Jack Lueders-Booth

Christie Thompson

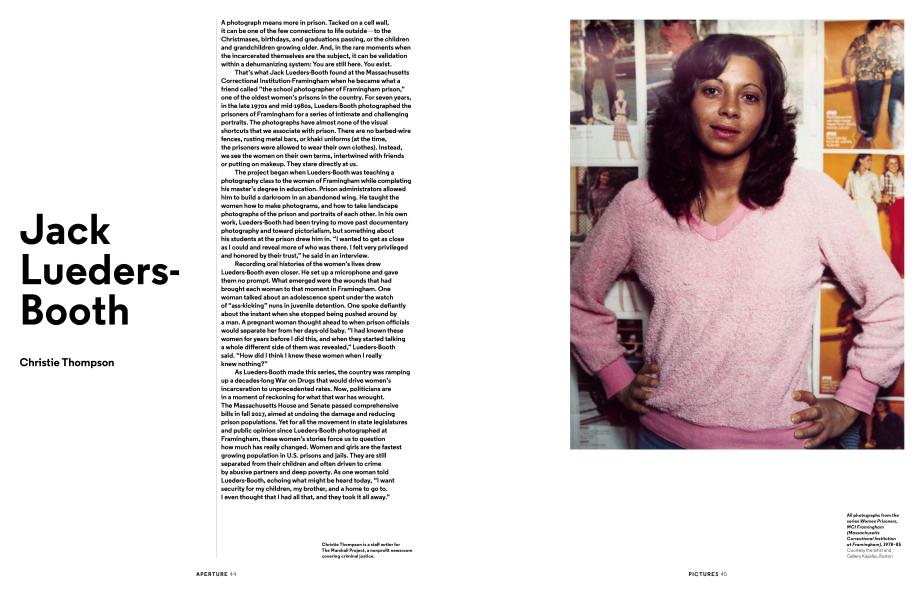

A photograph means more in prison. Tacked on a cell wall, it can be one of the few connections to life outside—to the Christmases, birthdays, and graduations passing, or the children and grandchildren growing older. And, in the rare moments when the incarcerated themselves are the subject, it can be validation within a dehumanizing system: You are still here. You exist.

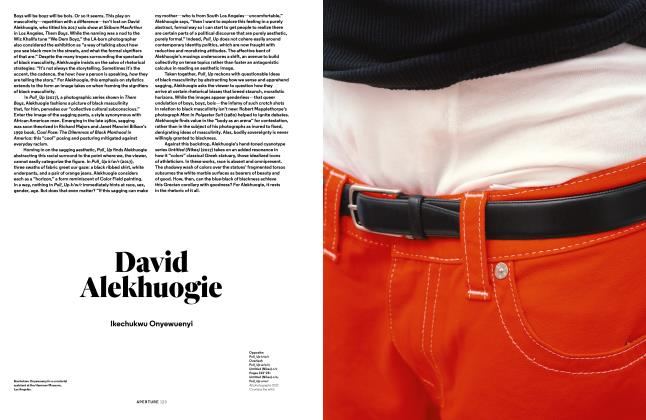

That’s what Jack Lueders-Booth found at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution-Framingham when he became what a friend called "the school photographer of Framingham prison,” one of the oldest women’s prisons in the country. For seven years, in the late 1970s and mid-1980s, Lueders-Booth photographed the prisoners of Framingham for a series of intimate and challenging portraits. The photographs have almost none of the visual shortcuts that we associate with prison. There are no barbed-wire fences, rusting metal bars, or khaki uniforms (at the time, the prisoners were allowed to wear their own clothes). Instead, we see the women on their own terms, intertwined with friends or putting on makeup. They stare directly at us.

The project began when Lueders-Booth was teaching a photography class to the women of Framingham while completing his master’s degree in education. Prison administrators allowed him to build a darkroom in an abandoned wing. He taught the women howto make photograms, and howto take landscape photographs of the prison and portraits of each other. In his own work, Lueders-Booth had been trying to move past documentary photography and toward pictorialism, but something about his students at the prison drew him in. "I wanted to get as close as I could and reveal more of who was there. I felt very privileged and honored by their trust,” he said in an interview.

Recording oral histories of the women’s lives drew Lueders-Booth even closer. He set up a microphone and gave them no prompt. What emerged were the wounds that had brought each woman to that moment in Framingham. One woman talked about an adolescence spent under the watch of "ass-kicking” nuns in juvenile detention. One spoke defiantly about the instant when she stopped being pushed around by a man. A pregnant woman thought ahead to when prison officials would separate her from her days-old baby. "I had known these women for years before I did this, and when they started talking a whole different side of them was revealed,” Lueders-Booth said. "How did I think I knew these women when I really knew nothing?”

As Lueders-Booth made this series, the country was ramping up a decades-long War on Drugs that would drive women’s incarceration to unprecedented rates. Now, politicians are in a moment of reckoning for what that war has wrought.

The Massachusetts House and Senate passed comprehensive bills in fall 2017, aimed at undoing the damage and reducing prison populations. Yet for all the movement in state legislatures and public opinion since Lueders-Booth photographed at Framingham, these women’s stories force us to question how much has really changed. Women and girls are the fastest growing population in U.S. prisons and jails. They are still separated from their children and often driven to crime by abusive partners and deep poverty. As one woman told Lueders-Booth, echoing what might be heard today, "I want security for my children, my brother, and a home to go to.

I even thought that I had all that, and they took it all away.”

Christie Thompson is a staff writer for The Marshall Project, a nonprofit newsroom covering criminal justice.

PICTURES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

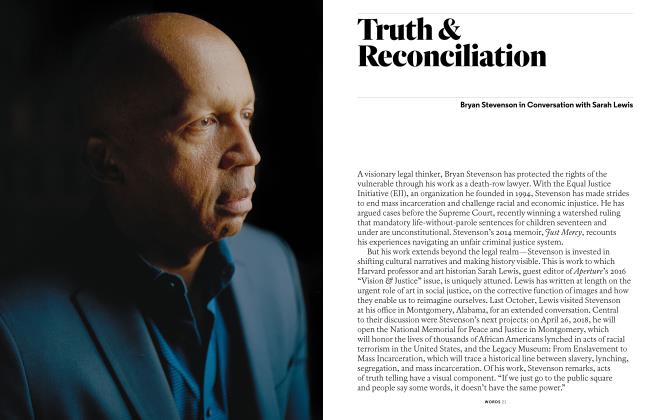

WordsTruth & Reconciliation

Spring 2018 By Sarah Lewis -

Words

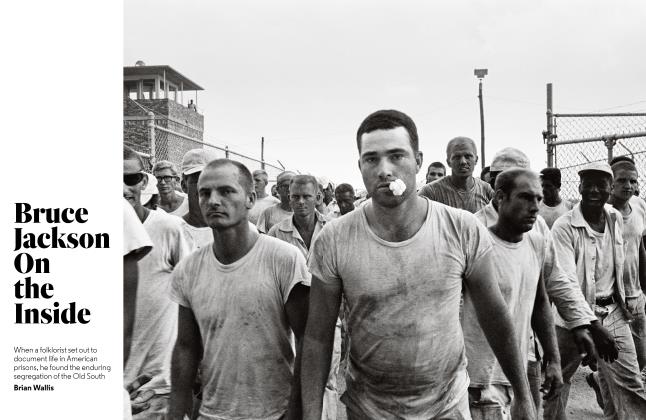

WordsBruce Jackson On The Inside

Spring 2018 By Brian Wallis -

Pictures

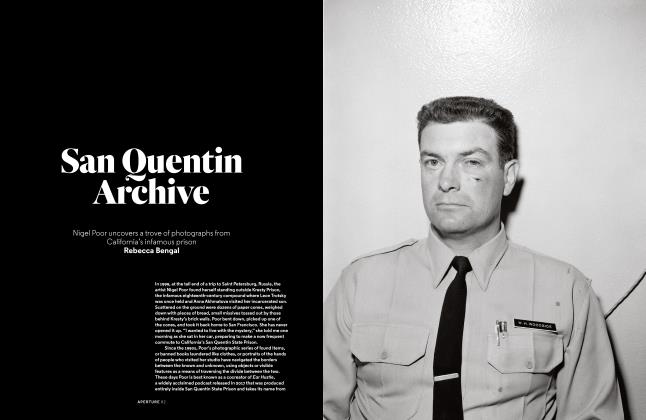

PicturesSan Quentin Archive

Spring 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Pictures

PicturesDeborah Luster

Spring 2018 By Zachary Lazar -

Pictures

PicturesStephen Tourlentes

Spring 2018 By Mabel O. Wilson -

Pictures

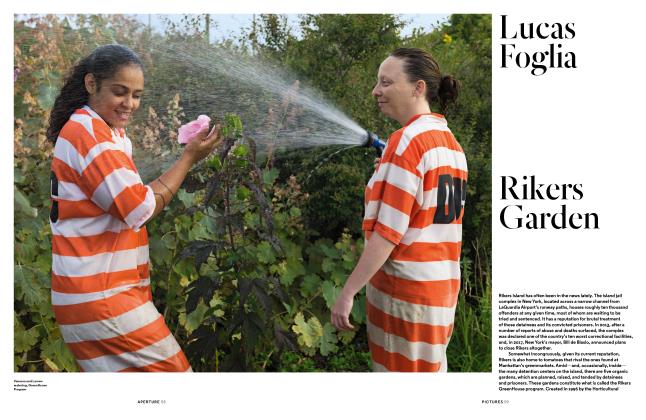

PicturesLucas Foglia

Spring 2018 By Jordan Kisner