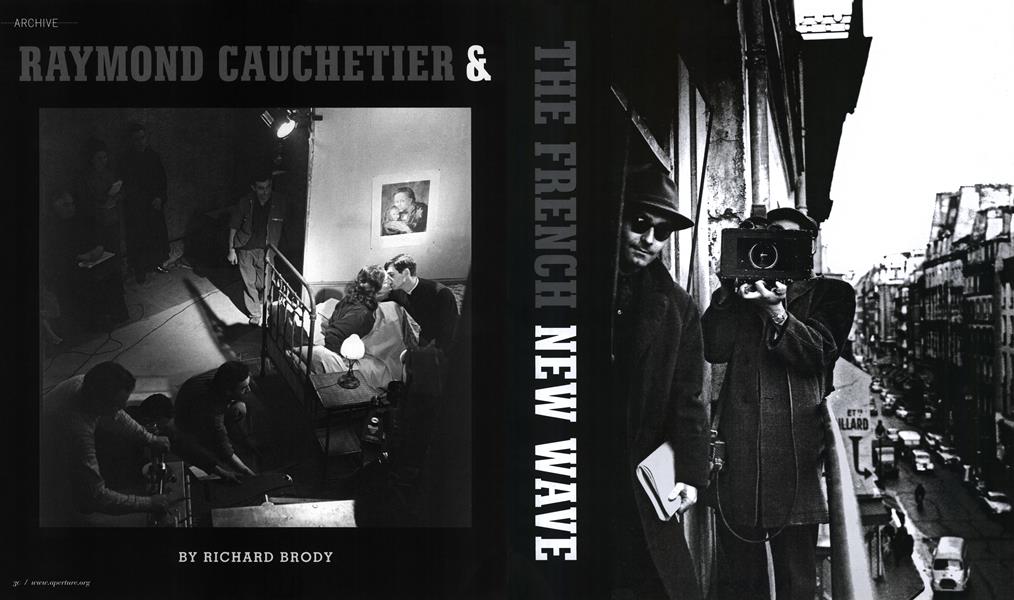

RAYMOND CAUCHETIER & THE FRENCH NEW WAVE

ARCHIVE

RICHARD BRODY

In the mid-1950s, before the French New Wave burst onto the international scene with audaciously original films, many of its young luminaries (Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, and their inspiring elder, Eric Rohmer) were making their names as film critics. In their writings, they advocated what became known as the politique des auteurs, or “auteur policy": the recognition that directors are the artists whose personal imprint makes movies into art—that they are, in effect, the “authors” of their films. These critics themselves would soon become authorial filmmakers, whose extraordinarily daring and personal films definitively transformed the art of the cinema.

The films—including Truffaut’s Les quatre cents coups (The 400 Blows, 1959) and Godard’s À bout de souffle (Breathless, 1960)—are proof of the directors’ artistry. But their radical ideas about cinema were built into the way they made their films. Fortunately, there is visual documentation of the New Wave at work—most crucially, the evocative photographs by Raymond Cauchetier, who made the publicity stills for many of the key films of the French New Wave between 1959 and 1968. His photographs transcend their commercial origins to provide a revelatory view of the movement and its methods; the images are vibrant with the spirit of the New Wave.

Raymond (and so I shall call him, as he is a friend) was born in 1920. He came to the business of photography by chance, when he was already in his thirties: while serving in the press corps of the French air force in Indochina, he bought himself a Rolleiflex and started taking pictures only because his unit had no budget for a still photographer. Staying in the region after the war, Raymond was busy in Cambodia photographing the temples of Angkor Wat when, in 1957, director Marcel Camus arrived there to make Mort en fraude (Fugitive in Saigon), a film based on a novel by Raymond’s friend Jean Hougron. In order to save the cost of flying a photographer in from France, Camus hired Raymond.

When he returned to France, Raymond tried to find work as a photojournalist, but instead was hired to take pictures for Hubert Serra, a publisher of photo-romans (“photo-novels”— in effect, graphic novels in which photographs are used in lieu of drawings). He met several of Serra’s acquaintances, among them the film producer Georges de Beauregard; Raoul Coutard, a veteran of the photographic corps of the French army in Indochina and a fledgling cinematographer; and the young Godard, who was working as a critic and cobbling together odd jobs while angling to make films. In 1959, after the success of Truffaut’s Les quatre cents coups at the Cannes film festival, Beauregard agreed to produce Godard’s first feature, À bout de souffle, and brought in

Coutard as the cinematographer and Cauchetier as the set photographer.

What Raymond saw during that shoot was astonishing; how he captured it is equally miraculous. Godard’s methods were very unusual and Raymond knew it. The director worked without a script, telling his actors what to do just before each shot and calling out lines while the camera was rolling. Seeing what was going on, Raymond thought (as did many on the set) that the resulting footage would be impossible to cut together and would never be released. His pictures from the shoot display Godard’s originality more incisively than even the contemporaneous journalistic accounts. Raymond shows the crew—at least those few of its members who fit—at work in a tight hotel room in the Latin Quarter; there, Coutard applied the sort of rough-and-ready lighting scheme that he had learned while working for Serra. Raymond documented a shoot in a photographer’s studio, with Godard pushing a wheelchair in which Coutard sat holding the camera (there was no money for tracking rails).

Most remarkably, Raymond caught Godard snatching the essence of his film from the life of the Paris streets. He snapped the director shooting on the Champs-Elysées, with his two stars, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg. They walked on the avenue as the movie camera secretly trailed behind them—it and Coutard were inside a three-wheeled mail cart with a small hole bored in its front. An assistant pushed the cart, and Godard followed along at a distance to survey the action inconspicuously.

A pair of extraordinary images (one of which is seen here) show how the film’s last shots, of the death of Belmondo’s character under Seberg’s gaze, were made. In the movie, the street around the characters is quiet and relatively unpopulated. Godard, however, had not arranged for crowd control, and Belmondo had to feign his death agony (with a few sardonic touches) while the neighborhood’s passersby, who are not seen in the film, clustered around the camera and here seem to be stepping on his feet. (A few crew members, including the script supervisor and the assistant director, melted into the crowd.)

In 1960, after À bout de souffle was released to great acclaim as the revolutionary work it is, Beauregard produced the first feature by Godard’s friend Jacques Rozier, Adieu Philippine. Working with a very small budget but on a large scale, Rozier managed todo a longtrackingshoton a deserted road in Corsica, under Raymond’s attentive eye, with an old, gutted car that had its tires deflated and was intentionally weighed down with as many crew members as possible.

Truffaut is seen doing a tracking shot the same way on Baisers volés (Stolen Kisses, 1968). In that film, Truffaut pays homage to the Cinémathèque Française, where the New Wave was schooled by its founder and animating spirit, Henri Langlois. Raymond found Langlois and Truffaut flanking the film’s young star, Jean-Pierre Léaud, and created a sort of three-generational portrait of the New Wave.

The New Wave—as Raymond’s photographs show—was not just a product of low-budget expedients; it was a truly personal cinema based in the aspiration to fuse life behind and in front of the camera. Godard’s third film, Une femme est une femme (A Woman Is a Woman), shot in late 1960, starred Anna Karina, who would soon become the director’s wife. Raymond caught moments of latent strife and happiness in the couple’s relationship off-camera, as well as the blend of tenderness and tension on the set. Truffaut’s 1961 shoot of Jules et Jim unfurled in an atmosphere of lighthearted but serious intimacy between Truffaut and Jeanne Moreau, which intensified the film’s portrayal of grand and tragic romance.

In 1968 Raymond stopped working as an on-set still photographer, because the vocation wasn’t sufficiently remunerative. The New Wave itself was going through a strange moment: far from having ended, it was, in a way, being re-launched, with Rivette, Truffaut, Rohmer, and Chabrol achieving new successes after some notorious commercial disasters. But Godard had withdrawn from the industry and then began to make expressly politicized films and Beauregard had suffered significant financial reversals. With the political turbulence of May 1968 and its conservative aftermath, the true canonization of the New Wave in French culture would lie far in the future.

In his cinema photographs from 1959 to 1968, Raymond preserved the youth of the French New Wave—the exuberant first flowering of a new generation’s innovations, as well as the brash and vigorous styles, artistic and personal, that would so rapidly inspire young people in France and around the world. Raymond’s photographs are themselves central works of the New Wave. His artistic connection with that movement comes through in several recent notes I have received from him, including the following observation:

I’ve never received the slightest advice from a professional. I’ve always improvised, and invented what I needed to do, with my own inspiration. Is that why some people think my photos never look like other people’s?

Like the New Wave directors, Raymond is an autodidact, for whom the question is not one of technique but of nature: “I think that some people have the ‘gift’ and others don’t, and all the courses in the world won’t change that.” But he expresses an artistic humility that is truly touching and that converges with the essentially documentary essence of the French New Wave:

I am not an artist, but a reporter. The artist creates, and tries to impose his ego in all circumstances. The reporter, however, is a witness. I think that reality is, in most cases, extraordinary enough that the photographer needn’t feel it necessary to add his grain of salt.

Nonetheless, in these images, Raymond Cauchetier, a witness to art, made art by bearing true witness.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

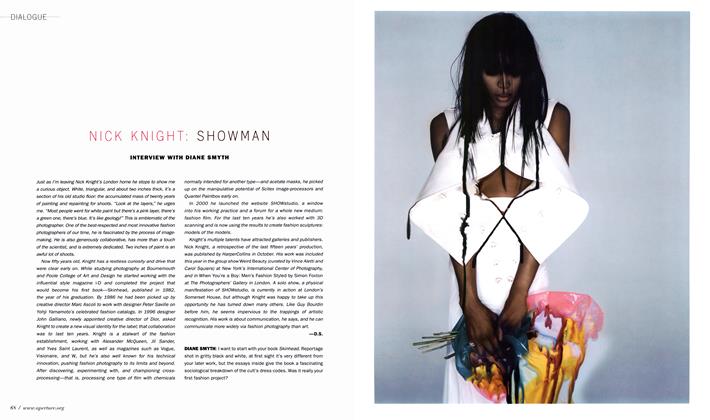

DialogueNick Knight: Showman

Winter 2009 By Diane Smyth -

Essay

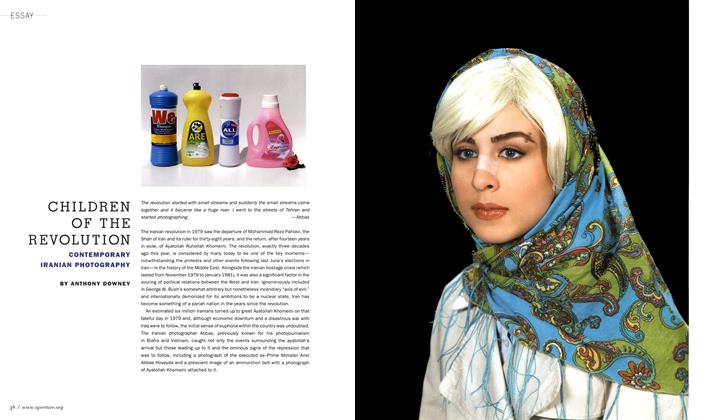

EssayChildren Of The Revolution Contemporary Iranian Photography

Winter 2009 By Anthony Downey -

Dialogue

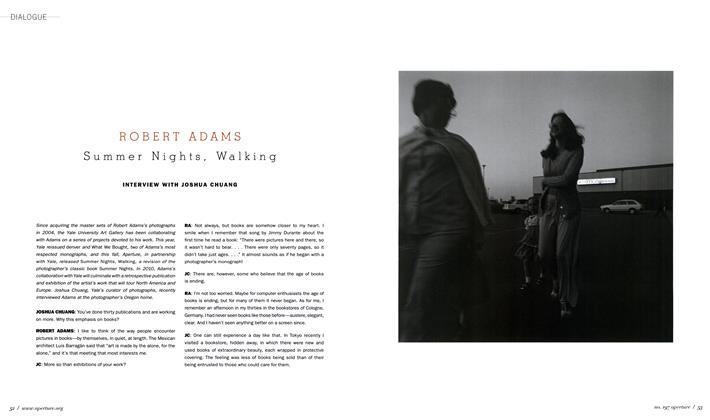

DialogueRobert Adams Summer Nights, Walking

Winter 2009 By Joshua Chuang -

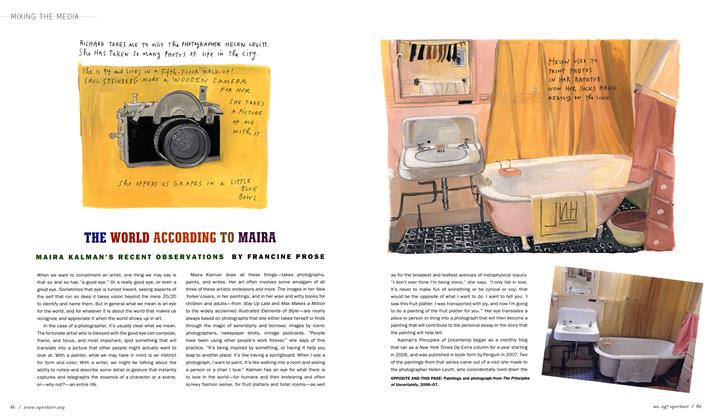

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaThe World According To Maira

Winter 2009 By Francine Prose -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessSongs Left Out Of Nan Goldin's Ballad Of Sexual Dependency

Winter 2009 By Greil Marcus -

Work In Progress

Work In ProgressCarrie Mae Weems History And Dreams

Winter 2009 By A. M. Weaver

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Archive

-

Archive

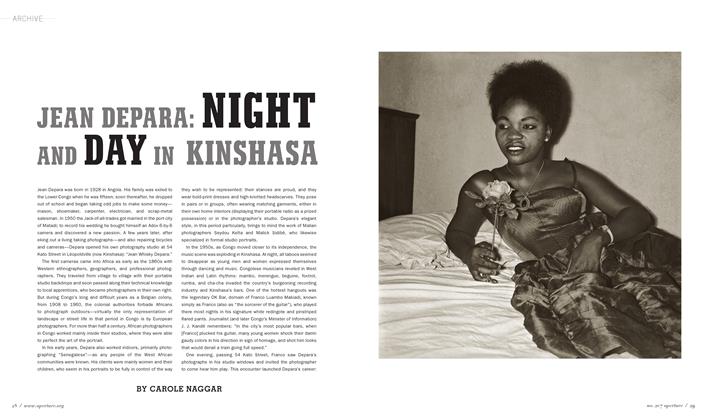

ArchiveJean Depara: Night And Day In Kinshasa

Summer 2012 By Carole Naggar -

Archive

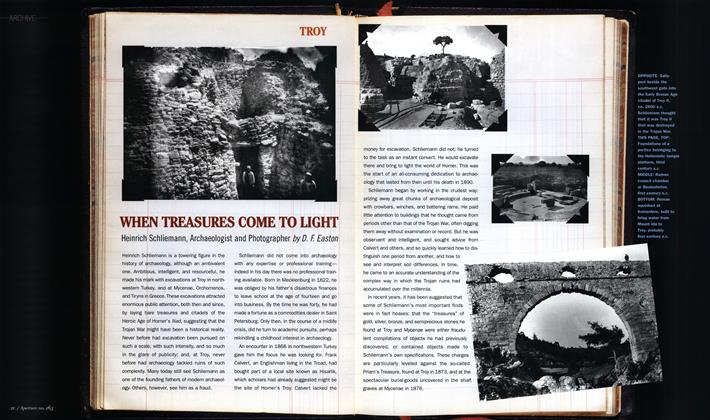

ArchiveWhen Treasures Come To Light

Spring 2001 By D. F. Easton -

Archive

Archive"Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow"

Fall 2006 By David Levi Strauss -

Archive

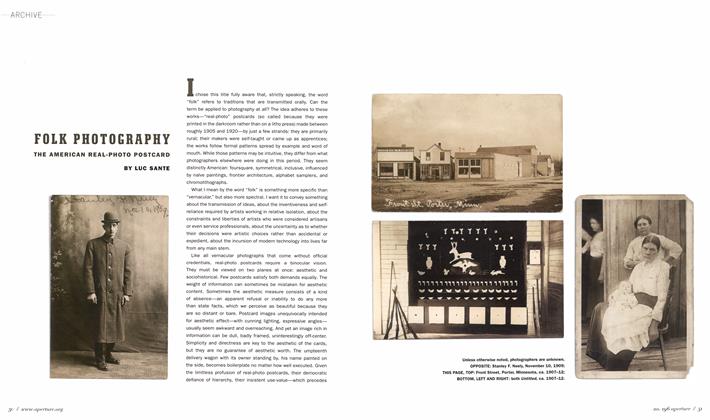

ArchiveFolk Photography The American Real-Photo Postcard

Fall 2009 By Luc Sante -

Archive

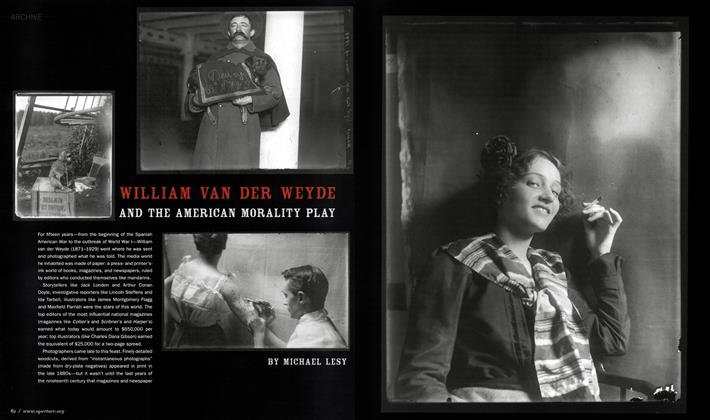

ArchiveWilliam Van Der Weyde And The American Morality Play

Spring 2009 By Michael Lesy -

Archive

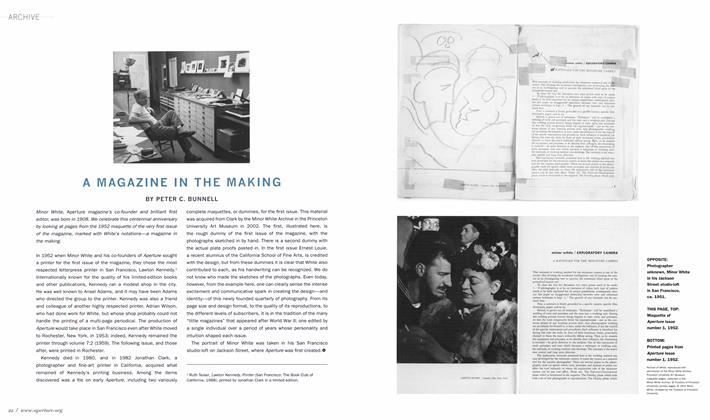

ArchiveA Magazine In The Making

Winter 2008 By Peter C. Bunnell