The whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind. —Ralph Waldo Emerson, from “Nature,” 1836

POSTNATURAL

BILL McKIBBEN

What on earth are we looking at when we look at nature? Something separate from us, something removed? Or something of which we’re a part? That is the original paradox for our species, a question that's been in the back of our collective mind since our earliest ancestors climbed down from the trees and began the process of confusing our relationship with everything else.

But now, in our lifetimes, this cliché of the millennia has taken on an unexpected new valence, an urgency. In the last few decades we’ve grown large enough as a species that something deep has changed. The possibility of this deep change dates from the atom bomb, I suppose—all of a sudden we were big enough to kill off ourselves and nature. We’ve backed away from that brink, thank God, but it turns out there are other thresholds. For instance, our profligate use of fossil fuel has by now altered the earth’s atmosphere. Each square meter of the globe’s surface now receives an additional two watts of solar energy. That doesn’t sound like much, but it’s enough to change everything. Data published in the last eighteen months shows that severe storms occur 20 percent more often than they did a century ago, that spring comes a week earlier to the northern hemisphere, that alpine glaciers and arctic permafrost are steadily melting.

And it’s not just global warming. We’ve used so much nitrogen for fertilizer that we’ve altered the basic nutrient balance of rivers and bays. We wipe out hundreds of species a month. This is not the normal and unavoidable “pollution” that comes from altering the places where we live and grow our food. This is total. In a special issue of Science magazine last summer, four highly regarded researchers, including the president of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science, declared that we now lived on a “human-dominated” planet. This is new. We have ended nature.

And by ending nature we’ve answered in some way that original paradox. We are very much a part of nature—but no longer a subsidiary part like every other creature. We are everywhere. Every cubic meter of air carries our autograph—the telltale accumulation of carbon dioxide from the engines of our cars, the smokestacks of our factories, the combustion of our forests. An alien astronomer, by analyzing our changing

atmosphere, would be able to gauge how much we consume. We set the level of the ocean by the size of our economies, the length of the seasons by how carelessly we live. If we wise up we can still limit our damage. But we’ve stumbled blindly across some perceptual boundary, and the world will never look the same to us as it once did. We show up in every frame now, carving our initials in the trunk of every redwood, painting the names of our fraternities on every Sierra cliff.

Oddly, though, we now enter a period when the forces of the natural world will matter more to us than they ever have before. Though every year of our history as a species has been marked—one place or another—by drought, flood, hurricane, fire, earthquake, volcano, our planet as a whole has been remarkably stable overall. Our civilization has been built on that physical stability; that lack of variation has allowed us to harvest, to build, to plan with a confidence so basic it goes unspoken.

Now that confidence will be shaken. By disturbing our climate, we alter every terrestrial force: wind speed, evaporation, rainfall. The world is becoming less reliable, more variable. And that will eventually alter our perception of nature. As it gets scarier (733 people died in one Chicago heat wave two summers ago), it will be easy to retreat to a view of nature as enemy and adversary. And as we come to see just how profoundly our greed and folly have shaped the world around us, it will be easy to concoct a postmodern, distanced sense of nature.

What we need instead is an unblinking willingness to confront painful reality, to locate us in our actual—tragic—relation to the earth. To do so would require understanding just how beautiful the earth still is, how gorgeous it remains even in its defaced state. And from that we need to construct a new art that would help us understand what it means to be human now. This century, unfortunately, has already forced such reconstructions on us—the Holocaust and AIDS are poignant and tragic examples. New ways of seeing have helped us, at least a little, to continue living amidst great sadness.

And this new way of seeing people and nature must help us in our doing as well, must help us to more than imagine what it might be like to take up less space, to reduce our dominion. The relation of the human and the natural is now both the key practical and the key aesthetic or moral question of our day. ■

In the morning I found, to my disgust, that the camp was to retain its position for another day.

I dreaded its languor and monotony, and to escape it, I set out to explore the surrounding mountains. . . . After advancing for some time ... I saw at some distance the black head and red shoulders of an Indian among the bushes above. . . . Looking for a while at the old man, I was satisfied that he was engaged in an act of worship, or prayer, or communion of some kind with

a supernatural being. . . . He has a guardian spirit, on whom he relies for succor and guidance. To him all nature is instinct with mystic influence. Among those mountains not a wild beast was prowling, a bird singing, or a leaf fluttering, that might not tend to direct his destiny, or give warning of what was in store for him; and he watches the world of nature around him as the astrologer watches the stars. -Francis Parkman, from The Oregon Trail, 1849

My spirits infallibly rise in proportion to outward dreariness. Give me the ocean, the desert, or the wilderness! When I would recreate myself, I seek the darkest wood, the thickest and most interminable and, to the citizen, most dismal swamp. I enter a swamp as a sacred place, a sanctum sanctorum. There is the strength, the marrow, of Nature.

Henry David Thoreau

No sheltering pine or mountain distance of up-piled Sierras guards the approach to the Shoshone.

You ride upon a waste—the pale earth stretched in desolation. Suddenly you stand upon a brink, as if the earth had yawned. Black walls flank the abyss. Deep in the bed a great river fights its way through labyrinths of blackened ruins, and plunges in foaming whiteness over a cliff of lava. You turn from the brink as from a frightful glimpse of the Inferno, and when you have gone a mile the earth seems to have closed again; every trace of canon has vanished, and the stillness of the desert reigns.

—Clarence King, from Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada, 1872

Here was a poem he knew . . . but it wasn’t a poem, it was a song. His mother sang it often, working at the sewing machine in winter. ... As he sang the trace grew on him again, he lost himself entirely. The bright hard dividing lines between senses blurred,

and buttercups, smell of primrose, feel of hard gravel under body and elbows, sight of the ghosts of mountains haunting the southern horizon, were one intensely felt experience focused by the song the book had evoked.—Wallace Stegner, from Big Rock Candy Mountain

Perhaps it is necessary for me to try these places, perhaps it is my destiny to know the world. It only excites the outside of me. The inside it leaves more isolated and stoic than ever. That's how it is. It is all a form of running away from oneself and the great problems: all this wild west. -D. H. Lawrence, from a letter written to Catherine Carowell

Lifting bis bead, be saw bow tbe prairie beyond tbe fireguard looked darker than in dry times, bealtbier with green-brown tints, smaller and more intimate somehow than it did when tbe heat waves crawled over scorched grass and carried tbe horizons backward into dim and unseeable distances. And standing in tbe yard above bis one clean footprint, feeling bis own verticality in all that spread of horizontal land, he sensed that as tbe prairie shrank he grew. He was immense, A little jump would crack his bead on tbe sky; a stride would take him to any horizon.

—Wallace Stegner, from Big Rock Candy Mountain

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

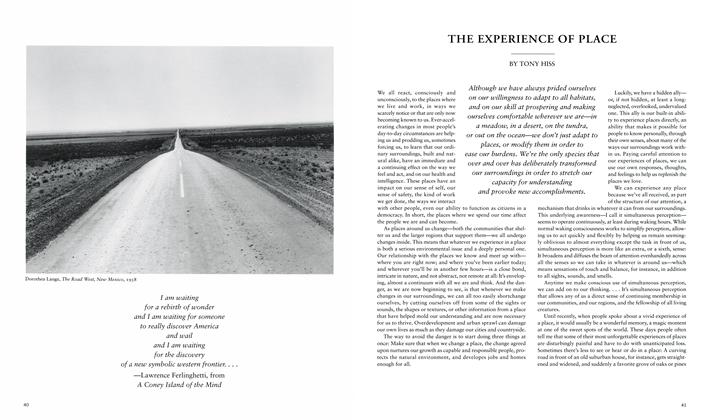

The Experience Of Place

Winter 1998 By Tony Hiss -

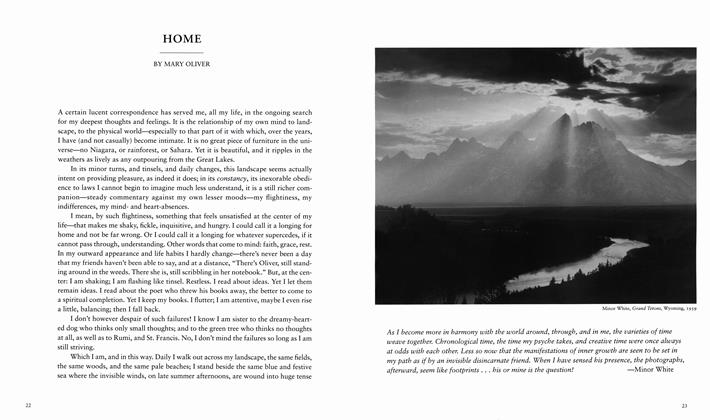

Home

Winter 1998 By Mary Oliver -

Outside (but Not Necessarily Beyond) The Landscape

Winter 1998 By Lucy R. Lippard -

People And Ideas

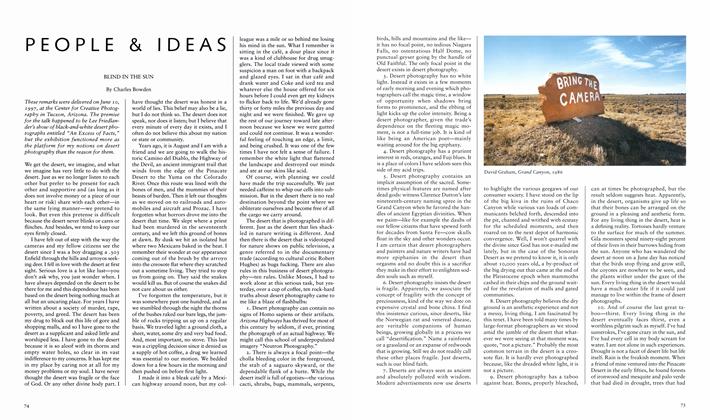

People And IdeasBlind In The Sun

Winter 1998 By Charles Bowden -

People And Ideas

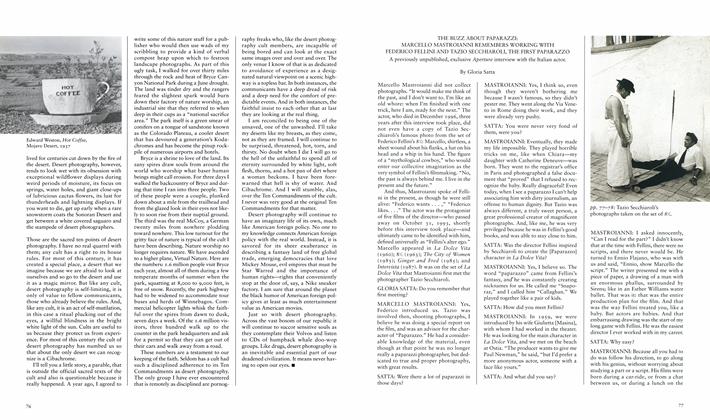

People And IdeasThe Buzz About Paparazzi: Marcello Mastroianni Remembers Working With Federico Fellini And Tazio Secchiaroli, The First Paparazzo

Winter 1998 By Gloria Satta -

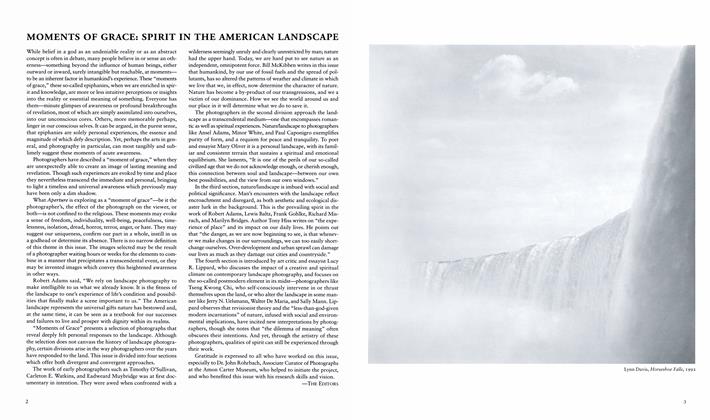

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteMoments Of Grace: Spirit In The American Landscape

Winter 1998 By The Editors