BEFORE THE FLOOD: NACHO LÓPEZ AND HÉCTOR GARCÍA

The Fifties

Carlos Monsiváis

Appreciation for the artistic dimensions of photography is a recent phenomenon in Mexico: as late as the 1970s, the usual thing was to applaud the technological miracle and leave it at that, reserving all astonishment for the invention itself. And if photography was only occasionally considered art, the kind of photography destined for immediate publication—photojournalism—was seen as having only one clear merit, that of being a gift of opportunity. This delay in acknowledging an artistic discipline explains why two great photographers, Nacho López and Héctor García, were for so long considered merely visual reporters, no doubt excellent in their way but hardly creators. The quality of the reproduction of their work was not even minimally acceptable, and no public existed with an eye schooled enough to admire their talent.

Unconcerned by this lack of appreciation, López and Garcia made full use of certain qualities of the journalist’s métier: exceptional situations, the need to sum up a broad phenomenon in a single image, and the pressure of circumstances, which, in conjunction with a critical temperament, can refine one’s point of view. To all of this, both photographers added the lessons of their inevitable teacher, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, from whom they learned something indispensable in a country like Mexico: an aesthetic perspective in which attention is paid not to the prestige or status of the subject matter, but to what is disdained or barely noticed, to what can only be unlocked by the keys of poetry, be it a woman combing her hair reinvented by the light, or the halo of blood around a murdered workman.

Alvarez Bravo’s teachings ran deep with López and Garcia, but his disciples aimed for lyrical exaltation in only a part of their work. Some of their photographs can undoubtedly be called poetic, but that quality was not their habitual target. Instead they focused on another zone of the aesthetic, one that derives its energy from a great city that neither entirely abandons tradition nor fully joins with modernity. What these photographers found in the megalopolis—in the ebb and flow of the streets, the constant new environments—certainly can be poetic but is more often something only definable by photography itself: the photographic event that incorporates violence and politics and entertainment and sexual appetite and the bedazzlement of the senses. At the center of López and Garcia’s interest was the artistic expressiveness to be found in documenting city life.

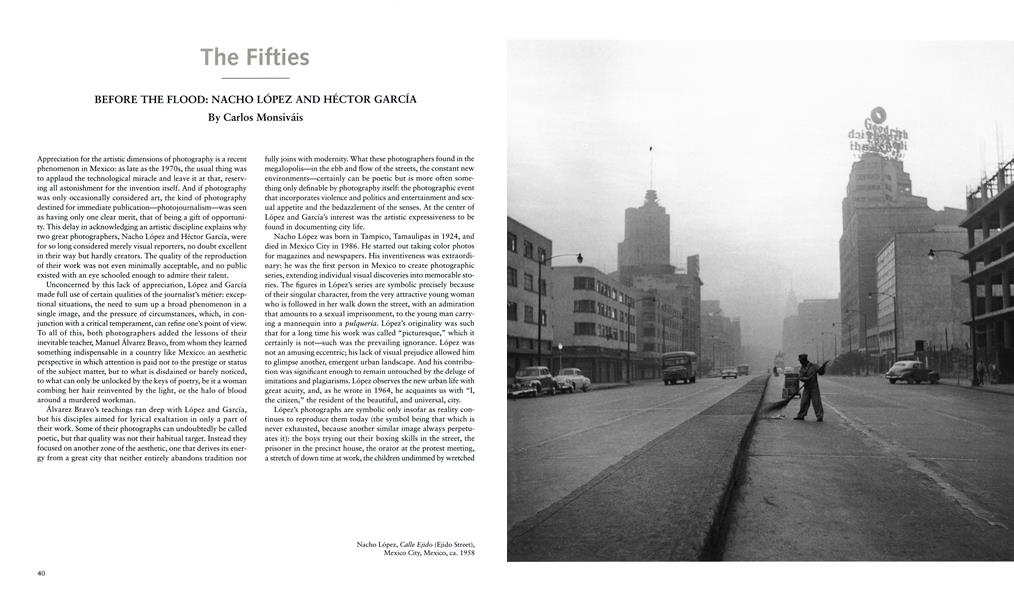

Nacho López was born in Tampico, Tamaulipas in 1924, and died in Mexico City in 1986. He started out taking color photos for magazines and newspapers. His inventiveness was extraordinary: he was the first person in Mexico to create photographic series, extending individual visual discoveries into memorable stories. The figures in López’s series are symbolic precisely because of their singular character, from the very attractive young woman who is followed in her walk down the street, with an admiration that amounts to a sexual imprisonment, to the young man carrying a mannequin into a pulquería. López’s originality was such that for a long time his work was called “picturesque,” which it certainly is not—such was the prevailing ignorance. López was not an amusing eccentric; his lack of visual prejudice allowed him to glimpse another, emergent urban landscape. And his contribution was significant enough to remain untouched by the deluge of imitations and plagiarisms. López observes the new urban life with great acuity, and, as he wrote in 1964, he acquaints us with “I, the citizen,” the resident of the beautiful, and universal, city.

López’s photographs are symbolic only insofar as reality continues to reproduce them today (the symbol being that which is never exhausted, because another similar image always perpetuates it): the boys trying out their boxing skills in the street, the prisoner in the precinct house, the orator at the protest meeting, a stretch of down time at work, the children undimmed by wretched poverty, the crowd yearning for whatever it is that will be extinguished as soon as it disperses, the vedette in the sleazebag cabaret, the women gnawed by worry. Occasionally a photograph appears that defies all explanations and foreseeable contexts: the hands of a prisoner sticking out from beneath a cell door, a magnificent sunset over a city with a monstrous mixture of periods and styles. The image generally derives not from a quest for poetic moments but from the repertory of chance.

López handles the countryside equally well, documenting indigenous customs, proud and laughing faces, dramatic moments, rituals, and a poetry in one place unexpected, in another always a presence. His pictures of the city, though, may be his greatest contribution. Here his obsessions are dispersed across the statements and restatements of the great city—the faith that gazes unsparingly at modernity, chaos, merriment, protest, sex, solitude, drunkenness. His images say, “The nights, violent or serene, soaked with blood, alcohol, and marijuana, repeat their stories: the will to die and the same eternal passion, deceit, and crime.” In Nacho Lopez’s work the great city is an unfulfilled prophecy, an unexpected revelation, as close to festive delirium as to nightmare.

Héctor García was born in Mexico City in 1926. Like López, he began as a photo journalist, and refined his practice in that occupation; unlike López, he plunged wholeheartedly into journalism, which made it possible for him to travel and to bear witness to a wide variety of scenes and privileged moments, and ensured that a range of reactions to extreme events was always available to him. If Garcia’s work recalls anything in this respect, it is the work of the U.S. photographer Weegee, a devotee of crime scenes and the flow of urban contrasts. Garcia focuses on what the city and his work as a journalist demand of him, lying in wait not for the poetic moment but for the unexpected—or expected—image that a highly trained eye can capture instantaneously.

The artist David Alfaro Siqueiros, jailed as a “subversive,” appears in Garcia’s work, accepting the photographer’s request to pose as a figure in one of his own huge paintings. Here we also find the painter Diego Rivera in his studio, his smile rivaling the smile of an enormous cardboard doll; a lady at a gala dinner, bending down to straighten her dress; some isolated rifles lying in the Plaza de las Tres Culturas on October 2, 1968, the day of a student massacre; a cat in New York, with a lonely-looking house in the background; a woman at a reception who bows as a diplomat studies her neckline. Garcia also photographs endless street scenes, ceremonies of all kinds, writers, crowds both angry and festive, artists, urban anecdotes. The catalog is vast.

Garcia’s work as a journalist also sends him into the countryside; his series on the Huichol Indians, with their hallucinatory rituals and wanderings, is magnificent, as is his series on Oaxaca. But the fundamental element in this work is the tendency of a forced modernization to bring on poverty and overcrowding—not a timeless poverty, either, but a specifically contemporary one in its greed and shamelessness. Yet Garcia’s heroes and antiheroes have an ease and vitality. His knowing combination of tradition and unforeseen incident makes the photographs memorable; Garcia brings to his intrusions into people’s lives, his strolls through the city, an honest desire to surprise himself. An example: on a street in a poor neighborhood, a boy, in a niche for a missing saint, makes an obscene gesture at the photographer and whoever else is around. The opposite can also take place: an indigenous girl covers herself with her rebozo, leaving nothing but a single eye free to interrogate the outer world.

In the street, his native territory, Héctor García works with imagination and rigor. The asphalt jungle belongs to him, and he penetrates its enigmas without trying to impress or shock. What matters to him is grace, cynicism, vigor, the tenderness of daily life, which social disdain renders invisible but which art recovers, with feeling and irony.

Esther Allen

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

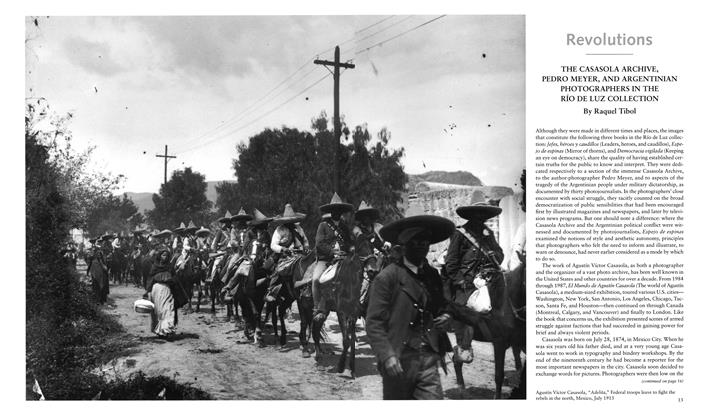

Revolutions

RevolutionsThe Casasola Archive, Pedro Meyer, And Argentinian Photographers In The Río De Luz Collection

Fall 1998 By Raquel Tibol -

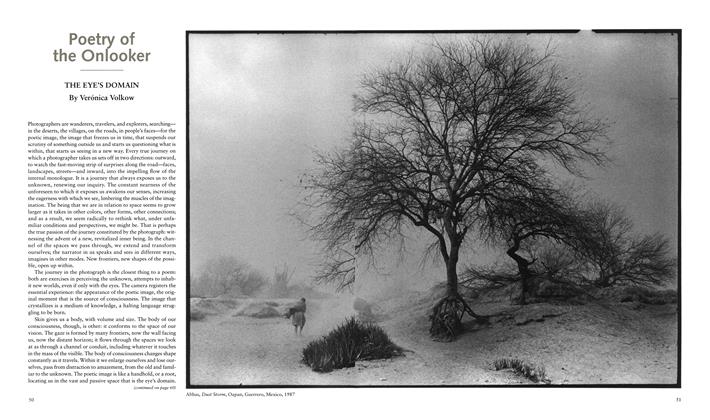

Poetry Of The Onlooker

Poetry Of The OnlookerThe Eye's Domain

Fall 1998 By Verónica Volkow -

Sweet Bitter Sweat

Sweet Bitter SweatMiguel Rio Branco

Fall 1998 By Roberto Tejada -

The American Way Of Life And Cuba

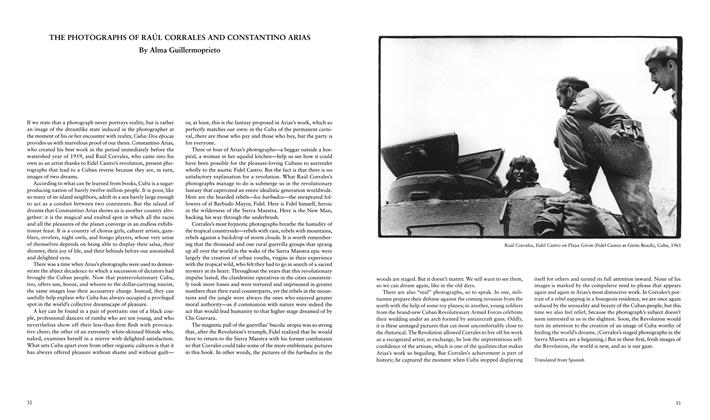

The American Way Of Life And CubaThe Photographs Of Raúl Corrales And Constantino Arias

Fall 1998 By Alma Guillermoprieto -

Río De Luz

Río De LuzThe Origins Of Río De Luz

Fall 1998 By Víctor Flores Olea -

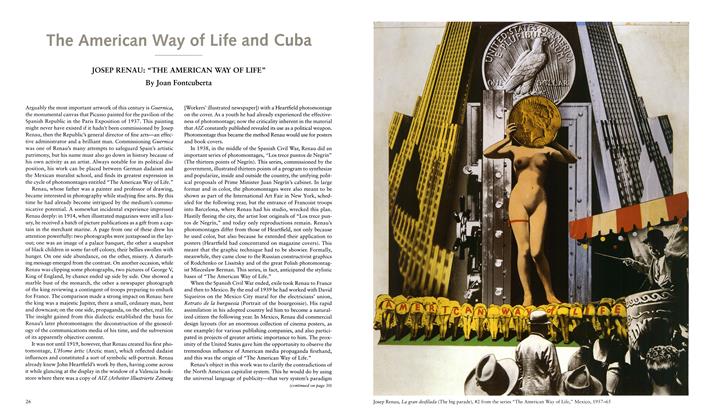

The American Way Of Life And Cuba

The American Way Of Life And CubaJosep Renau: "The American Way Of Life"

Fall 1998 By Joan Fontcuberta