Horacio Coppola

Sarah Hermanson Meister

That Horacio Coppola's photographs might reasonably be included in this context—Photography As You Don't Know It—neatly illustrates the dearth of attention given to artists working outside the cities typically associated with photographic modernism: Paris, London, and New York. Coppola (1906-2012) was a founding figure of the modernist traditions in his native Argentina, yet there are precious few significant collections of his work. He has nevertheless been the subject of major exhibitions (with catalogue texts translated into English) by IVAM Centre Julio González, Valencia, and Fundación Telefónica, Madrid, among others, and his work resonates convincingly with the contemporary practices of Manuel Alvarez Bravo, Use Bing, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and many others whose paths he almost certainly didn’t cross. Even before he studied with Walter Peterhans at the Bauhaus in Berlin, between October 1932 and April 1933, Coppola’s photographs bore a striking resemblance to those of the European avant-garde, using extreme camera angles, rushing perspectives, and asymmetrical cropping to evoke a distinctively modern urban experience.

Coppola was born to an affluent Italian immigrant family in Buenos Aires; his older brother taught him the basics of photography when he was a teenager. He was deeply engaged with experimental cinema, founding the Buenos Aires Film Club in 1929. The city was muse to Coppola and his good friend Jorge Luis Borges. Their wanderings through its streets together in the late 1920s led to two photographs by Coppola that illustrated the first edition of Borges’s essays on Argentine poet Evaristo Carriego in 1930. Coppola purchased a Leica during his first excursion to Europe, from December 1930 through May 1931, but it was his second trip, in October 1932, that marked several turning points: in Berlin he met Grete Stern, his future wife; fine-tuned his technical skills with Peterhans; and began experimenting with filmmaking. As Germany’s political environment turned increasingly hostile, Coppola followed Stern to London in December 1933 and continued to expand his oeuvre as a photographer and filmmaker. They married and returned to Argentina in August 1935. The two-person exhibition of their work in the offices of the avant-garde literary magazine Sur is considered the first exhibition of modern photography in Argentina.

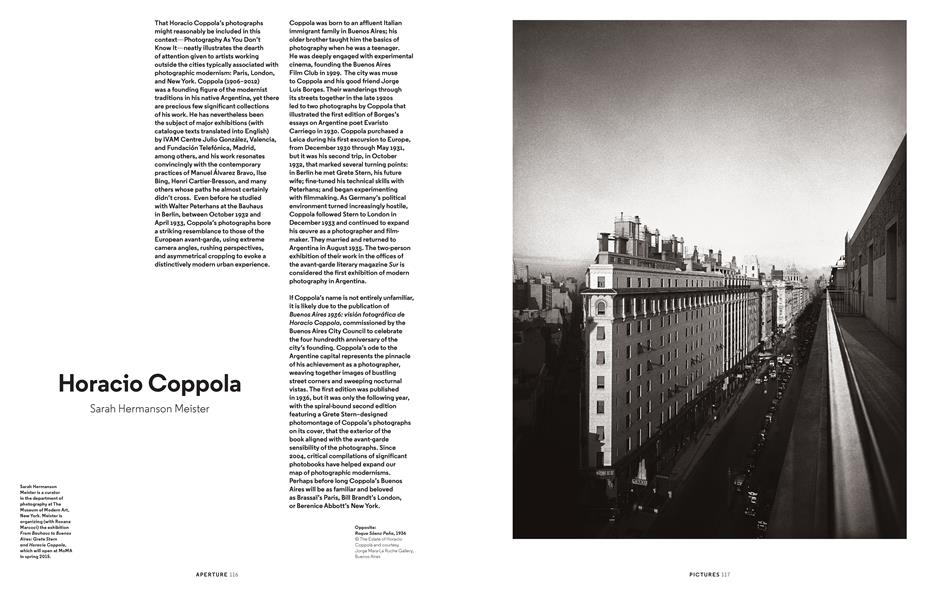

If Coppola’s name is not entirely unfamiliar, it is likely due to the publication of Buenos Aires 1936: vision fotográfica de Horacio Coppola, commissioned by the Buenos Aires City Council to celebrate the four hundredth anniversary of the city's founding. Coppola’s ode to the Argentine capital represents the pinnacle of his achievement as a photographer, weaving together images of bustling street corners and sweeping nocturnal vistas. The first edition was published in 1936, but it was only the following year, with the spiral-bound second edition featuring a Grete Stern-designed photomontage of Coppola’s photographs on its cover, that the exterior of the book aligned with the avant-garde sensibility of the photographs. Since 2004, critical compilations of significant photobooks have helped expand our map of photographic modernisms. Perhaps before long Coppola’s Buenos Aires will be as familiar and beloved as BrassaTs Paris, Bill Brandt’s London, or Berenice Abbott’s New York.

Sarah Hermanson Meister is a curator in the department of photography at The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Meister is organizing (with Roxana Marcoci) the exhibition From Bauhaus to Buenos Aires: Grete Stern and Horacio Coppola, which will open at MoMA in spring 2015.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Pictures

PicturesPaul Trevor

Winter 2013 By Chris Boot -

Pictures

PicturesRosângela Rennó

Winter 2013 By Thyago Nogueira -

Pictures

PicturesMarianne Wex

Winter 2013 By David Campany -

Pictures

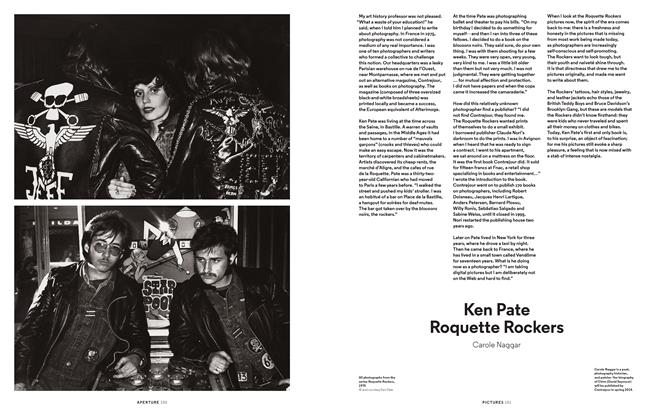

PicturesKen Pate Roquette Rockers

Winter 2013 By Carole Naggar -

Pictures

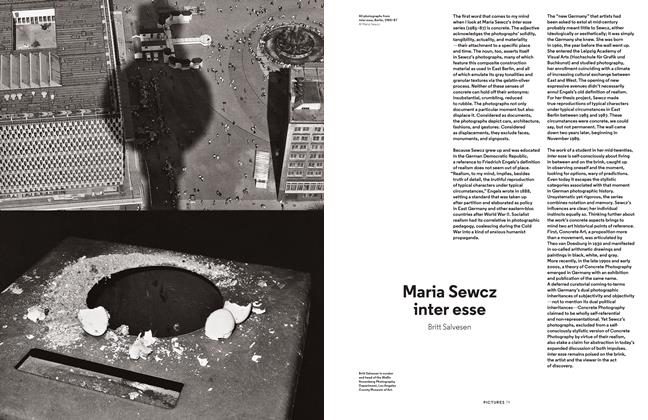

PicturesMaria Sewcz Inter Esse

Winter 2013 By Britt Salvesen -

Pictures

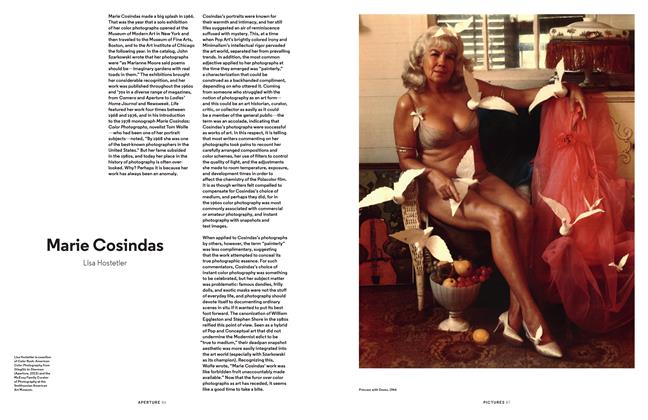

PicturesMarie Cosindas

Winter 2013 By Lisa Hostetler

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Sarah Hermanson Meister

Pictures

-

Pictures

PicturesPaul Mpagi Sepuya

Summer 2019 -

Pictures

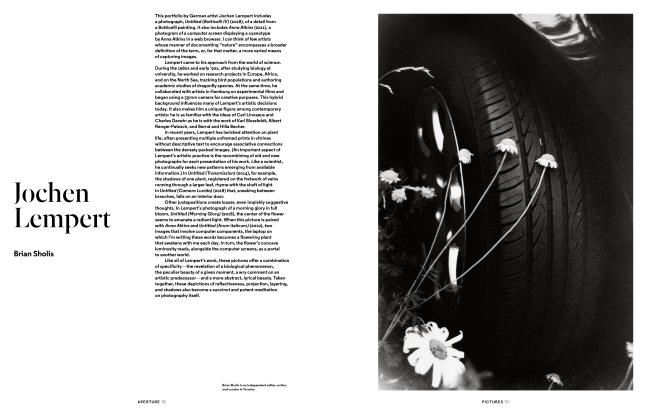

PicturesJochen Lempert

Spring 2019 By Brian Sholis -

Pictures

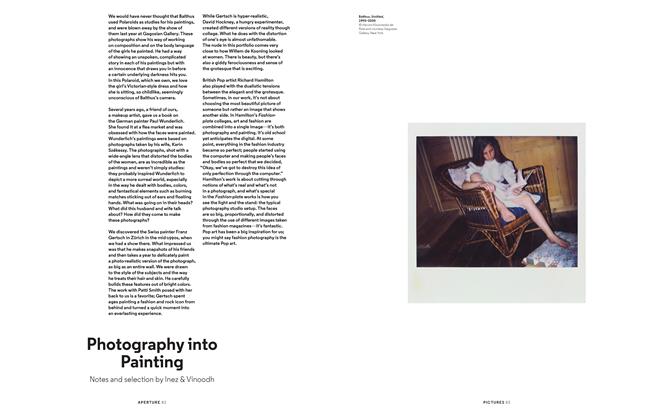

PicturesPhotography Into Painting

Fall 2014 By Inez -

Pictures

PicturesNadine Ijewere

Fall 2017 By M. Neelika Jayawardane -

Pictures

PicturesStephen Tourlentes

Spring 2018 By Mabel O. Wilson -

Pictures

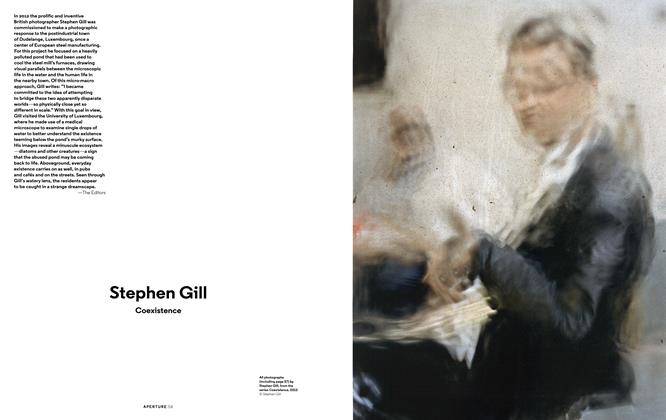

PicturesStephen Gill Coexistence

Summer 2013 By The Editors