DANIEL AND GEO FUCHS IN THE HALLS OF THE STASI

ON LOCATION

MATTHIAS HARDER

If we were to see the interiors photographed by Daniel and Geo Fuchs without knowing what these rooms once were, we might not be deeply stirred by them. It was in these spaces that thousands of citizens of the former German Democratic Republic (GDR) were detained and brutally interrogated. Some of these detention centers were completely gutted after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989; others have been transformed into memorials to which the public has access, and where photographers and artists are now able to create images that explore the banality of evil.

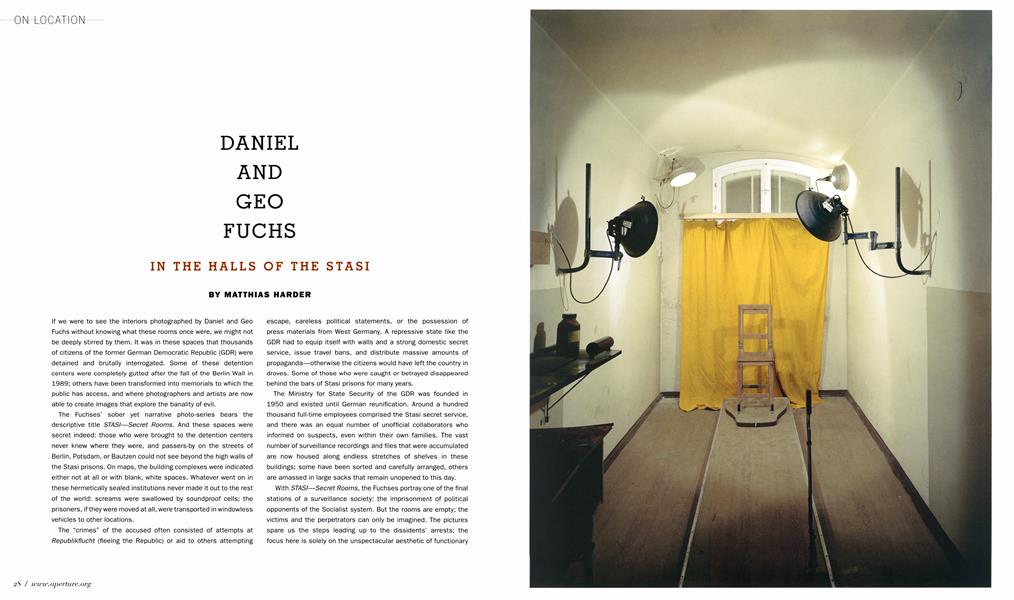

The Fuchses’ sober yet narrative photo-series bears the descriptive title STASI—Secret Rooms. And these spaces were secret indeed: those who were brought to the detention centers never knew where they were, and passers-by on the streets of Berlin, Potsdam, or Bautzen could not see beyond the high walls of the Stasi prisons. On maps, the building complexes were indicated either not at all or with blank, white spaces. Whatever went on in these hermetically sealed institutions never made it out to the rest of the world; screams were swallowed by soundproof cells; the prisoners, if they were moved at all, were transported in windowless vehicles to other locations.

The “crimes” of the accused often consisted of attempts at Republikflucht (fleeing the Republic) or aid to others attempting escape, careless political statements, or the possession of press materials from West Germany. A repressive state like the GDR had to equip itself with walls and a strong domestic secret service, issue travel bans, and distribute massive amounts of propaganda—otherwise the citizens would have left the country in droves. Some of those who were caught or betrayed disappeared behind the bars of Stasi prisons for many years.

The Ministry for State Security of the GDR was founded in 1950 and existed until German reunification. Around a hundred thousand full-time employees comprised the Stasi secret service, and there was an equal number of unofficial collaborators who informed on suspects, even within their own families. The vast number of surveillance recordings and files that were accumulated are now housed along endless stretches of shelves in these buildings; some have been sorted and carefully arranged, others are amassed in large sacks that remain unopened to this day.

With STASI—Secret Rooms, the Fuchses portray one of the final stations of a surveillance society; the imprisonment of political opponents of the Socialist system. But the rooms are empty; the victims and the perpetrators can only be imagined. The pictures spare us the steps leading up to the dissidents’ arrests; the focus here is solely on the unspectacular aesthetic of functionary 2architecture. Some of the rooms in the series can be identified as interrogation chambers—one can only imagine how many confessions were extorted here, how many spirits broken.

In other images we see, still adorning the walls, portraits of onetime powers—including Erich Honecker, who led the GDR from 1971 to 1989; Honecker’s predecessor Walter Ulbricht; and Felix Dzerzhinsky, head of the Bolshevik secret police, whose portrait is leaned up against the wall. Any zeal for revolution or Communism seems to be absent. One photograph shows the office of the State Security Minister Erich Mielke, who headed the Stasi for more than three decades. The room couldn’t be more bourgeois; one would never suspect that it was from here that Mielke controlled a vast network of spies and informants.

The Fuchses’ Berlin-based contemporaries David Adam and Marcus Flöhn were pioneers in this terrain, with similarly understated photographic works: Adam’s 1999-2000 series on the Stasi prison in Bautzen II, and Flöhn’s 1999 images of the Stasi headquarters in Berlin’s Normannenstrasse. The Fuchses, who work as a creative team, often on elaborate projects, realized this decidedly political photoseries between 2004 and 2006, when the couple received a residency grant in Berlin from the Starke Foundation. The images were first presented in Munich at the Villa Stuck, then in museums and cultural institutions in Spain, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

In this series—as in their other projects, such as Toygiants (2007)—the artists show an interest in the balance of form and content, treading a line between external appearances and the visualization of an overall notion or concept. (Flere, for example, the horror is not overtly visible—these could easily be the innocuous offices of an insurance agency rather than rooms of interrogation and torture.) What might seem at first glance to be simple documentation is actually based on careful artistic method. In each room pictured, adjustments have been made to every element within the frame to achieve the desired image. The open doors at Flohenschönhausen, in the series’s closing image, were meticulously positioned so that their angles created an ideal light for the photograph. The artists made Polaroid studies prior to using their studio camera, to ensure the perfection of the final shot.

Addinga level of conceptual complexityto these images, the rooms of the former Stasi buildings that we see have been reconstructed for contemporary visitors. Can the windowless prison cells and offices of these real, historic sites still be seen as authentic? Or has their authenticity been undermined by the interventions over time? Are the contents of the rooms merely props? Are these just approximations of places where thousands were physically and psychologically terrorized for years? Photography, the two-headed Janus, seems ideally suited to such a puzzle: its level of visual accuracy connotes a certain objectivity, and yet it continues to be used subjectively. The question of whether we have here the depiction of an "authentic" location, or only its representation, remains open.

The viewer’s experience of these interiors and their contents is quite different in the exhibition context and in publication format. In the exhibition, the confrontation with the individual photographs, presented in large format, is very immediate. In the pages of a magazine such as this, the images—grouped together and sequenced—provide a clearer narrative and demand more successive consideration. The photographs are all taken at eye level and with a centralized perspective. The Fuchses let the spaces speak for themselves. Everything seems frozen, like a film paused (though not a film still); only the people have disappeared from the scene. The Fuchses shift the narrative structure into the mind of the observer, allowing the subject to echo inside us in all its complexity and tragedy.

The rehabilitation of the East German justice (or injustice) system and its surveillance apparatus continues; the remaining Stasi files and methodically recorded wire-tapping logs are now available to the public. Even today, decades after Germany’s unification, official and unofficial Stasi informers are still being exposed—though former East German spies are seldom legally prosecuted. With this series, Daniel and Geo Fuchs have rubbed salt onto an open sore of recent German history while simultaneously contributing to its articulation and healing.©

Alisa Kotmair

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

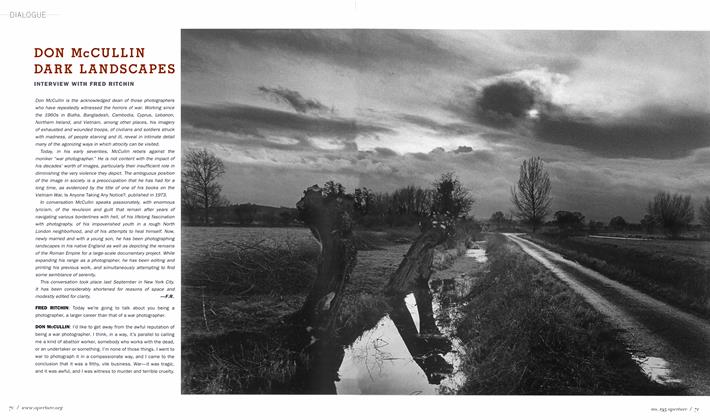

DialogueDon McCullin: Dark Landscapes

Summer 2009 By Fred Ritchin -

Theme And Variations

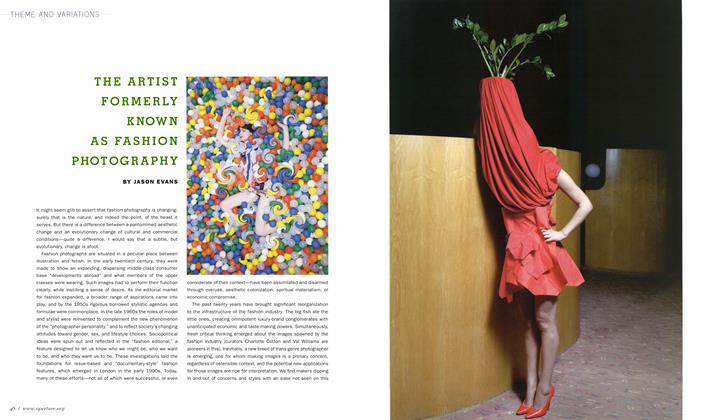

Theme And VariationsThe Artist Formerly Known As Fashion Photography

Summer 2009 By Jason Evans -

Portfolio

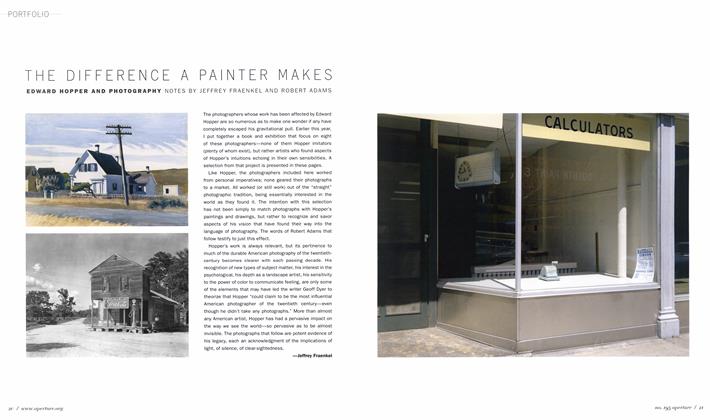

PortfolioThe Difference A Painter Makes

Summer 2009 By Jeffrey Fraenkel, Robert Adams -

Mixing The Media

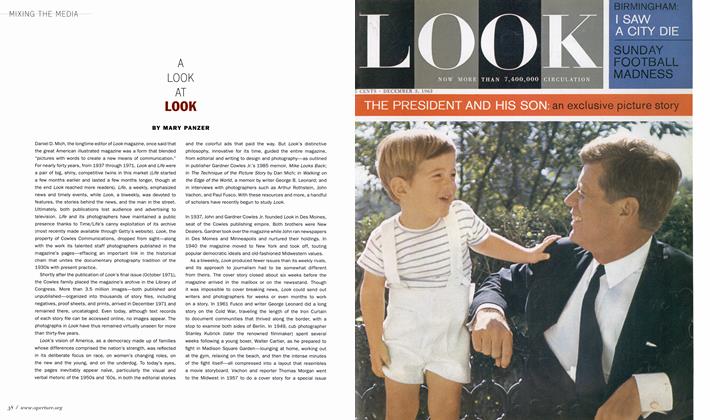

Mixing The MediaA Look At Look

Summer 2009 By Mary Panzer -

Archive

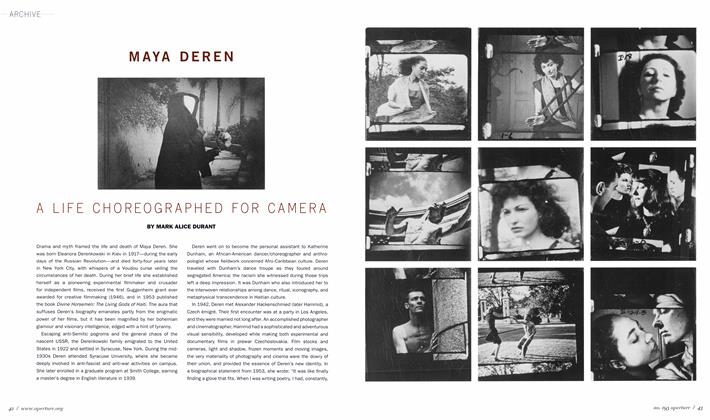

ArchiveMaya Deren

Summer 2009 By Mark Alice Durant -

Essay

EssayGay Men Play

Summer 2009 By Chris Boot

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

On Location

-

On Location

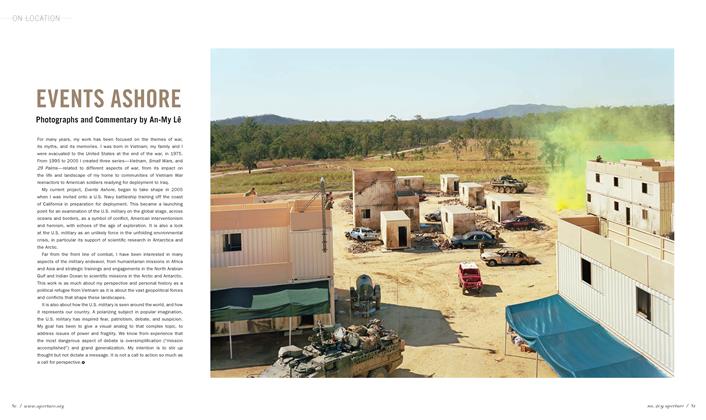

On LocationEvents Ashore

Winter 2012 By An-My Lê -

On Location

On LocationDawoud Bey's Harlem

Winter 2007 By Arthur C. Danto -

On Location

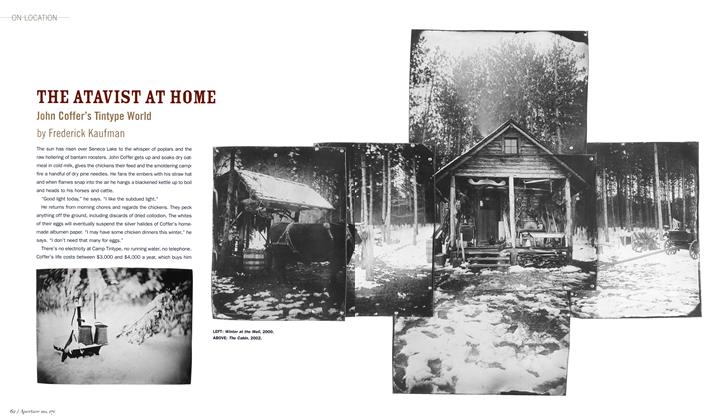

On LocationThe Atavist At Home: John Coffer's Tinytpe World

Spring 2003 By Frederick Kaufman -

On Location

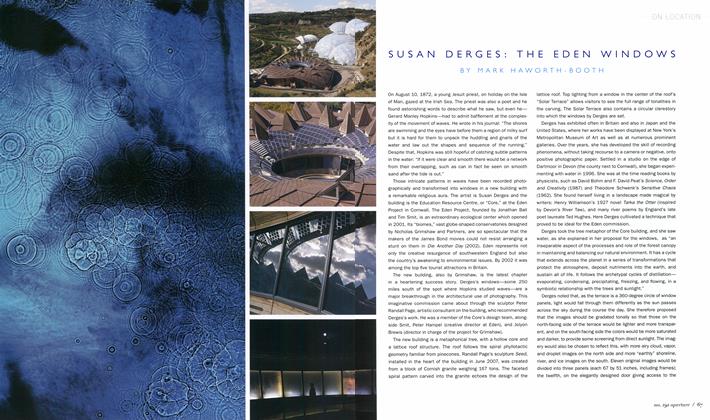

On LocationSusan Derges: The Eden Windows

Summer 2008 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

On Location

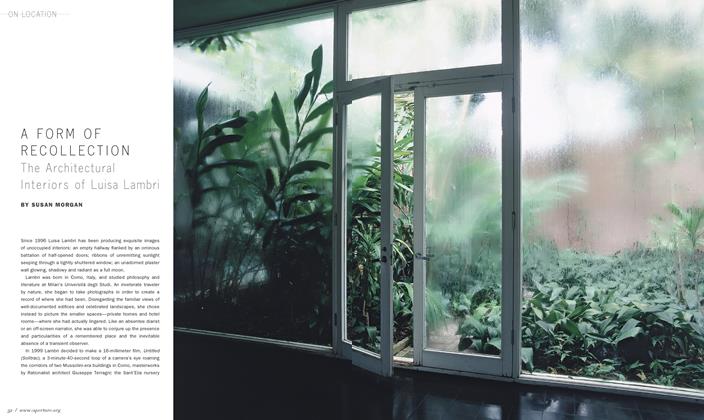

On LocationA Form Of Recollection The Architectural Interiors Of Luisa Lambri

Spring 2011 By Susan Morgan -

On Location

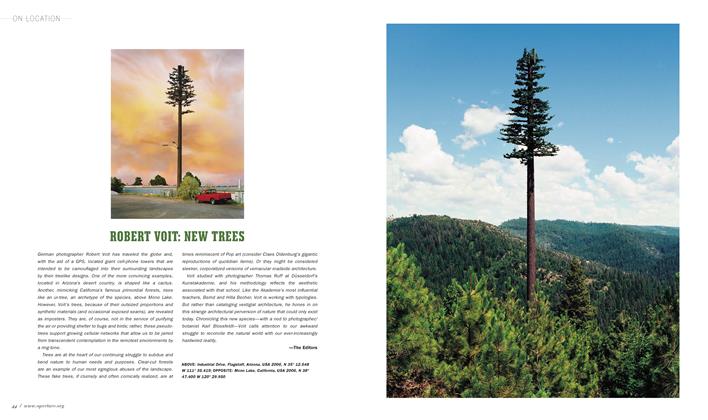

On LocationRobert Voit: New Trees

Spring 2010 By The Editors