The Mask of Opticality

Enno Kaufhold

Exploiting the camera’s ability to provide optically precise and apparently neutral records, an influential group of German artists are reworking such familiar genres as portraits, landscapes, and architectural photography.

Pictures do not explain themselves, and even if two are identical in form, it does not mean that they share the same intentions or content. Photographs are not excluded from this; those made with the greatest possible optical precision may have completely different contents or—since photographic technology can be used to produce pictures virtually automatically— may have no intended contents at all. Thus it is not always easy to distinguish between photographs that record in a purely mechanical manner and those that, guided by the human intellect, use photographic precision to show essential things. Hence, if something appears hidden behind the photographic mask of opticality, you can look into its true face only if you pull off this mask and peer behind it.

This is not a phenomenon peculiar to photography, but something philosophers have reflected upon for over two thousand years: the difference between what something appears to be, and what it actually is. For centuries, painters have discriminated between appearance and essence, and, to an extent, have attempted to paint essence in its appearance. With the invention of photography, technology for the first time made things appear without any apparent activity by intellect or handicraft. It is hardly surprising then that the most photographic of all photographs—optically precise, accurately detailed images—have been the ones most emphatically denied the claim to reproduce essence. Despite this, there has long been a tradition of “photographic” photography, with outstanding photographers in every country working in this style.

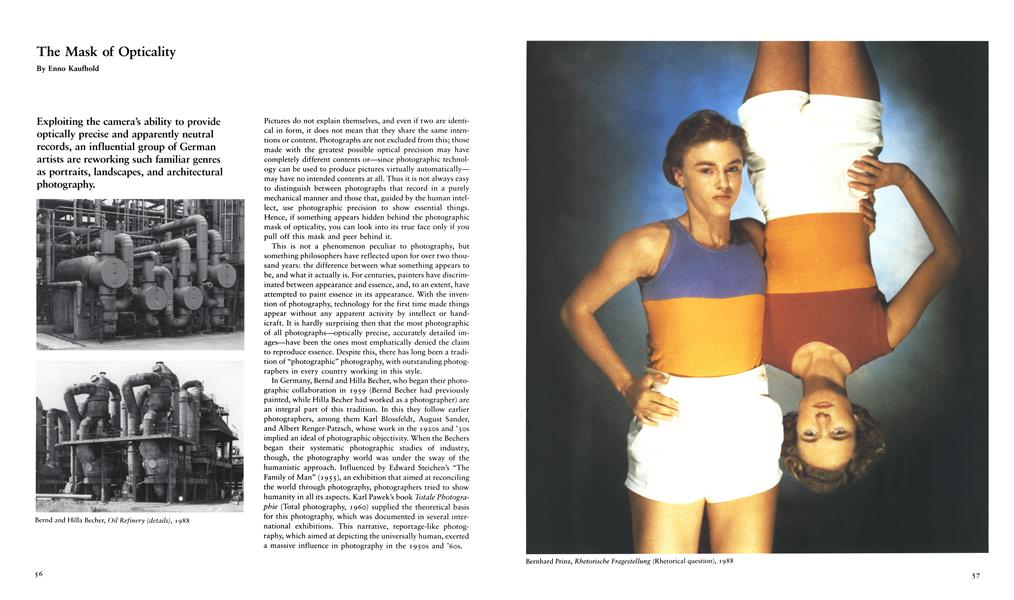

In Germany, Bernd and Hilla Becher, who began their photographic collaboration in 1959 (Bernd Becher had previously painted, while Hilla Becher had worked as a photographer) are an integral part of this tradition. In this they follow earlier photographers, among them Karl Blossfeldt, August Sander, and Albert Renger-Patzsch, whose work in the 1920s and ’30s implied an ideal of photographic objectivity. When the Bechers began their systematic photographic studies of industry, though, the photography world was under the sway of the humanistic approach. Influenced by Edward Steichen’s “The Family of Man” (1955), an exhibition that aimed at reconciling the world through photography, photographers tried to show humanity in all its aspects. Karl Pawek’s book Totale Photographie (Total photography, i960) supplied the theoretical basis for this photography, which was documented in several international exhibitions. This narrative, reportage-like photography, which aimed at depicting the universally human, exerted a massive influence in photography in the 1950s and ’6os.

By comparison, the Bechers, with their deserted and objectoriented industrial views, were working in out-of-the-way aesthetic territory. Nevertheless, over the years they continued to photograph all sorts of industrial structures: water towers, grain silos, gas containers, limekilns, pithead gears, blast furnaces, steel mills, coal bunkers, cooling towers, processing plants, and half-timbered houses. To find their subjects, the Bechers toured West Germany, Holland, France, Belgium, England, and the United States. Not only the photographic precision with which they depicted these scenes, but also the systematic and methodical nature of their project, corresponded to the new seeing that achieved prominence in the 1920s. Both Blossfeldt and Sander, for example, had already produced photographic series of plants or people.

Although nobody is actually working in any of the Bechers’ photographs, their pictures nevertheless imply the presence of the laboring person. For human beings not only invaded nature through work, pushing it back with their industrial facilities; in a sense they also created themselves, through a dialectical process. Just as one can reconstruct the whole texture of a civilization from every stone in an ancient ruin, one can also reconstruct the life of modern society from the Bechers’ views of industrial structures. And since many of these industrial facilities and objects no longer exist, it is from their photographs that future generations (for whom industrial archeology will be more than just a trendy term) will derive the dialectical process that has produced modern industrial society.

The distinctive form of the Bechers’ photographs is due in part to the uniform lighting and systematic composition of each picture. The diffuse, almost unfocussed illumination, which rejects highlights and chiaroscuro effects, gives these photographs a consistent visual appearance, and gives each picture its magic charm. The overall form of the work also includes the conceptual factor of the series, the resolute line-up of pictures of similar kinds of industrial objects, seen always from the same point of view, and the typology of these objects that results. This is still evident today, when the Bechers have begun to present their prints in larger formats and to exhibit them individually, not just in groups.

The Bechers’ systematic labor, which has been going on for almost three decades now, is unprecedented for both German and international photography. It has even spawned a school— in a very literal sense, since Bernd Becher has taught for many years at Düsseldorfs Kunstakademie, and several of his students, including Axel Hütte, Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, and Thomas Ruff, have made names for themselves internationally. However, it would be wrong to assume that these disciples are following directly in the path set out by their mentor. Not only is there a generation’s difference in age (all these students were born during the 1950s), there has also been a change of paradigm in their work, from pure photography to a self-conscious form of work which, sloughing off the rules of traditional photography, aims unmistakably at achieving the status of art.

Our intention is not to make aesthetically pleasing photographs but to make detailed illustrations which, because of the lack of photographic effects, become relatively objective.

We do not intend to make reliquaries out of old industrial buildings. What we would like is to produce a more or less perfect chain of different forms and shapes. . . .

BERND AND HILLA BECHER, Kunst-Zeitung (Düsseldorf), 1969

The element that all the work shares is photographic precision; however, the intentions behind it vary. Each of Becher’s pupils has chosen his or her own special precinct and found a distinct pictorial stamp; yet none of them resorts to the same absolute exclusivity and systematization as their teacher. Furthermore, the context they work in has changed. After the integration of photography into the international art market during the 1970s and especially the ’8os, the Bechers’ disciples managed to establish themselves in the art world very quickly. (The Bechers, of course, had made a name for themselves in the art world decades ago.)

Thus, Axel Hütte initially photographed the dreary, deserted staircases, basement apartments, and garage entrances of standardized postwar German architecture. Based on a central perspective and eschewing all special effects, his seemingly quiet views offered images of terror rather than harmony. Menace lurked behind every corbeling, every door. During the 1980s, though, Hütte, like many of his colleagues, switched to color photography. He did so both for aesthetic reasons and because of improved laboratory conditions. Moreover, new and more durable color paper made it possible to produce larger prints. Hütte’s newer pieces have been made in Italy. Architecture is still part of the picture—not as the only subject, but as an element interlaced with nature. In Hütte’s recent work the connections between historic walls and organic nature become visible.

As far back as 1979, Thomas Struth—no doubt with a glance toward his mentor—advocated “photographs without any personal signature.” Like Hütte, he too launched into black-and-white architectural views. But although architecture dominated these pieces, Struth was interested neither in architectural photography in a conventional sense nor in the architect’s style. Struth’s goal was to depict the material side of contemporary urban reality with its different, disparate signs. In his pictures public space is presented as a modern jungle. In the course of the 1980s Struth took photographs in the most diverse big cities and suburbs. Whether in black and white or color, these photographs are distinguished by their optical precision and emphatically central perspective. Entitled “Unbewusste Orte” (Unconscious places), these pictures have been widely exhibited and published. Over the past few years, Struth has also made a series of portraits of families, which likewise aim at optical precision. Each family poses with extremely earnest faces, the members placed at the same distance from the camera (and from the photographer). In contrast to the city images, these group portraits have no spatial depth, a lack that underscores their serious and statuary character.

While for Hütte and Struth, as for the Bechers, human beings remain invisible or are only indirectly suggested in the pictures, Andreas Gursky includes human beings in his pictures of architecture and landscapes. But these figures are not a form of decor in the traditional sense; only marginal in the overall picture, they melt into the natural surroundings. In Gursky’s series “Sonntagsbilder” (Sunday pictures) and other works, people are shown fishing, swimming, pursuing leisure activities. Yet their behavior is so restrained that it appears neither genrelike nor anecdotal. This reduction of activity is matched by the diffuse lighting, which, as in the Bechers’ oeuvre, never varies.

Using the same lack of lighting effects and zooming in on individual faces with the blank stare of the camera, Thomas Ruff’s portraits reveal the impact of the Bechers’ work. For the past several years Ruff has photographed these portraits in a systematic way; as with the work of the Bechers, Ruff’s portraits reveal a strong conceptual aspect. By no means can Ruff be considered a portraitist in the conventional sense. His sitters wear no makeup, so that their every facial blemish and dermatological flaw is clearly revealed; moreover, the mise-enscène is starkly simple. The models are frontally lit, so that his pictures resemble ID-card pictures or photobooth images. Adding to the fascination of these portraits is the fact that Ruff presents them in huge blowups—up to ten feet tall—producing a stunning visual effect.

Given the deadpan, seemingly styleless nature of his pictures, it comes as no surprise that Ruff is put down as a bungler by some German photographers, concerned more with craft than with images; these photographers also rail against the fact that his pictures are sold as art, fetching high prices in the bargain. As a result, Ruff has been personally vilified and the art market per se has been defamed. This too is evidence, although circumstantial, of the gap between the work of the Becher disciples and pure photography.

An even clearer connection with art can be seen in the photographs of Günther Förg, whose work with the camera constitutes only one aspect of his artistic practice, since he also paints and sculpts. In his multimedia work Förg presents his photographs both as parts of an ensemble, in site-specific installations, and as autonomous entities. Förg’s images dealing with death are highly original, especially when he focuses on his own death—for example, in a photograph of himself lying shattered at the foot of a stairway. His window pictures, which he makes in buildings that are famous examples of Modernist architecture, treat not only the interior design but also the external surroundings. Here, the clarity, sternness, and precision with which Förg depicts these buildings reflects the harmony and proportion of the structures themselves. Blown up to the size of windows, these photographs, with their enlarged grain, develop their own coloristic lives, reflecting Förg’s painterly side.

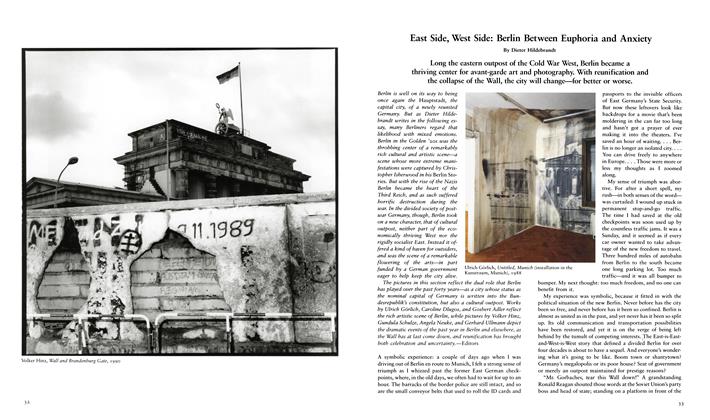

The fact that optical precision can be used to serve a variety of goals is further underscored by Bernhard Prinz’s photographic oeuvre. Starting with architecture, Prinz initially exhibited furniturelike objects into which he integrated his photographs. Next came still lifes set up specifically for the camera, pieced together out of the most diverse domestic items—silverware, vases, knickknacks—which he garnished with luxurious textiles, creating lush images recalling the rich attention to objects found in advertising product shots.

In his latest works, Prinz has turned to the portrait, and especially the allegorical portrait, arranging his sitters in simple yet dramatic poses of a sort found in photo-studio shots from an earlier era. Only the oversized prints and the elaborate wooden frames—which Prinz constructs himself—make the resulting works different from their thematic counterparts in studio photography. Portrait photography as a craft is thereby raised to the level of art. As in advertising, the objects and the portraits offer a seductive image, but here the photographs are meant only to refer to advertising, to suggest through this irritation new dimensions of interpretation.

Prinz’s work quotes former photographic styles only ironically. In this his photographs are comparable with those of Ruff and, to a lesser extent, Gursky and Struth. If Prinz’s portraits look like pictorial studio portraits from the beginning of the twentieth century, or his staged photographs like advertising pictures from the 1920s and ’30s, they do so allegorically. Prinz—like many other artists today—uses historical images in a process of art recycling.

Cinema and especially TV have taken over the task of recording reality from photography. In the coldly calculated pictures of Struth, Gursky, and Ruff, as well as in the staged pictures of Förg and Prinz, reality appears again, in an elevated, aesthetic form. The balanced and contemplative images of these artists display an Apollonian spirit. Behind their mask of opticality we find competing impulses toward tradition, modernism, and timelessness. In these works photography regains what it has lost through overuse: its aura. □

Joachim Neugroschel

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Metaphysicians Of Dionysus: Comments On The New German Photoworks

Spring 1991 By Wilfried Wiegand -

Another German Autumn

Spring 1991 By Ulf Erdmann Ziegler -

East Side, West Side: Berlin Between Euphoria And Anxiety

Spring 1991 By Dieter Hildebrandt -

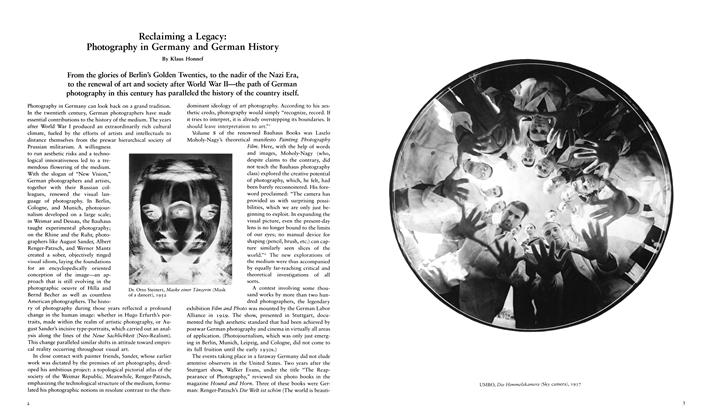

Reclaiming A Legacy: Photography In Germany And German History

Spring 1991 By Klaus Honnef -

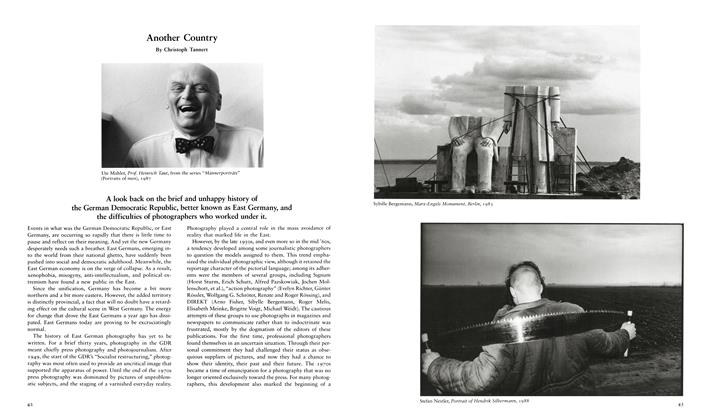

Another Country

Spring 1991 By Christoph Tannert -

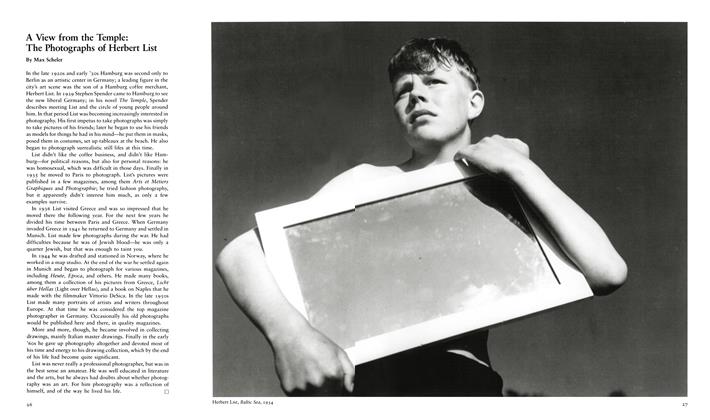

A View From The Temple: The Photographs Of Herbert List

Spring 1991 By Max Scheler