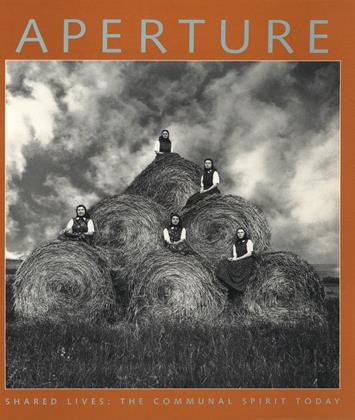

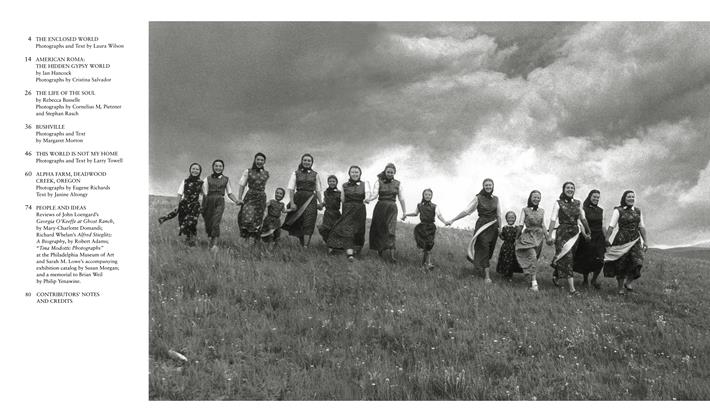

THIS WORLD IS NOT MY HOME

LARRY TOWELL

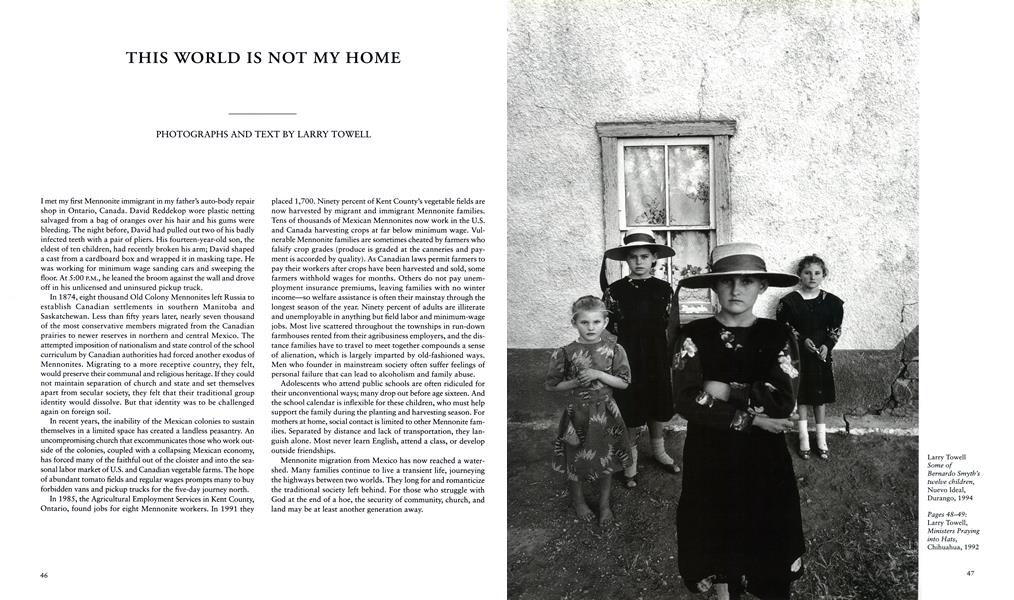

I met my first Mennonite immigrant in my father's auto-body repair shop in Ontario, Canada. David Reddekop wore plastic netting salvaged from a bag of oranges over his hair and his gums were bleeding. The night before, David had pulled out two of his badly infected teeth with a pair of pliers. His fourteen-year-old son, the eldest of ten children, had recently broken his arm; David shaped a cast from a cardboard box and wrapped it in masking tape. He was working for minimum wage sanding cars and sweeping the floor. At 5:00 P.M., he leaned the broom against the wall and drove off in his unlicensed and uninsured pickup truck.

In 1874, eight thousand Old Colony Mennonites left Russia to establish Canadian settlements in southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Less than fifty years later, nearly seven thousand of the most conservative members migrated from the Canadian prairies to newer reserves in northern and central Mexico. The attempted imposition of nationalism and state control of the school curriculum by Canadian authorities had forced another exodus of Mennonites. Migrating to a more receptive country, they felt, would preserve their communal and religious heritage. If they could not maintain separation of church and state and set themselves apart from secular society, they felt that their traditional group identity would dissolve. But that identity was to be challenged again on foreign soil.

In recent years, the inability of the Mexican colonies to sustain themselves in a limited space has created a landless peasantry. An uncompromising church that excommunicates those who work outside of the colonies, coupled with a collapsing Mexican economy, has forced many of the faithful out of the cloister and into the seasonal labor market of U.S. and Canadian vegetable farms. The hope of abundant tomato fields and regular wages prompts many to buy forbidden vans and pickup trucks for the five-day journey north.

In 1985, the Agricultural Employment Services in Kent County, Ontario, found jobs for eight Mennonite workers. In 1991 they placed 1,700. Ninety percent of Kent County’s vegetable fields are now harvested by migrant and immigrant Mennonite families. Tens of thousands of Mexican Mennonites now work in the U.S. and Canada harvesting crops at far below minimum wage. Vulnerable Mennonite families are sometimes cheated by farmers who falsify crop grades (produce is graded at the canneries and payment is accorded by quality). As Canadian laws permit farmers to pay their workers after crops have been harvested and sold, some farmers withhold wages for months. Others do not pay unemployment insurance premiums, leaving families with no winter income—so welfare assistance is often their mainstay through the longest season of the year. Ninety percent of adults are illiterate and unemployable in anything but field labor and minimum-wage jobs. Most live scattered throughout the townships in run-down farmhouses rented from their agribusiness employers, and the distance families have to travel to meet together compounds a sense of alienation, which is largely imparted by old-fashioned ways. Men who founder in mainstream society often suffer feelings of personal failure that can lead to alcoholism and family abuse.

Adolescents who attend public schools are often ridiculed for their unconventional ways; many drop out before age sixteen. And the school calendar is inflexible for these children, who must help support the family during the planting and harvesting season. For mothers at home, social contact is limited to other Mennonite families. Separated by distance and lack of transportation, they languish alone. Most never learn English, attend a class, or develop outside friendships.

Mennonite migration from Mexico has now reached a watershed. Many families continue to live a transient life, journeying the highways between two worlds. They long for and romanticize the traditional society left behind. For those who struggle with God at the end of a hoe, the security of community, church, and land may be at least another generation away.

THE SUN SIFTS across the blood of a sow that was slaughtered this morning. Dust settles on the roofs of houses, covering them with a fine layer of sand. The sun cracks and burns, waiting for rain in a dry year. In the near darkness, dogs bark from barnyard to barnyard at the arrival of man into their yards, or just passing by.

Fathers are in the barns milking their cows with the women and children. For the third year, the men slave into the desert with their wagons at sunrise to harvest cactus for cattle fodder. For the third year in a row, a bale of hay costs more than half of a man’s daily wage. The men in the barns fill their pails, straining the milk. It has the rank odor of digested cactus. The cactus flushes through the cattle like water and its needles often catch in the cows’ stomachs and make them complain. You can hear cattle’s bawl mix with dog’s bark as children haul milk to the roadside. Cats dart like shadows among the girls pulling wagons of milk to the road. Although relieved of their milk, the cattle continue to bellow.

As I walk from the house where David Reddekop was born, the dust puffs up like talcum powder. The road is deeply rutted by wagon wheels and there is dried grass between the ruts. A wine bottle that Cornelius Klassen tossed aside this morning is coated already with a very fine layer of dust. The sun is almost gone now.

A little wagon approaches almost furtively, with Herman Wall and his wife silhouetted inside of it. They are carting a forty-fivegallon drum to a communal windmill that pumps water for those without wells of their own. Herman has large ears and protruding teeth for which he was taunted as a boy. Now the same few schoolmates have become men and they harangue him still. Herman reins in his horse and leans toward me, whispering. I’ve never seen a Mennonite beg money for food.

This is the first time.

ABRAHAM AND HELEN Dyck’s bouse is set in the solitary desert.

Its kitchen is sparse but brightly painted. From this room, their fourteen children have scattered northward to harvest vegetables and fruit. Poverty and debt sink many in Mexico.

The hot light from a Coleman lamp, which is saved for special occasions, illuminates the bible Abraham reads. The lamp gives off a liquid heat. The light is sharp and much brighter than kerosene. Although I cannot decipher German, judging from Abraham’s place within the text I guess he is somewhere in the New Testament. He has a pained look on his face and seems unconscious of my presence at the table. Maybe he is reading of the crucifixion or has accepted some chastisement in a personal way.

The lamp, clear and almost divine in its heat, spills its new-coin brightness all over the table.

Mounted in the ceiling is a six-volt vehicle bulb salvaged from a car and wired for battery operation. Abe’s head is bent low and his face has the quality of light itself. He does not use the bulb because, although it is somewhat ingenious, the church ministers have visited to remind him of its implications of worldliness. There are two voices. Satan loves his soul as much and as dearly as the Lord does.

IN CORNELIUS DYCK’S BARNYARD an early model Chevy, its wheels removed, sits with one door propped open, allowing his chickens in and out. Tin covers the windows. The hack taillight is gone. Perhaps the sedan transported a family here before its conversion. The ministers are now at ease.

For these Mennonites the internal combustion engine can exist only in the work-horse tractor. Most are two-cylinder John Deere “A”s: 1948 to 1952. All are steel-wheeled. Should a modern machine arrive on wheels of rubber, full of air and inner tubes, it must be stripped, humiliated like a prodigal child, for these are the devil’s wheels and must be replaced with iron.

This world is not my home I’m just passing through —Traditional song

IN ABE’S BARNYARD a rusted John Deere “A”. . .

Abe has sliced the tires from an old car and sewn them with wire onto the front wheels of his tractor to help reduce bumps that the steel wheels transferred along the shaft into the steering wheel and through his hands shaking his whole body on the iron frame. There are no inner tubes, just thin and treadless strips of rubber. This combination of wire, rubber, and steel has caused some confusion in his barnyard and I have even noticed the chickens picking at the rubber when they pass by. The ministers Larr>' Towell> Some °f,he °V°h" Martens, La Batea, Zacatecas, 1994 have been unable to agree, and therefore do not pass judgment. They have left it to Mr. Abraham Dyck, father of fourteen, to wrestle with his angel at the kitchen table in the purest and hottest of light.

In the morning, he does not drive the tractor onto the road where it can be seen, but through the wire gate that was held closed all night by its binder-twine loop, straight into the bean field that is dry and forever thirsty

he drives his rubber over the blood of the sow.

IN THE DISTANCE, HERMAN WALL crawls like an insect into the desert, his buggy full of water, cactus, light, and half a pig.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

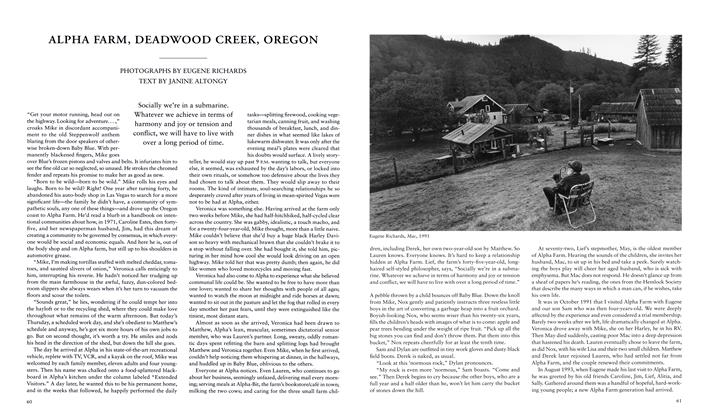

Alpha Farm, Deadwood Creek, Oregon

Summer 1996 By Janine Altongy -

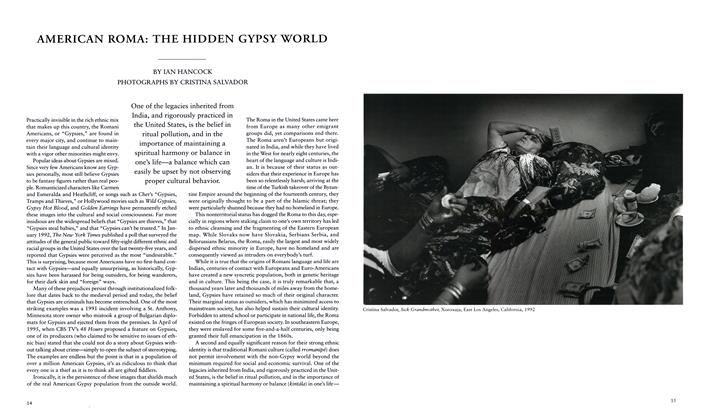

American Roma: The Hidden Gypsy World

Summer 1996 By Ian Hancock -

The Enclosed World

Summer 1996 By Laura Wilson -

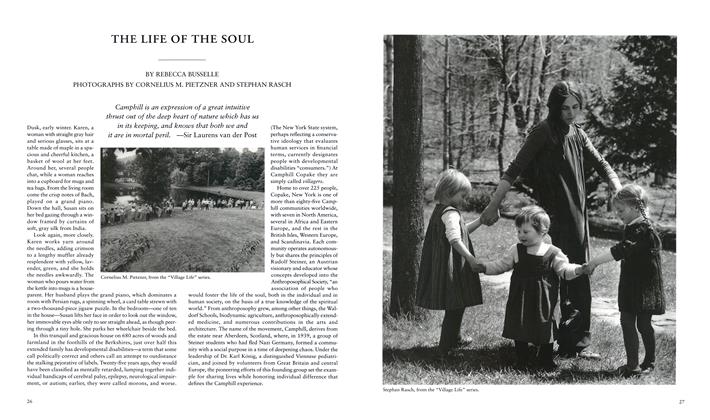

The Life Of The Soul

Summer 1996 By Rebecca Busselle -

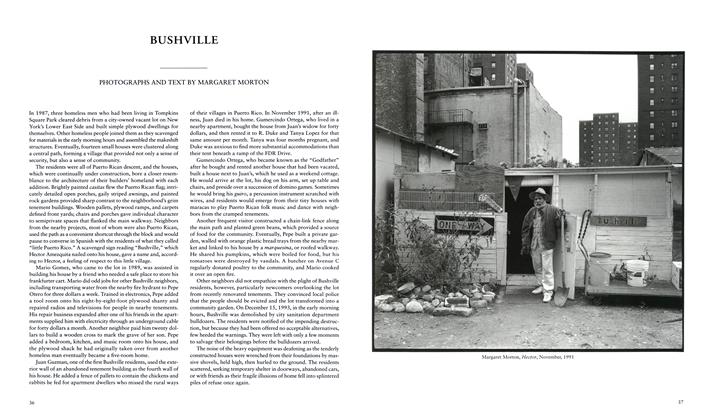

Bushville

Summer 1996 By Margaret Morton -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAlfred Stieglitz: A Biography, Richard Whelan

Summer 1996 By Robert Adams