Rediscovered Books and Writings

Redux

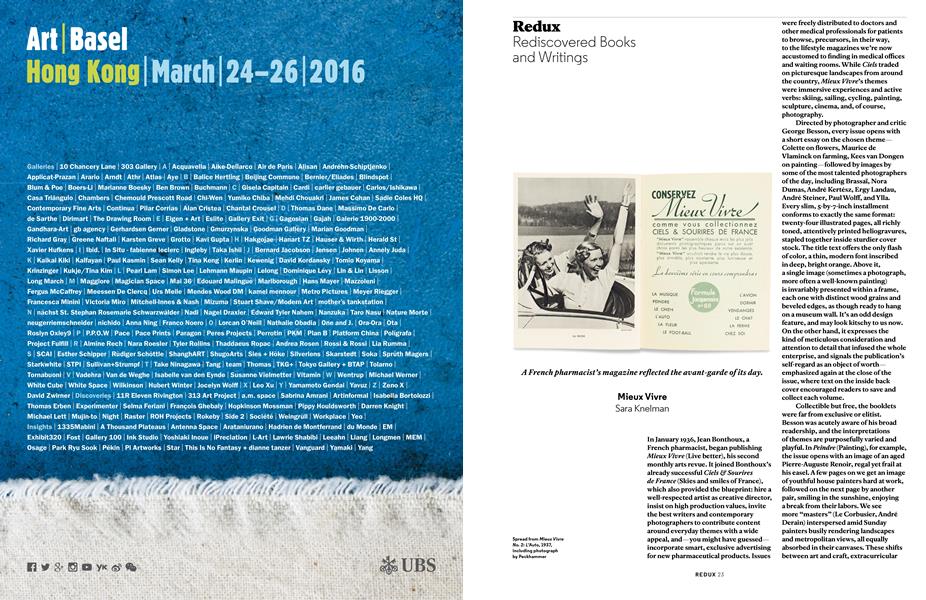

A French pharmacist's magazine reflected the avant-garde of its day.

Mieux Vivre

Sara Knelman

In January 1936, Jean Bonthoux, a French pharmacist, began publishing Mieux Vivre (Live better), his second monthly arts revue. It joined Bonthoux’s already successful Ciels & Sourires de France (Skies and smiles of France), which also provided the blueprint: hire a well-respected artist as creative director, insist on high production values, invite the best writers and contemporary photographers to contribute content around everyday themes with a wide appeal, and—you might have guessed— incorporate smart, exclusive advertising for new pharmaceutical products. Issues were freely distributed to doctors and other medical professionals for patients to browse, precursors, in their way, to the lifestyle magazines we’re now accustomed to finding in medical offices and waiting rooms. While dels traded on picturesque landscapes from around the country, Mieux Vivre9s themes were immersive experiences and active verbs: skiing, sailing, cycling, painting, sculpture, cinema, and, of course, photography.

Directed by photographer and critic George Besson, every issue opens with a short essay on the chosen theme— Colette on flowers, Maurice de Vlaminck on farming, Kees van Dongen on painting—followed by images by some of the most talented photographers of the day, including Brassaï, Nora Dumas, André Kertész, Ergy Landau, André Steiner, Paul Wolff, and Ylla. Every slim, s-by-7-inch installment conforms to exactly the same format: twenty-four illustrated pages, all richly toned, attentively printed heliogravures, stapled together inside sturdier cover stock. The title text offers the only flash of color, a thin, modern font inscribed in deep, bright orange. Above it, a single image (sometimes a photograph, more often a well-known painting) is invariably presented within a frame, each one with distinct wood grains and beveled edges, as though ready to hang on a museum wall. It’s an odd design feature, and may look kitschy to us now. On the other hand, it expresses the kind of meticulous consideration and attention to detail that infused the whole enterprise, and signals the publication’s self-regard as an object of worth— emphasized again at the close of the issue, where text on the inside back cover encouraged readers to save and collect each volume.

Collectible but free, the booklets were far from exclusive or elitist.

Besson was acutely aware of his broad readership, and the interpretations of themes are purposefully varied and playful. In Peindre (Painting), for example, the issue opens with an image of an aged Pierre-Auguste Renoir, regal yet frail at his easel. A few pages on we get an image of youthful house painters hard at work, followed on the next page by another pair, smiling in the sunshine, enjoying a bréale from their labors. We see more “masters” (Le Corbusier, André Derain) interspersed amid Sunday painters busily rendering landscapes and metropolitan views, all equally absorbed in their canvases. These shifts between art and craft, extracurricular hobby and paid labor are apt reflections of the lives of the jobbing photographers who made them, and of a wider cultural sensibility, one that preferred not to distinguish high from low, placing value instead on pleasure and pride. In a similar way, Mieux Vivre9s heterogeneity also makes its present-day appeal hard to pin down—we may be interested in the photographs, but historians of pharmacology or collectors of vintage advertising might find it equally fascinating for different reasons.

The images were, let’s not forget, in the service of selling pharmaceuticals, and astutely set against ads for a new drug called Formule Jacquemaire n° 60. Readers were led to believe that taking this pill twice daily could support the energy levels and general health needed to pursue all of the wonderful fun illustrated by the pictures. The ads were often conceived and executed with each issue’s subject in mind: A Formule Jacquemaire ad in L9Auto (The car) gives readers a jagged motorway route, with junctures along the line listing the evolving benefits of the product, from preventing warts to combating depression to, ultimately, deterring precancerous cell development. In Lire (Reading), an ad showing a young girl contentedly absorbed in a book carries the captions “Lire un bon livre... Quiétude!99 (Read a good book... tranquility!) and “Formule Jacquemaire n°6o... également Quiétude!99 (... also tranquility!), aligning the calm moments of reading with the general peace of mind the drug might furnish. There are also ironic discords, most obviously the many images of habitual smokers writing, painting, playing cards, and taking photos—activities that go especially well with cigarettes, it would seem—that share space with a drug marketed for use “aux terrains précancéreux” (in precancerous territory). Indeed, November 1937 was dedicated to Fumer (Smoking), portraying smoking as a lifestyle choice that might go hand-in-hand with these everyday lozenges.

The forty-five published issues of Mieux Vivre were of their time, produced at the close of a creatively potent decade when Surrealism, jazz, and experimental literature flourished, and, like a lot of mass-cultural products, also slipped away with it. Bonthoux died in 1937 in the midst of the magazine’s short life; it would abruptly fold two years later. September 1939 ushered in the German invasion of Poland and the publication of the series’s final published issue: Les Fruits.

(The subsequent three issues, on wine, trees, and singing, were advertised but never completed.) By the time the war ended many of the contributors had fled Europe, and the lighthearted energy of the period was scattered or dissolved. Surviving copies also scattered, though they are easy enough to find for cheap in French used bookstores. The sudden end and perpetual incompleteness of Mieux Vivre are heavyhearted reminders of the immense creative potential of the time, which would never be fully realized. But the revue’s spirit is remarkably intact, a testament to the inventive collaborations between art and commerce, the expanding and conflicting possibilities for photography, and the vivid imaginations and experimental spark of this moment in and around Paris of the 1930s. Mieux Vivre? Maybe. Then again, living better so often looks best in retrospect.

Sara Knelman is a writer, curator, and lecturer living in Toronto.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

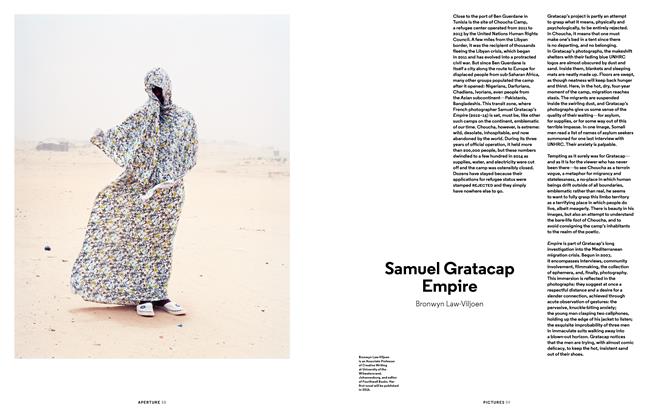

PicturesSamuel Gratacap Empire

Spring 2016 By Bronwyn Law-Viljoen -

Pictures

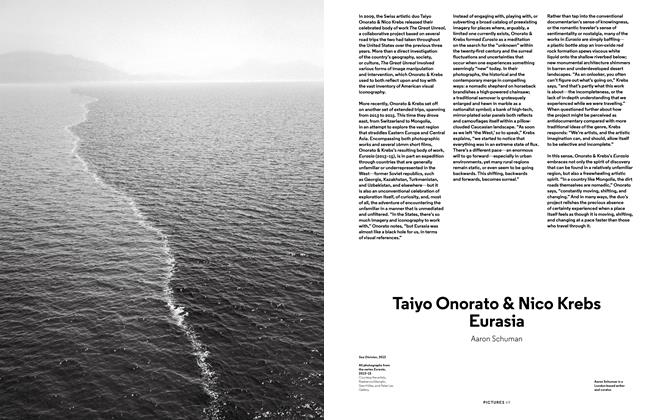

PicturesTaiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs Eurasia

Spring 2016 By Aaron Schuman -

Pictures

PicturesTrevor Paglen Landing Site

Spring 2016 By Brian Wallis -

Pictures

PicturesJacob Aue Sobol Arrivals And Departures

Spring 2016 By Pico Iyer -

Pictures

PicturesYto Barrada Dinosaur Road

Spring 2016 By Carmen Winant -

Pictures

PicturesIshikawa Naoki Archipelago

Spring 2016 By Niwa Harumi

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Sara Knelman

-

Words

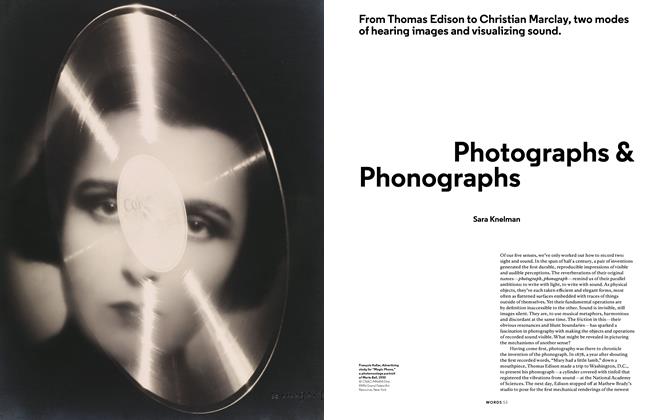

WordsPhotographs & Phonographs

Fall 2016 By Sara Knelman -

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Summer 2018 By Sara Knelman -

Pictures

PicturesThirza Schaap

Spring 2019 By Sara Knelman -

Words

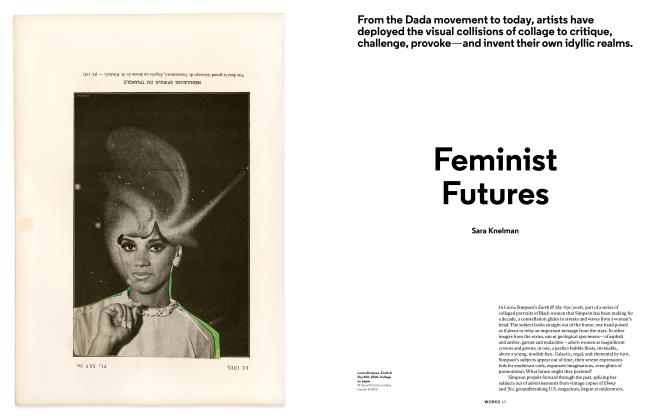

WordsFeminist Futures

Winter 2020 By Sara Knelman -

Etienne Courtois

SUMMER 2022 By Sara Knelman -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWThe Lives Of Documents

WINTER 2023 By Sara Knelman

Redux

-

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Fall 2015 -

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Summer 2016 -

Redux

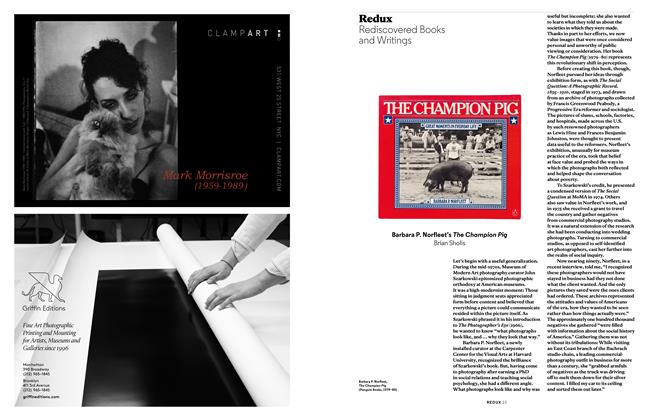

ReduxBarbara P. Norfleet's The Champion Pig

Spring 2015 By Brian Sholis -

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Fall 2017 By Eric Banks -

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Winter 2017 By Maika Pollack -

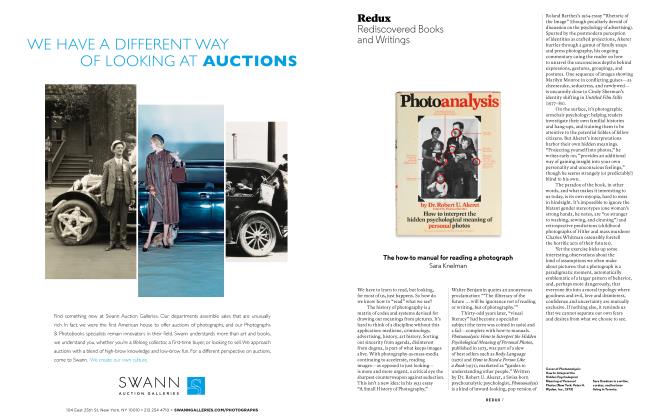

Redux

ReduxRediscovered Books And Writings

Spring 2017 By Sara Knelman