East Side, West Side: Berlin Between Euphoria and Anxiety

Dieter Hildebrandt

Long the eastern outpost of the Cold War West, Berlin became a thriving center for avant-garde art and photography. With reunification and the collapse of the Wall, the city will change—for better or worse.

Berlin is well on its way to being once again the Hauptstadt, the capital city, of a newly reunited Germany. But as Dieter Hildebrandt writes in the following essay, many Berliners regard that likelihood with mixed emotions. Berlin in the Golden ’20s was the throbbing center of a remarkably rich cultural and artistic scene—a scene whose more extreme manifestations were captured by Christopher Isherwood in his Berlin Stories. But with the rise of the Nazis Berlin became the heart of the Third Reich, and as such suffered horrific destruction during the war. In the divided society of postwar Germany, though, Berlin took on a new character, that of cultural outpost, neither part of the economically thriving West nor the rigidly socialist East. Instead it offered a kind of haven for outsiders, and was the scene of a remarkable flowering of the arts—in part funded by a German government eager to help keep the city alive.

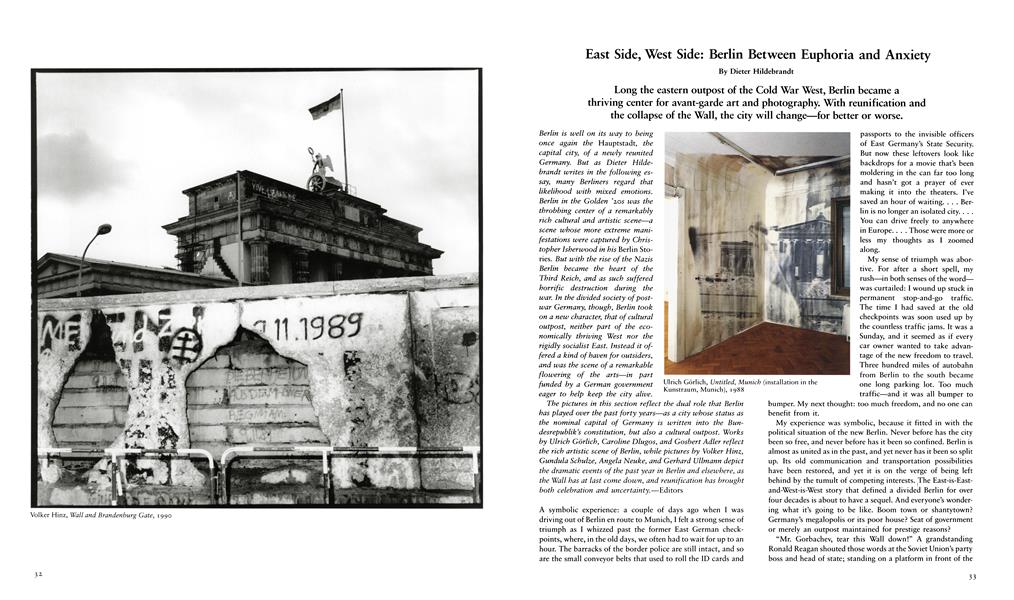

The pictures in this section reflect the dual role that Berlin has played over the past forty years—as a city whose status as the nominal capital of Germany is written into the Bundesrepublik’s constitution, but also a cultural outpost. Works by Ulrich Gör lieh, Caroline D lugos, and Gosbert Adler reflect the rich artistic scene of Berlin, while pictures by Volker Hinz, Gundula Schulze, Angela Neuke, and Gerhard Ullmann depict the dramatic events of the past year in Berlin and elsewhere, as the Wall has at last come down, and reunification has brought both celebration and uncertainty.—Editors

A symbolic experience: a couple of days ago when I was driving out of Berlin en route to Munich, I felt a strong sense of triumph as I whizzed past the former East German checkpoints, where, in the old days, we often had to wait for up to an hour. The barracks of the border police are still intact, and so are the small conveyor belts that used to roll the ID cards and passports to the invisible officers of East Germany’s State Security. But now these leftovers look like backdrops for a movie that’s been moldering in the can far too long and hasn’t got a prayer of ever making it into the theaters. I’ve saved an hour of waiting. . . . Berlin is no longer an isolated city. . . . You can drive freely to anywhere in Europe. . . . Those were more or less my thoughts as I zoomed along.

My sense of triumph was abortive. For after a short spell, my rush—in both senses of the word— was curtailed: I wound up stuck in permanent stop-and-go traffic. The time I had saved at the old checkpoints was soon used up by the countless traffic jams. It was a Sunday, and it seemed as if every car owner wanted to take advantage of the new freedom to travel. Three hundred miles of autobahn from Berlin to the south became one long parking lot. Too much traffic—and it was all bumper to bumper. My next thought: too much freedom, and no one can benefit from it.

My experience was symbolic, because it fitted in with the political situation of the new Berlin. Never before has the city been so free, and never before has it been so confined. Berlin is almost as united as in the past, and yet never has it been so split up. Its old communication and transportation possibilities have been restored, and yet it is on the verge of being left behind by the tumult of competing interests. The East-is-Eastand-West-is-West story that defined a divided Berlin for over four decades is about to have a sequel. And everyone’s wondering what it’s going to be like. Boom town or shantytown? Germany’s megalopolis or its poor house? Seat of government or merely an outpost maintained for prestige reasons?

“Mr. Gorbachev, tear this Wall down!” A grandstanding Ronald Reagan shouted those words at the Soviet Union’s party boss and head of state; standing on a platform in front of the Brandenburg Gate, the American president was speaking to the Berliners, to the entire world, and to his own electorate. The occasion was a city jubilee: Berlin was 750 years old. Two years later the unbelievable happened: Gorbachev contributed decisively to the collapse of the Wall. His visit to Berlin in early October 1989, his outspokenness among the East Berlin party princes, his ironic glances and laconic one-liners, shook the East German regime so thoroughly that the Wall opened up almost spontaneously on November 9, 1989.

By then, however, the Wall was something other than a mere barricade. Its western side had become the longest strip of graffiti in the world, a running fence of the imagination, a panoramic vision for artists and dilettantes. And an endless attraction for photographers from all over the world. The comic muse had also gotten hold of the monstrous and anachronistic concrete wall. This wasn’t the Wall, this was the Rostock autobahn hung out to dry. That was one of the many jokes that Berlin’s popular humor had come up with.

Meanwhile, the Wall has crumbled. Twelve percent of all Germans have taken home a scrap or a shred of this, the most modern of all antiques. However, the more interesting pieces are now to be found in the salons and castles of the wealthy, in exclusive galleries and avant-garde museums. You can find the Wall in Ronald Reagan’s home and in the Vatican garden, in the house of a businessman in Phoenix, Arizona, and at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, where Churchill supposedly coined the term “Iron Curtain.”

The worldwide interest in the “anti-Fascistic protection wall” is so vast that Berlin should have long since begun fencing off a couple of feet of the Wall in situ, to save it from total destruction and to preserve it as a historic document, a historical formation—like ancient Roman city walls or Greek temple streets or Minoan palaces: a forum berolinum coming from a brief, bad past and heading toward a future that is even more uncertain, although more suspenseful, than may be apparent amid the reunification euphoria. Now more than ever, people in both reunited parts are asking: What’s to become of us?

These questions can also be read in people’s faces. The status quo, you see, was a cemented balance, in which each half had its special function: West Berlin as the showcase of the West, an island of freedom, a demonstration of the democratic way of life, an outpost of the Free World, a PR agency of parliamentarianism; East Berlin as the capital of the German Democratic Republic, the parade ground of bureaucratic socialism, the demo model of the central planning system, the parlor in the crumbling house of the GDR. For decades, both parts of the city had been exhibition models of their respective systems, and they seemed downright'predestined for the job. Berlin already had not only two railroad junctions, Ostkreuz and Westkreuz, but also two central areas since the 1920s: a historic old Prussian one in the eastern portion and a modern, elegant, efficient one along the axis of the Kurfürstendamm in the western portion.

However, the dramatic—and photogenic—aspect of the current situation is as follows. Not only has the Wall come tumbling down, but so have the strutting and blustering of confrontation, the duel of two global systems, the showdown of two ideologies. The Berliners—even if they wanted to be—are no longer representatives or prototypes of the eastern and the western worlds. They now wander through the old vast areas of their city, going astray, getting stuck (not only in traffic), or experiencing the adventures of a new dimension.

A quick backward glance at the recent history of the city may help to clear up a few questions and anxieties. For Berlin has always been a city of paradoxes, seeming incompatibilities, and nonstop conflicts. January 1991 marked an anniversary: 120 years earlier, the Prussian residence had promoted Berlin to the capital of Germany. The Prussian king became emperor of a Germany that he didn’t like (because it watered down the elitist notion of Prussia) and that didn’t like him (because it was scared of his chancellor, Bismarck). And in this imperial Berlin, there was a yawning gap between two worlds. The gigantic construction boom of the “Gründerzeit,” the period of rapid industrial expansion, 1871—73, contrasted with the indescribable poverty of Berlin’s proletariat. Wilhelm IPs military parades were attacked in Gerhart Hauptmann’s critical plays, and the colossal historical canvasses in the official museums were contravened by, say, Edvard Munch’s avant-garde The Scream, 1893. One year before the outbreak of World War I, a man who was intimate with the city wrote: “Berlin is doomed to keep becoming and never to be.” Berlin, at that time, was already a tension-fraught work in progress.

The contrasts intensified after World War I. For one thing, Berlin could previously be taken in at a glance; now it turned into a megalopolis: in 1920 its suburbs—eight smaller towns and some sixty hamlets—became part of the city. This administrative act resulted in a Berlin of four million people. And the Golden ’20s were launched: a time of cabarets and naked reviews, when intellectual highlife replaced military arrogance, glamour superseded glory. But that “golden” decade was also the period of massive inflation, the period of dreadful economic misery and epidemic unemployment. Strikes, putsches, political assassinations, and police brutality were the order of the day, while the evening brought the biggest entertainment that Berlin had ever witnessed. And then the Nazis broke into this conflict-ridden situation—at first not much more than a political AÍ Capone gang kicking up a rumpus.

In 1927, Berlin was still laughing at the strange nationalist neurotics. But six years later the Nazis usurped power, and the critical spirit of the city was broken. Germany’s leading intellectuals were driven out or locked up or silenced. Most of the works devoured in the great book burning of May 10, Í933, were by authors who had lived and written in Berlin. The Golden ’20s yielded to the brown ’30s and then the bloody ’40s.

The year 1945 brought a new beginning—but in a city that no longer existed. Berlin was a pile of ruins, at best a utopia. And even the ruins were divided, and the utopia split into two versions, East and West. Berlin became the urban setting of the Cold War. But the survivors had more important things to think about: food, heat, shelter. Any trees that the bombs had spared in the renowned Tiergarten park were chopped down by the Berliners during the icy winters. Yet the city was filled with a unique euphoria: plays were mounted everywhere. All of Berlin was a stage—to freely paraphrase Shakespeare.

Then all at once, Stalinism struck with the Berlin Blockade, the West responded with the airlift, and then came the drama that can be summed up in a permanent headline: The Berlin Crisis. On August 13, 1961, the Wall definitively separated the two parts of the city, but not—one could state somewhat grandiloquently—the hearts of the Berliners. Berlin was considered a down-to-earth city, but it had a certain flair for the melodramatic. That was why President Kennedy’s statement, “Ich bin ein Berliner,” could cause such a sensation. In the difficult days of 1963, those words were a spiritual lifesaver for the people of Berlin.

And now? A grand future or a petty one? A bombastic future or a lamentable one? Will big business take over the city or will it be crushed by the thousand problems of the former GDR? Or both? Will the gap between East and West now turn into a socioeconomic conflict between high and low, old and new, rich and poor? Will the German government come to Berlin or will there be nothing but empty rhetoric? Will the Olympic Games be held here in the year 2000 or will new subsidy programs have to be implemented before then?

It is not the literati, not the playwrights, not the singers who can expose the full gamut of feelings. This is the job of the photographers, whose hour has struck. They are helping to express the vast subjectivity of this city: the fear and resignation, the confidence and elegance, the contradiction and jubilation, which in the days when the Wall was opened could be reduced to a single word: “Madness!” □

Joachim Neugroschel

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Metaphysicians Of Dionysus: Comments On The New German Photoworks

Spring 1991 By Wilfried Wiegand -

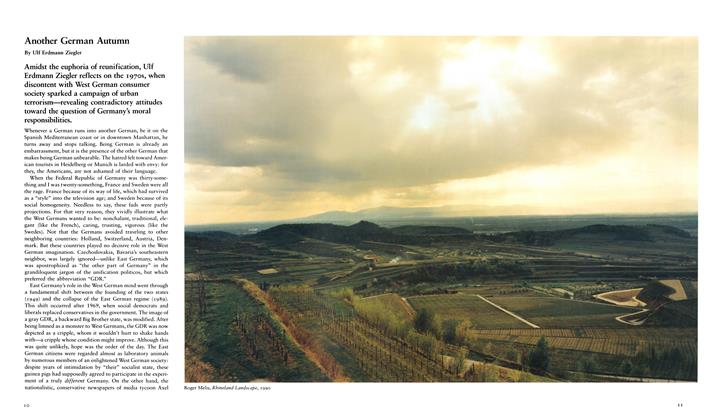

Another German Autumn

Spring 1991 By Ulf Erdmann Ziegler -

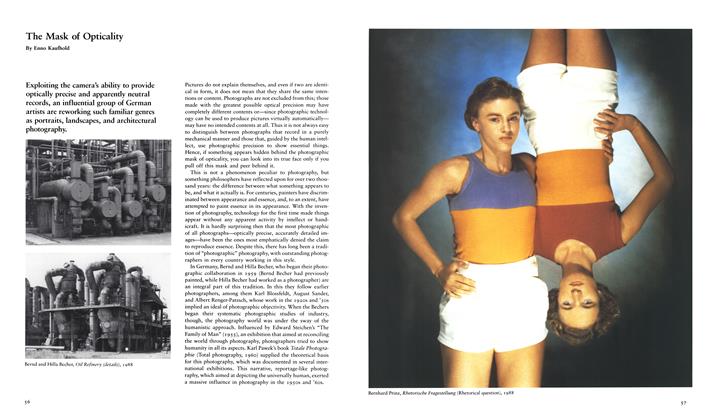

The Mask Of Opticality

Spring 1991 By Enno Kaufhold -

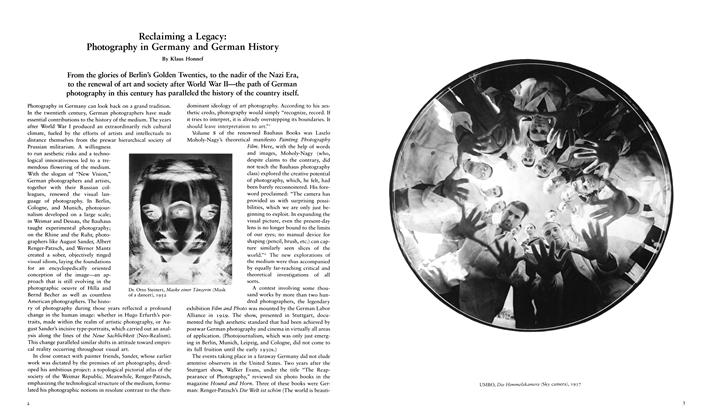

Reclaiming A Legacy: Photography In Germany And German History

Spring 1991 By Klaus Honnef -

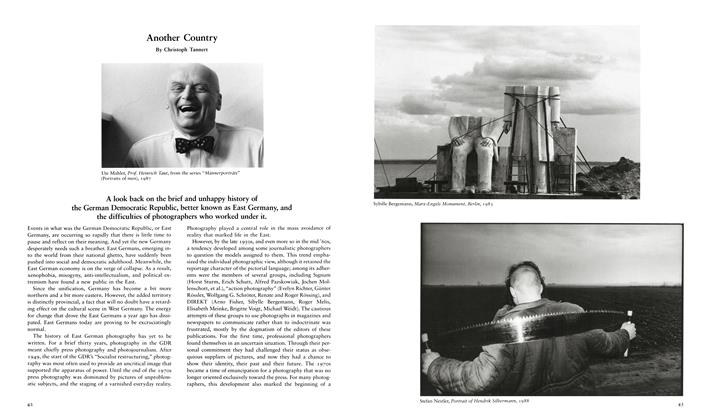

Another Country

Spring 1991 By Christoph Tannert -

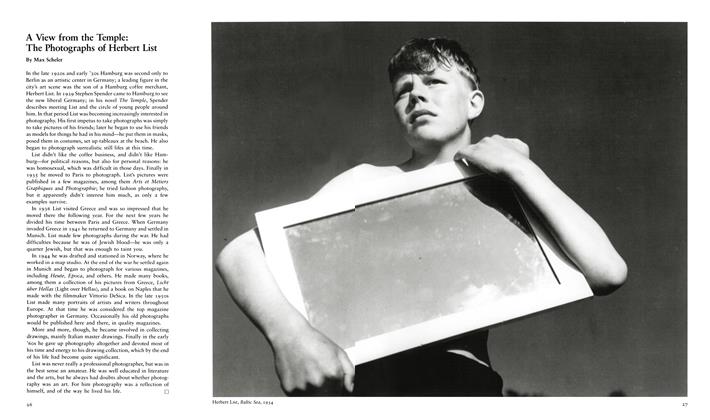

A View From The Temple: The Photographs Of Herbert List

Spring 1991 By Max Scheler