THRESHOLDS OF A COMING COMMUNITY: PHOTOGRAPHY AND HUMAN RIGHTS

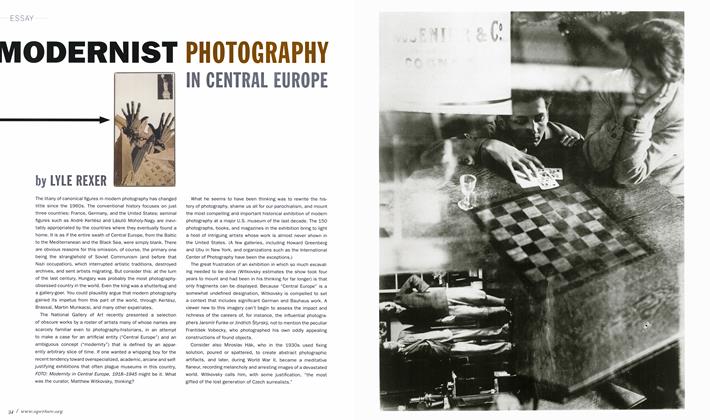

ESSAY

ANTHONY DOWNEY

The medium of photography has had an extended and probing relationship with issues surrounding human rights, migration, political violence, and the plight of refugees. As such, it is well suited to the exploration of a number of topics that are currently at the forefront of both political science and critical theory. The most prominent of these is the proposition that the refugee and the subject of oppression are not liminal figures that exist in a hinterland of invisibility; on the contrary, they are symbols of a “coming community” that is based upon exclusion. As emblems of otherness they are, in essence, far from being either other or indeed marginal. Photography as a medium, in all its immediacy, has the capacity to represent that reality—the vertiginous proximity of what it is to be a refugee, homeless, or oppressed.

To fully understand this proposition, and the role of photography in highlighting it, we need to turn to Hannah Arendt’s The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), a book that addresses, among other things, the quandary of the refugee and the subject who is without rights. Arendt’s argument points out a profound injustice, one that continues to haunt the discourse and application of human rights today: when an individual (such as a refugee) is deprived of nationstatehood and sociopolitical identity, the very rights that should protect him cannot do so. Human rights, then, are the rights of the citizen, not of the refugee, the homeless, the political prisoner, the migrant laborer, the dispossessed, the tortured, the silenced—all rightless individuals who are beyond recourse to the law and redress before it. What we find in Arendt’s book is the radical crisis at the heart of human rights today and the implicit shortcoming of modern democracy: the “rights of man" are a convenient fiction, in that they belong only to the citizen who is imbricated within a national, and therefore political, community.

With these points in mind, Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben has embarked upon a sustained critique of what he terms “bare life” (vita nuda)—a life that is without political representation (human rights) and thus borne in a legal no-man’s-land. In a body of work that has done much to address the contradictions that undermine the application of human rights, Agamben sees the refugee and the rightless not as liminal figures who test the parameters of national and international law, but rather as the “paradigm of a new historical consciousness.” They are, for Agamben, the vanguard of a “coming community” to which we could all one day belong.1 The disconcerting question at the heart of Agamben’s argument (which is even more chilling than Arendt’s) is this: What if the refugee, the political prisoner, the disappeared, the victim of torture, the dispossessed, and the silenced are not only constitutive of modernity but its emblematic subjects?

In order to come into being, those who endure “bare life,” those who exist without rights, must be consigned to what Agamben calls a “zone of irreducible indistinction.” It is within such zones, or on such thresholds, that legality and illegality are blurred, the rule of law is suspended, human rights are abrogated, and the distinction between citizen and non-citizen is rendered strategically, if not fatally, unclear.2 Such zones abound in our modern day: in refugee camps, along the contested borders of warring countries, in areas of civil strife, in the zones d’attentes and holding cells of national airports—all those nonsites where illegal migrants are temporarily parked by national authorities. Still more disturbing, of course, are the locations we do not see: the torture cells and prisons where countless individuals languish beyond the remit of international or national law.

As a form of documentation, photography occupies something of a privileged position in these discussions. Born in Paris and educated in Tangiers, Yto Barrada returned to the latter city in 1999 to photograph its inhabitants. What she found there was a people caught in a limbo-like state that had its roots in the extension of the Schengen Agreement in 1991, which made it easier for citizens of European states to travel across borders, but much harder for Moroccans wanting to travel to Spain. Those who have made the

journey across the Strait of Gibraltar illegally are referred to as the “burnt ones” because, in the act of burning their passports before departure, they have effectively waived their rights as citizens and all access thereafter to legal redress. Paradoxically, at the very moment of aspiring to a new life, these individuals have been reduced to “bare life.” Seeking a new form of subjectivity, they risk their lives—the word “burnt” can also refer to the many thousands who have died in the attempt to make the crossing—and must renounce their former existence and any form of subjectivity that it may have held for them. Departure and arrival become simultaneously a self-effacing act of selfdenial and a form of self-imposed exile, and yet also represent an attempt to reconfigure another self, another subjectivity.

Throughout Barrada’s images we see the sense of hopelessness, ennui, and isolation that converges upon the border and the interstitial space that is Tangiers. In her 2000 photograph Le Détroit (The strait) we see a boy with a toy boat, and an expanse of road, on the other side of which is a group of women. The metaphoric content of this photograph is easy enough to read—the road as the Strait of Gibraltar, the toy boat as a real boat. In other images, such as Ferris Wheel—M’dig (2001), we are presented with an allegory of confinement and an almost purgatorial repetitiousness. A Ferris wheel is in constant movement and yet goes nowhere. This has resonance when we consider the Moroccans and other Africans who are in constant movement in Tangiers but are also going nowhere. Barrada has observed: That state that I've described in my body of work creates a sort of floating figure . . these are the portraits that I am making, of people in the streets who are just waiting for their turn."3

Like most images of "zones of indistinction" and of "bare life," Barrada's photographs take an interrogatory stance with regard to human rights and social (in)justice.4 In this context, we may want to ask a further question: how effective are photographs when it comes to responding to the socioeconomic, political, ethical, and cultural demands of the milieu in which they are produced, disseminated, and exchanged? This is a question that could be posed in reference to the Palestinian-born photographer Ahlam Shibli's images of the Palestinian Bedouin of the Naqab. Displaced from their homelands since the 1960s to make way for Israeli settlements, the Bedouin of the Naqab have been consigned to live either in seven designated townships (home to more than 110,000 people in total) or in villages where the laws of the Israeli state effectively preclude any development or access to public services, such as education, healthcare, and sanitation.5 The life of the Bedouin of the Naqab is indeed "bare life"-that is, life pared down to the most meager essentials and beyond the reach of national or international law. In Shibli's images, home, territory, and statehood are all seen as provisional-mere tokens of a community that betray the absence of a political community.

This sense of the provisional, the improvisational, and the exigencies of living day-to-day in a war zone, emerges throughout Admas Habteslasie's series Limbo (2000-07), in which we see an entire population caught between war and peace in Eritrea, and thereafter shunted from one refugee camp to another. In one picture a makeshift tent leans precariously to one side, a sorrylooking bulwark against the shifting tides of Eritrea's ongoing civil war with Ethiopia. In another image a telecommunications building, shelled to the point of near-collapse, looks like a tired animal, its supporting pillars buckling beneath the weight of history and conflict. In Eritrea, which has been a de facto "zone of indistinction" for many years, we observe the ways in which human rights may be suspended within the various states of emergency that follow a declaration of war.

In a similar vein, Lebanese-based photographer Dalia Khamissy's images depict refugees stranded on the border of Jordan and Iraq during the summer and fall of 2004. These individuals exist along a stretch of land that is commonly referred to as "No Man's Land." It is worth recalling here Agamben's proposal that the refugee and the rightless augur inevitably imminent forms of community in which we may all one day play a part. "What is new in our time," Agamben argues, "is that growing sections of humankind are no longer representable inside the nation-state-and this novelty threatens the very foundations of the latter. Inasmuch as the refugee, an apparently marginal figure, unhinges the old trinity of state-nation territory, it deserves instead to be regarded as the central figure of our political history."6

To be a refugee, to be without rights, you do not necessarily have to leave or be expelled from a political community: you can live within a political and national community and still be apart from it. The homeless, the dispossessed, the marginalized in our midst all offer examples of lives endured with only the barest necessities, or indeed, with nothing at all. Malian photographer Sada Tangara explores such "internal exile" in his documentation of fellow countrymen (most no older than boys), as they eke out a precarious living on the streets of Dakar. These children, abandoned and without any community other than that which they can cobble together on the streets, huddle in doorways and in derelict cars trying to catch whatever sleep they can.

Although forsaken by their state and harassed by its laws, these children of Dakar are nevertheless-in the paradoxical visibility of their everyday invisibility-in a different category from those indi viduals who are "disappeared" by the state. In the ongoing politi cal tragedy that is modern-day Algeria-a country where a "state of emergency" is now the norm-more than six thousand individuals have been disappeared since the onset of civil war in 1992, many of them at the hands of the security forces. Algerian photographer Omar D. brings us pictures not only of the disappeared but of what they have left behind: their belongings, their empty rooms, grieving relatives who await their return, and, in these moments of despera tion, all the doubts and unanswered questions about the where abouts of the disappeared.7 One of the more common refrains from those relatives and friends is that they do not know whether their loved one is alive or dead. The disappeared have entered the most extreme "zone of indistinction," wherein citizenship can be blurred into a life of utter dispossession, and life itself into death.

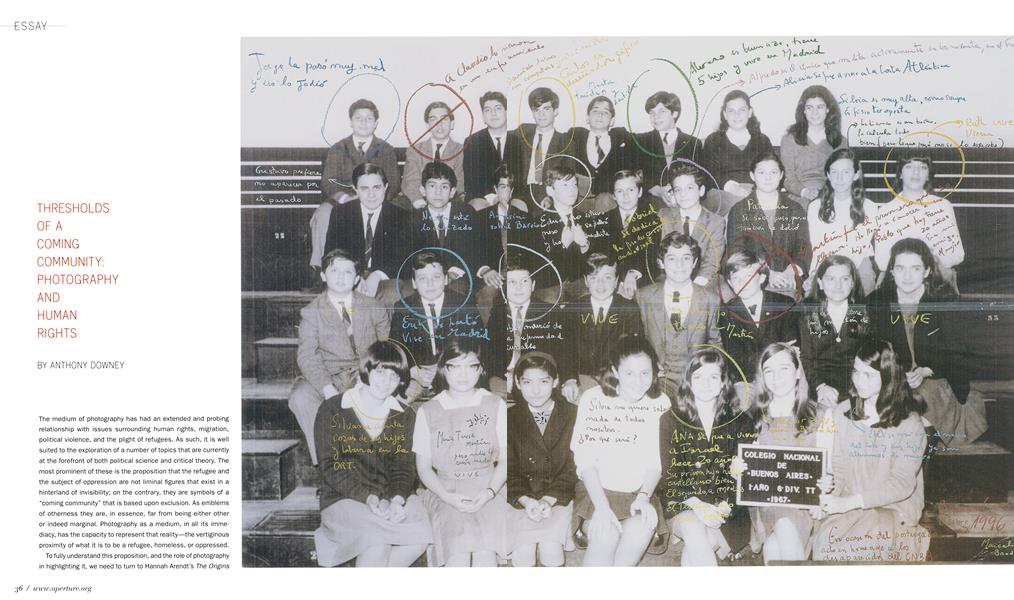

There is a depressing litany of countries where disappearances have been and continue to be part of everyday life. In the mid 1990s, the Argentinean photographer Marcelo Brodsky returned to his homeland equipped with a camera and a 1967 photograph of his eighth-grade class. For his project Buena Memoria: The Classmates (1996), Brodsky enlarged the photograph and annotated it, noting where each of his classmates had ended up. Some had married, others had gone into exile, and two members of the class had been disappeared. In this act of tapping into collective memory, Brodsky brings to the fore the role of photography in addressing what is now absent: the moment when that which no longer exists as anything but trauma can be represented visually. Here, a "zone of indistinction” is reified as something tangible, and revealed to us in all its guile.

The photographic practices outlined here have produced a realm within the sociocultural, historical, and political domain, a place of speculation into the ambivalent margins and dissonances that underlie modern life. In the context of the “zones of indistinction” posited by Agamben, such practices would seem to be well suited to the investigation of subjects—the refugee, the dispossessed, the political prisoner, the disappeared, the homeless, the victim of torture, the silenced—who are often ignored but are nevertheless increasingly prevalent in our time. The images on these pages haunt discourses on human rights and social (injustice. In such representations, finally, we may recognize the subject of “bare life” for what it is: a subject abandoned by modernity, but one that nonetheless exposes the potential relationship of all subjects to modern forms of power.©

NOTES

1 Giorgio Agamben, Means without End: Notes on Politics (1996; Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), p. 15.

2 Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Ufe (1995; Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1998), p. 9.

3 Barrada, in “Morocco Unbound: An Interview with Yto Barrada," by Charlotte Collins, see http://www.opendemocracy.net/arts-photography/barrada_3551. jsp (emphasis added).

4 I have written elsewhere on Yto Barrada’s Straits Project. See Anthony Downey, “A Life Full of Holes,” Third Text 20, no. 82 (2006): 617-26.

5 See Ulrich Loock, Documenta 12 (Cologne: Taschen, 2007), p. 154.

6 Agamben, Means without End, pp. 21-22.

7 See Omar D., Devoir de Mémoire/A Biography of Disappearance, Algeria 1992-, ed. Tom O’Mara (London: Autograph ABP, 2007).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

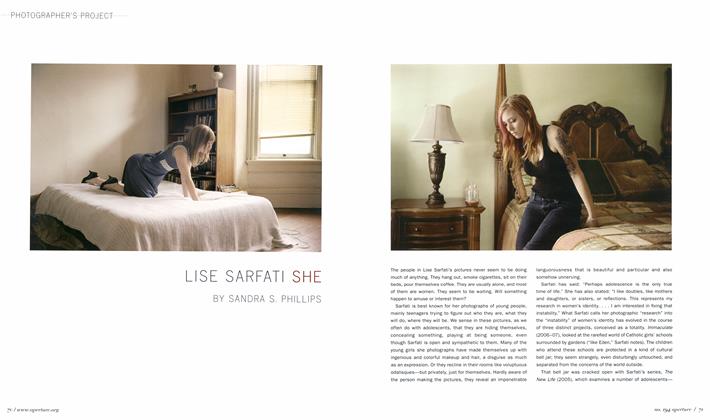

Photographer's Project

Photographer's ProjectLise Sarfati She

Spring 2009 By Sandra S. Phillips -

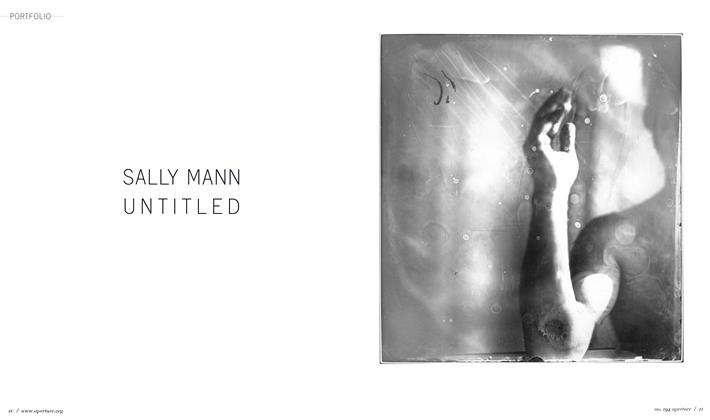

Portfolio

PortfolioSally Mann Untitled

Spring 2009 -

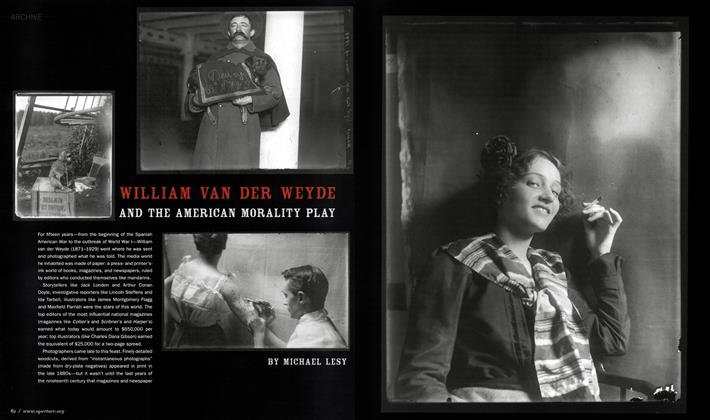

Archive

ArchiveWilliam Van Der Weyde And The American Morality Play

Spring 2009 By Michael Lesy -

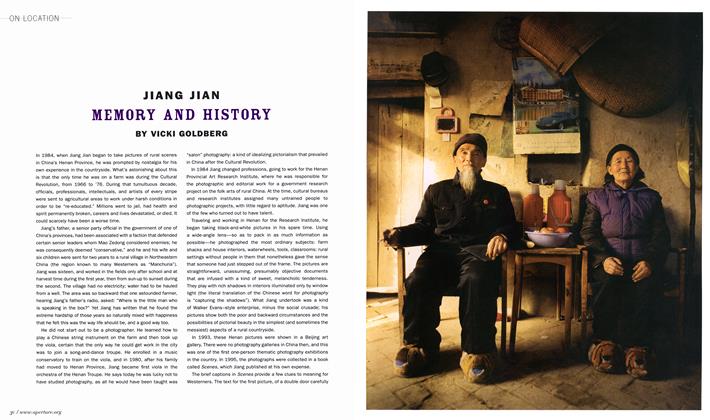

On Location

On LocationJiang Jian Memory And History

Spring 2009 By Vicki Goldberg -

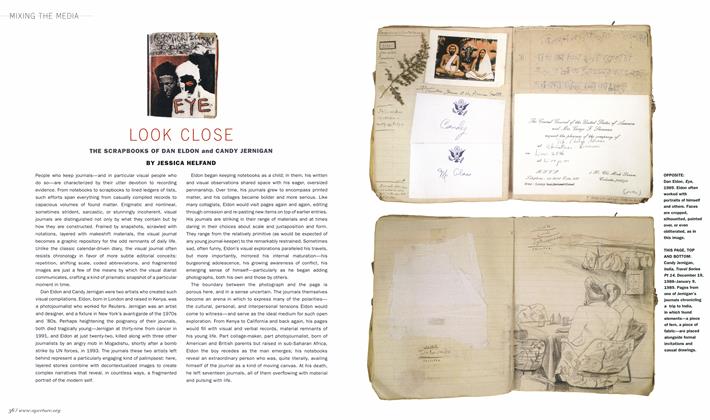

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaLook Close The Scrapbooks Of Dan Eldon And Candy Jernigan

Spring 2009 By Jessica Helfand -

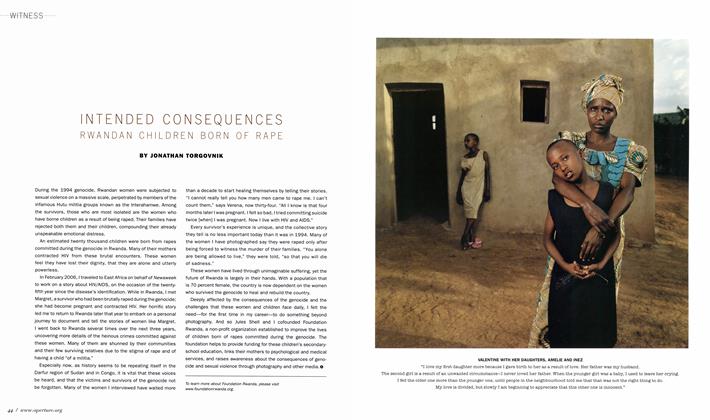

Witness

WitnessIntended Consequences Rwandan Children Born Of Rape

Spring 2009 By Jonathan Torgovnik