DONNA FERRATO ON LIBIDO ROAD

PROFILE

CLAUDIA GLENN DOWLING

We are in a nice suburban house in a nice suburban neighborhood with a nice hostess, Lynn, a forty-six-year-old woman who is putting salsa and chips out, lighting candles, arranging flowers, and doing all the things hostesses do as they prepare for an evening with friends. She is also setting out stacks of towels and bouquets of toothbrushes and moving around several inflatable mattresses that blow up quickly for overnight guests. Her husband, John, pens up the dogs and pops a quarter-tab of Viagra.

An hour later, our nice hostess is lying in a pile of bodies in front of the fireplace, with a man’s head in her crotch, as another woman straddles the host. It is a night of group sex. And Donna Ferrato is photographing the action.

Donna has been documenting swingers since the late 1970s, when the cultural phenomenon erupted into public consciousness along with New York City’s infamous free-sex club, Plato’s Retreat. She was there, with her camera. Over the years, she has watched the evolution of this subculture, from its initial exuberant heyday, through a decade or so of AIDS-induced Puritanism that closed the doors of many swing clubs, to its current resurgence—complete with “polyamory workshops” at annual swingers’ conventions attracting thousands of attendees. It is a world that fascinates Donna, and she sees the free expression of sexuality as a positive development, particularly for women, who are often the sexual aggressors in the world of swingers. “Year after year,” she says, “I have witnessed how these people can grow stronger as they become more loving, tolerant, and honest with one another, without ever hurting anyone.”

It’s not easy to get into an orgy as a journalist—let alone to take pictures and get people to sign releases—but somehow, using a mixture of seduction and refusal to accept rejection, Donna has managed it, again and again, for nearly three decades. She has had some trouble convincing the writers she has occasionally hauled along to join her in follow-up stones. Generally, Donna prefers to work with other females, since men, she claims, have more of a tendency to jump into the action. “You do this long enough, you want to get into the swing of things,” she notes. But the females, while usually nonparticipatory, have a tendency to come down with odd ailments while they’re on the stories—such as boils or hives in the eyes ... or they simply can’t take it.

The line between journalism and voyeurism is thin, but for some reason, watching people have sex is considered prurient while watching them get killed is not. The word pornography becomes an epithet for visual coverage of an activity at least as basic to humankind as eating, and probably more so. Donna is a self-professed crusader, on a mission to draw back the curtains and let in the light.

She is better known for her parallel crusade to expose the dark side of sex and love: the horrors of domestic violence. It is this body of work (much of it collected in Aperture’s book Living With the Enemy), along with her establishment of the nonprofit Domestic Abuse Awareness Project, that helped to earn Donna the W. Eugene Smith Grant and, in 2002, the prestigious Distinguished Honor Award for Service in Journalism from the University of Missouri.

So it is easy to understand why Donna is also driven to cover “happy” love and sex, in a way that gives women a chance at the upper hand, rather than rendering them as victims. Her work with swingers depicts a vision, as she puts it, of “healthy, true love and passion that can exist between couples ... a counterbalance to the dark, painful side of relationships.”

Donna is the only photographer who has ever been welcomed into the swingers’ community without herself being a swinger. Over the decades, she has developed a relationship of trust with hundreds of people in what is essentially a closed circle. Swingers use the same terminology that gays often use, referring to the “straight” world and to being “out.” (Most swingers are otherwise conventional people, with kids and jobs as schoolteachers and policemen, and they are definitely not “out.”)

Lynn and her husband feel comfortable with Donna’s genuine enthusiasm, but they sense my reservations about what they call their “lifestyle.” Lynn is chief paramedic for her town; John is a squid fisherman. We are asking them to out themselves, on national TV no less, for our documentary series on Oxygen, Sex Lives on Videotape. John talks about one-way mirrors and how unfair it is that he’s always on one side and we’re always on the other. He has a point: I am always staggered by the way people give themselves over to journalists. But there is some return. When subjects look into that mirror held up by the journalist, it can change the way they see themselves, and change their lives—sometimes for the better, but not always. As a direct result of our television documentary, marriages will be destabilized, one woman will lose the lease on her house, and Lynn will be fired from her job. John and Lynn, however, will say that we simply speeded up the inevitable and will be generous enough not to blame Donna and me.

One night, as we work on our story, Donna and I are in a swing club for a massive orgy. The swing rooms have foam mattresses covered with velour and swagged with golden tassels. There are bowls of condoms and bottles of lubricant distributed about. There are side rooms with a variety of implements, themes, accoutrements, and “rules,” and there are people in each of these rooms, going at it in all manners and combinations.

The couples by the bar where I sit look conventional enough— the women perhaps slightly overcostumed, In slit skirts and stiletto heels and deep décolletage, but nothing truly outrageous. They look like what they are: suburban matrons with an odd kick in their gallop. The men look like any guys you might see sitting behind a desk. Then someone nudges my shoulder and I look over. At the next barstool, a woman is being held by her husband as another woman goes down on her, and her husband sucks her breast. Donna, of course, is taking pictures.

Donna shoots from the hip, or the shoulder, or over her head, or behind her back. She holds her camera casually, as if she’s about to drop it. She talks to people more than she photographs them. She is curious, sympathetic, entranced. And she has hair-trigger reflexes that allow her to see a moment coming and swing a camera into place to catch an interaction that no one else could even recognize until they see it in the printed frame. She’s raw and rough and real. No fear, no holding back; up close and personal. John has got Donna figured already: “Her camera is her sex organ.”

Soon enough, though, John tells Donna she can’t shoot anymore tonight. Coitus interruptus. I am disappointed: did we come to this power orgy for nothing? Donna teases me. “Relax,” she says. “We can’t shoot. So what? Aren’t you glad you’re here?” She doesn’t find these experiments in new forms of marriage and sexuality shocking or perverse. She feels that here women and men can exercise their sexual freedom frankly and openly, a privilege historically enjoyed by men only. “What’s wrong with it?” she asks. “These people are not cheating. They’re honest.”

With half of all American couples divorcing, it seems pretty obvious that something about traditional monogamous marriage may not be working. “In the U.S., we’re all individuals,” explains Robert McGinley, the founder of Lifestyles, a swingers’ organization that has been around for three decades and has attracted tens of thousands of members all over the country. “You can sublimate yourself for a while, but then the desires surface.” Donna puts it more simply: “You get bored with each other sexually.” Despite the fact that she is herself recently married, Donna claims she’s not good wife material. “At least these people are trying something different,” she says.

Most swingers have the same problems everyone else does, of course, including jealousy. They claim to have untwisted the strands of love and sex, and indeed, having sex with other people may not make some couples jealous. But if someone sees his or her mate whispering in an ear, kissing or seeking out the same person again and again for sex, it’s threatening. It’s intimacy that is the threat, not the sex per se. Says McGinley: “Dayto-day living is far more difficult than having a sex date.”

Donna and I both wonder why there is apparently no AIDS in the swinging population. Not one case has been reported, McGinley claims. But we see plenty of people who don’t use condoms, and we can’t help asking ourselves about the incidence of other sexually transmitted diseases. Lynn says that the worst thing they’ve ever given to others in her group is strep throat.

There are “hard swingers”—those who have sex with multiple people they don’t know—and “soft swingers,” who tend to do straightforward swapping among couples. “I don’t think I could ever be a hard swinger,” says Donna. “I’d be too worried about getting diseases. I don’t want to have sex with strangers.” This realization comes after twenty-five years of flirting with the notion through photography. Still, Donna’s images of this world do reveal what looks like real joy in the faces of its denizens. For many of us who don’t live there, it’s hard to look at these pictures and not wonder: “Well, why not?”

After all, how private was sex back when we were all tribal? Not very, in that cave or group hut. I think Donna may have a point about widening our sexual parameters. Our culture is hypocritical in so many ways. Sex is used to sell products and get jobs and find mates, but it’s rarely addressed in a direct and playful way. People need to talk more openly about marriage and monogamy and desire and pleasure. After my work with Donna, it is hard to be shocked by the things people get up to sexually, and I can now talk about all kinds of acts without blushing. But for me—as for many others—sex with one person is confusing enough. I may prefer to withdraw to the privacy of my own cave with someone I love as well as desire, but what I do there . . . well, let’s just say that my lover wants to send Donna flowers. And if Donna’s crusade succeeds, and love and sex come to be openly discussed in our society, we may all want to go in on a great big, fecund, fragrant bouquet. ©

Donna Ferrato's book Love & Li/siwill be published by Aperture in Spring 2004.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Work And Process

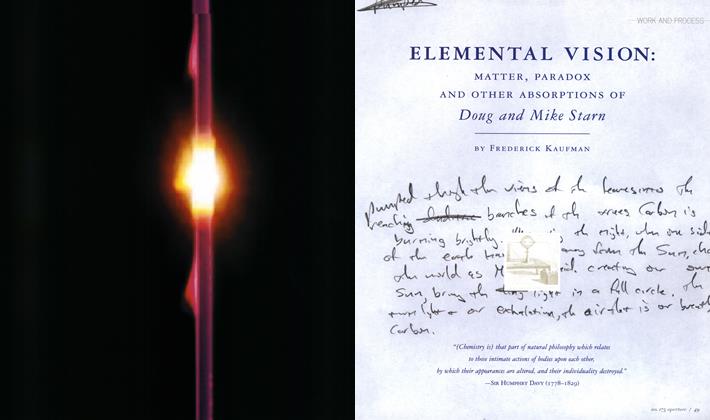

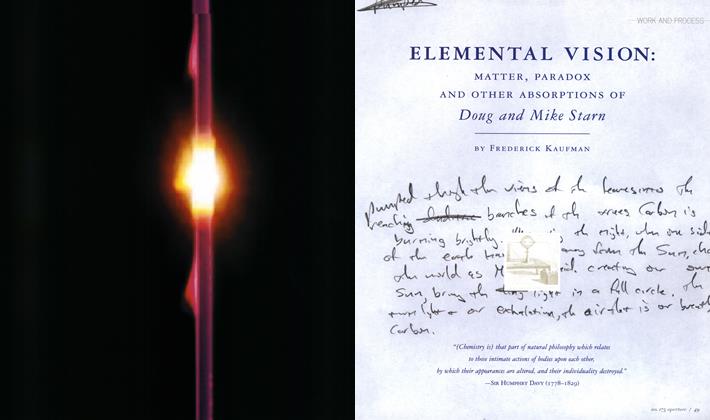

Work And ProcessElemental Vision: Matter, Paradox And Other Absorptions Of Doug And Mike Starn

Summer 2004 By Frederick Kaufman -

On Location

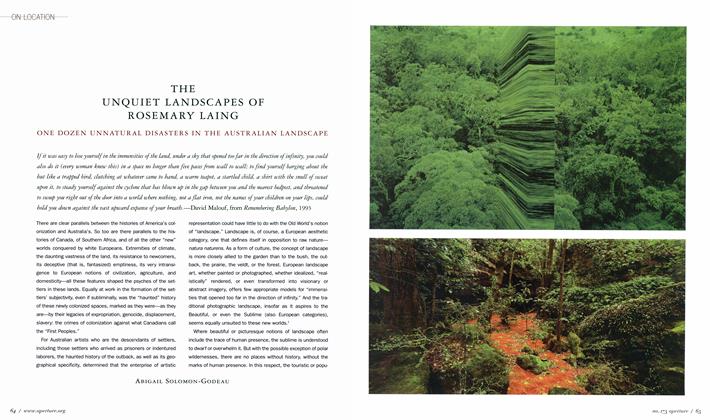

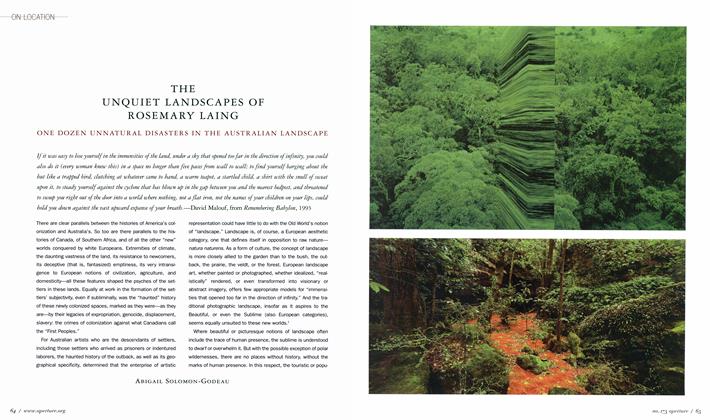

On LocationThe Unquiet Landscapes Of Rosemary Laing

Summer 2004 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau -

Roads Less Traveled

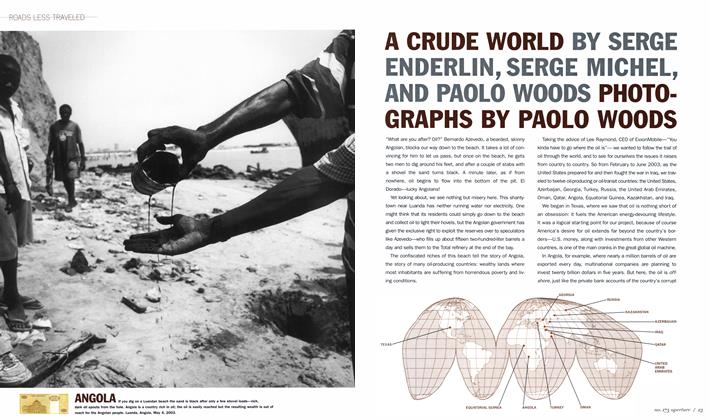

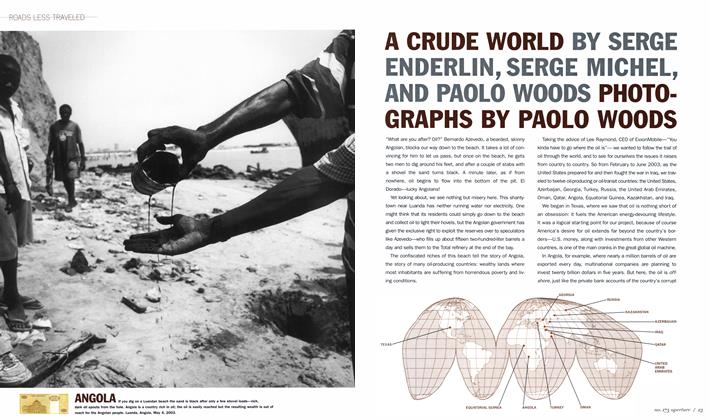

Roads Less TraveledA Crude World

Summer 2004 By Serge Enderlin, Serge Michel, Paolo Woods -

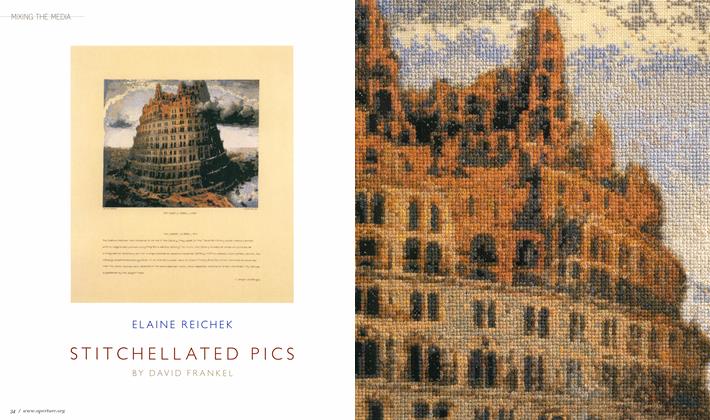

Mixing The Media

Mixing The MediaElaine Reichek Stitchellated Pics

Summer 2004 By David Frankel -

Meetings

Meetings10 Years: From Analog To Digital: Zonezero

Summer 2004 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Notes

NotesNotes

Summer 2004

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Profile

-

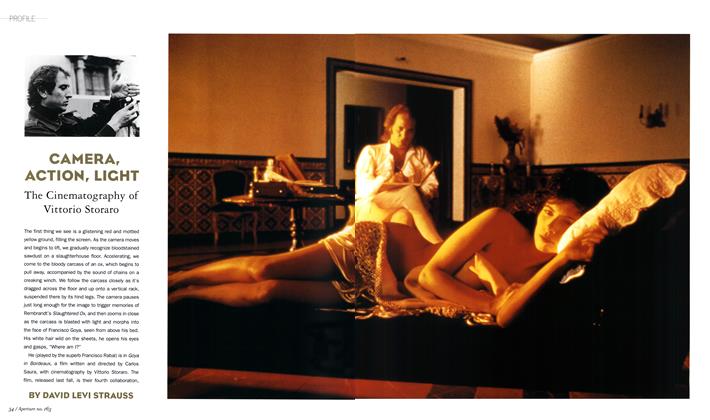

Profile

ProfileCamera, Action, Light

Spring 2001 By David Levi Strauss -

Profile

ProfileA World Out Of Balance Necessary Truths

Summer 2000 By Diana C. Stoll -

Profile

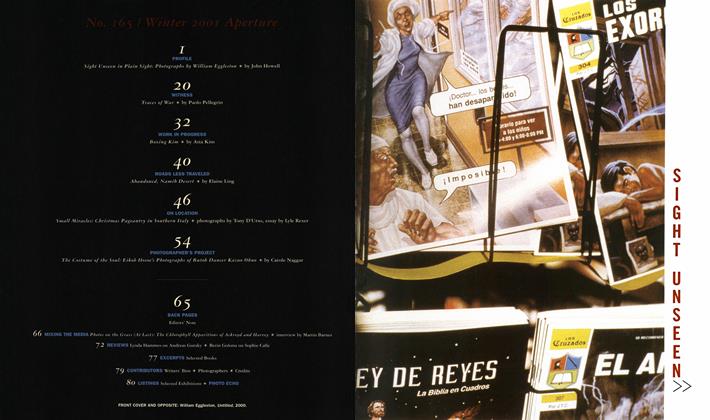

ProfileSight Unseen In Plain Sight

Winter 2001 By John Howell -

Profile

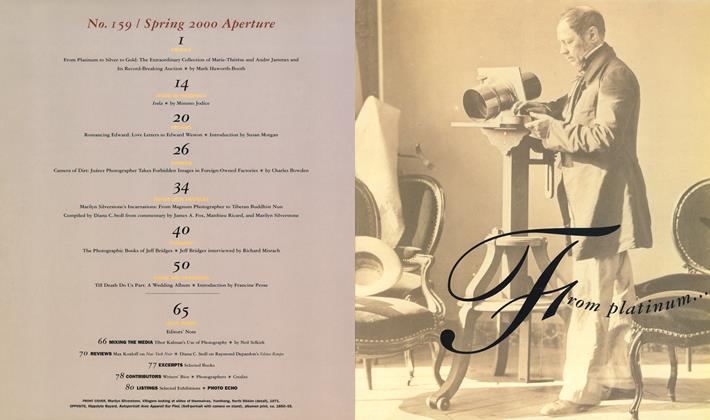

ProfileFrom Platinum...To Silver To Gold

Spring 2000 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

Profile

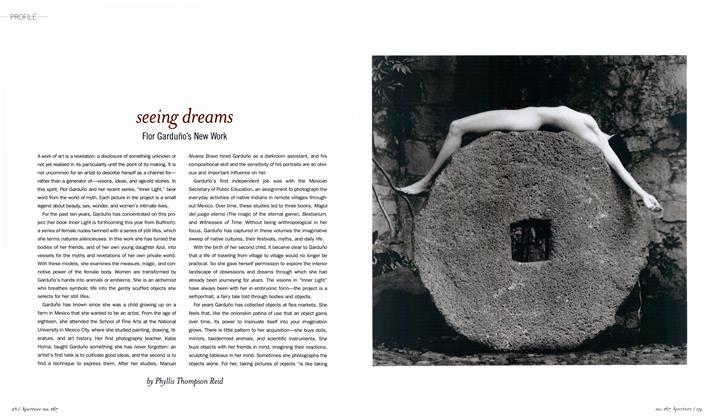

ProfileSeeing Dreams

Summer 2002 By Phyllis Thompson Reid -

Profile

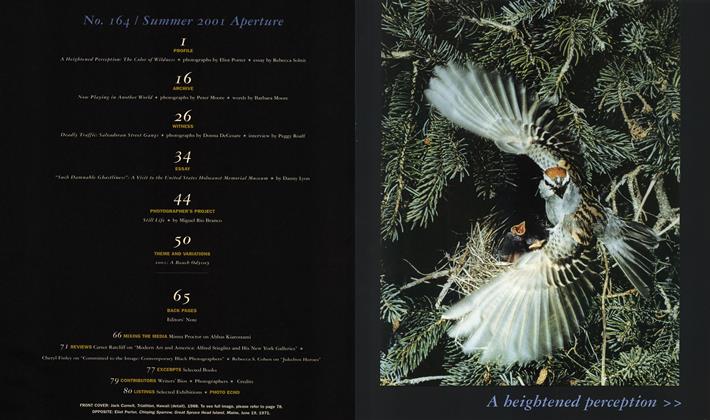

ProfileA Heightened Perception

Summer 2001 By Rebecca Solnit

More From This Issue

-

Work And Process

Work And ProcessElemental Vision: Matter, Paradox And Other Absorptions Of Doug And Mike Starn

Summer 2004 By Frederick Kaufman -

On Location

On LocationThe Unquiet Landscapes Of Rosemary Laing

Summer 2004 By Abigail Solomon-Godeau -

Roads Less Traveled

Roads Less TraveledA Crude World

Summer 2004 By Serge Enderlin, Serge Michel, Paolo Woods