Dispatches

Sri Lanka

In a postcolonial society, artists contend with official fictions

Winter 2018 Jyoti DharSri Lanka

Dispatches

In a postcolonial society, artists contend with official fictions

Jyoti Dhar

In March 2018, in the popular tourist district of Kandy, Sri Lanka, a road-rage incident between a Buddhist man and a group of Muslim men unexpectedly escalated into days of mob violence. Religious extremist groups manipulated the incident and used it as an opportunity to spread hate speech, resulting in President Maithripala Sirisena imposing a state of emergency on the island nation, the first since the end of the civil war, nearly a decade ago, in 2009.

But Kandy, or Kanda Uda Rata, as it was known before British colonization, is no stranger to the distortion of histories or the jostling of ideologies. Its dynastic kingdom was the country’s seat of power and religion from the fifteenth to the nineteenth century, staving off successive attacks from local factions and European colonizers alike until it fell to the British in 1815. Though it has been seventy years since Sri Lanka gained independence from Britain, in 1948, successive waves of nationalist movements, giving voice to claims of authenticity or legitimacy of one ethnic group over the other, continue to surface.

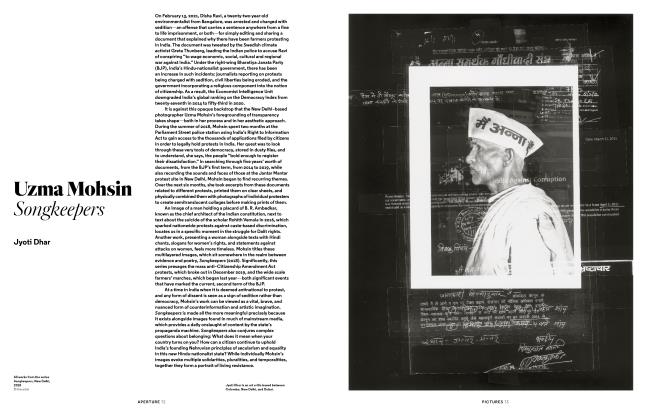

In the last few decades, several contemporary artists have engaged with Sri Lanka’s past and present, focusing on the ways that such claims are constructed and truths are doctored. In Royal Couple (2015), a diptych of portraits by Rajni Perera, the country’s clash with colonialism, and the resulting coexistence of cultures and identities, finds apt expression. For Perera, who was born in Sri Lanka and raised in Toronto, the series “created an opportunity to analyze my relationship with colonial ideology, being an immigrant in a colony, and revisiting my colonized country of birth,” she told me recently.

One of the two portraits, Greed, depicts a king in all his finery, seated in a gilded chair. The incongruity of his supposedly macho appearance is brought into sharp relief by his fire-red fingertips, dyed and decorated like a bride’s. But that bearded and mustachioed face is, in fact, the artist herself, surrounded by a medley of motifs: the Dutch East India Company’s cipher, upholstery in a kitschy tropical print, and a backdrop of elegant wallpaper patterned with flowers symbolizing the Orient and Occident. Perera’s reenactments transform Sri Lankan mystical narratives for an anxious, alienated present and challenge the idea of kingship as an incarnation of purity, divinity, and paternal authority.

In the last few decades, several contemporary artists have engaged with Sri Lanka’s past and present.

For Cassie Machado, who, like Perera, was born in Sri Lanka but grew up abroad, photography is a way to decipher her sense of diasporic identity. Machado fled the island as a child during the anti-Tamil pogrom known as the Black luly riots of 1983, which triggered the twenty-six-year civil war. “I needed to return to the conflict if I was to understand the psychology and cultural makeup of this country,” Machado says. “The story I wanted to tell was about the end of the war, those traumas and atrocities. I was drawn to the place, the people, and the truth that was being covered up or denied.”

Over the course of five years, Machado, in a gesture to document the perpetual cycles of violence in Sri Lanka, visited the northern areas of laffna and Mullivaikkal. Afterlife VII, Mullivaikkal (2014), taken on the shore where, in 2009, the horrific final stand of the war took place, depicts a tangle of washed-up, shredded clothing. The remains of destroyed lives act as evidence for the silencing of fact and for a minority’s (in this case, the Tamil Hindu community) inability to grieve their dead and lay the past to rest.

Artist Abdul Halik Azeez is based in Colombo, Sri Lanka’s capital. His photographic essay Religious Intolerance and Islamophobia in Post-war Sri Lanka (2014-15) looks at the convenient twisting of truths. Made six months after the 2014 ethnoreligious riots in the southern town of Aluthgama, Azeez’s images capture moments in which sacred light is juxtaposed with petrol bombs, fake news on social media is set against the reality of peaceful coexistence, and a man in a white thole holds a sign reading HAMBAYA—an anti-Muslim slur. When making this work about unrest and misconceptions, Azeez says that he asked himself: “Was this what luly 1983 felt like?”

Azeez’s searching question echoes the sentiments expressed by some writers reporting on the recent Kandy incident. In each episode of violence, from precolonial to postwar, the misuse of cultural symbols is often the work of a few rather than the sentiment of the many. Unfolding these collective distortions, Perera, Machado, and Azeez choose to pursue faith, meaning, and poetry instead, and inadvertently discover truths about themselves. “My work is not only about photography, it’s also about self-discovery and finding meaning in my existence,” says Azeez. “There’s a Sufi saying that if you know yourself, then you know God.... There’s so much power in the way we think.”

Jyoti Dhar is an art critic based between New Delhi and Colombo.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsDiana Markosian Santa Barbara

Winter 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

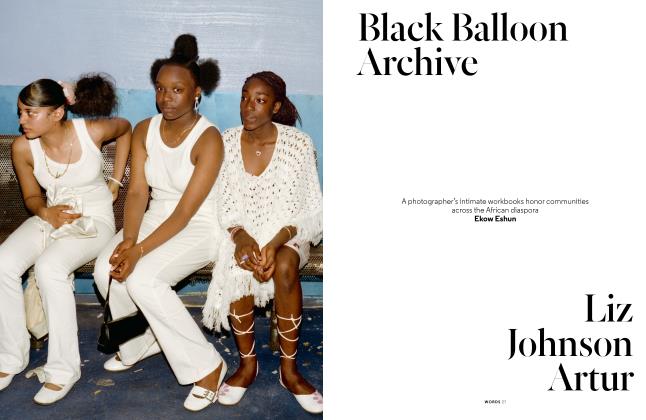

WordsBlack Balloon Archive Liz Johnson Artur

Winter 2018 By Ekow Eshun -

Pictures

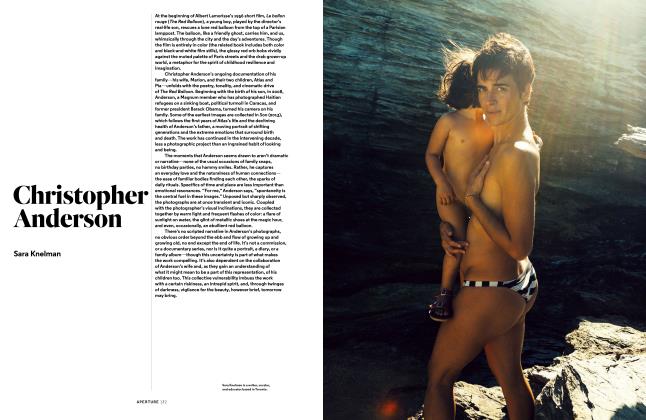

PicturesChristopher Anderson

Winter 2018 By Sara Knelman -

Words

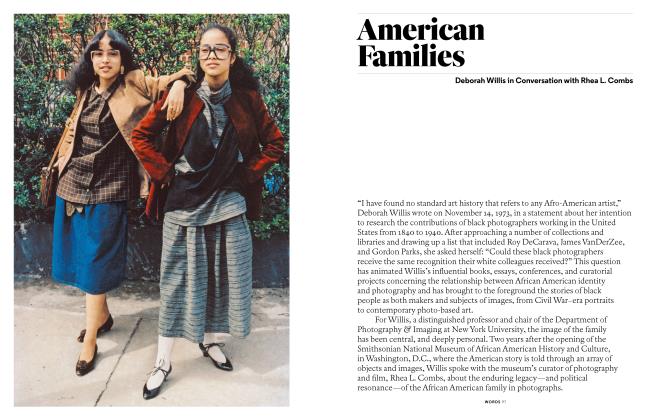

WordsAmerican Families

Winter 2018 -

Words

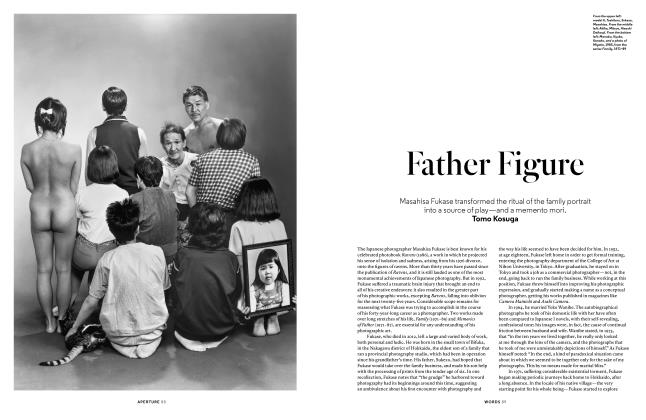

WordsFather Figure

Winter 2018 By Tomo Kosuga -

Pictures

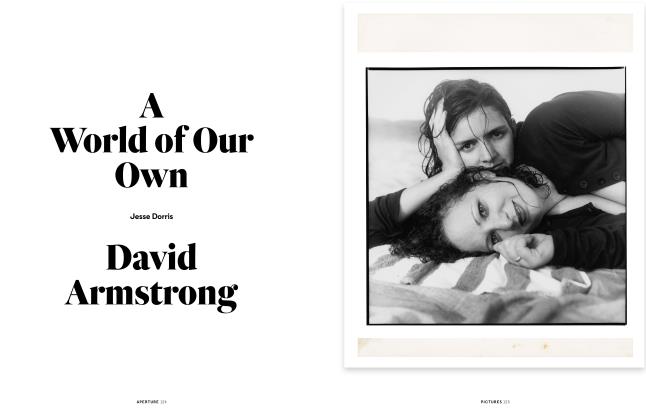

PicturesA World Of Our Own David Armstrong

Winter 2018 By Jesse Dorris

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jyoti Dhar

Dispatches

-

Dispatches

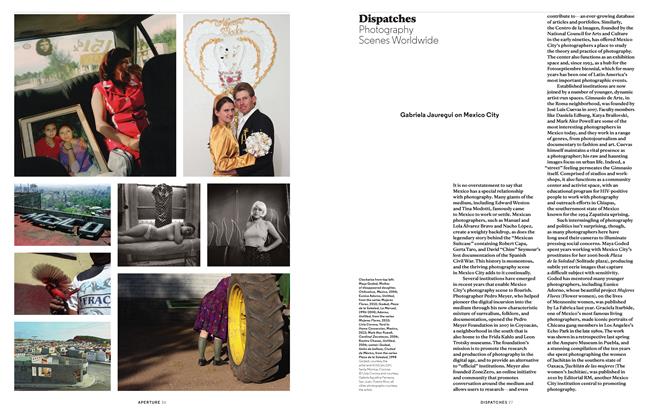

DispatchesGabriela Jauregui On Mexico City

Winter 2013 By Gabriela Jauregui -

Dispatches

DispatchesTehran

Spring 2018 By Haleh Anvari -

Dispatches

DispatchesCairo

Fall 2016 By Ismail Fayed -

Dispatches

DispatchesJason Fulford On San Francisco

Spring 2013 By Jason Fulford -

Dispatches

DispatchesIstanbul

Spring 2017 By Kaya Genç -

Dispatches

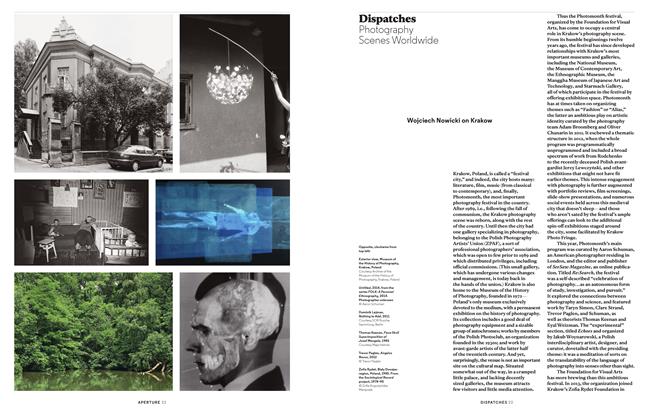

DispatchesWojciech Nowicki On Krakow

Winter 2014 By Wojciech Nowicki