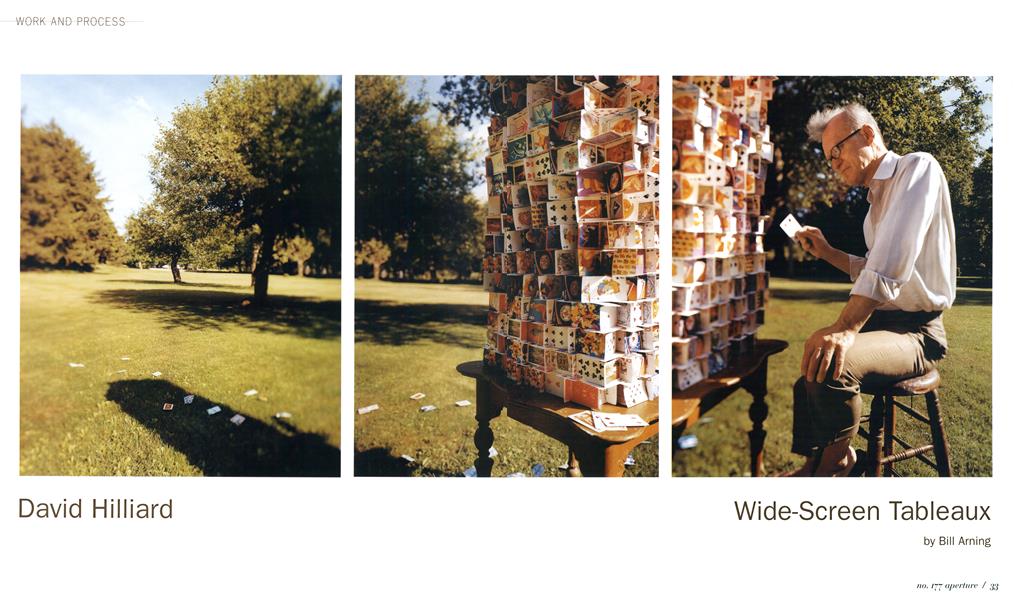

Hilliard’s work is a hybrid of highly staged photographs requiring great planning—several feature an absurdly tall house of cards—and images apparently captured on the fly, inspired by fortuitous encounters. Such free mixing is unusual in an artworld context that often forces photographers to choose camps early in their careers and never deviate. The mix also creates a destabilizing effect on the viewers’ tendency to look for concrete biographical truth in Hilliard’s narrative hall of mirrors.

This “hybrid” practice is further reflected in Hilliard’s chosen presentation format: polyptychs of mid-scale discrete photographs, hung about an inch apart, each total work consisting of two to four panels. By constructing his tableaux out of these chunks, the gaps between them take on significance, foregrounding the fact that each picture in the grouping—perfectly composed as an individual image—functions in the service of a larger theme. The viewer is aware that the pictures in the group could not have been taken at the same instant, and this leads us to consider the temporal gap between the scenes. The amount of time between exposures is not known; it is somewhere between adjoining film frames, between adjoining memories. In some works, this timedisparity between images becomes a focus in itself. In Tug of War (2003), for example, the same figure appears in two interacting photographs, pulling on opposite ends of a single piece of cloth; the gap here is the space of fiction and metaphor—wittily contradicted by the right-hand contestant’s shadow falling across the border into the left figure’s zone. In Swimmers (2003), Hilliard has created an artful homage to Thomas Eakins’s photographic studies for his swimminghole paintings—works that today seem so over-the-top in their hothouse homoeroticism that one wonders how they could have been made in the 1880s. Yet Hilliard’s version conjures the aura of wistfulness in Eakins’s images: consider the center portrait of the boy who does not join the other swimmers for their summer idyll. It is left to us to contemplate why the boy doesn’t join in—although, because the other swimmers are in a separate photograph, they may not be sharing the same space or time at all. One might project onto the lone boy mere shyness, or discomfort due to the transgressiveness of his burgeoning desires. Or perhaps this is simply the memory of lost joys and moments of the long summers of adolescence.

This theme of the outsider is the leitmotiv of many of Hilliard’s works. Pretty White Things (2003) features a boy who seems to live in a dream-world with his white mice and unicorn friends. It is clear that this character is more likely to save drowning beetles than to abuse innocent creatures, and has therefore already separated himself from the rituals of his testosterone-addled peers. The star of Hulk (2003), on the other hand, is clearly more an object of desire than a touchstone for our identification—a tough and unapproachable beauty, posing at a low-rent carnival. But here, too, Hilliard gives us a few metaphorical clues about the protagonist’s inner existence. The inflatable Hulk doll at left is a burly but empty shell—just as the man is still a boy, wrapped in muscle and other masculine signifiers. The same Hulk character, in his comic book, TV, or cinematic form, may also have helped to shape that boy’s own identity.

The distance so characteristic of Hilliard’s work does not disappear when the subject is familial relations—but it does change shape. One’s family is always psychologically nearby, even when they are dispersed or gone, which makes their ultimate unknowability even more frustrating. In Inspection (2003), the world of Hilliard’s mother is shown to be not unlike that of the boy with the mice, in that it is starkly delimited, even claustrophobic in its scope. Her head is down, and we see only her curlers—as pink as the flowers she probes for bugs—and her obsessiveness becomes clear to the viewer. The retiree’s hobby in 100 Decks (2003) is likewise absurd—although precisely the type of strange avocation often chosen by those who have left behind the careers that defined them. This archetypal father still manages something: this futile effort to build a durable structure out of a hodgepodge of cards—hopelessly exposed to the elements. The image comments metaphorically on the experience of people in their later years, when all that they have worked to achieve begins to blow away and lose meaning. They are left only with puerile entertainments and the simplest of pleasures—such as those enjoyed by the two elderly protagonists in Hot Coffee, Soft Porn (1999). Should we envy these retirees for their unstructured schedules, or pity them for wasting their remaining time with sugar rushes and vague titillations? So many of us turn away from an awareness of that impending stage; in order to get on with our lives, we move forward convincing ourselves that it all matters greatly, terrified even to imagine ourselves still in pajamas at noon.

What might indeed matter in the end is whether, during the transit though this life, we manage to make real connections in the world. This struggle for connection propels each of Hilliard’s psychologically complex narratives, and makes them amply repay the attention they demand. ©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Archive

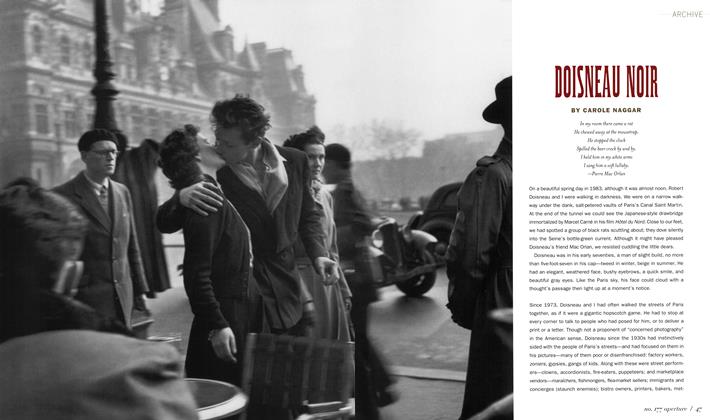

ArchiveDoisneau Noir

Winter 2004 By Carole Naggar -

On Assignment

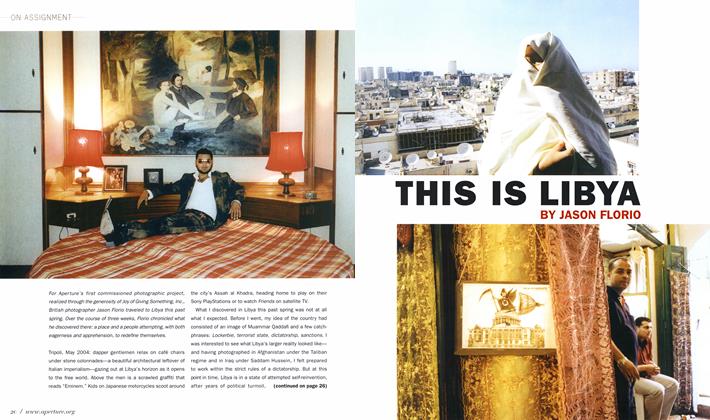

On AssignmentThis Is Libya

Winter 2004 By Jason Florio -

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectRinko Kawauchi Utatane

Winter 2004 By Charlotte Cotton -

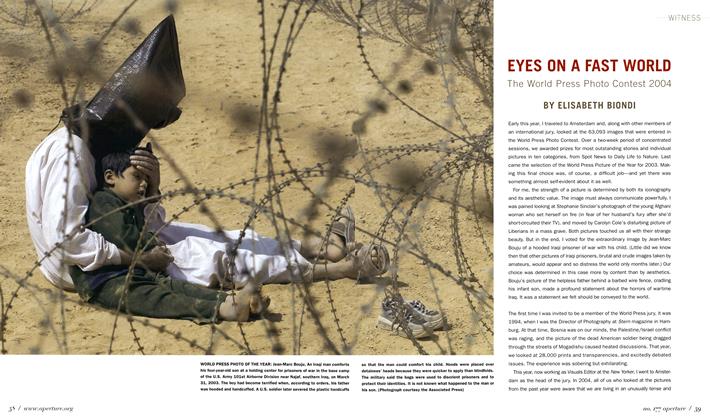

Witness

WitnessEyes On A Fast World The World Press Photo Contest 2004

Winter 2004 By Elisabeth Biondi -

Book Excerpts

Book ExcerptsGeoffrey Batchen: Forget Me Not: Photography & Remembrance

Winter 2004 By Geoffrey Batchen -

Book Excerpts

Book ExcerptsBruno Stevens: Baghdad: Truth Lies Within

Winter 2004 By Jon Lee Anderson

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Work And Process

-

Work And Process

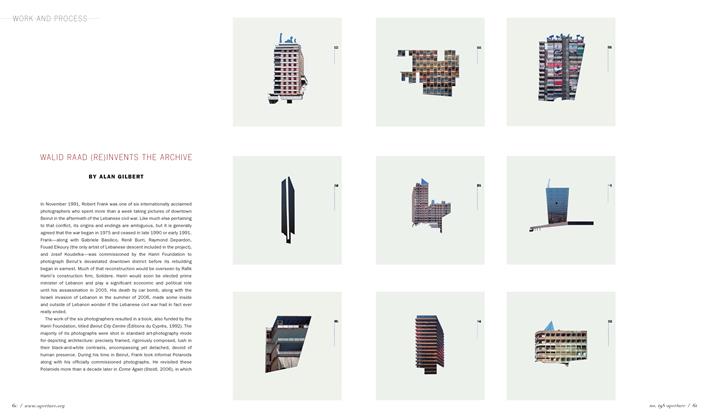

Work And ProcessWalid Raad (re)invents The Archive

Spring 2010 By Alan Gilbert -

Work And Process

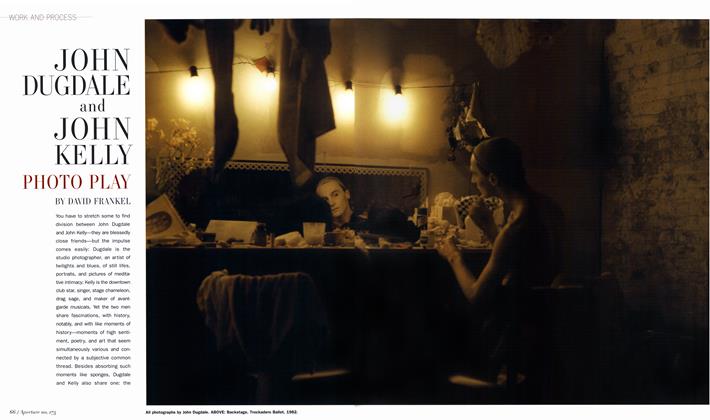

Work And ProcessJohn Dugdale And John Kelly

Winter 2003 By David Frankel -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessEsteban Pastorino Diaz: A View From Somewhere

Winter 2005 By Fernando Castro -

Work And Process

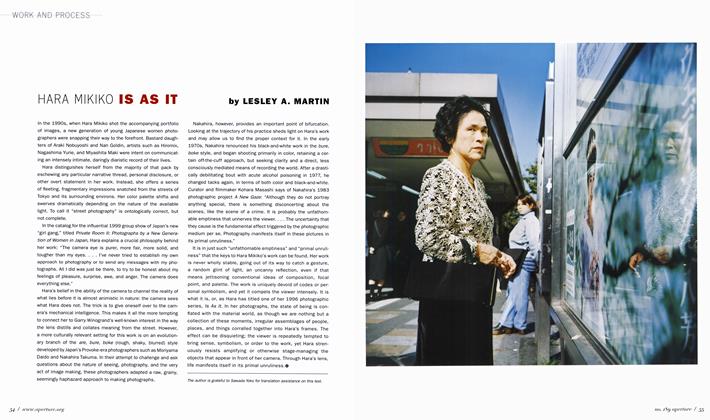

Work And ProcessHara Mikiko Is As It

Winter 2007 By Lesley A. Martin -

Work And Process

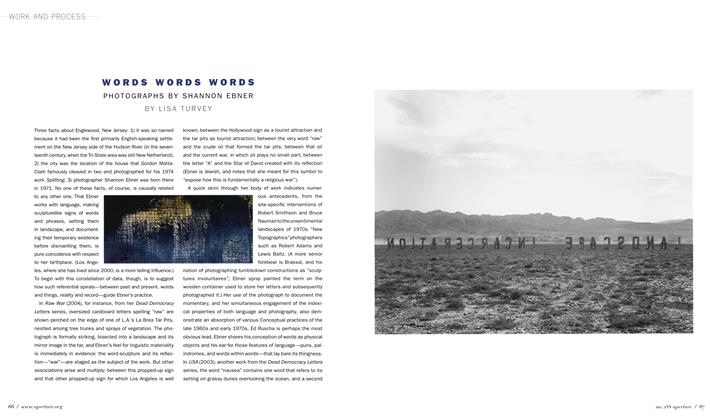

Work And ProcessWords Words Words: Photographs By Shannon Ebner

Fall 2007 By Lisa Turvey -

Work And Process

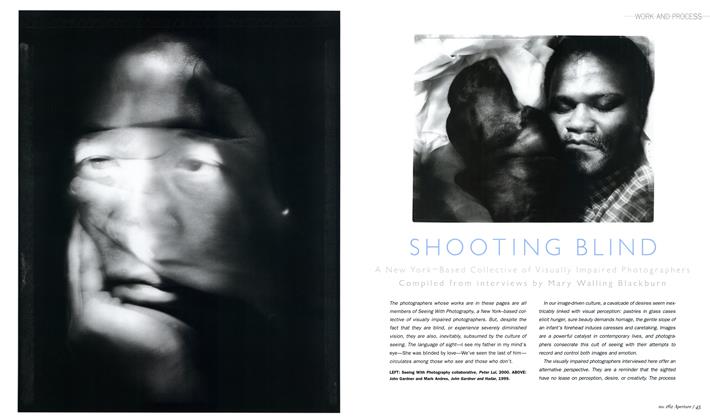

Work And ProcessShooting Blind

Winter 2001 By Mary Walling Blackburn