The American Way Of Life And Cuba

Josep Renau: "The American Way Of Life"

Fall 1998 Joan FontcubertaJOSEP RENAU: "THE AMERICAN WAY OF LIFE"

The American Way of Life and Cuba

Joan Fontcuberta

Arguably the most important artwork of this century is Guernica, the monumental canvas that Picasso painted for the pavilion of the Spanish Republic in the Paris Exposition of 1937. This painting might never have existed if it hadn't been commissioned by Josep Renau, then the Republic's general director of fine arts—an effective administrator and a brilliant man. Commissioning Guernica was one of Renau’s many attempts to safeguard Spain’s artistic patrimony, but his name must also go down in history because of his own activity as an artist. Always notable for its political disposition, his work can be placed between German dadaism and the Mexican muralist school, and finds its greatest expression in the cycle of photomontages entitled "The American Way of Life."

Renau, whose father was a painter and professor of drawing, became interested in photography while studying fine arts. By this time he had already become intrigued by the medium’s communicative potential. A somewhat incidental experience impressed Renau deeply: in 1914, when illustrated magazines were still a luxury, he received a batch of picture publications as a gift from a captain in the merchant marine. A page from one of these drew his attention powerfully: two photographs were juxtaposed in the layout; one was an image of a palace banquet, the other a snapshot of black children in some far-off colony, their bellies swollen with hunger. On one side abundance, on the other, misery. A disturbing message emerged from the contrast. On another occasion, while Renau was clipping some photographs, two pictures of George V, King of England, by chance ended up side by side. One showed a marble bust of the monarch, the other a newspaper photograph of the king reviewing a contingent of troops preparing to embark for France. The comparison made a strong impact on Renau: here the king was a majestic Jupiter, there a small, ordinary man, bent and downcast; on the one side, propaganda, on the other, real life. The insight gained from this dialectic established the basis for Renau’s later photomontages: the deconstruction of the gnoseology of the communications media of his time, and the subversion of its apparently objective content.

It was not until 1919, however, that Renau created his first photomontage, L’Home àrtic (Arctic man), which reflected dadaist influences and constituted a sort of symbolic self-portrait. Renau already knew John Heartfield’s work by then, having come across it while glancing at the display in the window of a Valencia bookstore where there was a copy of AIZ (Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung [Workers’ illustrated newspaper] ) with a Heartfield photomontage on the cover. As a youth he had already experienced the effectiveness of photomontage; now the criticality inherent in the material that AIZ constantly published revealed its use as a political weapon. Photomontage thus became the method Renau would use for posters and book covers.

In 1938, in the middle of the Spanish Civil War, Renau did an important series of photomontages, "Los trece puntos de Negrín" (The thirteen points of Negrín). This series, commissioned by the government, illustrated thirteen points of a program to synthesize and popularize, inside and outside the country, the unifying political proposals of Prime Minister Juan Negrin’s cabinet. In large format and in color, the photomontages were also meant to be shown as part of the International Art Fair in New York, scheduled for the following year, but the entrance of Francoist troops into Barcelona, where Renau had his studio, wrecked this plan. Hastily fleeing the city, the artist lost originals of "Los trece puntos de Negrín,” and today only reproductions remain. Renau’s photomontages differ from those of Heartfield, not only because he used color, but also because he extended their application to posters (Heartfield had concentrated on magazine covers). This meant that the graphic technique had to be showier. Formally, meanwhile, they came close to the Russian constructivist graphics of Rodchenko or Lissitsky and of the great Polish photomontagist Mieceslaw Berman. This series, in fact, anticipated the stylistic bases of “The American Way of Life."

When the Spanish Civil War ended, exile took Renau to France and then to Mexico. By the end of 1939 he had worked with David Siqueiros on the Mexico City mural for the electricians’ union, Retrato de la burguesía (Portrait of the bourgeoisie). His rapid assimilation in his adopted country led him to become a naturalized citizen the following year. In Mexico, Renau did commercial design layouts (for an enormous collection of cinema posters, as one example) for various publishing companies, and also participated in projects of greater artistic importance to him. The proximity of the United States gave him the opportunity to observe the tremendous influence of American media propaganda firsthand, and this was the origin of "The American Way of Life."

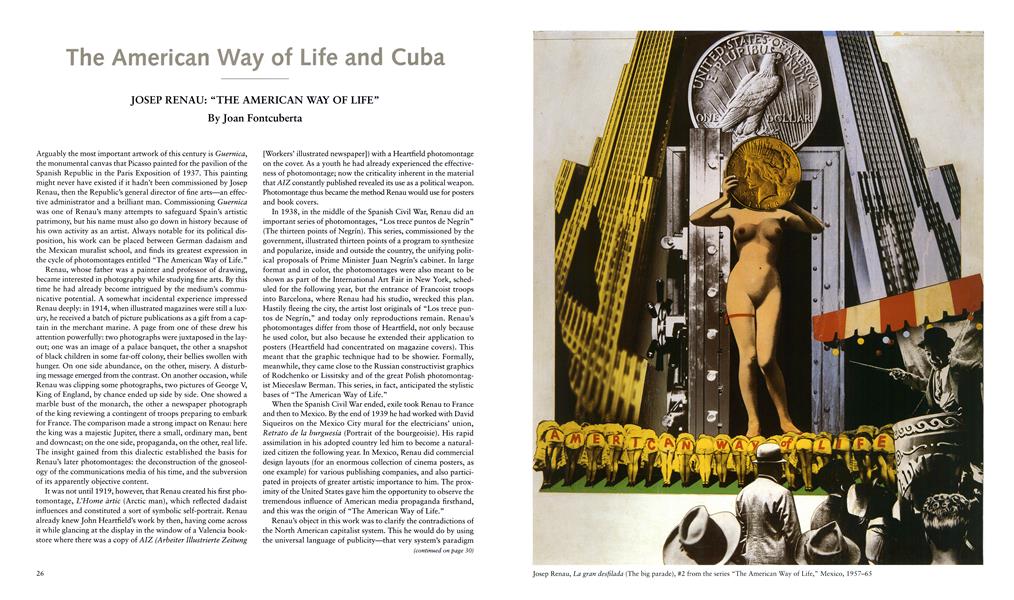

Renau’s object in this work was to clarify the contradictions of the North American capitalist system. This he would do by using the universal language of publicity—that very system’s paradigm and product. A language invented with consumerist and alienating ends in mind was thus critically subverted. Renau’s sources for the work were images that had appeared in Life, Fortune, and the New York Times, mouthpieces a priori of the slogans of peace, justice, well-being, and freedom that decorated the programs of their bosses. But Renau wanted to unveil the double face of these hypocritical and self-satisfied images, and to uncover the cost of their deceit: the repression, racism, corruption, speculation, militarization, and increasing arms production of a savage imperialism. The compositions often include quotes from the speeches of political leaders and public figures, or publicity slogans flagrantly contradicting the evidence shown in the pictures: the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima, the execution of Harold and Ethel Rosenberg, Ku Klux Klan lynchings, the commercial utilization of sex. Marilyn Monroe’s dazzling smile was set next to images of deprived minorities, a hot dog next to an electric chair. Death in Renau’s vision is the flip side of capitalist benefit.

(continued on page 30)

“The American Way of Life” cycle anticipates some of the proposals of pop art: a realism that takes mass culture as its visual model, a tendency toward flashy iconography, an irony about consumerist myths, and a great visual clarity. The work can also be linked to creative photography of the time: it is interesting, for example, to see how these photomontages agree in some ways with the disillusioned and cynical vision of Robert Frank. But Frank’s refined and sophisticated innovations in The Americans were not understood outside a limited elite of connoisseurs, while Renau took a much more belligerent and populist position. None of his photomontages is signed, and many have circulated anonymously, often outside his control. His goal was to plant in the minds of spectators, of whatever social rank and whatever cultural level, a direct and overwhelming message.

The mechanism by which the photomontages gain their significance can be studied on different levels. Where Heartfield’s work, for instance, is based on juxtaposing elements that are contradictory or absurd, Renau’s compositions are more dense and baroque, and, to catalyze spectators’ reactions, often use metaphors that are as clearly understandable as they are grotesque. This grotesquerie—in contrast to Heartfield’s gravity—Renau may have learned from the folklore of Valencia, its greatest manifestation being the fallas, huge bonfires set on St. John’s Eve to consume ninots, papier-mâché dolls satirizing public personages or vices. The burlesque tone of these representations proves the abundance of stereotypes forged by popular creativity.

Renau sacrificed formal considerations to meaning, natural color to dramatic effect. The forced linkages and strident palette of the works were intended to heighten their impact. Concentrating on his message, the artist paid little attention to technical execution: he made no effort, for example, to hide the seams between the different graphic elements. Renau believed that the mere act of placing different images on the same plate forced the spectator to make connections between them. In contrast to many other photomontagists, he worked exclusively from found graphic materials, despite his own skill with a camera. Heartfield and Renau, who respected each other’s ideological beliefs, kept up an interesting polemic regarding the plastic treatment of their respective styles. Renau, for example, argued that the chromatic austerity embraced by Heartfield was an antibourgeois necessity during the Weimar Republic, but that in an era dominated by the mass media and publicity, one had to fight the establishment with the new visual rhetoric imposed by the establishment itself.

In 1958, Renau went to the former East Germany, and in conceptual terms the corpus of “The American Way of Life” was finished. In Berlin, however, he continued to elaborate on the ideas he had worked out, until completing the more than 200 originals that made up the cycle. A selection of these photomontages was published for the first time in Berlin in 1967, under the title Fata Morgana USA. Today this assemblage of images remains the classical and definitive reference work of an art that, rather than just helping us to see the world, helps us to think of it critically in order to understand it and transform it.

Cola Franzen

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Revolutions

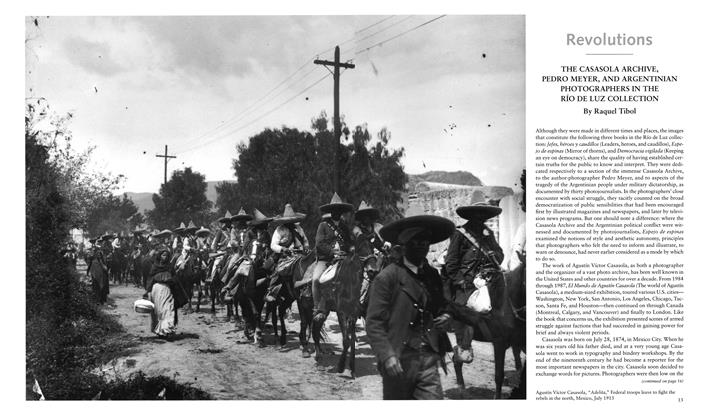

RevolutionsThe Casasola Archive, Pedro Meyer, And Argentinian Photographers In The Río De Luz Collection

Fall 1998 By Raquel Tibol -

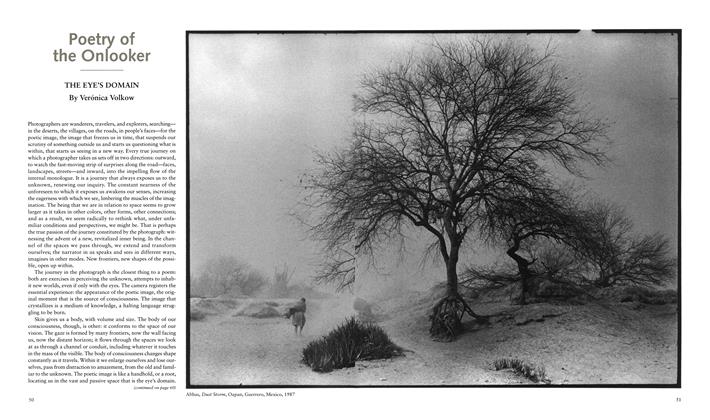

Poetry Of The Onlooker

Poetry Of The OnlookerThe Eye's Domain

Fall 1998 By Verónica Volkow -

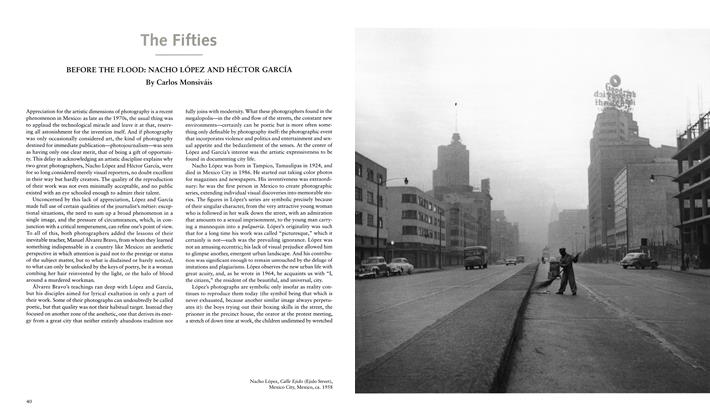

The Fifties

The FiftiesBefore The Flood: Nacho López And Héctor García

Fall 1998 By Carlos Monsiváis -

Sweet Bitter Sweat

Sweet Bitter SweatMiguel Rio Branco

Fall 1998 By Roberto Tejada -

The American Way Of Life And Cuba

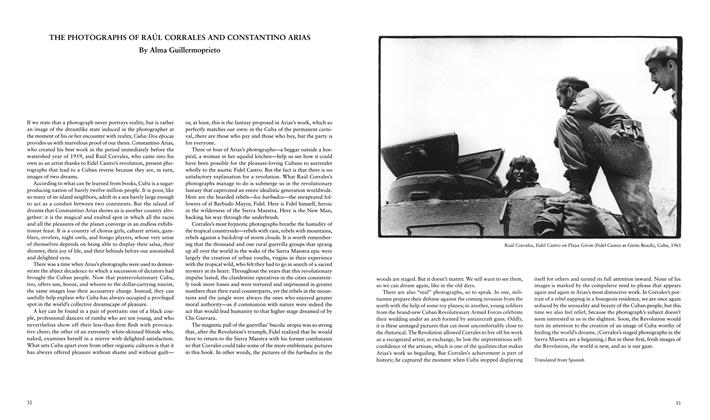

The American Way Of Life And CubaThe Photographs Of Raúl Corrales And Constantino Arias

Fall 1998 By Alma Guillermoprieto -

Río De Luz

Río De LuzThe Origins Of Río De Luz

Fall 1998 By Víctor Flores Olea