SANTERÍA: AN ALTERNATIVE PULSE

ELIZABETH HANLY

The drumming never stops in Cuba—congas mostly, skin on skin beating out eerie rhythms soft as Cuba itself. Drumming can be heard from jails and from cemeteries and on some nights even from the middle of the woods as old men teach their great-grandchildren as they were taught, at the roots of what Afro-Cubans have always regarded as the sacred ceiba tree. Similar drumming underpins the parade of showgirls, dressed often as chandeliers, in Cuba’s grand old cabaret, the Tropicana, where the songs are all about sex and longing and growing old. During worker-day celebrations, that drumming undercuts the militancy of revolutionary anthems: something languid is added to the mix. Drumming in Cuba seems always to touch on desire. And every bit of the drumming, like the island’s soul itself, is seeped in the sacred rhythms of Santería.

Today Cuba is desperate, with its economy in free fall and many people hungry. And still the island remains feisty. “Cuba must be made of cork,” one joke goes, “otherwise the island would have sunk long ago.” Its religion deserves at least some of the credit.

The Catholic Church never had the hold in Cuba that it did in most other Latin countries. Perhaps the influence of Africa was just too strong. (As a sugar producer, Cuba was a major center for slave traffic in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.) Perhaps an island “born out of whoring, smuggling, and drinking,” as Cuban art critic Gerardo Mosquera put it, needed a faith as worldly as the Creole amalgam which became known as Santería.

Some ethnographers have described Santería as cultural masquerade. Yoruba slaves “converted” by their masters simply figured out which saint seemed closest to which god and dressed one in the other’s clothing. This is certainly true, but things were more complex than that. Even before the Yoruba religion reached the New World it was a mix of Egypt, Greece, Jerusalem, and Africa. Once in Cuba not only did Spain’s Catholicism enter in, but that country’s tradition of spiritism and gypsy magic as well.

Santería became a wellspring of Cuba’s baroque imagination and a reminder of magic and earthly delights during those years when the island was most driven by collective, even ascetic values. “ ‘The religion,’ as Santería is called on the island, was always there, always palpable, an alternative pulse,” says Cuba’s National Institute of Science psychologist Elena Suarez. Monsignor Carlos Manuel de Cespedes, Vicar of the Catholic Church in Havana, goes further. “One simply can’t understand Cuba without understanding Santería,” he says.

I was returning to Cuba for the fourth time in five years and trying to decide which of two friends to visit first: Elena Suarez, a psychologist who had spent the better part of a lifetime trying to come to terms with the religion, or Juan BenComo, who not only practiced it but made the sacred drums said to call down the gods.

I ended up not even stopping at the hotel before going to BenComo’s home. Within the hour, as usual, he was walking me through Havana. I was seeing it again after a year: the maze of columned walkways, the bodegas strewn with Florentine tile, valentines, and little else, the lovers pushed against wrought-iron fences, the laundry and the filigree.

By noon, we’d reached the toque. I knew on my first day back BenComo would bring me where I could greet the gods. A central sacrament in Santería, a toque is more like a party than a mass. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of them take place in private homes in Havana every weekend. Teams of musicians beat out complex polyrhythms. Those gathered together dance to the rhythms. Sacred stories—gospels— are being relived in that dancing and in the polyrhythms themselves. Sooner or later somebody falls into a trance, “mounted” by a god come to hang out with his community for a while.

We’d been there two hours and still no orisha, as the African gods were called. But the energy was rising. The air seemed to thicken. As usual it was all becoming hypnotic, claustrophobic. The drums wouldn’t stop. I couldn’t tell anymore where they ended and my body began. The place was at a slow boil.

Then a husky young fellow was in convulsions on the ground. Still convulsing, he charged toward the edge of the roof. Six or seven men held him back. I’ve been watching such events for years, but still I find them unnerving. When the young man reappeared about a half an hour later, he’d been dressed by the elders in the orisha Changó’s red-and-white vestments, his face was ashen, his eyes dilated, the possession complete. For eight hours in the tropical sun, the god and his people danced together.

But today the casual ecstasy I was used to seeing was missing. Today the god wasn’t giving his usual advice: where to find an apartment or gasoline, or how to deal with a reluctant lover or a recurrent illness. Again and again Changó called to his community. At one point he fell to his knees pleading for the prayers and sacrifices which would perhaps fortify the pantheon sufficiently to enable them to save Cuba from the civil war they feared was ahead.

I had first come to Cuba as a cultural rather than a political reporter. I was to write on some of the island’s popular bands. That was my pretext. Actually, I’d come on a treasure hunt. My dad had visited the island in 1929. Even forty years after his trip I had watched a rather fearsome man grow soft talking about the light in Cuba, or a musician or feathers and some outrageous flirt. My father had been one of the literally millions of Americans who found their way to Cuba. What was it about the island that captured so many imaginations? Had the revolution, for better or for worse, altered that Cuba beyond recognition? In finding the answers to my questions, like so many before me, I’ve become haunted by Cuba. I’ve returned again and again trying to make sense of what I’ve felt there, most especially of Santería and BenComo.

I first met BenComo at a rumba party. Back in 1988, Cuba’s Union of Writers and Artists could still afford to have them every Wednesday night at its center. That night everybody was getting drunk. Not BenComo, fiftyish and slight, who sat as ever watchful with his periscope eyes. By the time we met, I had come to understand that most of the popular music of Cuba has its roots in the sacred rhythms of Santería and its sister faith Palo, or Kongo. (Ever wondered about the title of that Gloria Estefan song, “The Rhythm is Going to Get You”?) Doing some research into the visual arts on the island, I had seen how much of the work of Cuba’s young painters grew out of Santería’s imagery.

I couldn’t have realized then just how dry BenComo’s response was when I told him I wanted to know more about “the religion.” “Ah, you must be a Marxist then,” he smiled, and proceeded to ask me a series of hard questions about my purpose. The following morning he arrived unannounced at the old Hilton, the Havana Libre, where I was staying, skirted the security police who until recently have tried to keep Cubans and foreigners apart, and with his trademark old-world manners slipped my arm through his. And so began the first of what would be our myriad long walks. Like many Cubans, BenComo doesn’t sit still easily. He walked me all over Havana, teaching Santería all the while.

According to BenComo, Santería is all about balance in the face of life’s constant change. The gods are basic energy patterns. They’re force fields, some wildly erotic, some Christlike, some sullen, all of which must be respected and reconciled. Santería is as much a psychology as a theology. Its ideal: being able to ride the mean in the face of all this energy. (An ideal which, according to Yale Africanist Robert Farris Thompson, created “the aesthetics of cool.”) The gods are quintessentially immanent in Santería. Everything in the world, from stars to stones, is a manifestation of a particular orisha—everything, even color, belongs to one god or another. There simply are no secular objects. Likewise each activity, each profession, each time of day has its guiding orisha. Neither then are there secular moments. Santería teaches that by using sacred recipes—a few herbs belonging to one god, a bit of food belonging to another—by properly administrating the energies of life’s various force fields, it is possible to bring about concrete changes in individual lives—magic. (According to BenComo, the sacred ceiba tree cries when asked to lend its roots to black magic, but the supreme creator, Olofi, gave permission for everything. The ceiba must do as it’s bid, i.e., magic works even if those working it don’t have the ethics to handle it wisely.)

As BenComo and I walked, we didn’t go a block without somebody stopping to greet us. Often we’d be brought home by a friend for coffee. I sat among life-size statues of the orishas—a.k.a. various Catholic saints—in modest living rooms and wealthy ones all over Havana. Over the coffee often there was talk of Santeria’s miracies. An economist spoke of his daughter, diagnosed as schizophrenic. The family consulted the gods via Santeria’s elaborate divination system. She was to be initiated, not institutionalized, the gods advised. That was ten years ago, and according to her father, the girl has had no psychotic episodes since. I heard similar stories of cancers and remissions. There was talk of more modest miracles as well. Havana today is in such disrepair that buildings quite literally are falling down. One Santería priest, a primary-school teacher, told us his orishas whisper about where to turn to avoid falling bricks.

Teams of musicians beat out complex polyrhythms. Those gathered together dance to the rhythms. . . . We’d been there two hours and still no orisha, as the African gods were called. But the energy was rising. The air seemed to thicken. As usual it was all becoming hypnotic, claustrophobic. The drums wouldn’t stop. I couldn’t tell anymore where they ended and my body began. The place was at a slow boil.

On one of our walks BenComo and I ran into Sara Vasquez. She’s an old woman now, but still quite stunning. Ever since she was a girl she’s worked as a model for Cuba’s painters. “The Black Pearl,” she was called in her heyday. When I admired the blue scarf she wore, she winked. The blue belongs to Yemayá, goddess of deep waters, who manages to be extraordinarily seductive without necessarily letting herself be touched. “Nobody can be lost,” Sara told me once. “The gods are so close, you just have to know how to reach them.”

One afternoon BenComo brought me to a ritual party given for the dead, as well as for the orishas, where Richard Edgues, cocreator of the cha-

chacha, played his famous flute for the spirits. After a few hours of sacred rhythms, of trances where sweet old women turned into seers after crawling around the floors in trance, gobbling up the sacred herbs scattered about in the corners, the musicians and the hundred or so attending broke into chachacha. I left wondering if it were possible in Cuba even to separate the secular from the sacred.

Cuban ethnographer Natalia Bolivar estimates that 90 percent of all Cubans practice Santería. That figure may well be high. I did meet intellectuals and bureaucrats who said that they believed in none of this, although almost always they’d add, “but that which can fly, flies.” “Santería has created such a thick atmosphere in Cuba,” added a churchman who prefers to remain anonymous, “that even those of us outside the faith float about in it.”

One day Pedro Vasquez, the brother of my friend Elena, came to tell me about a dream. Pedro was an architect, a man who had believed all his adult life only in Fidel’s New Man. Yet his dream counseled that insulin treatments alone wouldn’t control his daughter’s diabetes. The girl must also scatter the white blossoms and jars of honey sacred to Ochun (the orisha of love and sweetness) around her room. “Is there no escape from this shit?” he asked.

Both Elena and her brother had been forbidden to talk about Santería as they grew up in their prerevolutionary upper-middle-class home. But unlike her brother, Elena has spent her entire adult life colliding with “the religion.” In the 1960s, during the revolution’s early days, while leading literacy programs which reached deep into the Cuban countryside, she heard every day of Santeria’s wonders. “Then one afternoon in the mountains, I saw a procession pass. I swear it was raining only on the hands of those carrying gifts for the gods. Since then I’ve become ever more confounded by Santería.” After Suarez’s work with the literacy campaigns, she was part of the effort to set up cultural networks in tiny towns all over the island. Today she is part of a research unit in Cuba’s National Academy of Sciences that studies the efficacy of Santeria’s “green medicine.” “I’m never really comfortable with Santería,” she says. “It seems we Cubans have some kind of tiger by the tail.”

Seven years ago, on my first trip to Cuba, a singer in a band had introduced us. For all her perfect Spanish manners, Elena can boogie. Fifty-something, too skinny by Cuban standards, with a crazy mane of curls, it was Elena who brought me together with everybody in Havana who in her estimation had thought seriously about “the religion.” We’d talk together long into the night about our lives. My measured friend restored my equilibrium

in Cuba far more often than she knew. Still, for reasons I don’t completely understand, I never introduced her to BenComo. Neither did I tell her what went on between us. I’m not talking romance. There was none. Neither did any money change hands. To this day I don’t understand why BenComo ever adopted me or why from the first I was willing to accompany him not only on walks but on buses—for buses were still running seven years ago—over much of the island.

Still, it took BenComo most of that first trip to convince me to go ahead with the sacrifice. Every priest with whom we had talked apparently had seen the crisis in my immediate family. In such circumstances a sacrifice—returning to life some of the energy living a life has taken away—is often said to be appropriate, even necessary. I wouldn’t consider it. But finally, after a few weeks with BenComo, fascination won out.

Using a journalist’s justification, I stood with BenComo and two more Santería priests, waiting for a bus, live chicken in hand. Nobody looked at us twice. It was a hot, clear day. We were down on the rocks by the bay in no time. Fishermen were casual with their greetings. We searched together for an appropriate “sacred” stone. Changó’s lightning began at the same time as the priests’ prayers. A wind came up as I joined in. The sky got darker and darker. The water began pulsing, pulsing like the innards of something, pulsing like a drum, a convulsion, an orgasm. All of us were kneeling now. In one quick stroke, one of the priests had cut the animal’s throat. As blood washed over the stone, the sky and water turned silver. Only when the chicken was out to sea did Changó’s rains come. Back in the hotel, I downed more than one tranquilizer.

The sky got darker and darker. The water began pulsing, pulsing like the innards of something, pulsing like a drum, a convulsion, an orgasm. All of us were kneeling now. In one quick stroke, one of the priests had cut the animal’s throat. As blood washed over the stone, the sky and water turned silver. Only when the chicken was out to sea did Changó’s rains come.

Suffice it to say, during those early weeks with BenComo I was nervous. A Cuban, a devoted Marxist, once asked me if I ever prayed. God knows, I’ve wanted to, but the symbols of my own tradition have seemed bone dry. The poetry of William Blake seemed like prayer to me. And BenComo’s world at times seemed close to Blake. Yet during much of that first trip, I don’t know who I was more suspicious of: myself or BenComo. Was I after exotica? And who exactly was this fellow at my side? Occasionally as we walked he’d hum a line from an old chachacha. “Que quiere el negro, Mami?”—What does the black man want, Mommy?

Elena Suarez was full of stories of how deeply Santería and its sister faiths have penetrated the island’s history—at least according to popular imagination. Cuba’s strong man of the 1930s, dictator Geraldo Machado, allegedly buried a prenda—a sort of magic stick— beneath a ceiba tree in Havana’s Central Park to avenge himself on his people. According to ethnographer Natalia Bolivar, such stories are far from rumor. She points to the multi-million-dollar collection of gold and silver sacred objects still in the hands of the widow of Rogelio, one of prerevolutionary Cuba’s most important Santería priests. Bolivar claims these were the gifts of Carlos Prio, Cuba’s last democratically elected president, and General Fulgenio Batista, whose coup toppled Prio as Fidel’s revolution would topple Batista. “Yet before the revolution,” she says, “Santería was kept in the shadows—at least among the oligarchy [which included Bolivar’s family].” Many of Cuba’s rich and powerful may have had their Santería priests, a whole island may have been dancing to Santería’s rhythms, yet according to Bolivar prerevolutionary Cuba insisted on seeing itself as white, Catholic, and Spanish.

And after the revolution? There were Santería initiates in Fidel’s inner circle. That much is certain. Fongtime confidant Celia Sanchez was one. (Curiously many Cubans feel it was when Celia died in the early 1980s that Fidel began to lose touch with Cuba.) But what about the myriad rumors that Fidel himself is an initiate? Many of his friends and foes alike agree upon the name he received at that alleged initiation: “He who survives, king for all his days.”

“Communist Cuba’s relationship with Santería was convoluted at best,” says a Havana University historian. “Fidel couldn’t resist playing with it even as he tried (at least initially) to break it. State attacks were subtle. Santería itself was never banned, but especially early on permissions for toques were so regularly denied that it became difficult at best to practice the religion—at least openly. Those who did receive permission were often those working for state security as informers. Meanwhile, 1960s media campaigns were insinuating that members of these religions were criminals or social deviants.” According to many of those I met at toques, at various times in revolutionary Cuba, if parents were found to have initiated a child that parent would be jailed for weeks or months. One old woman took me aside. “I was his legs,” she said, referring to her husband, a Santería priest. “During the hardest times when it was too dangerous for Maximo, I would go out into the night. Sometimes I’d be out many hours but I always came home with the herbs Maximo needed. Or the animals. It was me who said the prayers to the ceiba. I was his legs.” Until relatively recently, the party line on Santería went something about it being born out of the desperation of the poor, and that as a religion it would simply “fade away, outgrown once the revolution’s social-service networks had done their work.” Often a Party member would wink then and add: “One or the other has to go—it’s us or them.”

All the while postrevolutionary Cuba tried to use Santería to forge a politically correct national identity, one which would turn away from the legacy of white “imperialist” Spain and the developed world, one which would not incidentally further confirm Fidel as the leader of the third world. In the early 1960s, three Santería museums were opened in the Havana vicinity alone. Children were taken to them on school trips. The Ministry of Culture let it be known that Afro-Cuban themes in the arts would be appreciated. And the island’s most popular dance band, Fos VanVan, began working lyrics into their songs which married Afro-Cuban religions and revolutionary consciousness. (In one song, all of Central America’s guerrilla wars are described as unstoppable, as close to nature’s secrets as is Santería’s sister faith, Palo.) Meanwhile, something unexpected was happening. The revolution’s cultural and educative networks were so good and so extensive that a whole new class of artists was being produced. Many of these artists were poor or from rural areas. Their themes brought an explosion of Santería into Cuban high culture. (Feaving aside Santeria’s profound influence on Cuban music and dance, few prerevolutionary artists would touch its themes. Novelist Alejo Carpentier and painter Wifredo Lam are the two most notable exceptions.)

Today Cuba is “a country very nearly obsessed with its magical side,” says José Bedia, one of the island’s premier young painters. According to a librarian at the University of Havana, no matter the quality of book the revolution prints on Santería, it’s sold out in less than a week. Nearly every volume on Santería that any library has had in its collection has been stolen.

All week BenComo had been reminding me that we were expected in Guanabacoa, a small town across the bay from Havana, early on Sunday afternoon. This was to be a double toque, with six drums instead of the usual three. He thought it was something I should see. There were already five Ochuns present when BenComo and I arrived. One of them would nuzzle a devotee and it would all begin again: another possession/trance, another Ochun incarnated. There was no end in sight. Each orisba has dozens of caminos (roads), variations on a single theme. A handful of them danced together here. They seemed to have a strange pull on one another, these pieces of the goddess. A move from one necessitated a move from another. And for the initiated, each move told a story. I would have expected something more lyrical from the goddess of beauty. These dances were desperate: the hunted keeping a watch. Still, the possessed, tall, thin men mostly (the gods/goddesses aren’t particular about possessing those of the corresponding sex) shimmered in Ochim’s gold cloth. I kept trying to shake off energy. Too much had seeped inside. Perhaps with enough dancing, a climax, a release would come. But I stood there frozen, caught between worlds.

“Stay away from all this,” a correspondent covering Cuba for one of the State’s prestigious newspapers warned me. “If I really gave in to those drums,” he says, “my life would change in ways I can’t begin to know. Better to leave it all alone.” “Stay away from all this,” echoed my friend Elena Suarez. “I’ve seen what happens to my friends. Santería becomes an addiction.”

Still I couldn’t seem to take anybody’s advice. Granted there was plenty to disturb me in Santería. Blood sacrifices were the least of it. As Elena suggested, this is a world so full of meaning, with so many signs and messages, that finally one can become paralyzed, unable even to cross a street without incantations. There’s so much paranoia in Santería, especially in today’s Cuba. A run of bad luck is almost always considered active intervention—the magic of one’s enemies. (Perhaps this is the underside of a culture so given to intimacy.) Besides, I grew tired of priests whose religiosity was often all about how much the gods could do for them and how quickly. “In many ways Santería is the perfect paradigm for Cuba’s notorious practicality,” anthropologist Virgilio Moreno told me. “Santería isn’t so simple,” countered devil’s advocate Monsignor Carlos Manuel de Cespedes. More than once he reminded me, “Within the religion you can find every kind of faith.” Psychologist Isabel Sanchez put it another way. “Cuba’s soul,” she said, “is always caught between poles. You’ll never find one tendency here without its opposite. Santería is at least as much a paradigm for Cuba’s idealism as its practicality.” (I thought of those huge revolutionary posters displayed everywhere in Havana. All of them are wordplays on “faithfulness.”)

Elena Suarez may have warned me away from Santería—“Frankly, I’m afraid of it,” she’s said. Yet paradoxically my friend describes the religion as “underpinning the deepest stratum of Cuban culture, marking even the way we think. Santería,” she says, “has created a whole island fascinated by magical transformation. You can hear it in our music.” “Even the youngest children here have a need to transform themselves,” psychologist Isabel Sanchez notes. “It’s part of a whole cluster of spiritual concerns that penetrate everything from the political to the cultural life of Cuba.” “We Cubans,” adds poet Omar Perez, “have a need not so much to be different from one another but to be able to move easily in and out of ordinary reality.” “Just look at Cuban women’s obsession to reverse their hair color,” says Minerva Lopez, a hairdresser and painter whose work focuses on Afro-Cuban gremlins. Perhaps Politiboro Chief Jose Carniedad put it most succinctly. A few months before his death he rather grudgingly told me, “To be human, at least in Cuba, seems to indicate a magical sensibility.”

BenComo has little patience with such theorizing. Instead he teaches me the sacred dances said to call down Santeria’s gods. There’s Ogún, lord of iron, lord of Thanatos—his movements are more frenzy than dance. And Yemayá, goddess of deep waters— during her dances one’s back seems somehow open to the ocean.

And Changó, lord of lightning and just cause—during these sequences, one hand indicates the testicles, the other throws the lightning bolts which are said to originate from his testicles. Dance these dances and any theory about the religion pales. Perhaps more than anything else, Santería is about imprints on the body. I spoke once with Alicia Alonso, a former Balanchine soloist who heads Cuba’s National Ballet. “Our genius as Cubans,” she told me, “is our ability to communicate with our bodies.”

For over half a century, psychologists such as Carl Jung have been writing about our culture’s need to reconnect the primal with the divine. Humanist Joseph Campbell describes the symbols of the Afro-Caribbean faiths which do just that as “luminous.” Here in the States, our answer has been Robert Bly’s weekend adventures and New Age retreats. Obviously in Cuba something far more organic is going on. I’ve wondered if it isn’t the underworld of Santería that makes Cuba as haunting as it is. I’ve wondered if a glimmer of all this—best described perhaps as body as soul— doesn’t explain why my dad and so many other U.S. tourists found their way here.

“We Cubans do indeed believe too easily in too much,” says Monsignor Carlos Manuel de Cespedes. “It may be heresy to say so, but I wouldn’t have it any other way. At least my people are able to feel excitement. At least my people are able to feel.” I thought of all the couples I’d seen at dance halls—a good number of them octogenarians—dancing to rhythms so close to those sacred to Santería, couples who couldn’t seem to get out of each other’s arms.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

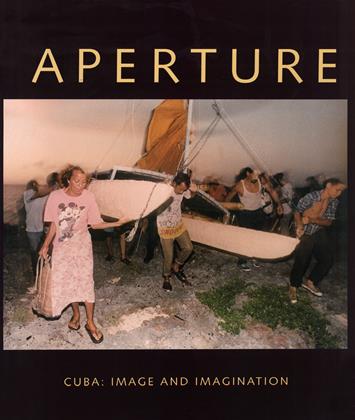

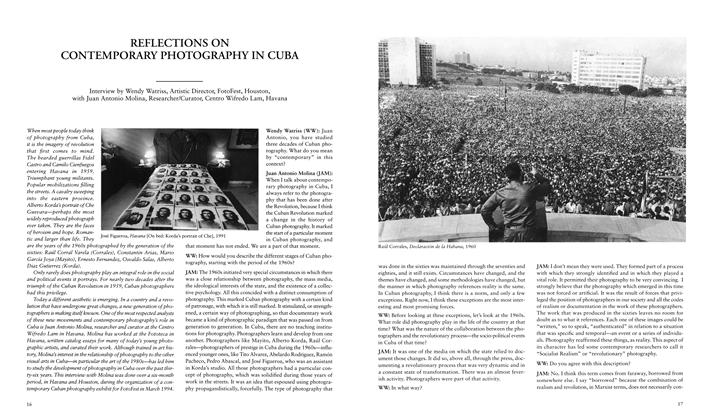

Reflections On Contemporary Photography In Cuba

Fall 1995 By Wendy Watriss -

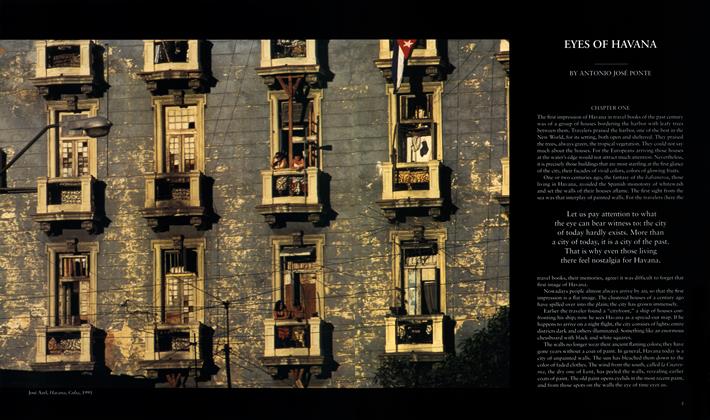

Eyes Of Havana

Fall 1995 By Antonio José Ponte -

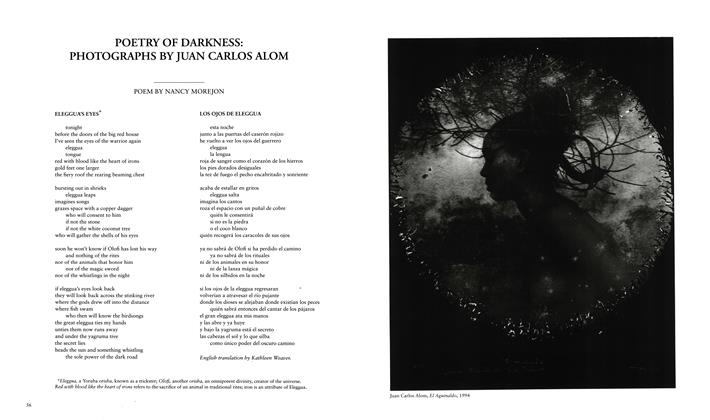

Poetry Of Darkness: Photographs By Juan Carlos Alom

Fall 1995 By Nancy Morejon -

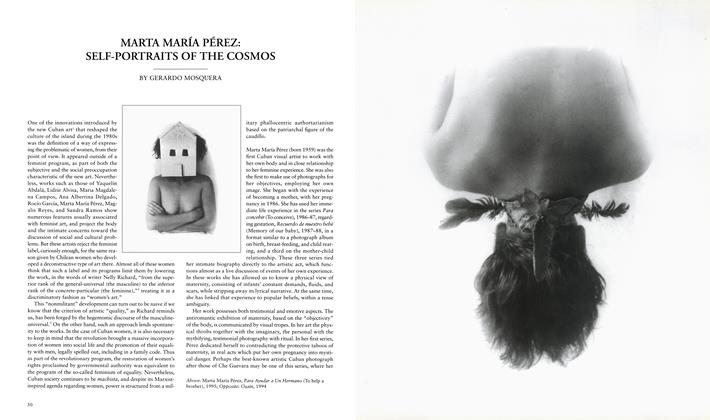

Marta María Pérez: Self-Portraits Of The Cosmos

Fall 1995 By Gerardo Mosquera -

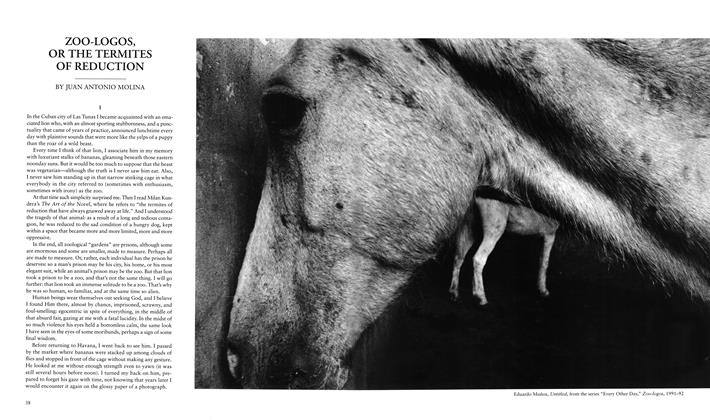

Zoo-Logos, Or The Termites Of Reduction

Fall 1995 By Juan Antonio Molina -

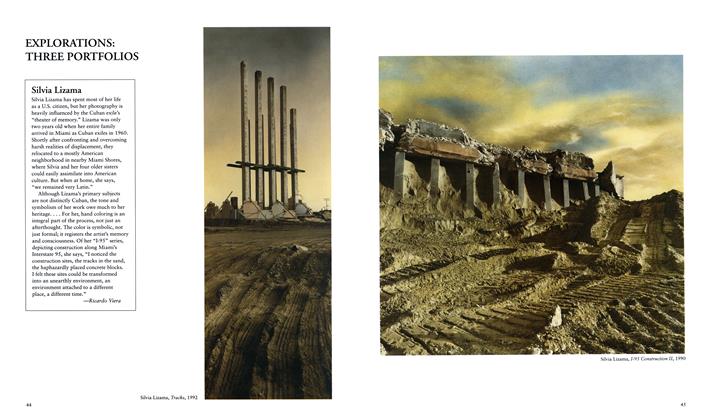

Explorations: Three Portfolios

Fall 1995 By Ricardo Viera