BUSHVILLE

MARGARET MORTON

In 1987, three homeless men who had been living in Tompkins Square Park cleared debris from a city-owned vacant lot on New York's Lower East Side and built simple plywood dwellings for themselves. Other homeless people joined them as they scavenged for materials in the early morning hours and assembled the makeshift structures. Eventually, fourteen small houses were clustered along a central path, forming a village that provided not only a sense of security, but also a sense of community.

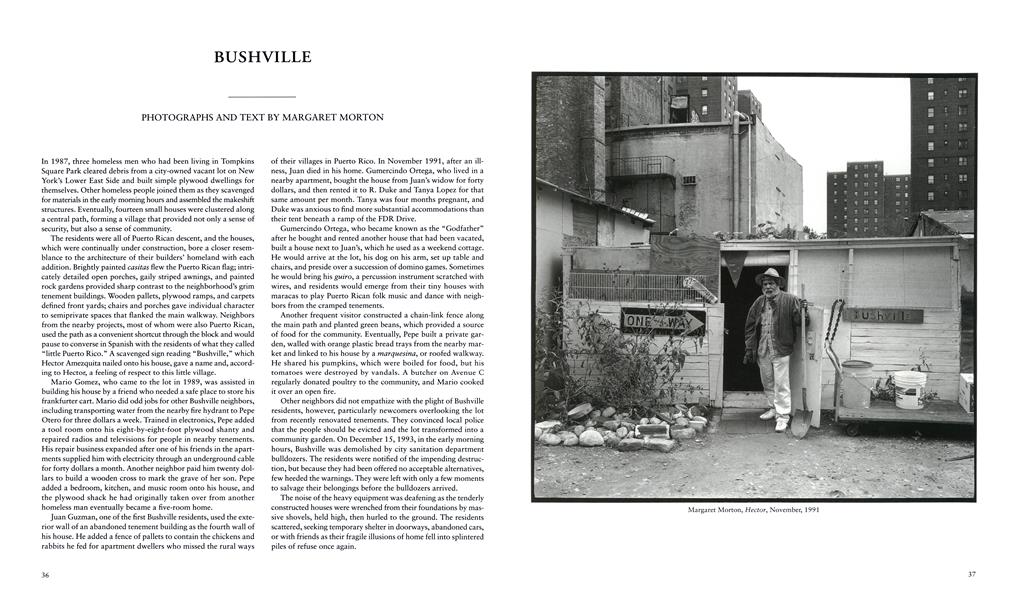

The residents were all of Puerto Rican descent, and the houses, which were continually under construction, bore a closer resemblance to the architecture of their builders’ homeland with each addition. Brightly painted casitas flew the Puerto Rican flag; intricately detailed open porches, gaily striped awnings, and painted rock gardens provided sharp contrast to the neighborhood’s grim tenement buildings. Wooden pallets, plywood ramps, and carpets defined front yards; chairs and porches gave individual character to semiprivate spaces that flanked the main walkway. Neighbors from the nearby projects, most of whom were also Puerto Rican, used the path as a convenient shortcut through the block and would pause to converse in Spanish with the residents of what they called “little Puerto Rico.” A scavenged sign reading “Bushville,” which Hector Amezquita nailed onto his house, gave a name and, according to Hector, a feeling of respect to this little village.

Mario Gomez, who came to the lot in 1989, was assisted in building his house by a friend who needed a safe place to store his frankfurter cart. Mario did odd jobs for other Bushville neighbors, including transporting water from the nearby fire hydrant to Pepe Otero for three dollars a week. Trained in electronics, Pepe added a tool room onto his eight-by-eight-foot plywood shanty and repaired radios and televisions for people in nearby tenements. His repair business expanded after one of his friends in the apartments supplied him with electricity through an underground cable for forty dollars a month. Another neighbor paid him twenty dollars to build a wooden cross to mark the grave of her son. Pepe added a bedroom, kitchen, and music room onto his house, and the plywood shack he had originally taken over from another homeless man eventually became a five-room home.

Juan Guzman, one of the first Bushville residents, used the exterior wall of an abandoned tenement building as the fourth wall of his house. He added a fence of pallets to contain the chickens and rabbits he fed for apartment dwellers who missed the rural ways of their villages in Puerto Rico. In November 1991, after an illness, Juan died in his home. Gumercindo Ortega, who lived in a nearby apartment, bought the house from Juan’s widow for forty dollars, and then rented it to R. Duke and Tanya Lopez for that same amount per month. Tanya was four months pregnant, and Duke was anxious to find more substantial accommodations than their tent beneath a ramp of the FDR Drive.

Gumercindo Ortega, who became known as the “Godfather” after he bought and rented another house that had been vacated, built a house next to Juan’s, which he used as a weekend cottage. He would arrive at the lot, his dog on his arm, set up table and chairs, and preside over a succession of domino games. Sometimes he would bring his güiro, a percussion instrument scratched with wires, and residents would emerge from their tiny houses with maracas to play Puerto Rican folk music and dance with neighbors from the cramped tenements.

Another frequent visitor constructed a chain-link fence along the main path and planted green beans, which provided a source of food for the community. Eventually, Pepe built a private garden, walled with orange plastic bread trays from the nearby market and linked to his house by a marquesina, or roofed walkway. He shared his pumpkins, which were boiled for food, but his tomatoes were destroyed by vandals. A butcher on Avenue C regularly donated poultry to the community, and Mario cooked it over an open fire.

Other neighbors did not empathize with the plight of Bushville residents, however, particularly newcomers overlooking the lot from recently renovated tenements. They convinced local police that the people should be evicted and the lot transformed into a community garden. On December 15, 1993, in the early morning hours, Bushville was demolished by city sanitation department bulldozers. The residents were notified of the impending destruction, but because they had been offered no acceptable alternatives, few heeded the warnings. They were left with only a few moments to salvage their belongings before the bulldozers arrived.

The noise of the heavy equipment was deafening as the tenderly constructed houses were wrenched from their foundations by massive shovels, held high, then hurled to the ground. The residents scattered, seeking temporary shelter in doorways, abandoned cars, or with friends as their fragile illusions of home fell into splintered piles of refuse once again.

HECTOR Before me, this place was garbage, you know. There was nothing here. I built this house myself. I started it. I carry all these things myself over here, from the street, from everywhere, found them on Eighth Avenue, First Avenue, every piece of wood,

I found it. Little by little, little by everything. I carried it all—for more than two years. • The first time that I move over here, I start like a poor person. Now I feel better, now I feel comfortable. Nobody bother me. I have to do it, because Tm an old man already.

Tm on to fifty-five, too much for me, for me it’s like a hundred. • This is my work. I can’t work here, I can’t work there. This is something I’ve got to do with my life. I figure if I don’t do something here, my mind will die. I am my own boss and I know what I have to do, what I need, what I don’t need. I don’t call nobody to help me.

DUKE I grew up in the southern part of the United States; North Carolina. I like this because it’s not like a New York atmosphere. It’s like a little village inside of New York. The people here are Puerto Rican and come from that rural country life. They like this feeling. If they move into this city housing, it won’t feel like this. • When we first moved in here a guy had died in here, you knew the guy. He stayed in here three days. Well, we seen this guy in here a couple times—his spirit. Tanya has. I have. After that we never blew the candles out at night. Tanya won’t spend the night here alone. That’s why the place is haunted. Because his spirit is restless. • I saw smoke coming out around the fringe of the door.

And I can’t let Mario’s house burn up while he’s gone. I smashed the door open and I’m trying to tear this board off the wall to get the fire out and as I’m putting the fire out I look and I see a hand laying off the bed and it was Mario’s girl. I said, “Get out. It’s on fire!” They jumped right up. Mario was in shock. Everytime she sees me she says, “Thanks Duke. If it wasn’t for you, we would have probably died in there. ”

Neighbors from the nearby projects, most of whom were also Puerto Rican, used the path as a convenient shortcut through the block and would pause to converse in Spanish with the residents of what they

called "little Puerto Rico." A scavenged sign reading "Bushville," which Hector Amezquita nailed onto his house, gave a name and, according to Hector, a feeling of respect to this little village.

PEPE Otero means “watchman. ” That’s what I am. I watch out for everybody here. • I’m no architect, God is the architect, he is the best, the best architect in town. This, when I took over, was nothing, nothing. I had so many leaks, leaking all over, and too low, I had to push it up two inches more. • I came to this country because somebody told me, “Oohh, you could make a lot of money in typesetting.” I said, “Oh yeah? Then I’ll go to New York. ” When I came to New York, I got a big, bad surprise, because in those times, the minimum salary was thirty-four dollars a week. I was making more money in Puerto Rico. • The kitchen is still unfinished, have to finish the kitchen. Then I going to start the bathroom, soon as the weather get a little warmer—if I still alive.

DUKE The guy said, “Well, I’ll rent it to you real cheap, you’ll just have to work on it yourself, ” so I cleaned it out, worked on the roof, put the window in, and now I’m working on some heat. I was thinking about building a little fireplace. • I’ve been living here almost three years myself, and Pepe, he’s been living here longer than that. And there’s other people been living here longer than that, and it’s sort of like a home. We don’t have money to move up into these buildings. We don’t have money to move anyplace. We’ve been staying here for three years, and it’s like a home to us.

HECTOR I figure this is my breakthrough to stay here, because I believe in God. But sooner or later—the city— they going to chop these houses down. I want to know, will they put something here for the people working hard? They suffer making the houses here. I would like to know if they are going to take care of those like me. Everywhere we go they wind up

TANYA running us out and I have to start all over again. Duke always carried that little house he made from plastic. He carry that all the way from Sixth to Tenth Street, from Tenth Street to East River Park. That way I can sleep well.

DUKE I don’t know why they want to tear it down. I mean the place has a sort of a feel to it, because children come through here everyday. There’s never ever been a problem with any kids getting hurt or anything. Kids come here, they run through here. Every afternoon they play out here.

There’s never ever been a problem. • There aren’t any more little homeless villages anywhere in New York City. This is the last one. I have my little home here. Now I find myself in the mornings about five or six o’clock listening for these trucks, because they said they’re gonna bring bulldozers and dumpsters and backend and front-end lifters, and they’re gonna clear this place away. And I find myself listening for some bulldozer to come creeping off some truck. It’s like some monster and I know I have to get out of the way. It’s gonna eat me up and I’ll move on. But I’ve adapted myself to all the places and things I’ve done, and I feel like after I got through the war in Vietnam, I can deal with all this stuff. Even though it bothers you, when they come with the bulldozers and all that, I’ll walk down the street and I’ll look back and say, okay, have it. I’m just going on to the next stage. You have to do that or you gonna go crazy with the bureaucracy stepping on you and people not caring about you. Hey, I built a pretty thick wall and you know, it’s not gonna bother me. • Tanya was just saying last night, “They can’t come without warning us, can they?” Yeah, I said, but we’ve been through that before. I try to get her ready, like hey don’t worry about it. I’ve always had a place for her. I’ve made them all have a sort of home feeling, but this one had more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

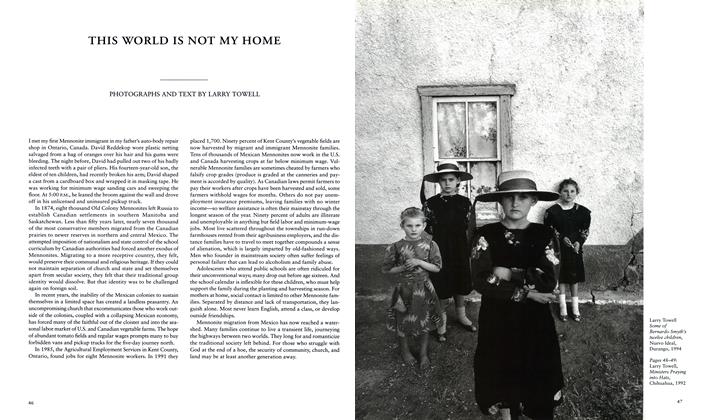

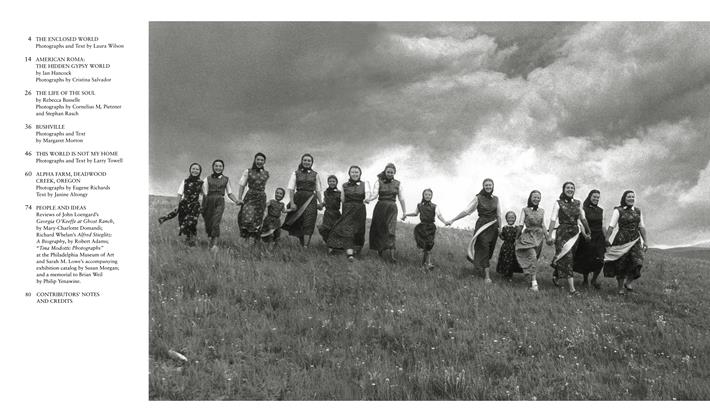

This World Is Not My Home

Summer 1996 By Larry Towell -

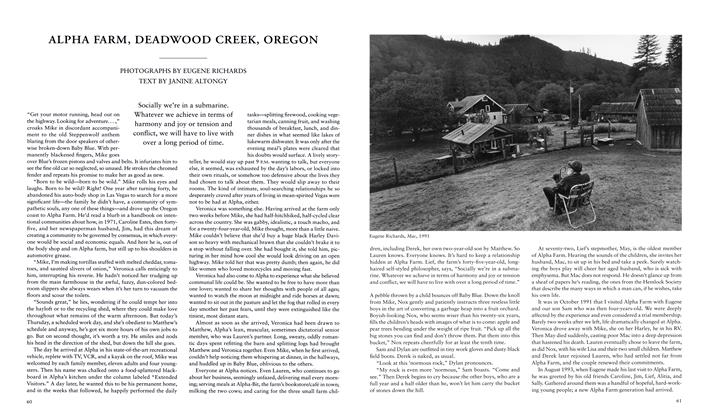

Alpha Farm, Deadwood Creek, Oregon

Summer 1996 By Janine Altongy -

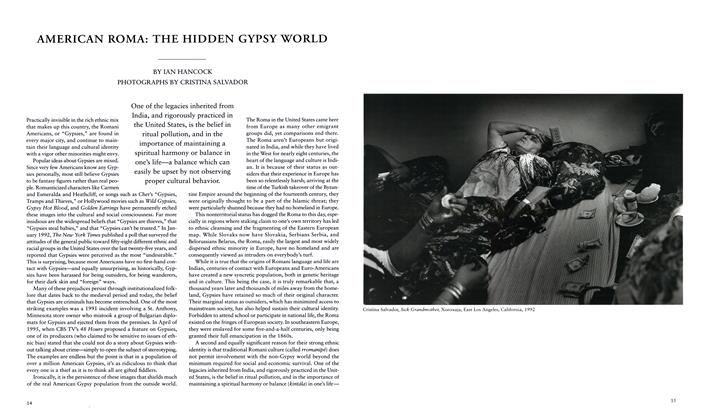

American Roma: The Hidden Gypsy World

Summer 1996 By Ian Hancock -

The Enclosed World

Summer 1996 By Laura Wilson -

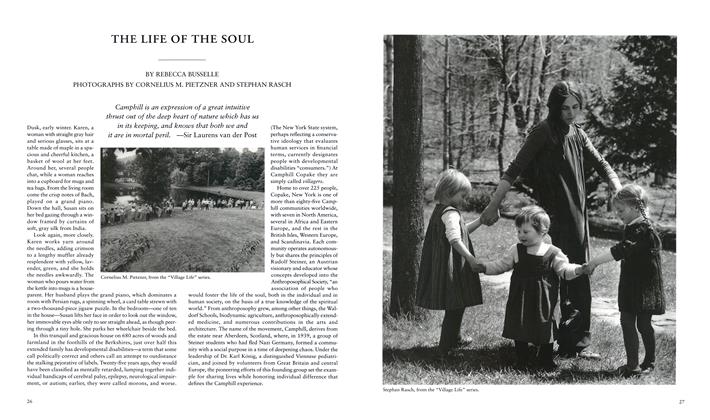

The Life Of The Soul

Summer 1996 By Rebecca Busselle -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasAlfred Stieglitz: A Biography, Richard Whelan

Summer 1996 By Robert Adams