Gus Van Sant A Thousand Compositions

Jonathan Griffin

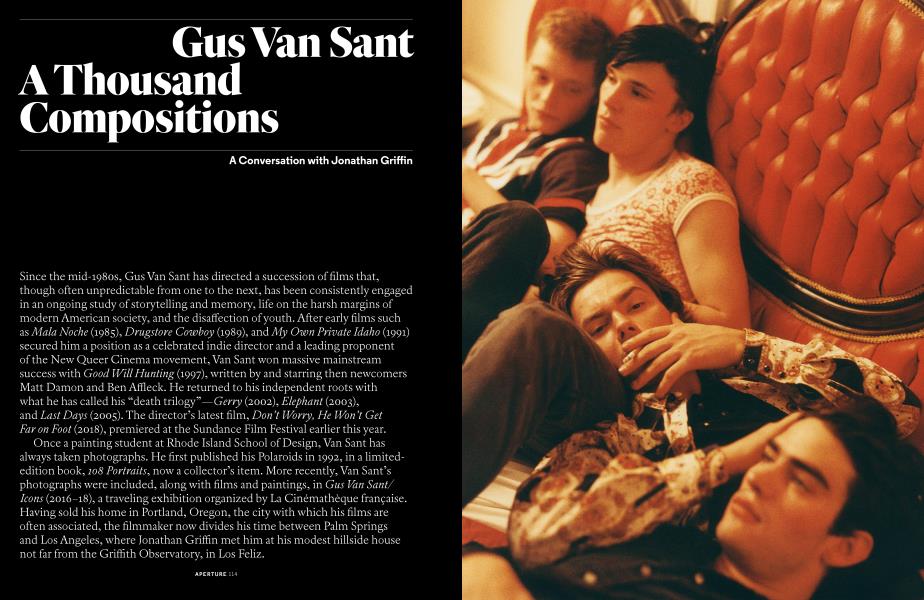

Since the mid-1980s, Gus Van Sant has directed a succession of films that, though often unpredictable from one to the next, has been consistently engaged in an ongoing study of storytelling and memory, life on the harsh margins of modern American society, and the disaffection of youth. After early films such as Mala Noche (1985), Drugstore Cowboy (1989), and My Own Private Idaho (1991) secured him a position as a celebrated indie director and a leading proponent of the New Queer Cinema movement, Van Sant won massive mainstream success with Good Will Hunting (1997), written by and starring then newcomers Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. He returned to his independent roots with what he has called his “death trilogy”—Gerry (2002), Elephant (2003), and Last Days (2005). The director’s latest film, Don⅛ Worry, He Wont Get Far on Foot (2018), premiered at the Sundance Film Festival earlier this year.

Once a painting student at Rhode Island School of Design, Van Sant has always taken photographs. He first published his Polaroids in 1992, in a limitededition book, 108 Portraits, now a collector’s item. More recently, Van Sant’s photographs were included, along with films and paintings, in Gus Van Sant/ Icons (2016-18), a traveling exhibition organized by La Cinematheque franfaise. Having sold his home in Portland, Oregon, the city with which his films are often associated, the filmmaker now divides his time between Palm Springs and Los Angeles, where Jonathan Griffin met him at his modest hillside house not far from the Griffith Observatory, in Los Feliz.

WORDS

Jonathan Griffin: Well before your directorial debut, in 1985, with Mala Noche, you were making photographs. Tell me about the customized Polaroid camera that you started using in the 1970s.

Gus Van Sant: It was for sale here in LA. It was based on a ’60s camera that used roll Polaroid film, which was actually quite heavy, so a company called Four Star somehow chopped the back off, and glued on a more modern plastic film holder that took film in a pack. There was one model that had a Rodenstock lens, with professional settings. That’s what everyone had if they bought this camera.

They were relatively common; I think photographers used them in the ’60s to check exposures. You can see Kubrick taking pictures with one on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)—to check lighting, I guess. They also made a type of film that included a negative within the Polaroid film. You had to wash out the paper, and inside the paper was this negative.

JG: Did you use the negative to reprint the pictures?

GVS: Yes, to make enlargements. As I was meeting actors, I needed the Polaroids to cast the movie, so I put them together to see whether the cast had a kind of chemistry in the photographs.

There was no Internet. The kinds of actors that I brought in didn’t have headshots. You had to take a picture of them to remember what they looked like. People used SX-70 cameras to do what I was doing, but I was using an older technology. Then I started using the negative film in case I ever wanted to do a show of the photographs.

JG: So you were taking photography seriously?

GVS: No. I was using it for the casting. I wasn’t taking photographs as a portrait photographer so much.

JG: But you were representing these actors in a particular way. These are beyond what a typical headshot would be.

They have atmosphere. They have thoughtful composition. There’s a sense of the person’s presence.

GVS: That was all a result of my limited setup. If you were the actor,

I would have you stand by the window, where the light was coming in, and I would take one picture. I would just go chhht, and you’d get out of here. I wasn’t posing them. They all have the same look, and I’m not sure why. I think it’s because we just had a fifteen-minute meeting where we were talking about something completely different, and all of a sudden, I said, “Okay, great—can I take a picture?”

JG: When you take a picture of an actor, are they inevitably in character?

GVS: Yeah, they are. A lot of times they read from the script, and they were wearing things that could possibly be in the film.

JG: How often did they turn out to be exhibition quality?

GVS: Exhibition quality? Well, I used all of them! I’ve never rejected one of the shots because something went wrong. Some of them have aberrations. It was always natural light from the side. I needed the natural light to expose 50 ASA film. It was usually all the way open, and it was around one-fifteenth of a second. It was on the edge of becoming blurry. The depth of field is at its minimum, so the background is sometimes quite soft, which is nice. And then, sometimes, there’s a little bit of a double exposure because they’ve moved slightly, or I’ve moved the camera. So there is this dicey, nonfinished aspect to them.

JG: You tend not to use artificial light in your films. Was that something you were thinking about at this time?

GVS: Yes. Once you turn a light on, then you have to use other lights to augment it, and you’re basically trying to make it look natural, so you might as well just go with whatever the natural is. In the past, film was slow enough that you kind of had to light, and then film became faster.

JG: Are simplicity, directness, and honesty principles that you aim for throughout your work?

GVS: Yeah, it’s an attempt at that. Sometimes it was just out of necessity. I didn’t have the lights, or money for lights—or for very many lights. Like on Mala Noche, which was shot on very slow film—50 ASA. It was Kodak Plus-X 16mm. I was, again, sort of riding the edge of exposure with my first movie. It has a similar quality to the Polaroids because we’re using natural light in situations where you’d normally use bigger lights. It gave it a kind of dark quality.

The reversal film made it very sumptuous, the kind of black-andwhite image that you see in Warhol’s ’60s movies, because he’s using the same Plus-X film. He was probably using reversal because then you don’t have to make a print. You just watch the original. That’s why I did it, too.

JG: For immediacy?

GVS: For Warhol, it might have been immediacy. It probably wasn’t a cost issue for him. For me, it was definitely a cost issue, that I could watch my dailies without printing them, and I could edit out the bad parts and only print the stuffl wanted to use.

JG: Were you doing your own photography on Mala Noche?

GVS: No, but I was lighting it. I had a DP. But I was basically deciding what lights to use. The DP had a box of lights. I had rented these spotlights from a theatrical lighting company that were very weak— but they were spotlights.

JG: Was the effect that you got completely intentional, or were you finding your way as best you could with the resources you had at the time?

GVS: Both. It was intentional, but I was finding my way too. Both the Polaroid and Plus-X reversal have kind of amazing qualities, a magic that I knew about, that I had seen in other films I had made. So I was relying on the quality of the actual film to sort of give it a certain look.

And we were using locations that, in Mala Noche, at least, were very real, because they were mostly free. They were places like the original author’s apartment, which was perfectly art directed because it was the real thing.

JG: You were effectively using Dogme principles?

GVS: It’s sort of what Dogme was up to. They’re using the rules of a no-budget film. In Elephant we were using a high school that had been evacuated because of a scare of mold. The extras were high school students from all over Portland. None of them were actors; they wore their own clothes. So that was quite real.

JG: The separation between the persona and the actor seems paper-thin in so many of your films. When you were taking these photographs of actors, were you trying to picture them as themselves? Or is a photograph simply about the way that person could be ht into a particular him? Is there a difference between the real person and the person as a character?

Many things will happen within a shot. The composition is moving like a kaleidoscope.

GVS: I’m always trying to bring out a very realistic quality—whatever that is.

JG: A lot of people in your films are either actors you’ve worked with repeatedly or nonactors you know personally.

GVS: It depends on the film. In Elephant, the high school students were in situations where they normally would be during the day, and they said the things that they would normally say. In To Die For (1995), they were all professional actors playing written roles.

JG: And then there’s someone like Matt Damon, who you’ve worked with repeatedly.

GVS: Yeah, except by the time we got to make Good Will Hunting, Matt and Ben [Affleck] had been working on that script for almost six years. Six years of improvising a script. So whatever they did was more like improvisation.

JG: And in Gerry, Damon is wearing his own clothes, and improvising dialogue with an actor, Casey Affleck, who is his friend on-screen as well as off.

GVS: We had created scenes together where they were improvising, and by the time we got on the set, they were continuing to improvise. All three of those movies—Gerry, Elephant, and Last Days—were based on a mystery around what had happened in an actual event, and also unavailable or undependable witnesses. In the case of Gerry, the story came from the only survivor. He was not dependable, because he could have been making it up. In Elephant, it was a huge preoccupation of many journalists to figure out what had happened at Columbine, and they’re still investigating it today.

JG: It’s unknowable.

GVS: All three of them are kind of unknowable. Last Days was about the missing three days of Kurt Cobain’s life, before he was found dead.

JG: How do you navigate this idea of truth when on the one hand the films project this feeling of honesty, a kind of verite realism, but at the same time, they are almost complete fabrications, as there is so much that is unknown within the source stories?

GVS: Well, all three of them have these gaps in the truth, so you needed to make things up or else you couldn’t figure out what they had done.

JG: You’ve talked in the past about different filmmakers who’ve influenced you, and you just mentioned Warhol.

But are there artists or still photographers who have been important for your films?

GVS: William Eggleston and Frederick Wiseman. Also D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock and a lot of the guys who worked in cinema verite of the ’50s and ’60s, which was generally black and white.

JG: Why Eggleston?

GVS: Eggleston was shooting people who were generally not posing. He’s usually in the world somewhere, not under a controlled situation. There is a documentary quality to it. But also, I just liked the quality of the photographs.

JG: Do you take photographs now?

GVS: Yes, but it’s not a daily thing.

JG: You say in your recent book Gus Van Sant: Icons (2016) that movie making isn’t so much to do with composition and still photography is.

GVS: I think so.

JG: Really? When I watch your films every shot seems so thoughtfully composed.

GVS: Well, you’re kind of composing it, but you’re also composing for something that’s going to move around. So the composition is not going to be frozen, it’s going to tilt up and down and right and left. Many things will happen within a shot. The composition is moving like a kaleidoscope, like a thousand compositions.

J G: When you talk about composition in that sense, you’re talking about framing, really. You’re talking about the edges of the frame.

GVS: Isn’t that what composition is?

JG: Well, it may be moving around within the frame, but it’s still an internal composition.

GVS: I don’t think you’d call it “composition.” I think you’d call it an “event.”

JG: I’m curious what involvement, if any, you have in the creation of stills from your films that get used for publicity?

GVS: Well, sometimes stills are taken literally from the film. They stop the film on a frame and print it. I’m not in control of that. Sometimes, they’ve selected film stills that a photographer has taken on the set. Which I’m also not particularly involved in.

JG: Does that ever bother you?

GVS: No. It used to bother me a little bit, because I always thought, Why don’t you take images from the actual film? With the film camera, everything is moving and there’s never a very in-focus frame. The still photographer is there because he can take lots of different pictures that are crisp and clear. I kind of like it now, depending on who’s taking the photographs.

JG: In your recent exhibition, Gus Van Sant/Icons, there were a number of your hand-drawn storyboards. When you make these storyboards, you’re making compositions.

GVS: Yeah. But as you see, there are arrows, and there are curlicues. I’m trying to map out the action.

JG: Rather than pin down particular images.

GVS: It’s not really about the composition.

JG: In those early storyboards, you’d glue on Polaroid photographs that you’d taken on set.

GVS: That’s true. The Polaroid was more to know that I did that shot. But I stopped doing it. It took too long to wait for the Polaroid to process. It also was expensive to use Polaroids for every shot. But at first, I was very meticulous. A lot of times I’d use the Polaroid to check the lighting, to see what the lighting was going to look like.

JG: So when you were taking those photographs, you weren’t comparing your mental image of the shot, or the drawing, with what actually came out?

GVS: No. Because it was all so hypothetical. The storyboards in the exhibition are all from Mala Noche, I think. Those were me sitting in Connecticut in my bedroom, while I was saving up money to afford to make the movie.

JG: What project are you working on now?

GVS: It’s called Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot. It’s about a quadriplegic cartoonist who’s an alcoholic. It’s based on the life of John Callahan, a Portland guy, a contemporary of the main character in Mala Noche, Walt Curtis.

JG: Where was his stuff published?

GVS: In weeklies like the Village Voice, or the LA Weekly, or, in Portland, it was the Willamette Week. Later, he wrote a book— also titled Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot (1990)—after he had made his way as a cartoonist. The book was bought by Robin Williams. That’s how I got involved, in the mid-’90s. Even though I’m from Portland and I knew John Callahan, I’d never read his book.

JG: You knew him personally?

GVS: I’d met him. I didn’t know him well. We adapted the book for Robin. Then Robin died in 2014. The project was still at Sony, the book was at Sony, and they called and said, “Are you still wanting to do this?” So it’s a very old project.

JG: Who ended up playing the role?

GVS: Joaquin Phoenix.

JG: Whom you’ve worked with before.

GVS: Only once, in To Die For. But I’ve known him all these years.

JG: Your back catalog is so varied. Is there a particular film that you feel it’s akin to?

GVS: It’s like Good Will Hunting and Mala Noche, and it’s a little bit like Finding Forrester (2000). Those three. The Mala Noche part is that it’s a kind of out-of-the-way Portland story about a dispossessed character. Then, as with Good Will Hunting and Finding Forrester, it’s describing his journey in getting better from alcoholism, so there’s a learning thing. In Good Will Hunting, the main character’s learning about his past, learning that it’s not his fault.

In Finding Forrester, the character is learning to write—and our character is learning to cartoon.

JG: Is it going to be successful?

GVS: We’ll see. I think we got lucky with Good Will Hunting.

Jonathan Griffin is a writer based in Los Angeles and a contributing editor of frieze.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

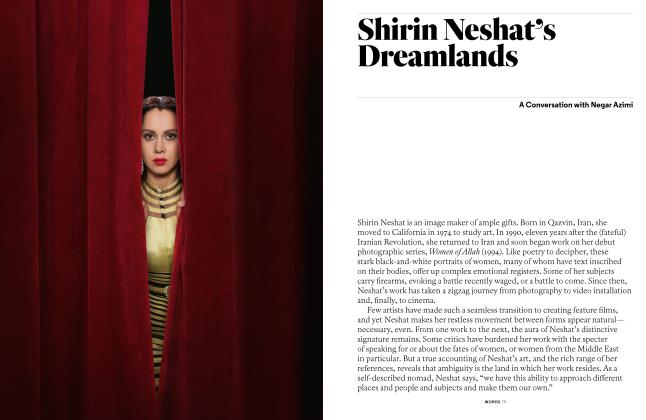

WordsShirin Neshat’s Dreamlands

Summer 2018 By Negar Azimi -

Words

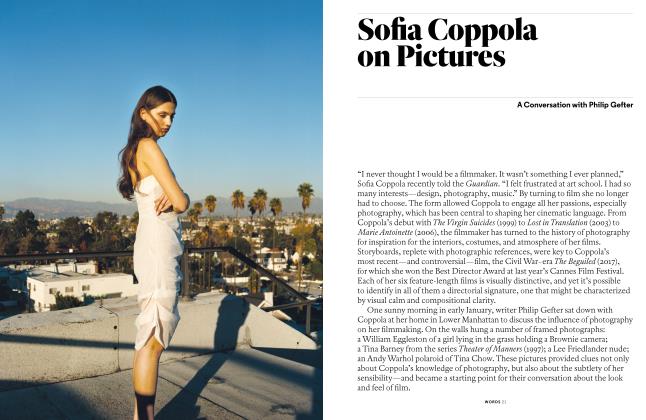

WordsSofia Coppola On Pictures

Summer 2018 By Philip Gefter -

Pictures

PicturesAlex Prager

Summer 2018 By Rebecca Bengal -

Words

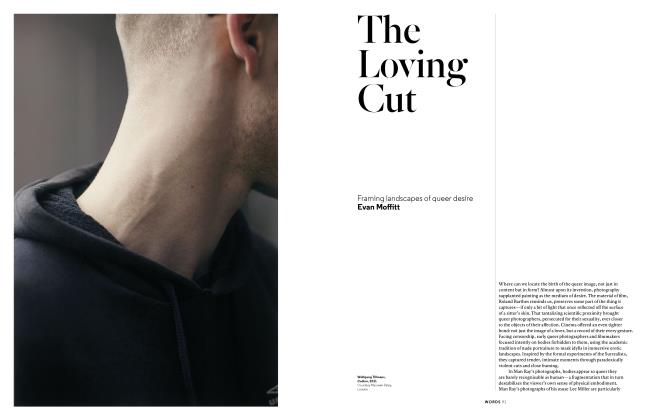

WordsThe Loving Cut

Summer 2018 By Evan Moffitt -

Words

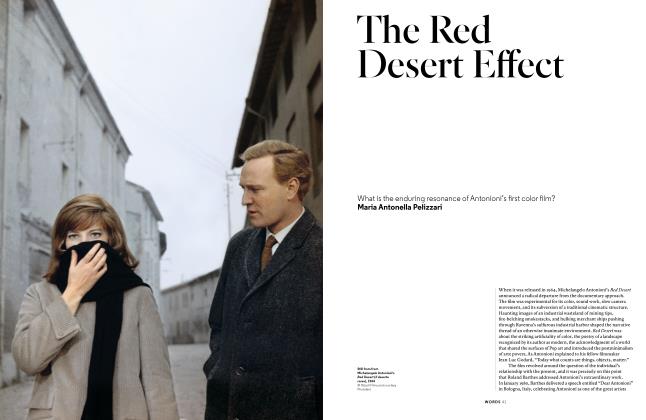

WordsThe Red Desert Effect

Summer 2018 By Maria Antonella Pelizzari -

Pictures

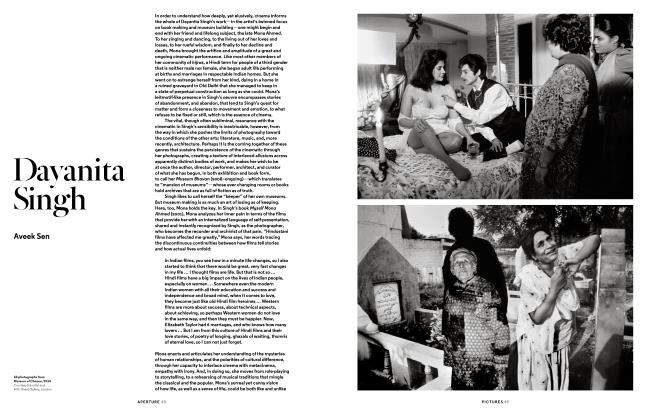

PicturesDayanita Singh

Summer 2018 By Aveek Sen

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jonathan Griffin

Words

-

Words

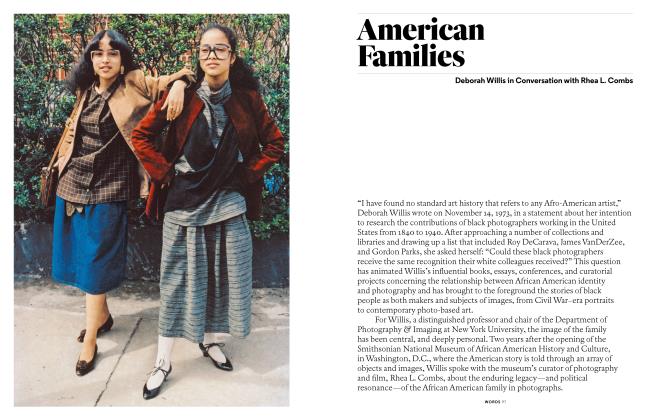

WordsAmerican Families

Winter 2018 -

Words

WordsMinimal, Messy, Or Melancholic?

Spring 2020 -

Words

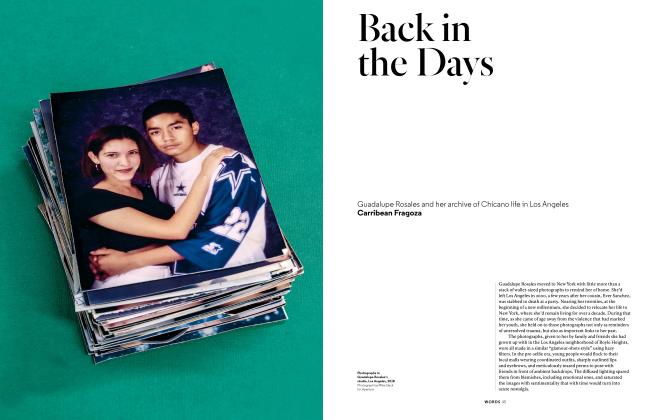

WordsBack In The Days

Fall 2018 By Carribean Fragoza -

Words

WordsThrough The Lens

Summer 2017 By Franziska Jenni -

Words

WordsThe Shadow And The Flash

Fall 2019 By Iñaki Bonillas -

Words

WordsRescripted

Winter 2014 By Matthew S. Witkovsky