MOMENTS OF GRACE: SPIRIT IN THE AMERICAN LANDSCAPE

Editor's Note

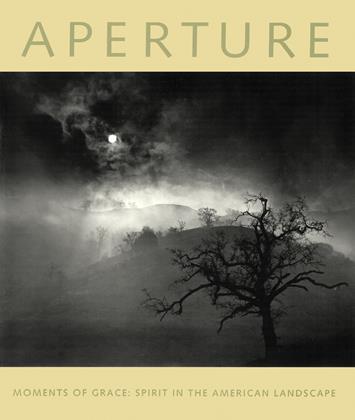

While belief in a god as an undeniable reality or as an abstract concept is often in debate, many people believe in or sense an otherness—something beyond the influence of human beings, either outward or inward, surely intangible but reachable, at moments— to be an inherent factor in humankind's experience. These “moments of grace,” these so-called epiphanies, when we are enriched in spirit and knowledge, are more or less intuitive perceptions or insights into the reality or essential meaning of something. Everyone has them—minute glimpses of awareness or profound breakthroughs of revelation, most of which are simply assimilated into ourselves, into our unconscious cores. Others, more memorable perhaps, linger in our conscious selves. It can be argued, in the purest sense, that epiphanies are solely personal experiences, the essence and magnitude of which defy description. Yet, perhaps the arts in general, and photography in particular, can most tangibly and sublimely suggest these moments of acute awareness.

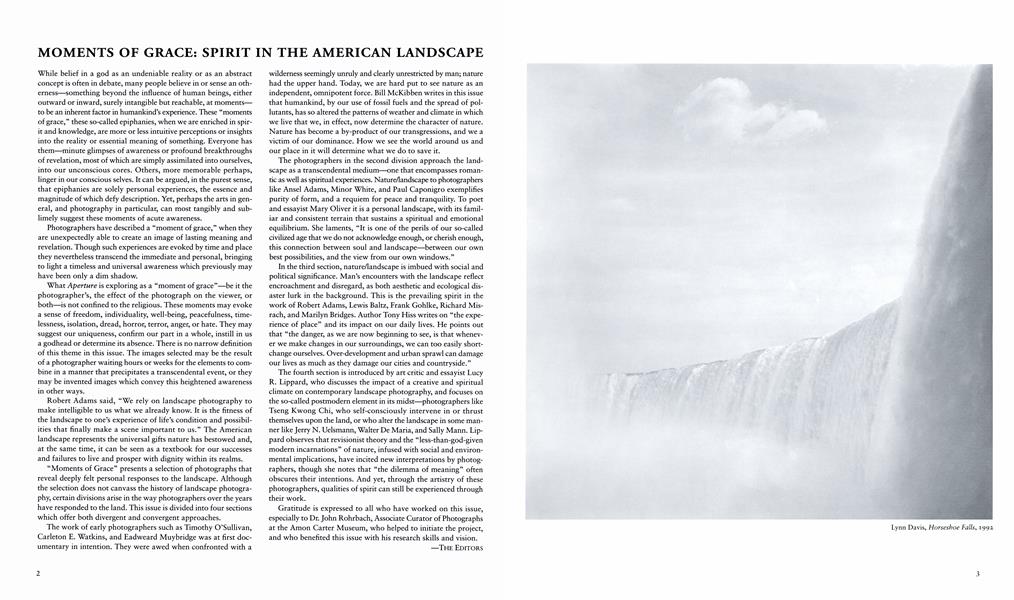

Photographers have described a “moment of grace,” when they are unexpectedly able to create an image of lasting meaning and revelation. Though such experiences are evoked by time and place they nevertheless transcend the immediate and personal, bringing to light a timeless and universal awareness which previously may have been only a dim shadow.

What Aperture is exploring as a “moment of grace”—be it the photographer’s, the effect of the photograph on the viewer, or both—is not confined to the religious. These moments may evoke a sense of freedom, individuality, well-being, peacefulness, timelessness, isolation, dread, horror, terror, anger, or hate. They may suggest our uniqueness, confirm our part in a whole, instill in us a godhead or determine its absence. There is no narrow definition of this theme in this issue. The images selected may be the result of a photographer waiting hours or weeks for the elements to combine in a manner that precipitates a transcendental event, or they may be invented images which convey this heightened awareness in other ways.

Robert Adams said, “We rely on landscape photography to make intelligible to us what we already know. It is the fitness of the landscape to one’s experience of life’s condition and possibilities that finally make a scene important to us.” The American landscape represents the universal gifts nature has bestowed and, at the same time, it can be seen as a textbook for our successes and failures to live and prosper with dignity within its realms.

“Moments of Grace” presents a selection of photographs that reveal deeply felt personal responses to the landscape. Although the selection does not canvass the history of landscape photography, certain divisions arise in the way photographers over the years have responded to the land. This issue is divided into four sections which offer both divergent and convergent approaches.

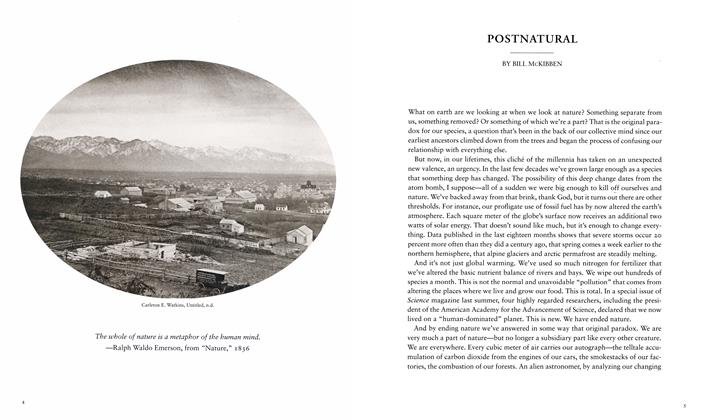

The work of early photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan, Carleton E. Watkins, and Eadweard Muybridge was at first documentary in intention. They were awed when confronted with a

wilderness seemingly unruly and clearly unrestricted by man; nature had the upper hand. Today, we are hard put to see nature as an independent, omnipotent force. Bill McKibben writes in this issue that humankind, by our use of fossil fuels and the spread of pollutants, has so altered the patterns of weather and climate in which we live that we, in effect, now determine the character of nature. Nature has become a by-product of our transgressions, and we a victim of our dominance. How we see the world around us and our place in it will determine what we do to save it.

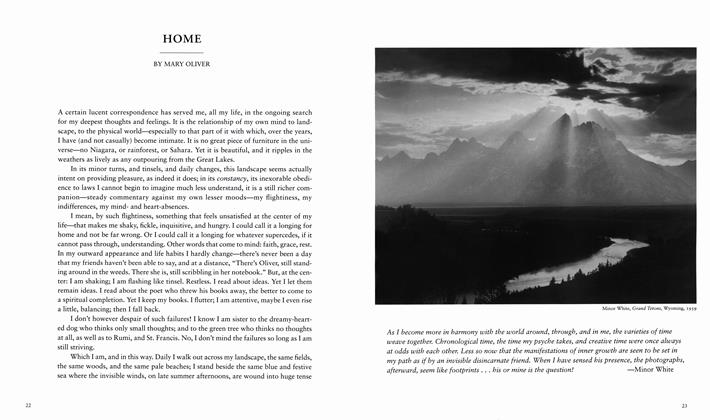

The photographers in the second division approach the landscape as a transcendental medium—one that encompasses romantic as well as spiritual experiences. Nature/landscape to photographers like Ansel Adams, Minor White, and Paul Caponigro exemplifies purity of form, and a requiem for peace and tranquility. To poet and essayist Mary Oliver it is a personal landscape, with its familiar and consistent terrain that sustains a spiritual and emotional equilibrium. She laments, “It is one of the perils of our so-called civilized age that we do not acknowledge enough, or cherish enough, this connection between soul and landscape—between our own best possibilities, and the view from our own windows.”

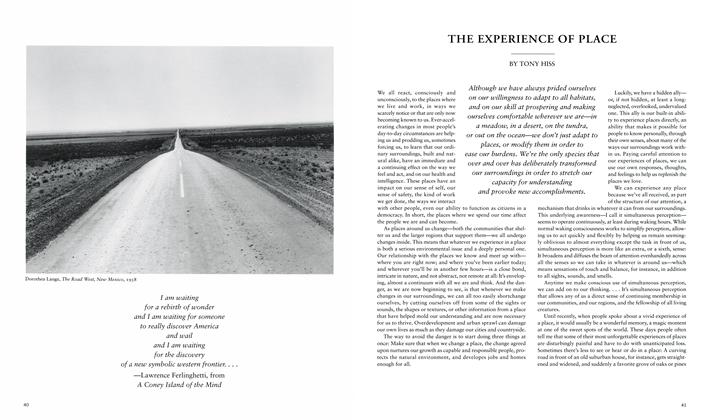

In the third section, nature/landscape is imbued with social and political significance. Man’s encounters with the landscape reflect encroachment and disregard, as both aesthetic and ecological disaster lurk in the background. This is the prevailing spirit in the work of Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Frank Gohlke, Richard Misrach, and Marilyn Bridges. Author Tony Hiss writes on “the experience of place” and its impact on our daily lives. He points out that “the danger, as we are now beginning to see, is that whenever we make changes in our surroundings, we can too easily shortchange ourselves. Over-development and urban sprawl can damage our lives as much as they damage our cities and countryside.”

The fourth section is introduced by art critic and essayist Lucy R. Lippard, who discusses the impact of a creative and spiritual climate on contemporary landscape photography, and focuses on the so-called postmodern element in its midst—photographers like Tseng Kwong Chi, who self-consciously intervene in or thrust themselves upon the land, or who alter the landscape in some manner like Jerry N. Uelsmann, Walter De Maria, and Sally Mann. Lippard observes that revisionist theory and the “less-than-god-given modern incarnations” of nature, infused with social and environmental implications, have incited new interpretations by photographers, though she notes that “the dilemma of meaning” often obscures their intentions. And yet, through the artistry of these photographers, qualities of spirit can still be experienced through their work.

Gratitude is expressed to all who have worked on this issue, especially to Dr. John Rohrbach, Associate Curator of Photographs at the Amon Carter Museum, who helped to initiate the project, and who benefited this issue with his research skills and vision.

THE EDITORS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Experience Of Place

Winter 1998 By Tony Hiss -

Postnatural

Winter 1998 By Bill Mckibben -

Home

Winter 1998 By Mary Oliver -

Outside (but Not Necessarily Beyond) The Landscape

Winter 1998 By Lucy R. Lippard -

People And Ideas

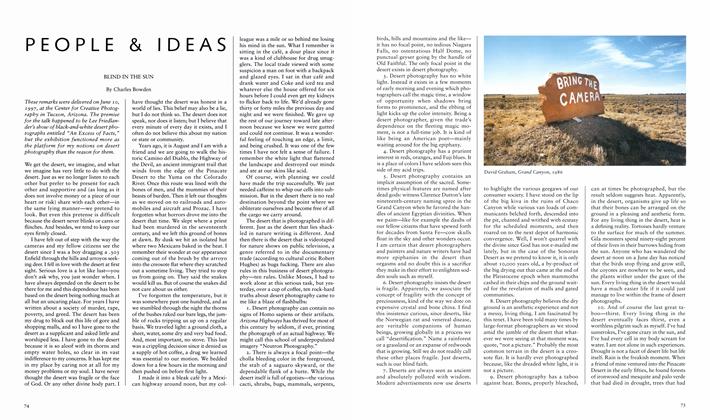

People And IdeasBlind In The Sun

Winter 1998 By Charles Bowden -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasThe Buzz About Paparazzi: Marcello Mastroianni Remembers Working With Federico Fellini And Tazio Secchiaroli, The First Paparazzo

Winter 1998 By Gloria Satta

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

The Editors

-

Editor's Note

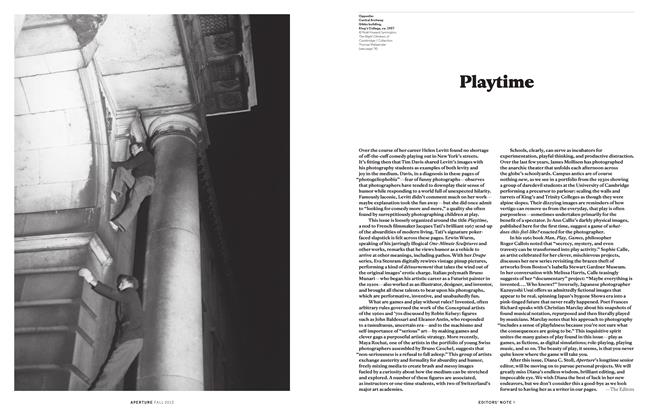

Editor's NotePlaytime

Fall 2013 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

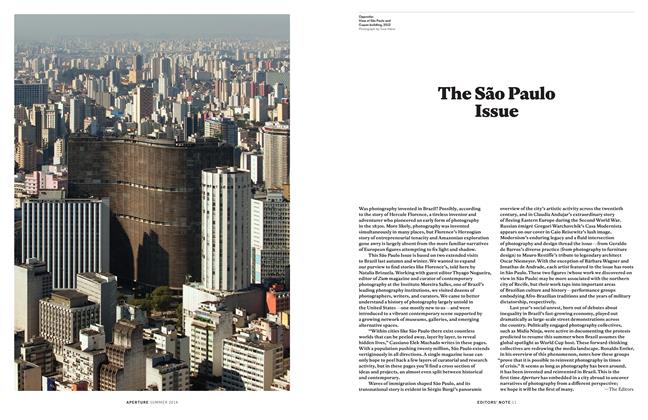

Editor's NoteThe São Paulo Issue

Summer 2014 By The Editors -

Pictures

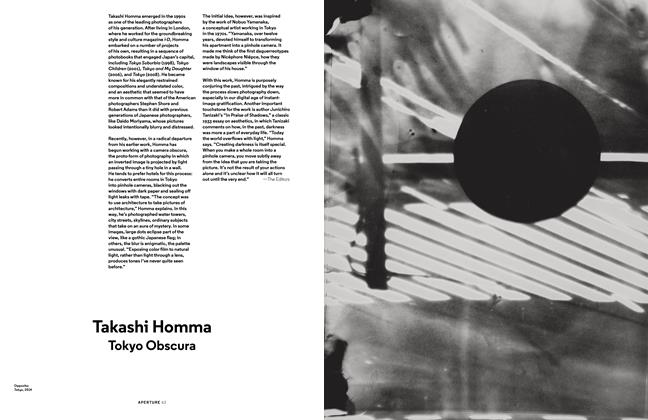

PicturesTakashi Homma

Summer 2015 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteLos Angeles

Fall 2018 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

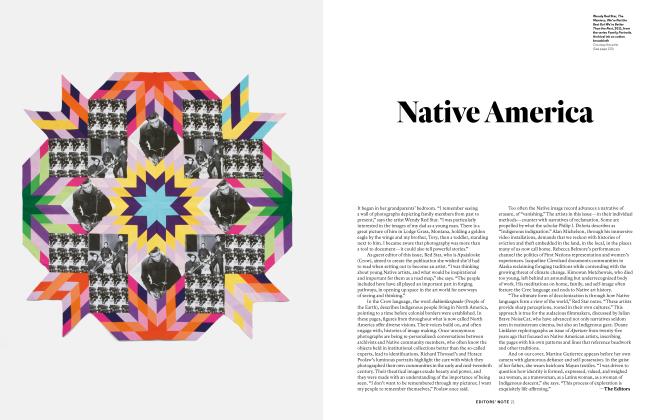

Editor's NoteNative America

Fall 2020 By The Editors -

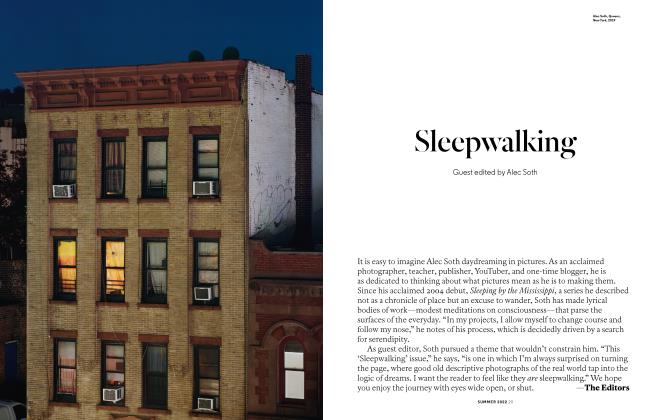

Sleepwalking

SUMMER 2022 By The Editors

Editor's Note

-

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteEditors' Note

Summer 2000 -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteAperture

Summer 1992 By Martin Munkacsi -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteBrush Fires In The Social Landscape

Fall 1994 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteSpecimens And Marvels: William Henry Fox Talbot The Invention Of Photography

Winter 2000 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteLit.

Winter 2014 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteTokyo

Summer 2015 By The Editors