Rodrigo Valenzuela

Matthew Schum

In General Song, his solo exhibition at Klowden Mann Gallery in Culver City earlier this year—the title is a nod to Pablo Neruda— Rodrigo Valenzuela amplified the photographs in his series Barricades (2017) with a departure, a dramatic sculptural installation of a riot barricade. This new work productively harangued about the politics of exhibition and created a physical imposition, as all effective installation art does, that had been missing from Valenzuela’s previous series. This sculptural turn took the primary subject of his primary medium, photography, and accentuated its rebellious energy.

Valenzuela is a fine arts professor of photography at the UCLA School of the Arts and Architecture, who replaced renowned postconceptualist James Welling. This impressive ascent began in 2005, when Valenzuela traveled from Chile and crossed, undocumented, into the United States. Barricades and his new series Masks (2018) trace a journey through the dictatorial shadow of Pinochet and take special inspiration from Neruda.

For Masks, Valenzuela re-created profiles of crafty protesters on the streets of Santiago who use plastic bottles and duct tape to make improvised tear gas masks. Using simple devices of dissent,

the DIY respirators reframe the human body and its visage. In Valenzuela’s images, each special design overwhelms the face (actually the artist incognito). His protesters are not only humans, they also resemble alien creatures, transformed by single-serving plastic containers. Insectile features radiate from a painted darkness Valenzuela designs in his studio down to the last pigment. As Valenzuela tells the story of these brave protesters in Chile, it is clear he envisions their actual struggle with empathy. These are not the dispossessed and disenfranchised masses found in newspapers, but architects of another world unsatisfied with this one.

Masks was inspired by Canto General, the collection of poems that established Neruda as an international literary figure.

I can hear the internal monologue of both Valenzuela’s protester and Neruda’s protagonist in the fourth canto of "The Heights of Macchu Picchu” (1947), from Canto General, in these lines:

Mighty death invited me many times: it was like the invisible salt in the waves, and what its invisible taste disseminated was like halves of sinking and rising or vast structures of wind and glacier.

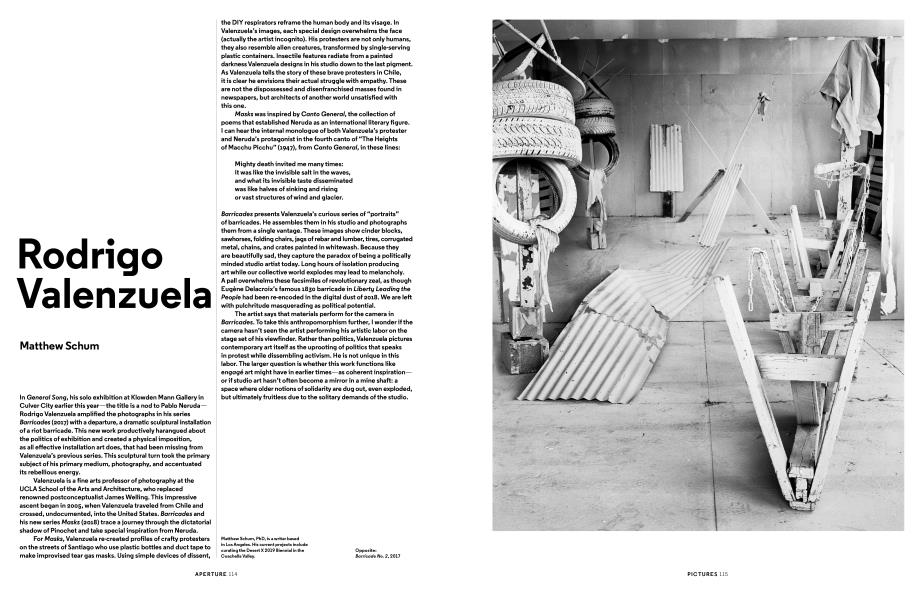

Barricades presents Valenzuela’s curious series of "portraits” of barricades. He assembles them in his studio and photographs them from a single vantage. These images show cinder blocks, sawhorses, folding chairs, jags of rebar and lumber, tires, corrugated metal, chains, and crates painted in whitewash. Because they are beautifully sad, they capture the paradox of being a politically minded studio artist today. Long hours of isolation producing art while our collective world explodes may lead to melancholy.

A pall overwhelms these facsimiles of revolutionary zeal, as though Eugene Delacroix’s famous 1830 barricade in Liberty Leading the People had been re-encoded in the digital dust of 2018. We are left with pulchritude masquerading as political potential.

The artist says that materials perform for the camera in Barricades. To take this anthropomorphism further, I wonder if the camera hasn’t seen the artist performing his artistic labor on the stage set of his viewfinder. Rather than politics, Valenzuela pictures contemporary art itself as the uprooting of politics that speaks in protest while dissembling activism. He is not unique in this labor. The larger question is whether this work functions like engage art might have in earlier times—as coherent inspiration— or if studio art hasn’t often become a mirror in a mine shaft: a space where older notions of solidarity are dug out, even exploded, but ultimately fruitless due to the solitary demands of the studio.

Matthew Schum, PhD, is a writer based in Los Angeles. His current projects include curating the Desert X 2019 Biennial in the Coachella Valley.

PICTURES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsJohn Divola & Mark Ruwedel

Fall 2018 By Amanda Maddox -

Pictures

PicturesTorbjørn Rødland: Into The Light

Fall 2018 By Travis Diehl -

Words

WordsIlene Segalove’s Modern America

Fall 2018 By Charlotte Cotton -

Words

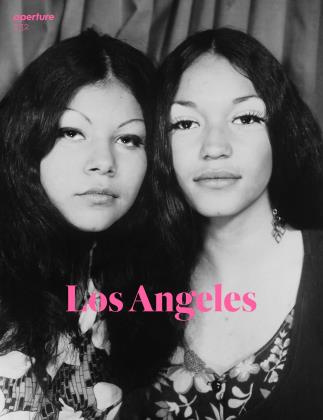

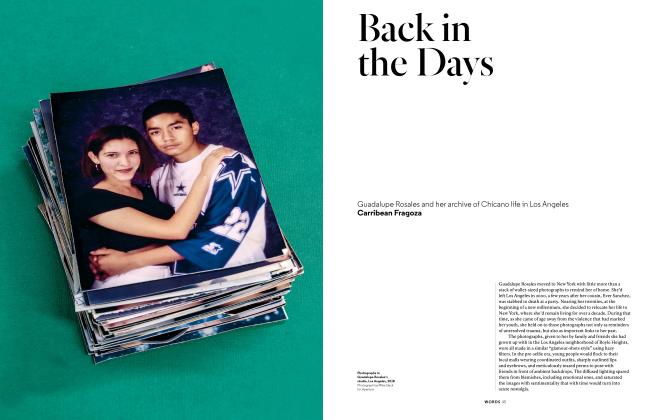

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Pictures

PicturesPaul Mpagi Sepuya

Fall 2018 By Andy Campbell -

Pictures

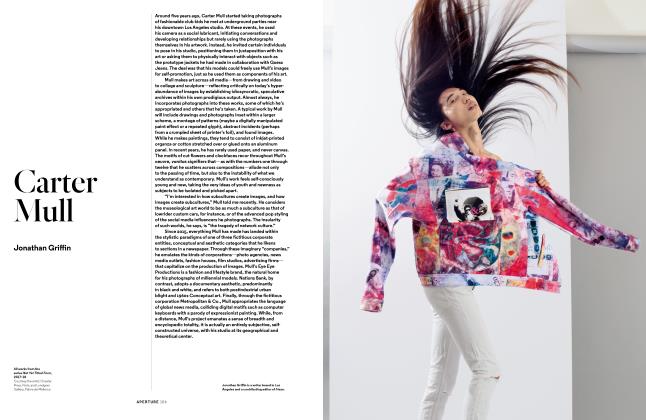

PicturesCarter Mull

Fall 2018 By Jonathan Griffin

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Pictures

-

Pictures

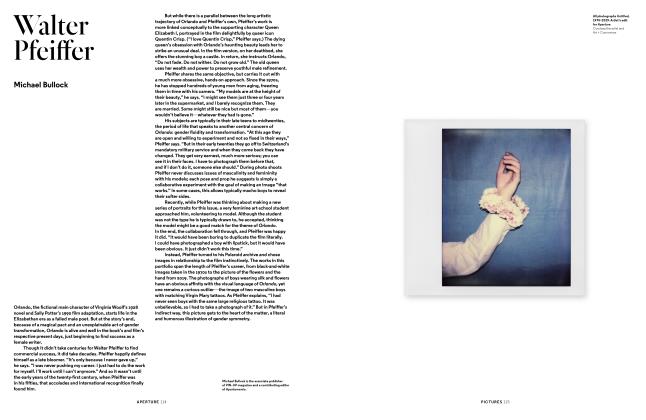

PicturesWalter Pfeiffer

Summer 2019 -

Pictures

PicturesZackary Drucker

Summer 2019 -

Pictures

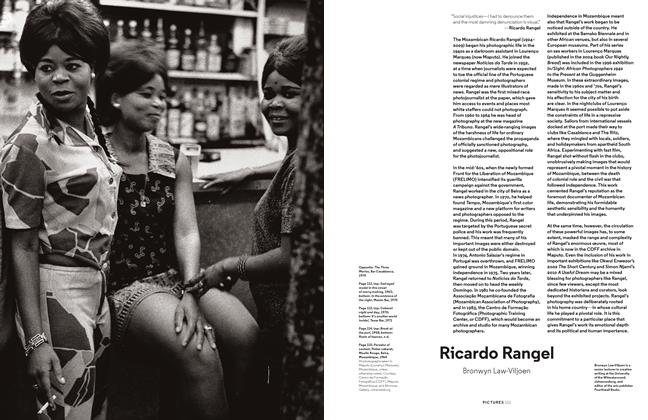

PicturesRicardo Rangel

Winter 2013 By Bronwyn Law-Viljoen -

Pictures

PicturesJames Mollison: Playgrounds

Fall 2013 By Chris Boot -

Pictures

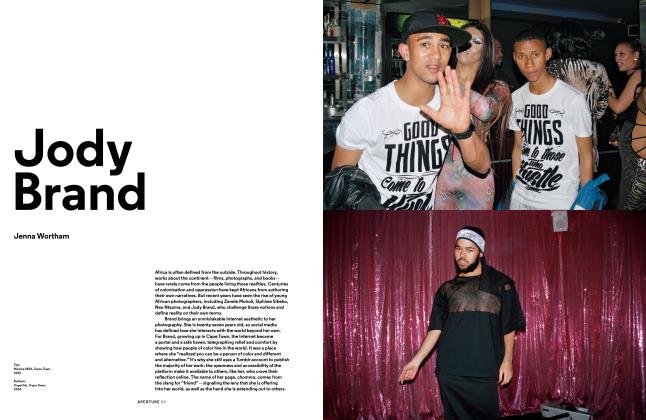

PicturesJody Brand

Summer 2017 By Jenna Wortham -

Pictures

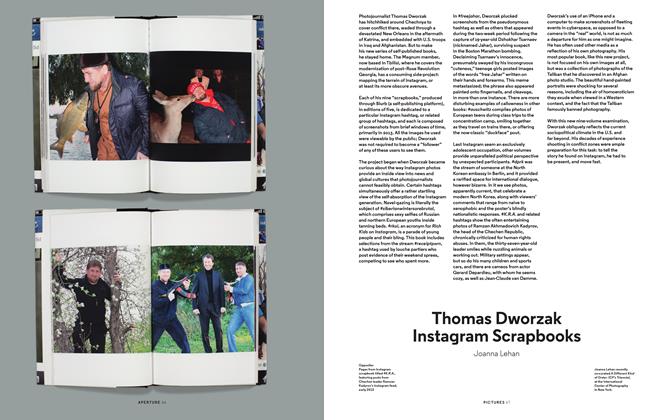

PicturesThomas Dworzak Instagram Scrapbooks

Spring 2014 By Joanna Lehan