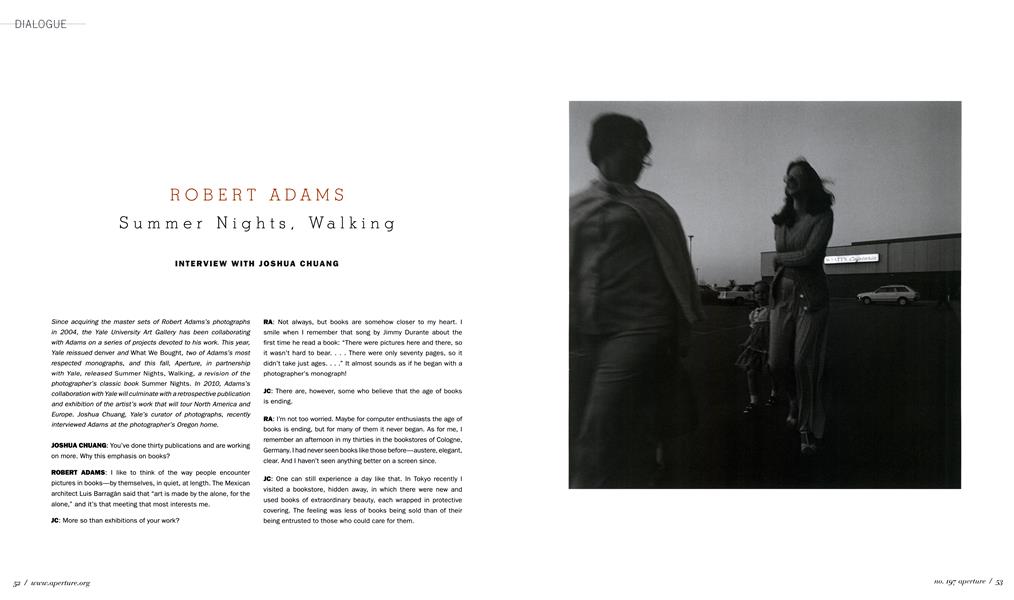

ROBERT ADAMS Summer Nights, Walking

DIALOGUE

JOSHUA CHUANG

Since acquiring the master sets of Robert Adams's photographs in 2004, the Yale University Art Gallery has been collaborating with Adams on a series of projects devoted to his work. This year, Yale reissued denver and What We Bought, two of Adams's most respected monographs, and this fall, Aperture, in partnership with Yale, released Summer Nights, Walking, a revision of the photographer's classic book Summer Nights. In 2010, Adams’s collaboration with Yale will culminate with a retrospective publication and exhibition of the artist’s work that will tour North America and Europe. Joshua Chuang, Yale’s curator of photographs, recently interviewed Adams at the photographer's Oregon home.

JOSHUA CHUANG: You’ve done thirty publications and are working on more. Why this emphasis on books?

ROBERT ADAMS: I like to think of the way people encounter pictures in books—by themselves, in quiet, at length. The Mexican architect Luis Barragán said that “art is made by the alone, for the alone,” and it’s that meeting that most interests me.

JC: More so than exhibitions of your work?

RA: Not always, but books are somehow closer to my heart. I smile when I remember that song by Jimmy Durante about the first time he read a book: “There were pictures here and there, so it wasn’t hard to bear. . . . There were only seventy pages, so it didn’t take just ages. . . .” It almost sounds as if he began with a photographer’s monograph!

JC: There are, however, some who believe that the age of books is ending.

RA: I’m not too worried. Maybe for computer enthusiasts the age of books is ending, but for many of them it never began. As for me, I remember an afternoon in my thirties in the bookstores of Cologne, Germany. I had never seen books like those before—austere, elegant, clear. And I haven’t seen anything better on a screen since.

JC: One can still experience a day like that. In Tokyo recently I visited a bookstore, hidden away, in which there were new and used books of extraordinary beauty, each wrapped in protective covering. The feeling was less of books being sold than of their being entrusted to those who could care for them.

RA: And that in the heart of a famously “advanced” city. . . .

JC: You’ve republished Summer Nights, but with an altered title and expanded selection of images. What motivated you to change it?

RA: I wanted to get closer to the experience of actually being there. On the assumption—debatable, I admit—that it usually helps to know the facts. What’s old age for, after all, if not to attempt to be more accurate? My original goal was mainly to document some of the evening peace and mystery that I remember as a child, those dusks when the lightning bugs came out. But I should have been suspicious—I hadn’t seen any lightning bugs for over a quarter century. And after Summer Nights was published, when people asked about the experience of making the pictures, I found myself admitting to some unpeaceful incidents, experiences that led me to hire a bodyguard.

JC: Why were you so compelled to make photographs that required such precautions?

RA: Night offers wonderful opportunities. Very little has been done with it, relatively. For any given scene you can, depending on the exposure, discover an amazing range of things. Though it’s hard. A lot is unpredictable—satellites and planes and cars, for example. And it is visually tiring to keep in focus in very low light, and then suddenly to stare into something like car lights. And safety is an issue. There you are with what is obviously valuable equipment, and as you concentrate into the finder—I was using a Flasselblad—you don’t have much peripheral vision.

JC: So what actually happened as you worked?

RA: Mostly nothing bad. But one night someone tried twice within a few minutes to run us down (I had reflective stripes on my parka and on the tripod, and we kept a flashing yellow strobe going except during the exposures). Another evening, near Fort Carson, someone threw an artillery simulator, a kind of super-sized firecracker, into the street near us. And a week after we completed the project there was a triple murder inside a house by which we had walked at the same time of night. I remember the relief of getting back home at two or three o’clock in the morning, pulling into our fenced backyard with its big old ash tree, and the back porch light left on by Kerstin.

JC: Given the nature of these incidents, why did you, in Summer Nights, originally offer the impression of a more serene experience?

RA: Because there is something quiet about the night. I don’t want to lose track of that—it’s important. The problem is that it’s not the whole story. And so as the years passed I began to wish I had made the book tougher, closer to what I had tried to do with The New West, denver, and What We Bought. A little more in the spirit of something my Shakespeare teacher said, wryly—that “books should bite people.” So I went back and discovered on the old proof sheets that there was considerable evidence of a mixed experience. It was a reminder that, though I could sometimes be adventurous when I was out photographing, I could also be a coward at the editing table. I don’t fully know why that is, except that it’s so wonderful to be out shooting. When I’m in thrall to a subject, it seems to elicit a better me than when I’m standing in the studio, perhaps having read the newspaper, done all manner of drudgery, and re-entered the tame world of being a careerist and all the rest of the things that you don’t want to be but inevitably slip into being.

JC: Would you comment on your editing process, since it seems to be at the heart of your work as a photographer?

RA: I think photography is editing, start to finish—editing life, selecting part of it to stand for the whole. The process starts, obviously, with what you choose to include in the finder when you make the exposure. It continues as you study the contact sheets or thumbnails in order to decide which to enlarge. It goes on, sometimes for years, as you try to determine which enlargements are successful. Dorothea Lange, one of my heroes, used to ask herself, sotto voce, “Is it a picture? Is it a picture?” Most photographers are like that, confident one day and unsure the next. And then there is the long search for which pictures may strengthen each other, and in what relationships. That final step usually involves for us laying out all the conceivably appropriate pictures for a book in a line, in a roughly plausible sequence, after which we make a stack of the pictures in that order and go through it to see how they might work as singles or doubles on a spread. Those two steps are then repeated over and over again. We’ve found that we have to keep approaching the problem in both ways in order to find the overall structure of a book, as well as how the book will work at arm’s length, two pages at a time.

JC: When you say “we,” you mean you and your wife, Kerstin?

RA: Once a picture is taken (a misleading verb, I’ve always thought), the rest of the process relies on her help. She is visually informed and acute, and concerned with the subjects to the same degree that I am. I watch her reactions closely—she is quiet—because I have learned that she is often right and that I can be very wrong.

I also watch the reactions of other people that I trust—people who know what photography can do and what I am trying to do. They are courteous, of course, but I try to notice if there are hesitations, and if there are, I make a mental note to check my judgment again, later.

The scary part for me is having to make the final judgments myself. In some respects it would be better if my colleagues made the decisions. The book would almost certainly be more graceful, more consistent in quality, and perhaps even more coherent. But it would also be a little farther from the compulsion that results from encountering the subjects firsthand. And so perhaps a little less useful.

JC: Are there particular pictures you feel are emblematic of the new tone you tried to establish in Summer Nights, Walking?

RA: At one extreme, there is the picture to which we came to refer as “the murder house.” It isn’t literally the scene of the crime I mentioned, but its appearance is representative of the occasionally sinister aspect of night. Other pictures that might qualify are a couple with shallow focus and an indication of wind. Night photography tends toward simplification, and that may make metaphor too easy. The relaxed structure of these pictures borders on chaos, the enemy of meaning.

JC: You wrote in 1977, in the introduction to denver, that the city’s inhabitants “participate in urban chaos” but are themselves “admirable.” Do you still believe this?

RA: I’d probably be more specific about the people I endorse. And inclined to note the tragic nature that we all have in common. In a recent Paris Review interview the writer Marilynne Robinson was asked if she worried about being too pessimistic. Her reply was “I worry that I’m not pessimistic enough." I share that feeling. Although neither she nor any artist is without hope. If they were, they wouldn’t bother.

JC: Dorothea Lange once said that she hoped that the generation of photographers following hers would focus on the American city and what was happening in the suburbs. Is there a particular subject you’d like to see the next generation take on?

RA: What she wanted still seems right, but it remains a tall order. One of the things that I most hope to find when I speak with young photographers is a readiness to ask almost impossible things of themselves, the sort of things that demand three or four years and that might result in fifty or seventy-five pictures of an important, life-sized subject. I want to repeat to them Miguel de Unamuno’s blessing: “May God deny you peace but give you glory.”

Let me add one thing that might at first seem at odds with my wanting to toughen up Summer Nights—that the goal of art is affirmation. Of course if you get affirmation on the cheap it can be easily dismissed, which is why I wanted Summer Nights to be more than a record of childhood innocence. But the purpose of art is, in the end, to find beauty, and by that to share an intuition of promise.

This past spring there was a show titled Into the Sunset at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was about photography’s picture of the American West, and though I didn’t see the exhibition I did study the catalog. It raised an important problem that confronts everybody, East and West. On the one hand there were landscapes, the more recent of which, my own included, documented worn, abused places. Together with these views there were pictures of people, and the more recent of them seemed, in the main, to be portraits of the lost. The issue raised by the show seemed to be whether there are affirmable days or places in our deteriorating world. Are there scenes in life, right now, for which we might conceivably be thankful? Is there a basis for joy or serenity, even if felt only occasionally? Are there grounds now and then for an un-ironic smile?

Every artist and would-be artist should, I think, recognize a responsibility to try, without lying, to answer those questions with a yes.O

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

DialogueNick Knight: Showman

Winter 2009 By Diane Smyth -

Essay

EssayChildren Of The Revolution Contemporary Iranian Photography

Winter 2009 By Anthony Downey -

Archive

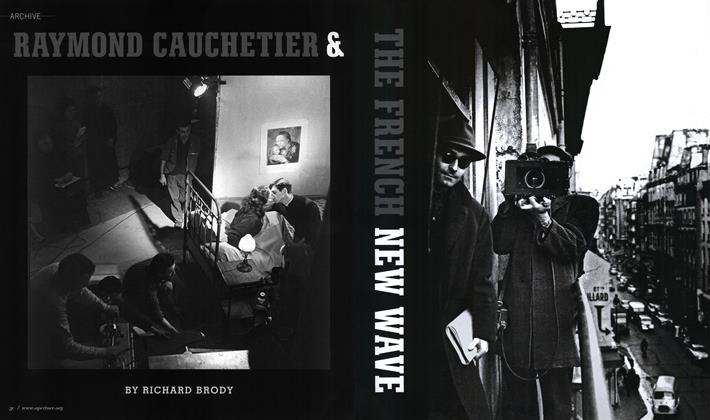

ArchiveRaymond Cauchetier & The French New Wave

Winter 2009 By Richard Brody -

Mixing The Media

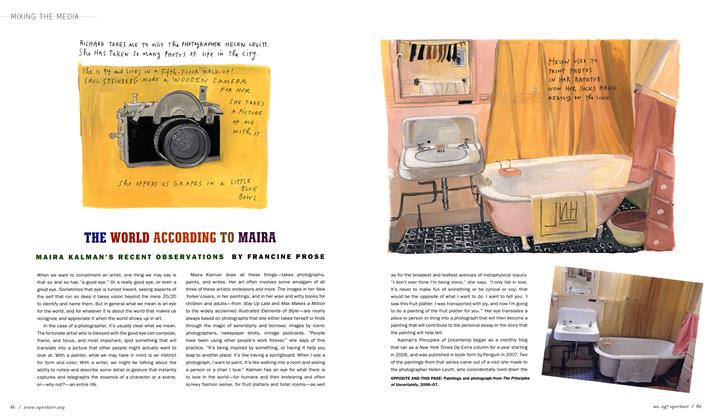

Mixing The MediaThe World According To Maira

Winter 2009 By Francine Prose -

Work And Process

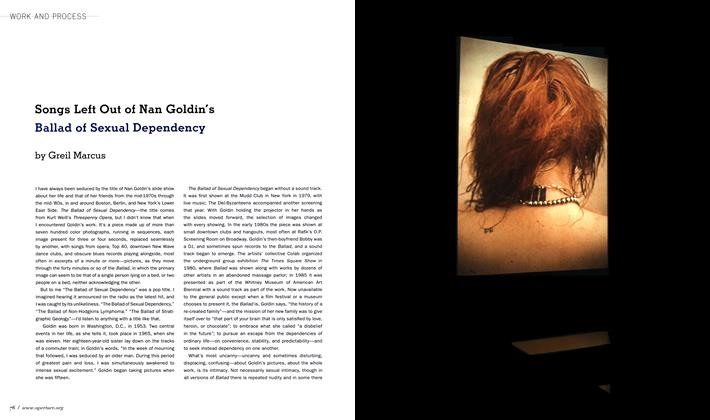

Work And ProcessSongs Left Out Of Nan Goldin's Ballad Of Sexual Dependency

Winter 2009 By Greil Marcus -

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressCarrie Mae Weems History And Dreams

Winter 2009 By A. M. Weaver

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Dialogue

-

Dialogue

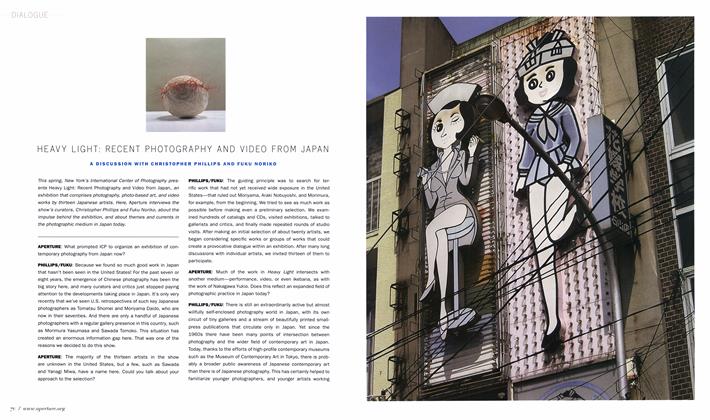

DialogueHeavy Light: Recent Photography And Video From Japan

Summer 2008 -

Dialogue

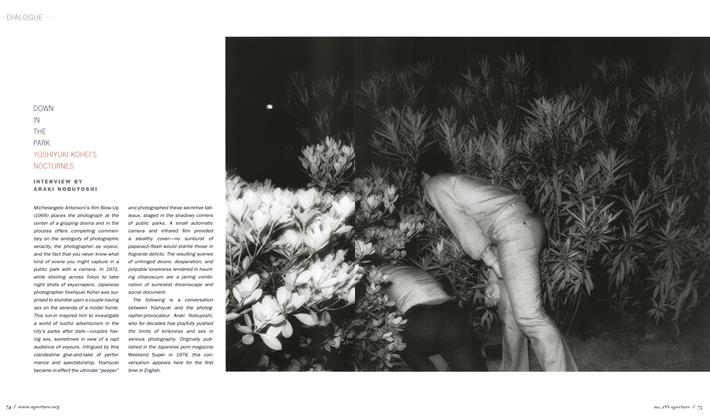

DialogueDown In The Park: Yoshiyuki Kohei's Nocturnes

Fall 2007 By Araki Nobuyoshi -

Dialogue

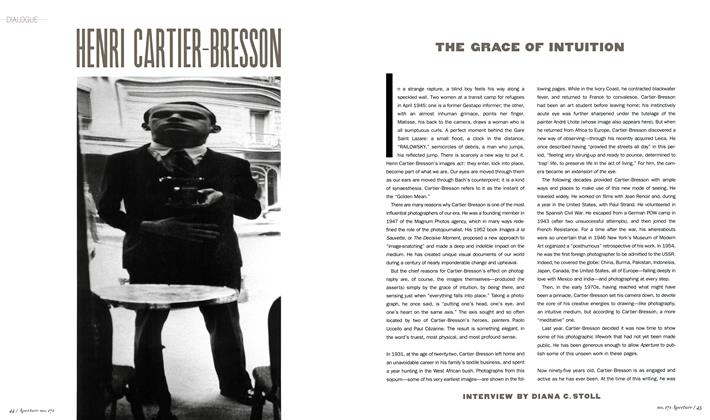

DialogueHenri Cartier-Bresson

Summer 2003 By Diana C. Stoll -

Dialogue

DialogueInvasion 68: Prague

Fall 2008 By Melissa Harris -

Dialogue

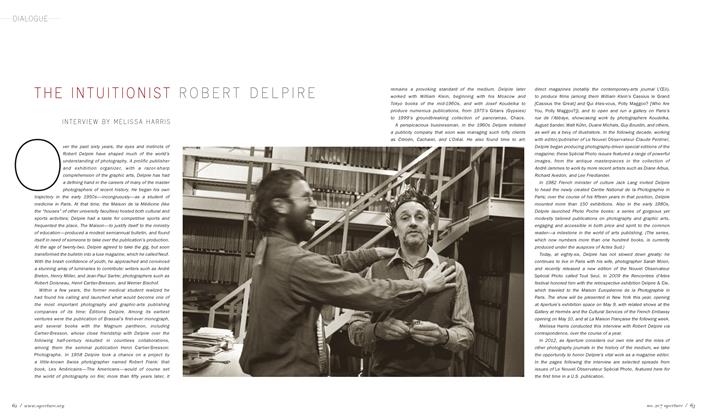

DialogueThe Intuitionist Robert Delpire

Summer 2012 By Melissa Harris -

Dialogue

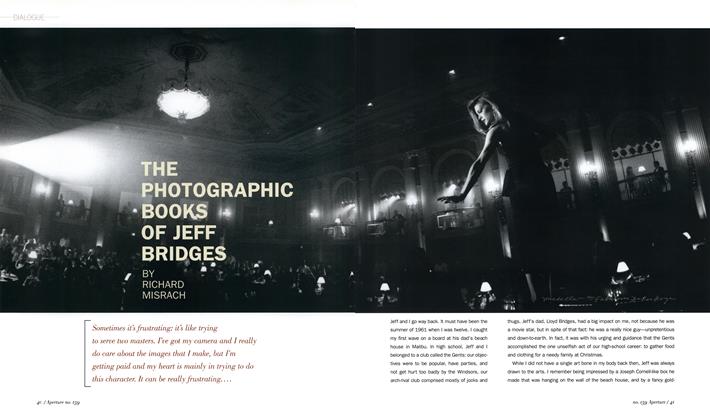

DialogueThe Photographic Books Of Jeff Bridges

Spring 2000 By Richard Misrach