CREATING A VISUAL HISTORY: A QUESTION OF OWNERSHIP

THERESA HARLAN

PHOTOGRAPHS BY LEE MARMON AND MAGGIE STEBER

In 1992 I guest curated "Message Carriers: Native Photographic Messages" for the Photographic Resource Center at Boston University.1 When invited, I could not accept without careful consideration of significant issues such as: ghettoization, opportunism (mine and theirs), and exploitation. Mainstream museums and publications often set apart “artists of color,” “multicultural artists,” and “ethnic artists,” thereby designating us as the “other” or “different.” The art and writings of these “other” artists are locked into discussions of “their” art, “their” people, and “their” issues. While there are still few opportunities to exhibit works by Native artists, there are even fewer exhibitions that treat these works in terms of their intellectual and critical contributions. Contemporary Native art is often characterized as angry, created from the voices of the defeated, and confined to the realm of the emotions.

Native people have—but are not perceived as having—diverse histories, cultures, languages, economics, politics, and worldviews. As Native people, we must claim rights to, and ownership of, strategic and intellectual space for our works. We must reject the reduction of Native images to sentimental portraits, such as those depicted by Marcia Keegan in her book Enduring Culture: A Century of Photography of the Southwest Indians.2 Keegan writes, “From the beginning of my acquaintance with them, it was the Indians’ confidence and attunement to the eternal verities that inspired my wonder and admiration. Thus it became my enduring commitment to try to experience, imagine, and document that more elusive subject, the traditional Indian way of life.”3 This type of thinking reduces Native survival to a matter of nostalgia, and precludes discussion of the political strategies that enabled Native survival. The writer bell hooks refers to nostalgia as “that longing for something to be as once it was, a kind of useless act. . . .”4 and calls for the recognition of the politicized state of memory as “. . . that remembering that serves to illuminate and transform the present.”5

Native survival was and remains a contest over life, humanity, land, systems of knowledge, memory, and representations. Native memories and representations are persistently pushed aside to make way for constructed Western myths and their representations of Native people. Ownership of Native representations is a critical arena of this contest, for there are those who insist on following the tired, romantic formulas used to depict Native people. Those myths ensure an existence without context, without history, without a reality. An existence that allows for the combing of hair with yucca brushes in the light of a Southwest sunset; competition powwow dancing reborn as a spiritual ceremony; or the drunken Indian asleep on cement city sidewalks unable to cope with the white man’s world. These are the representations constantly paraded before us by nonNative photographic publications such as Keegan’s Enduring Culture, or National Geographic’s 1994 issue on American Indians, or Marc Gaede’s Border Towns. Such constructed myths and representations are given institutional validation in the classroom and are continually supported by popular culture and media.

American classrooms are usually the first site of contest for Native children. In her essay, “Constructing Images, Constructing Reality: American Indian Photography and Representation,” Gail Tremblay writes, “When Native children are taught that they are not equal, that their cultures are incapable of surviving in a modern world, they suffer from the pain that has haunted their parents’ lives, that haunts their own lives. For an indigenous person, choosing not to vanish, not to feel inferior, not to hate oneself, becomes an intensely political act. A Native photographer coming to image making in this climate must ask, ‘What shall I take pictures of, who shall I take pictures for, what will my images communicate to the world?”’6

Photographer and filmmaker Victor Masayesva, Jr., has described the camera as a weapon. “As Hopi photographers, we are indeed in a dangerous time. The camera which is available to us is a weapon that will violate the silences and secrets so essential to our group survival.”7 Writer, curator, and photographer Richard Hill, Jr. of the Tuscarora nation, also named the camera as a weapon, but a weapon for “art confrontation rather than military confrontation. Indians themselves now have taken the power of the image and begun to use it for their own enjoyment as well as for its potential power as a political weapon.”8 Artist Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie declared, “No longer is the camera held by an outsider looking in; the camera is now held with brown hands opening familiar worlds. We document ourselves with a humanizing eye, we create new visions with ease, and we can turn the camera and show how we see you. The power of the image is not a new concept to the Native photographer—look at petroglyphs and ledger drawings. What has changed is the process.”9

Masayesva, Hill, and Tsinhnahjinnie speak from the experience of seeing themselves spoken for by outsiders, of seeing the surreal positioned as the real. As Trinh T. Minh-ha says, Native image-makers “understand the dehumanization of forced-removal/relocation/reeducation/re-definition, the humiliation of having to falsify your own reality, your voice—you know. And often cannot say it. You try and keep on trying to unsay it, for if you don’t they will not fail to fill in the blanks on your behalf, and you will be said.”10

When Native people do pick up the camera, often their image making is greeted with a patronizing welcome. The “Indian” no longer sits passively before the camera, but now operates the camera—a symbol of the white man’s technology. The voices and images of Native photographers must be understood as rooted in and informed by Native experiences and knowledge.

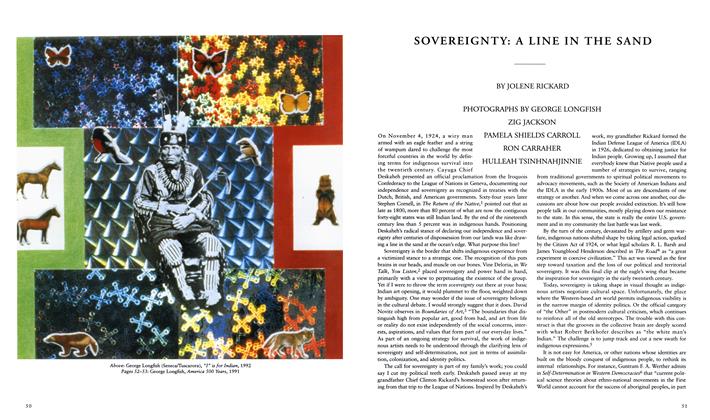

Lee Marmon has created, and continues to create, photographic representations of Native people that affirm Native memories, self-knowledge, and presence. Upon his return from World War II, Marmon began taking photographs of the old people in the villages at Laguna Pueblo—so that there would be something to remember them by. Marmon’s photographic remembrances are of a generation of people who had to devise ways to affirm and protect Laguna knowledge despite the pernicious attempts—beginning in the sixteenth century—of the Spanish, Mexican, and later, the United States governments to strip them of land, culture, religion, and the memory of that existence. Thus, these are not merely images of cute old people. The presence of Juana Scott Piño; of Jeff Sousea in White Mans Moccasins; or of Bennie at the sheep camp might at first seem ironic or contradictory, as some are dressed in “traditional” clothing and others not. Marmon’s photography is not confined to any strict notion of Indianness. It differs vastly from Keegan’s inspired commitment to document the “elusive traditional way of life,” as these images include the context of Laguna lives and experiences. Marmon did not drive around seeking the best adobe wall to use as a background; he photographed his community while delivering groceries for his family’s store.11 What we see through Marmon’s photographs are images of people living and working as they are—and without an implied mystical “elusiveness.” Marmon’s title, White Mans Moccasins, is more than the irony of an old Laguna man wearing high-tops. It is Pueblo objectification of Western society through the appropriation of a popular Western icon.

Marmon’s images are of people who do not perceive themselves as confined to any mythic or imagined concepts held by others. They remain fresh because they are not restricted by essentialist notions that Native people must dress as Natives in order to look Native and to be Native. Even some Native documentary photographers fall prey to expressing Native thinking and traditions through what is worn. By doing this, they risk entering into the same trap of only being able to recognize themselves through the eyes of non-Natives.

Zig Jackson provides ethnographic material about non-Native practices in photographing Native people in his series “Indian Photographing Tourist Photographing Indian.” The tourists he records are so intent on their subjects and the drama of the moment that they are unaware of Jackson’s presence. They exhibit a fascination usually reserved for movie stars, rock stars, scandalized politicians, or famous athletes. For these photographers, the value of Native images is based strictly on appearance. But would they clamor to take pictures of Native people wearing the clothes they wear at school, work, or home? No. Because when Native people wear bright colors, fringe, beads, leather, and feathers, they are “real” Indians. When they are dressed in everyday clothes they are not. Robert Berkhofer, Jr., discussed this in The White Man's Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present. “Since Whites primarily understood the Indian as an antithesis to themselves, then civilization and Indianness as they defined them would forever be opposites. Only civilization had history and dynamics in this view, so therefore Indianness must be conceived as ahistorical and static. If the Indian changed through the adoption of civilization as defined by Whites, then he/she was no longer truly Indian according to the image, because the Indian was judged by what Whites were not. Change toward what Whites were made him [her] ipso facto less Indian.”12

Larry McNeil deliberately avoids representations of the “feathered” Indian and instead chooses a single feather to discuss Native survival. Some critics have described this work as relying on an easily recognized symbol, even a cliché. In fact, to reduce McNeil’s use of feathers to a cliché is to accept the dominant thinking that is continually wielded against Native people. (Dominant thinking prevails when Native symbols are reduced to cliché while American colonization continues to be described as Manifest Destiny.) In McNeil’s series, Native survival deliberately is not shown through full-color images of powwow dancers. Instead, he keeps to the visceral side of survival through black-and-white depictions of worn and broken feathers set against a dark background. Here, the Native memory of survival is neither romantic nor nostalgic.

James Luna’s photo-essay “I’ve Always Wanted to Be an American Indian,” is a satirical jab at those who at some point discover a thread of Native ancestry in their past and then draw on myths of Indian identity to realize their ancestral inheritance. Luna’s wake-up call is for these individuals to realize the reach of racist, political, and economic subordination of Native people, who cannot pick and choose their Native circumstances. Luna escorts the wake-up Indian on a guided tour of his La Jolla reservation, pointing out interesting sites and bits of information. His snapshot photographs of the mission church, schoolchildren, and a disintegrating adobe building are combined with positive and negative snips of information. Statements such as “During the last five years on the Reservation there have been and/or are now: three murders, an average unemployment rate of 47 percent, . . . twenty-one divorces and/or separations . . . thirty-nine births, forty-five government homes built ... an increase in the percentage of high school graduates.”13 At the end of the tour, Luna asks “Hey, do you still want to be an Indian?”

Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie reveals the current dispute among Native people over who, in fact, is “Indian.” Tsinhnahjinnie’s Would I Have Been a Member of the Nighthawk, Snake Society or Would I Have Been a Half-Breed Leading the Whites to the Full-Bloods, signed “111-390” (her issued tribal enrollment number) uses selfportraiture to discuss identity politics within a historical context. These graphic, 40-by-30-inch, black-and-white head-and-shoulder shots, which resemble passport or police photographs, support her discussion of the use of photography to identify and control the “other.” The reference to the Nighthawk, Snake societies, and halfbreeds comes from a 1920 statement made by Eufala Harjo regarding the practice of the Bureau of Indian Affairs of securing names of Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Cherokee resistance-group members from “half-breed” informants.14 Societies were formed to resist tribal leaders’ decisions to ignore previous treaty agreements and to accept the 1887 Dawes Allotment Act, which reallocated parcels of lands to individual ownership—thereby overturning tribal practices of land collectively held through the maternal line.

Tsinhnahjinnie is one of the few artists who have taken a public stand on the 1990 Indian Arts and Crafts Act, which requires tribal enrollment numbers, state census roll numbers, or a special “Indian artist” status to be provided by an artist’s tribal council in order for Native artists to sell their work as “Indian” art. Tsinhnahjinnie reminds us that we, as Native people, must recognize and understand identity politics as the invention of the United States government.

Jolene Rickard’s Sweka and PCBs calls our attention to the fact that we may be ignoring or underestimating the dangers that accompany moneyed solicitations of tribal land use for toxic dump sites that contaminate food sources. Rickard draws a connecting line from toxic contamination to the gathering, collecting, fishing, and hunting of foods, and the ritual ceremonies that emanate from those sources. Rickard warns us, “If Indians no longer have a material and spiritual relationship with ‘land,’ then certain teachings and ceremonies cannot take place. Even when it is possible to transform these teachings into abstract space, without the geographic place of community, experience has shown that the teachings increasingly dissipate.”15

Sweka and PCBs is not a romantic representation of an Indian man and his relationship to the natural world. It is a warning for all of us to confront our own threatened survival as human beings. We may become our own endangered species along with the salmon and the eagle that feeds on the salmon.

In Pamela Shields Carroll’s Footprints, family images are printed on cut-out soles of baby moccasins, along with porcupine quills, collected in a small wooden box. Footprints evokes family memories that ultimately inform the next generation. The image on the left sole is of Carroll’s brother celebrating his third birthday, dressed as a cowboy, sitting on a pony. The right sole depicts Carroll’s greataunt’s Sun Dance tipi. Footprints is layered with personal memories, but also speaks from historical experience. It is a sister’s quiet memory of her brother—and a statement about non-Mative influences. The complexity of growing up Native is revealed in a family snapshot, in which her brother, as a child, adopts the dress of those who were part of the conquest of his larger Blackfoot family. It is also a memory of family participation and responsibility in ceremony, and the health of a community through the Sun Dance. Yet together the moccasin soles represent diverse paths: the left, reflective of outside influences and future generations; the right, inside sources of knowledge and the integrity of Blackfoot culture.

(continued on page 32)

Creating a visual history—and its representations—from Native memories or from Western myths: this is the question before Native image-makers and photographers today. The contest remains over who will image—and own—this history. Before too many assumptions are made, we must define history, define whose history it is, and define its purpose, as well as the tools used for the telling of it. The intent of history is to help us keep our bearings. That is, to know what is significant and, most importantly, to teach us how to recognize the significant. What happens when history is skewed, or when we no longer have the same skills of recognition? We as human beings become disabled by the inability to distinguish what is real from what is not. Gerald Vizenor, in his book Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance, calls this “Postindian simulations [which] are the absence of shades, shadows, and consciousness; simulations are mere traces of common metaphors in the stories of survivance and the manners of domination.”

What Native photographers provide is the possibility of a Native perspective unclouded by white liberal guilt or allegiance to Western heroes. Yet these possibilities are not guaranteed by race or genetics. For if the photographer picks up his or her camera and approaches image making with the same notions of capturing a “proud/primitive” moment, then we are not getting a Native perspective. We are seeing Euro-American image-making traditions in action in Native hands. Those images do not carry messages of survival. In fact they are an ominous signal that colonization has been effective, in that the “Indian” can now recognize himor herself only through the outside, as an outsider.

(continued from page 26)

Native image-makers who contribute to self-knowledge and survival create messages and remembrances that recognize the origin, nature, and direction of their Native existence and communities. They understand that their point of origin began before the formation of the United States and is directly rooted to the land. These Native image-makers understand that the images they create may either subvert or support existing representations of Native people. They understand that they must create the intellectual space for their images to be understood, and free themselves from the contest over visual history and its representations of Native people.

1. Gail Tremblay, “Constructing Images, Constructing Reality: American Indian Photography and Representation” in Views: A Journal of Photography in New England (Vol. 13-14, Winter 1993), p. 30.

2. “Message Carriers: Native Photographic Messages” was at the Boston Photographic Resource Center at Boston University in October, 1992. The exhibition included the works of Patricia Deadman, Zig Jackson, Carm Little Turtle, James Luna, Larry McNeil, Jolene Rickard, Hulleah Tsinhnahjinnie, and Richard Ray Whitman. Then staff curator Anita Douthat initiated the exhibition. The PRC was instrumental in the success of the exhibition.

3. Marcia K. Keegan, Enduring Culture: A Century of Photography of the Southwest Indians (Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 1990), p. 11.

4. bell hooks, Yearning, Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics (Boston: South End Press, 1990), p. 147.

5. Ibid

6. Tremblay, p. 30.

7. Victor Masayesva, Jr., “Kwikwilyaqua: Hopi Photography,” in Hopi Photographers/ Hopi Images, edited by Larry Evers (Tucson: Sun Tracks, University of Arizona Press, 1983), pp. 10-11.

8. Richard Hill, Jr. quoted in Susan R Dixon, “Images of Indians: Controlling the Camera,” in North East Indian Quarterly (Spring/Summer, 1987), p. 25.

9. Hulleah J. Tsinhnahjinnie, “Compensating Imbalances,” in Exposure 29 (Fall 1993), p. 30.

10. Trinh T. Minh-ha, Women Native Other: Writing Postcolonialilty and Feminism (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1989), p. 80.

11. Lee Marmon owns and manages the Blue Eyed Indian Bookshop at Laguna Pueblo.

12. Robert Berkhofer, Jr., The White Man’s Indian: Images of the American Indian from Columbus to the Present (New York: First Vintage Books Edition, A Division of Random House, 1979), p. 29.

13. James Luna, Art Journal (Vol. 51, No. 3, Fall 1992), pp. 23-25.

14. For further discussion see Angie Debo’s A History of the Indians of the United States (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1990).

15. Jolene Rickard, “Frozen in the White Light,” in Watchful Eyes: Native Women Artists (Phoenix: Heard Museum, 1994), p. 16.

16. Gerald Vizenor Manifest Manners: Postindian Warriors of Survivance (Hanover, N.H. and London: Wesleyan University Press, University Press of New England, 1994), p. 53.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Words

WordsSovereignty: A Line In The Sand

Summer 1995 By Jolene Rickard -

Ghost In The Machine

Summer 1995 By Paul Chaat Smith -

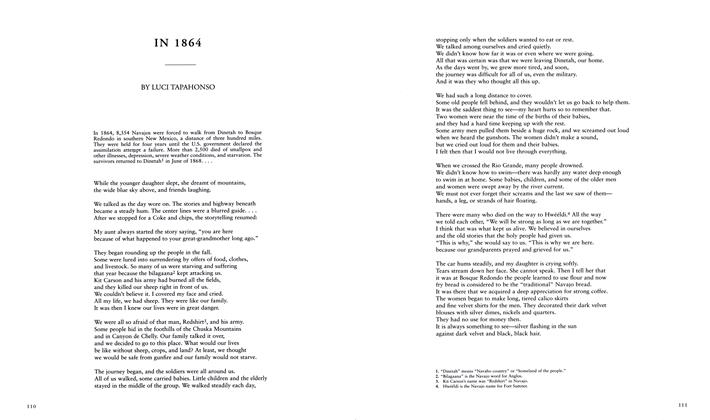

In 1864

Summer 1995 By Luci Tapahonso -

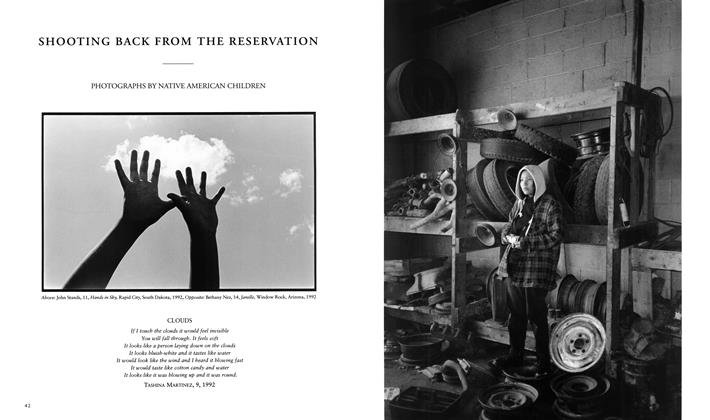

Shooting Back From The Reservation

Summer 1995 -

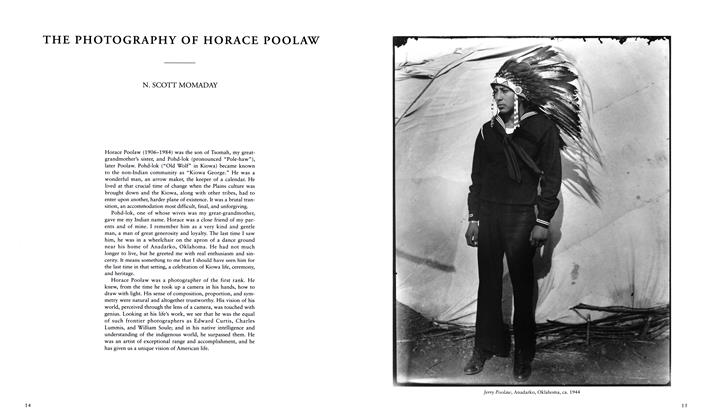

The Photography Of Horace Poolaw

Summer 1995 By N. Scott Momaday -

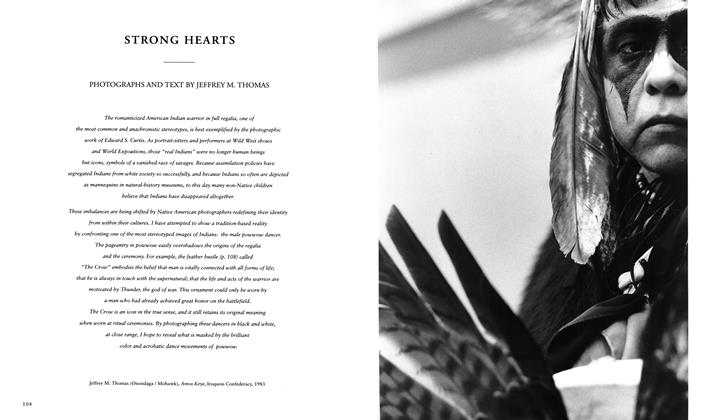

Strong Hearts

Summer 1995 By Jeffrey M. Thomas