APERTURE

Editor's Note

A FEW MONTHS BEFORE HIS DEATH in 1976, Paul Strand wrote: "I think of myself fundamentally as an explorer who has spent his life on a long voyage of discovery."

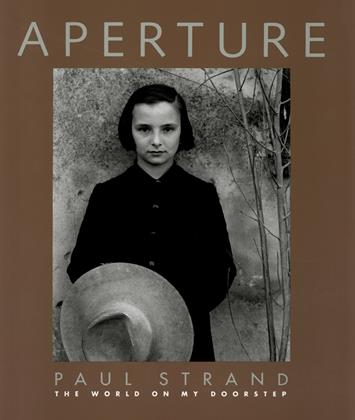

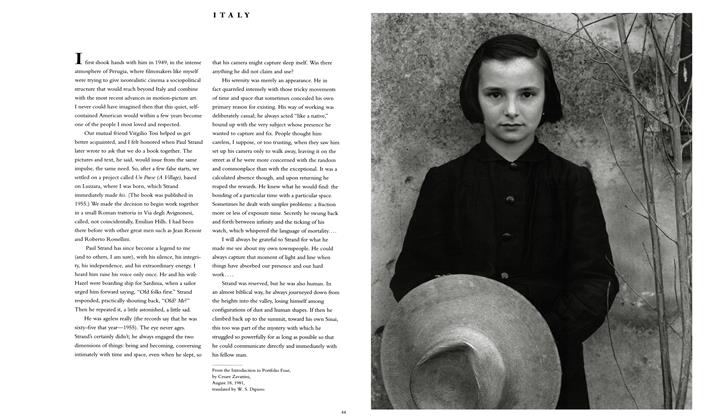

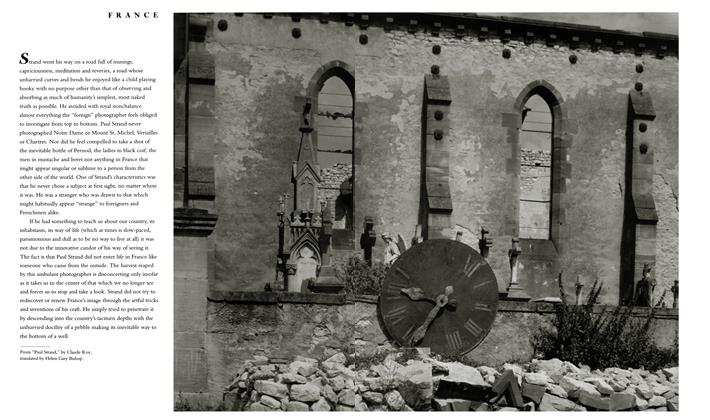

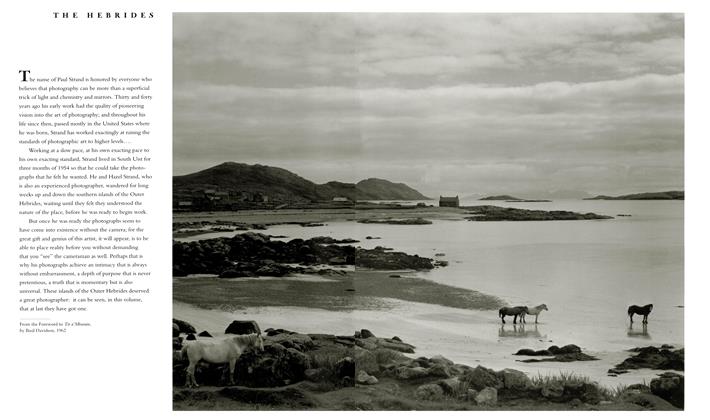

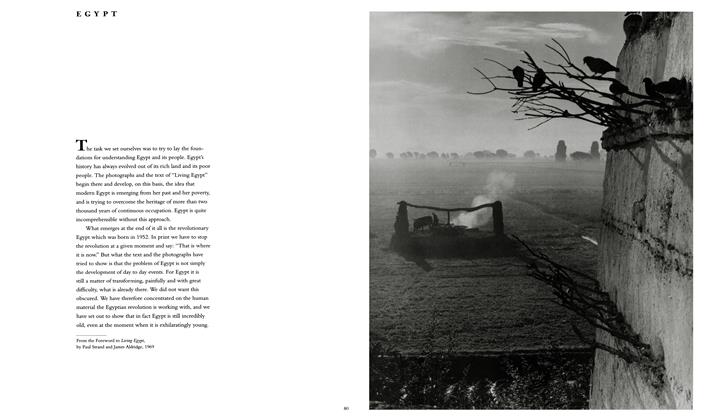

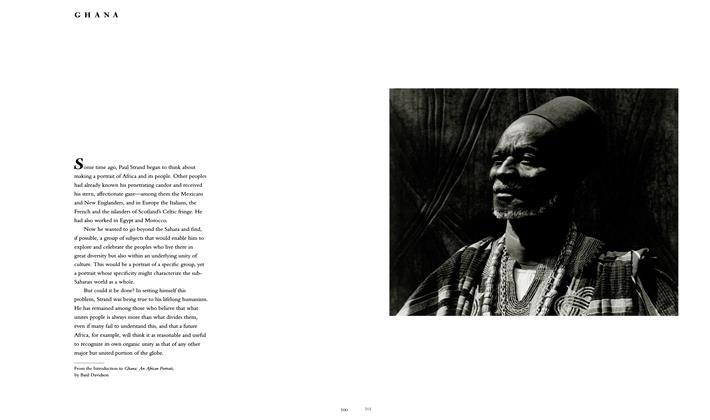

This issue of Aperture embraces the last twenty-five years of Paul Strand's discoveries—from 1950, when he expatriated to France from the McCarthyism of the United States, until his death in 1976. Geographically, his explorations ranged farther than any he had previously undertaken: Paul and his wife Hazel Kingsbury traveled throughout France and to other places in*cluding Italy, Romania, the Hebrides, Morocco, Ghana, and Egypt during this period. Photographically, one begins to discover an almost unearthly wisdom in his work that grasps at mysteries of human experience.

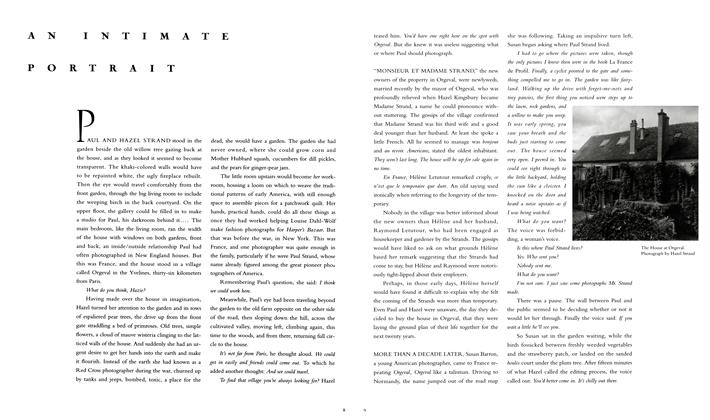

In Strand’s portraits, both the photographer and his subject are free of self-consciousness, and qualities are revealed that are pure, detached—existing beyond the moment. Young Boy, Gondeville, France, 1951, has provoked every conceivable interpretation. After forty years as one of the world’s best-known portraits, that boy’s scowl remains as unfathomable as the Mona Lisa's smile. In other portraits, both individual and group, association of place, history, and the triumphs and pitfalls of life transcend superficial identity.

The iconographie nature of the portraits carries over into studies of landscapes, villages, even machinery. These resonate with a passion for what Paul called “dynamic realism,” and embody his and humanity’s ancient faith in change for the better and the growth of human freedom. These images offer no conclusion; instead there is a sense of the ineffable and a rare sense of grace that can be universally experienced.

Paul Strand’s images, for all their lucidity, beckon us with enigmas, which is why the intent of this issue of Aperture is more inquiring than elegiac. Strand was one of the great explorers in twentieth-century art. That does not mean he was a helpful guide. He believed the viewer must find his own way within the image, an experience that would be unique to each individual, and would evolve over time—given sufficient patience and perseverance.

Our individual voyages of perception provoked by Paul Strand’s photography are enhanced here by the sensitive reminiscence by Catherine Duncan—a friend and trusted colleague of the Strands almost from the moment they arrived in France. And our journey is further facilitated by the accompanying exhibition of “Paul Strand: The World on My Doorstep,” co-curated by Anthony Montoya, director of the Paul Strand Archive, and Michael E. Hoffman, Executive Director of the Aperture Foundation. The show will travel throughout Europe beginning in April 1994 at the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Germany, under the direction of Ute Eskildsen.

In Strand’s last photographs, there is a prevailing sense of time and mortality. Fall in Movement, The Garden, Orgeval, 1973, the frontispiece of this issue, is a mysterious icon filled with decay, death, and implied renewal. The poetic correlative can be found in a writer who inspired Strand throughout his fife. The closing poem in Edgar Lee Master’s Spoon River Anthology, “Webster Ford,” is in fact a hymn to Apollo at the hour of death:

When I seemed to be turning to a tree with trunk and branches

Growing indurate, turning to stone, yet burgeoning

In Laurel leaves, in hosts of lambent laurel,

Quivering, fluttering, shrinking, fighting the numbness

Creeping into their veins from the dying trunk and branches!

“Continually our eyes are opened wider, the depth of our vision is increased,” wrote the astronomer Harlow Shapley. It was a remark that deeply moved the photographer in later life, as his “voyage of discovery” turned inward. The details, nuances, and experiences of his immediate surroundings, or, as he put it, “the world on my doorstep,” inspired Strand’s compelling photographic explorations at the end of his fife. In these final images of his Orgeval garden, three of which open this issue, Paul Strand was able to fulfill—in what appear to be the simplest and most concise forms—the challenge he faced in all his work: to evoke the everlasting.

THE EDITORS

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Editor's Note

-

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteEditors' Note

Summer 2000 -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteElements Of Style

Fall 2017 -

Editor's Note

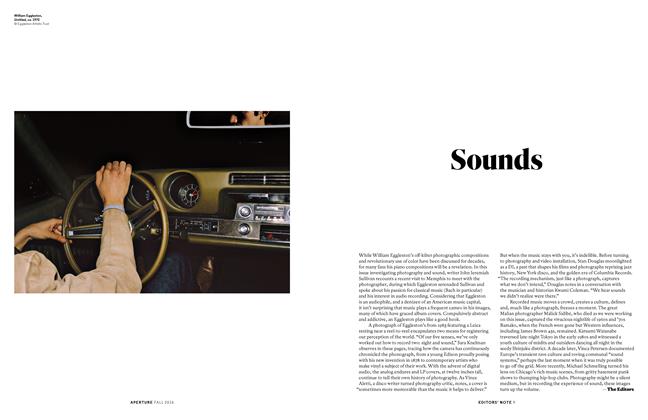

Editor's NoteSounds

Fall 2016 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteNew York

Spring 2021 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

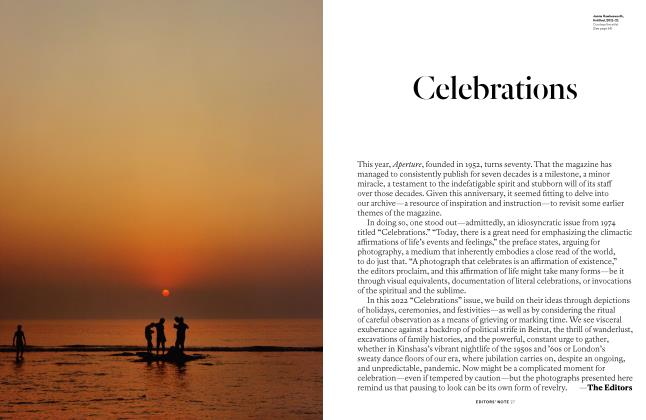

Editor's NoteCelebrations

SPRING 2022 By The Editors -

Editor's Note

Editor's NoteWe Make Pictures In Order To Live

SPRING 2023 By The Editors