AFGHANISTAN’S OPIUM WARS

WITNESS

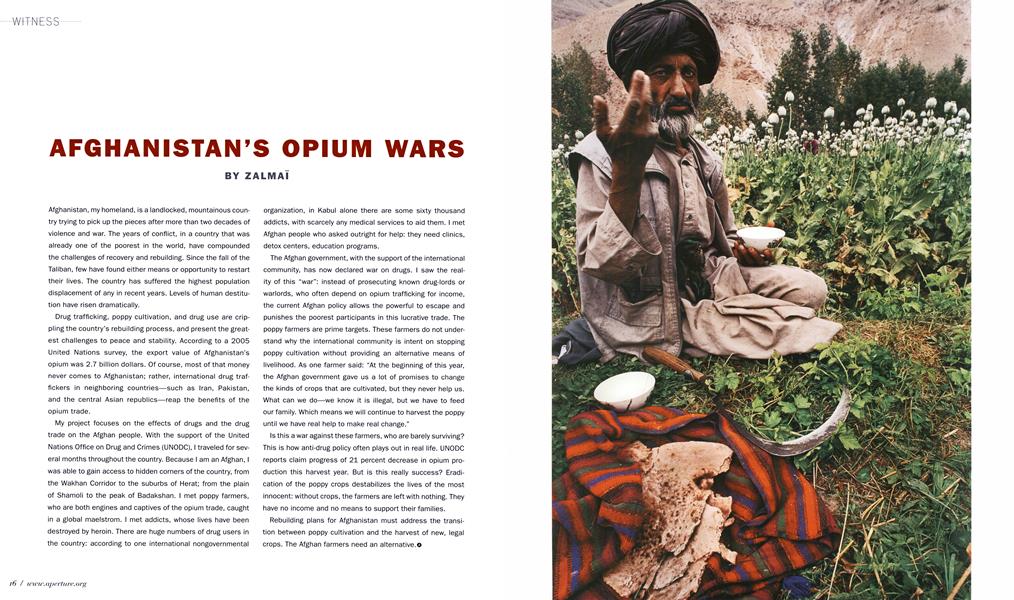

ZALMAÏ

Afghanistan, my homeland, is a landlocked, mountainous country trying to pick up the pieces after more than two decades of violence and war. The years of conflict, in a country that was already one of the poorest in the world, have compounded the challenges of recovery and rebuilding. Since the fall of the Taliban, few have found either means or opportunity to restart their lives. The country has suffered the highest population displacement of any in recent years. Levels of human destitution have risen dramatically.

Drug trafficking, poppy cultivation, and drug use are crippling the country’s rebuilding process, and present the greatest challenges to peace and stability. According to a 2005 United Nations survey, the export value of Afghanistan’s opium was 2.7 billion dollars. Of course, most of that money never comes to Afghanistan; rather, international drug traffickers in neighboring countries—such as Iran, Pakistan, and the central Asian republics—reap the benefits of the opium trade.

My project focuses on the effects of drugs and the drug trade on the Afghan people. With the support of the United Nations Office on Drug and Crimes (UNODC), I traveled for several months throughout the country. Because I am an Afghan, I was able to gain access to hidden corners of the country, from the Wakhan Corridor to the suburbs of Herat; from the plain of Shamoli to the peak of Badakshan. I met poppy farmers, who are both engines and captives of the opium trade, caught in a global maelstrom. I met addicts, whose lives have been destroyed by heroin. There are huge numbers of drug users in the country: according to one international nongovernmental organization, in Kabul alone there are some sixty thousand addicts, with scarcely any medical services to aid them. I met Afghan people who asked outright for help: they need clinics, detox centers, education programs.

The Afghan government, with the support of the international community, has now declared war on drugs. I saw the reality of this “war”: instead of prosecuting known drug-lords or warlords, who often depend on opium trafficking for income, the current Afghan policy allows the powerful to escape and punishes the poorest participants in this lucrative trade. The poppy farmers are prime targets. These farmers do not understand why the international community is intent on stopping poppy cultivation without providing an alternative means of livelihood. As one farmer said: “At the beginning of this year, the Afghan government gave us a lot of promises to change the kinds of crops that are cultivated, but they never help us. What can we do—we know it is illegal, but we have to feed our family. Which means we will continue to harvest the poppy until we have real help to make real change.”

Is this a war against these farmers, who are barely surviving? This is how anti-drug policy often plays out in real life. UNODC reports claim progress of 21 percent decrease in opium production this harvest year. But is this really success? Eradication of the poppy crops destabilizes the lives of the most innocent: without crops, the farmers are left with nothing. They have no income and no means to support their families.

Rebuilding plans for Afghanistan must address the transition between poppy cultivation and the harvest of new, legal crops. The Afghan farmers need an alternative.©

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

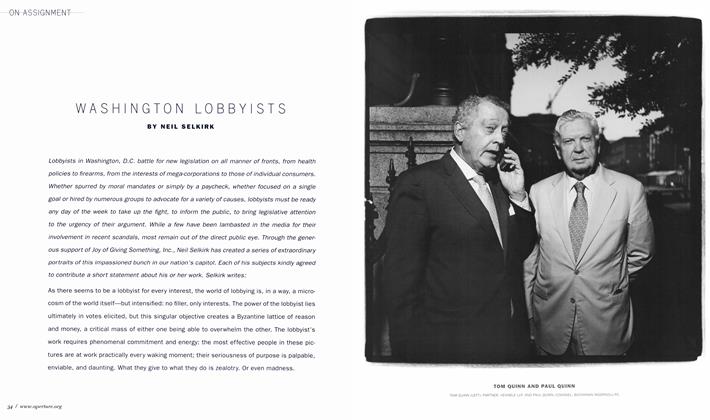

On Assignment

On AssignmentWashington Lobbyists

Fall 2006 -

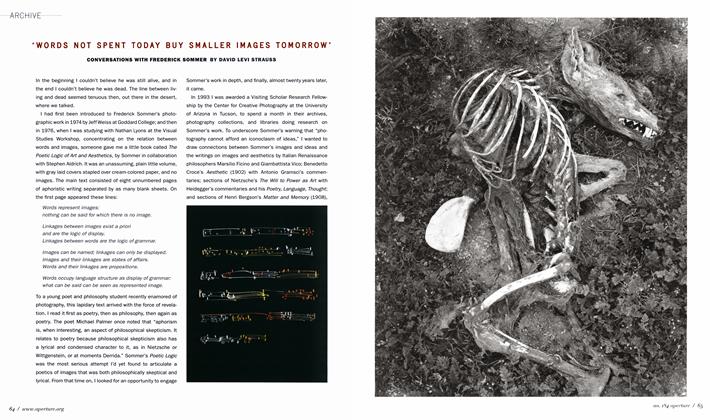

Archive

Archive"Words Not Spent Today Buy Smaller Images Tomorrow"

Fall 2006 By David Levi Strauss -

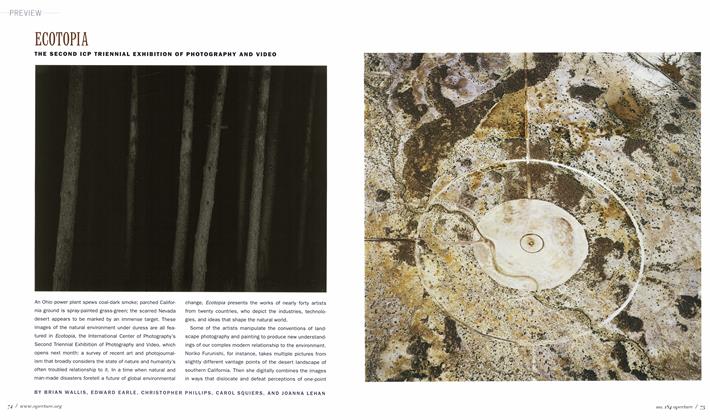

Preview

PreviewEcotopia

Fall 2006 By Brian Wallis, Edward Earle, Christopher Phillips2 more ... -

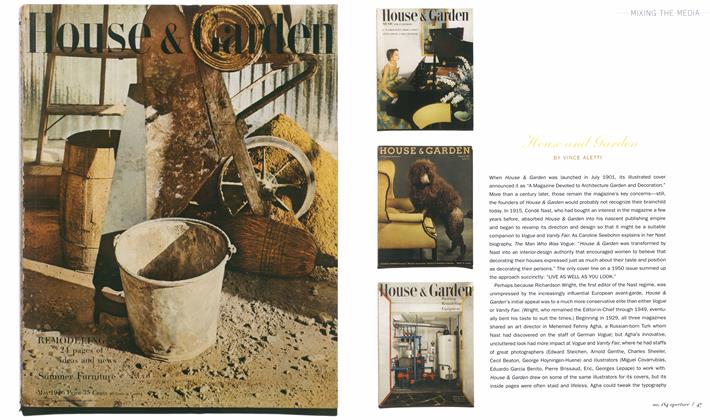

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaHouse And Garden

Fall 2006 By Vince Aletti -

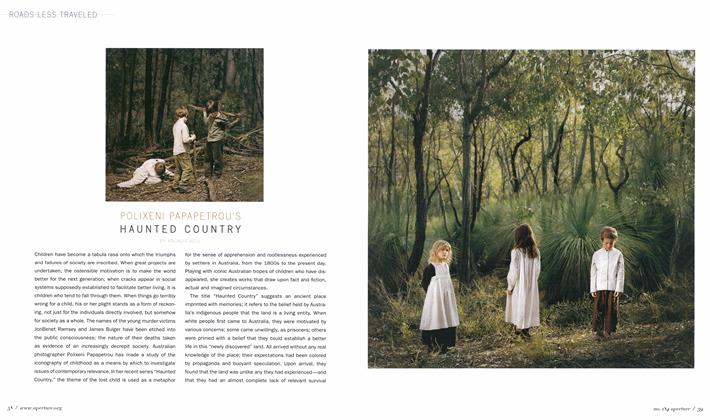

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledPolixeni Papapetrou’s Haunted Country

Fall 2006 By Anonda Bell -

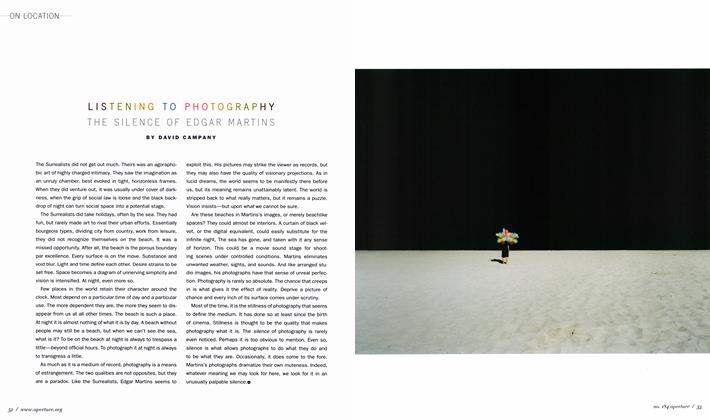

On Location

On LocationListening To Photography The Silence Of Edgar Martins

Fall 2006 By David Campany

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Witness

-

Witness

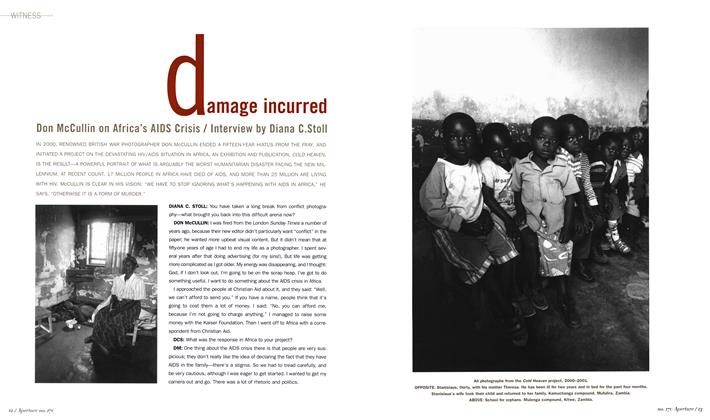

WitnessDamage Incurred: Don McCullin On Africa's Aids Crisis

Spring 2003 By Diana C.Stoll -

Witness

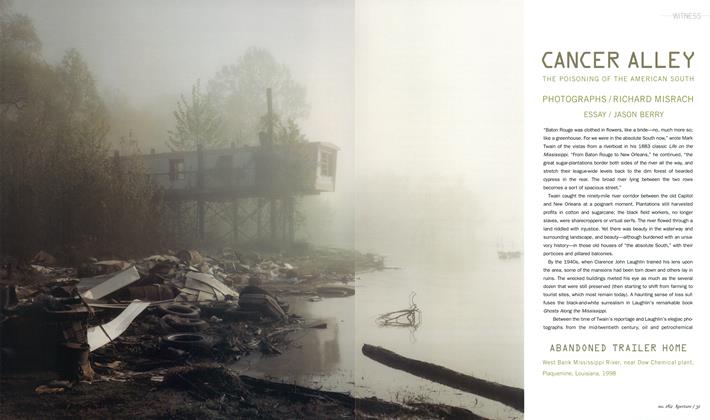

WitnessCancer Alley

Winter 2001 By Jason Berry -

Witness

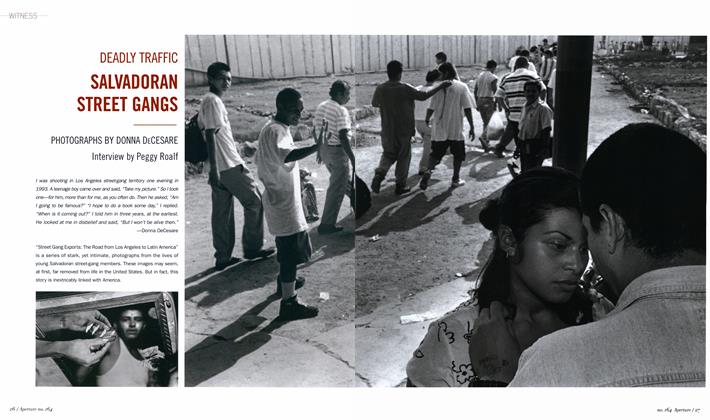

WitnessDeadly Traffic Salvadoran Street Gangs

Summer 2001 By Peggy Roalf -

Witness

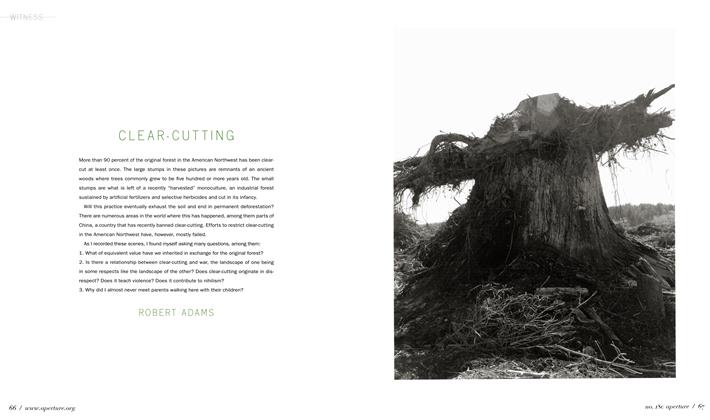

WitnessClear-Cutting

Fall 2005 By Robert Adams -

Witness

WitnessImages Of The Everywhere War

Winter 2012 By Trevor Paglen -

Witness

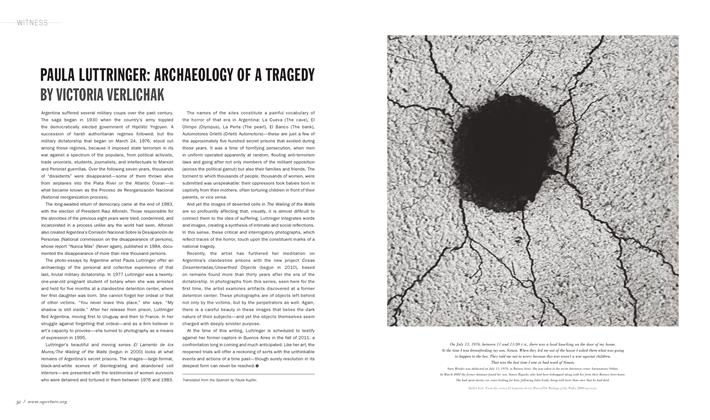

WitnessPaula Luttringer: Archaeology Of A Tragedy

Spring 2012 By Victoria Verlichak