JANE HAMMOND'S RECOMBINANT DNA

WORK AND PROCESS

Amei Wallach

Jane Hammond came of artistic age as the 1970s morphed into the 1980s, a time when artists of every stripe were diagnosing the contagion of secondhand images that infects the ways we see ourselves. Many artists turned to photography, a medium complicit in the situation, for their critique. Cindy Sherman photographed herself as women in the thrall of B-movie pipedreams. Barbara Kruger’s texts told you what not to think about what you thought you were seeing in her appropriated photographs.

Jane Hammond kept on painting, because for her all that visual static out there in magazines and newspapers, on televisions and movie screens, was simply the landscape of everyday life, like daffodils to Wordsworth or taxicabs to Frank O’Hara.

“I grew up in a world of mediated imagery,” she says. “How am I going to be an imaginative, spirited, authentic, private, living, breathing self? How do I shape this stuff?” In her paintings and prints, for nearly three decades, she has shaped it with Big Tent inclusiveness. She foraged flea markets, used-book stores, and antique shops for prints, stamps, tattoos, cartoons, refrigerator magnets, and illustrations out of molecular-biology, phrenology, and physics books. Her interest from the start has been in “how meaning is constructed,” as she puts it, particularly if that meaning is a private re-imagining of public information.

For many years Hammond limited herself to 276 specific found images, which she disengaged from their various contexts, altered in scale, and reshuffled. A red lotus became a medallion in a doily border, in concert with Gandhi’s face, a blue rabbit, and a set of dice in her painting Bread and Butter Machine (2000); it colonized the sole of a foot in the double cutout painting Sore Models #2 (1994); it marked the spot where Hammond lives on a detail from a New York City map—also enigmatically decorated with a mouse, a shoe, a woman on a trapeze—in The Wonderfulness of Downtown (1997).

Suddenly, three years ago, Hammond began applying her scavenging, recombinant sensibilities to photography. The resulting images are and are not heirs to the photomontage traditions of Russian Constructivism, Dada, and John Heartfield. They are neither political nor fragmented, though they share a strain of theatricality with the Surrealist Max Ernst. Hammond doesn’t so much collage her images as re-contextualize them. They create their own narratives, alternate universes that appear seamless no matter how bizarre the associations or elaborate the effects. As a painter does with colors, Hammond alters weight, hue, and meaning through juxtapositions.

In the fall of 2004, Hammond was investigating frogs in every imaginable medium for her Scrapbook series of paintings and prints. She had already found a frog rubber stamp and had made a rayogram from a frog skeleton. She wanted a frog photograph. By now she often let the Internet do her walking, and she typed in “frog.” Then she typed in words for images she’d riffed on in her paintings—like “snowman.” She found images of World War II soldiers bayoneting Hitler snowmen for target practice, sexy women snowgirls at the Dartmouth Winter Carnival, and one diminutive snowman from a rare Southern winter.

That December, on her studio floor, she sorted selections from her growing collection of over a thousand photographs by classification. And then she went off to fix supper. Like a song, in her mind, a particular photograph kept repeating—it was “the kind of black-and-white photograph your mother had on the dresser,” she says. When she realized that the photograph in her mind was actually a sampling of details from many photographs, she had embarked on what to date has resulted in forty-five photographs and two bulletin-board snapshot compositions.

Hammond had always, in a sense, been collaborating with the culture in which she lived. She now began collaborating with a series of anonymous photographers and with the Internet. “This has been my thing: recombinant DNA,” she says. “Searching, linking, all this stuff—it’s like a wave; it’s perfect for me to ride on.”

One of Hammond’s first photographs, Perpetual Love (2005), resulted from her desire to make a still life. She needed a table to put it on. She typed in “ping-pong” and discovered a genre of S and M called “ping-pong bondage,” in which participants spank each other with ping-pong paddles. The act of bondage replaces the still life in the classic Renaissance triangle she has constructed from a postwar British photograph of two girls playing ping-pong without net or ball in a bombed-out setting whose details are borrowed and reconfigured, including the insertion at the apex of the triangle of a bare bottom being paddled.

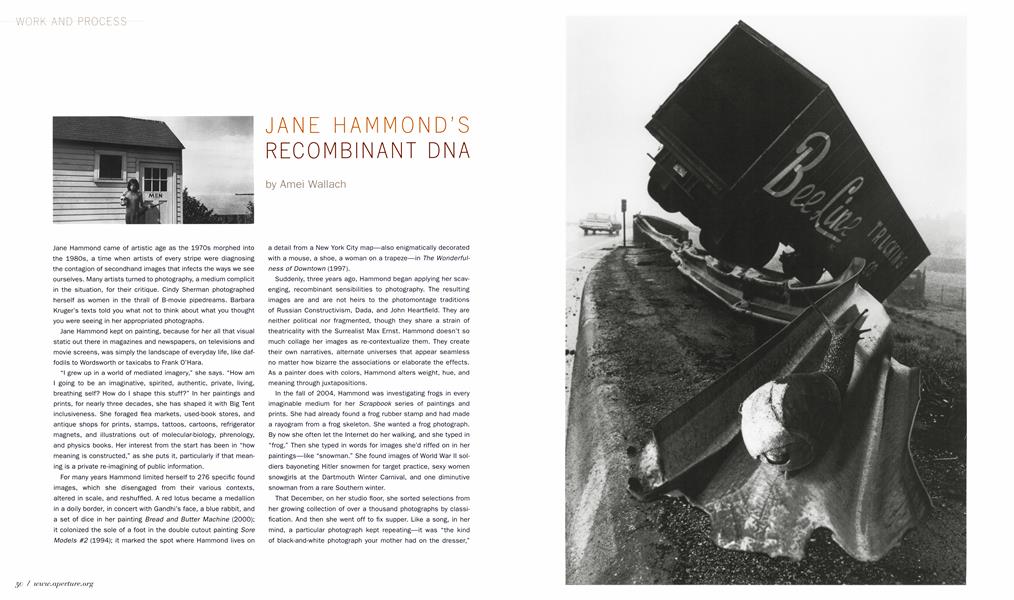

Bee Line Trucking (2005), one of Hammond’s most effective photographs, collapses eras and styles. It evokes American Abstract Expressionism as well as the whole history of Soviet art. The crashed Bee Line truck slashes into space like one of Kazimir Malevich’s painted semaphores, which the Socialist Realists would later translate into heroic trains. The trains, in turn, were appropriated into the irony of 1980s Moscow Conceptualism. It’s not only time that Hammond is jamming here, it’s duration and speed. The stopped truck, the departing car, the crawling snail are all made more palpable through formal devices derived from her painting practice.

At the same time, Hammond plays with the inherent qualities of photography, such as its believable tactility. You know the feel of the underwear and towels—from other times and other photographs—that hang over stacked balconies in the hallucinatory images Chai Wan (2005) and Chai Wan Two (2006). You’ve touched the dancer’s satiny costume, the grit on the rusting gridded window bars.

Hammond works her images digitally, coilaging, retouching, building shadows in cyberspace. The resulting digital file is converted to a negative, which is printed in a darkroom as a selenium-toned gelatinsilver photograph. It is the silver gelatin that makes an aesthetic whole of the photographs, no matter how aberrant their parts, and renders them slightly archaic (like the idea of what the word “photograph” meant when Hammond was growing up in the 1950s). This is particularly true of Mechanic Falls (2005). There are aspects of Edward Hopper in the austerity of the architecture and in the woman ready to greet someone at the door. But then there are the lizards dangling from a clothesline to destabilize it all, rendering this a scene out of Hitchcock’s Psycho, in which the woman might be Tony Perkins and everything is about to go horribly wrong.

This sense of other readings, other roads, permeates a very different photo-collage made in 2007, an untitled 42-by-108-inch compendium of black-and-white snapshots (and one faded color photograph) into which Hammond has inserted her own face. She has done this often in paintings and prints, as if trying on the emotional weight of her disjointed narratives. Here she is the boy, the girl, the neighbor pointing a camera; the bride atop the wedding cake; the trick rodeo rider, fat lady, hunter, Japanese wife. She is living out the what-ifs the camera makes instantly available. She has altered the corners of the digital prints so they might be snapshots torn out of a scrapbook. Sometimes their edges are scalloped, their contrast sharp or bland, their black-and-white a declension of what black-and-white can mean. Dispersed over the horizontal surface, they are reminiscent of how she once composed her range of found printed images from old French cookbooks, taxidermy how-to manuals, and shadow-puppet plays.

A vernacular photograph is different, though. It is a sense memory into a scene someone actually lived. And it has opened a million possibilities for an artist who has always thought of herself as a painter. This is just the beginning.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Essay

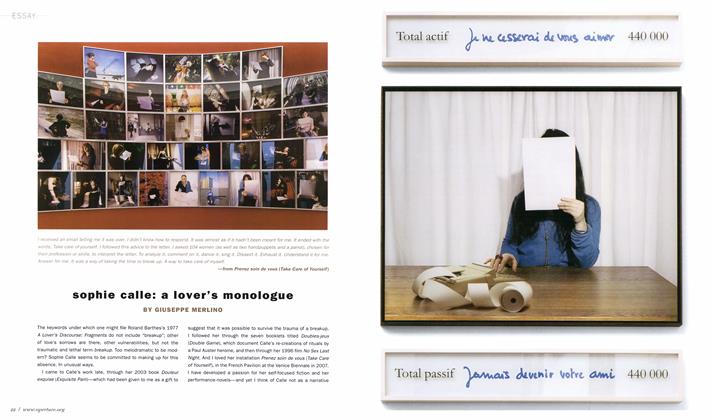

EssaySophie Calle: A Lover's Monologue

Summer 2008 By Giuseppe Merlino -

Work In Progress

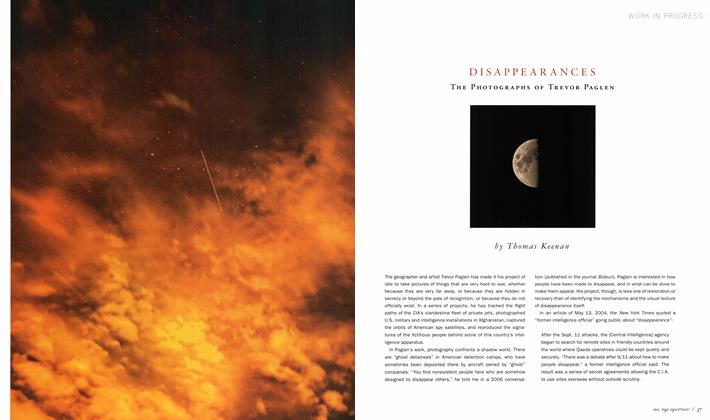

Work In ProgressDisappearances The Photographs Of Trevor Paglen

Summer 2008 By Thomas Keenan -

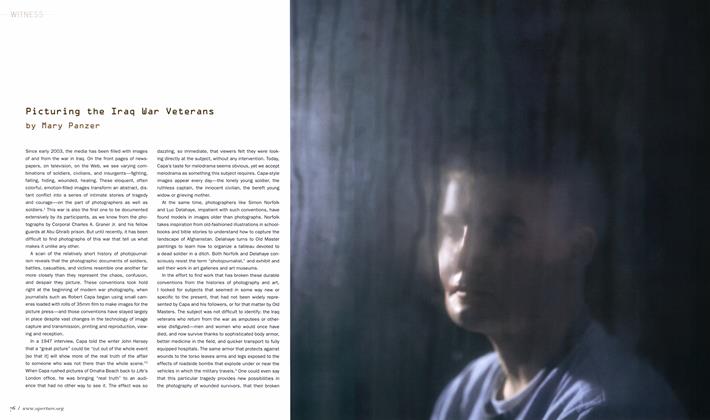

Witness

WitnessPicturing The Iraq War Veterans

Summer 2008 By Mary Panzer -

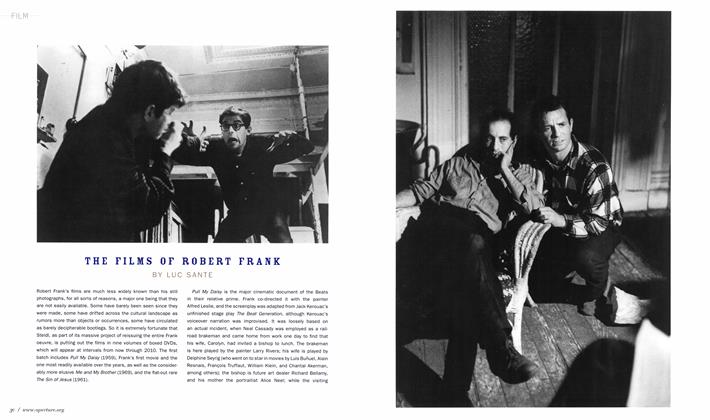

Film

FilmThe Films Of Robert Frank

Summer 2008 By Luc Sante -

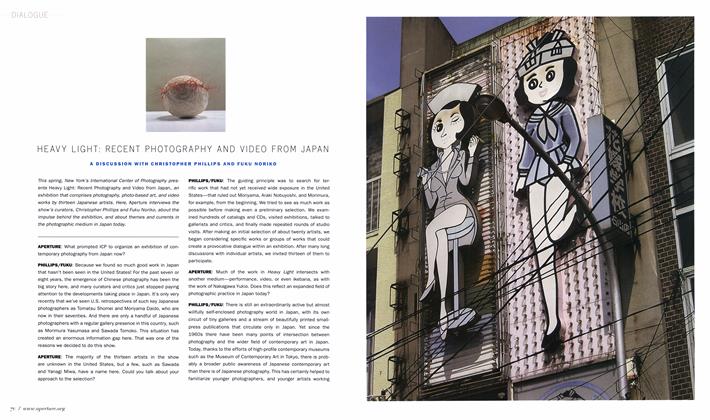

Dialogue

DialogueHeavy Light: Recent Photography And Video From Japan

Summer 2008 -

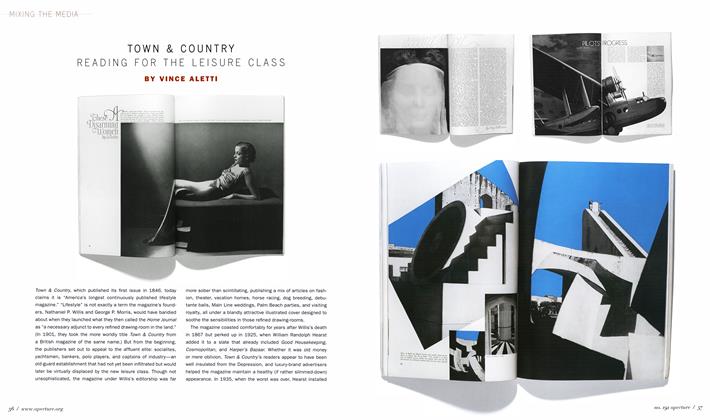

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaTown & Country Reading For The Leisure Class

Summer 2008 By Vince Aletti

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Work And Process

-

Work And Process

Work And ProcessInstant Gratification

Spring 2001 By Arthur C. Danto -

Work And Process

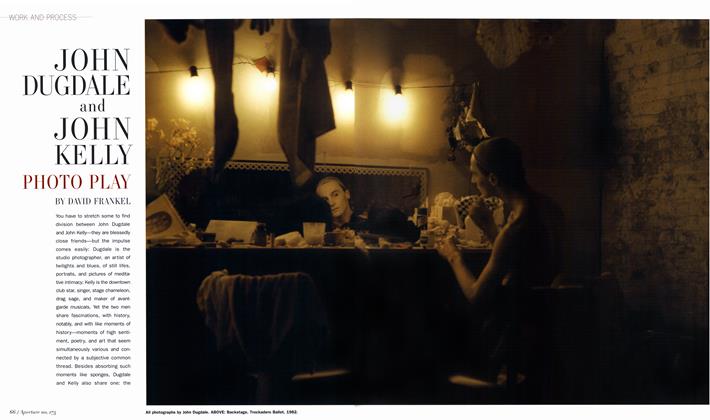

Work And ProcessJohn Dugdale And John Kelly

Winter 2003 By David Frankel -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessLoretta Lux's Changelings

Spring 2004 By Diana C. Stoll -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessThe Unblinking Judy Linn

Summer 2012 By Francine Prose -

Work And Process

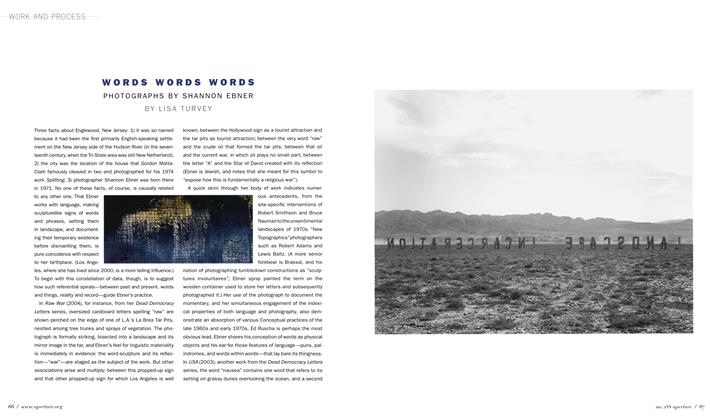

Work And ProcessWords Words Words: Photographs By Shannon Ebner

Fall 2007 By Lisa Turvey -

Work And Process

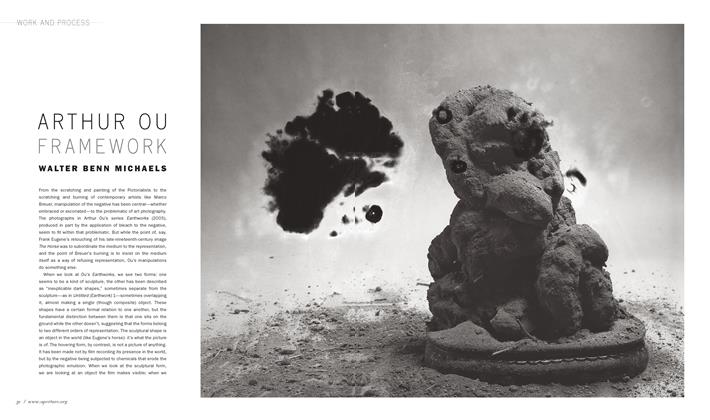

Work And ProcessArthur Ou Framework

Spring 2012 By Walter Benn Michaels