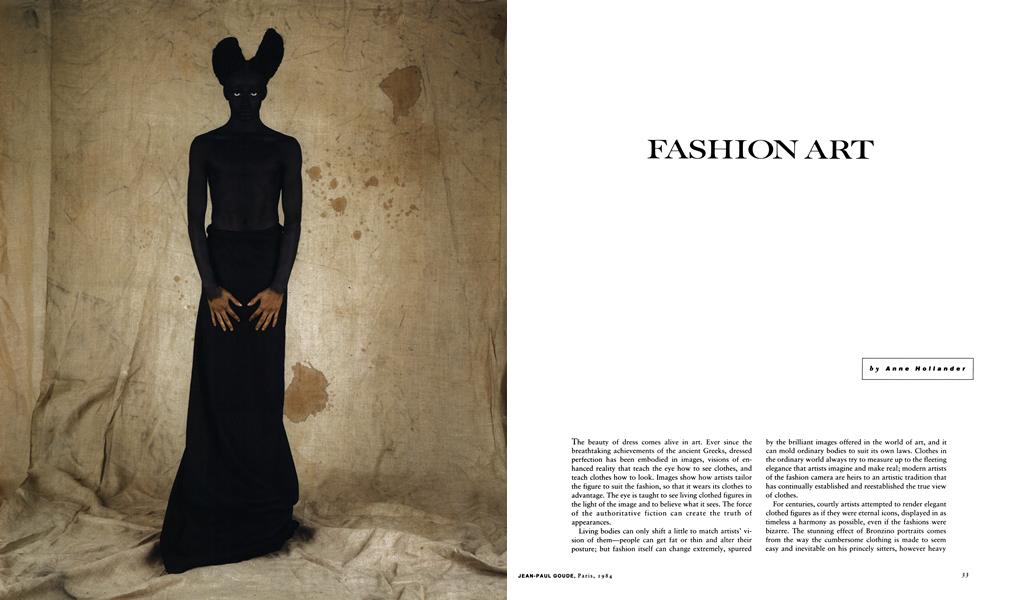

The beauty of dress comes alive in art. Ever since the breathtaking achievements of the ancient Greeks, dressed perfection has been embodied in images, visions of enhanced reality that teach the eye how to see clothes, and teach clothes how to look. Images show how artists tailor the figure to suit the fashion, so that it wears its clothes to advantage. The eye is taught to see living clothed figures in the light of the image and to believe what it sees. The force of the authoritative fiction can create the truth of appearances.

Living bodies can only shift a little to match artists’ vision of them—people can get fat or thin and alter their posture; but fashion itself can change extremely, spurred by the brilliant images offered in the world of art, and it can mold ordinary bodies to suit its own laws. Clothes in the ordinary world always try to measure up to the fleeting elegance that artists imagine and make real; modern artists of the fashion camera are heirs to an artistic tradition that has continually established and reestablished the true view of clothes.

For centuries, courtly artists attempted to render elegant clothed figures as if they were eternal icons, displayed in as timeless a harmony as possible, even if the fashions were bizarre. The stunning effect of Bronzino portraits comes from the way the cumbersome clothing is made to seem easy and inevitable on his princely sitters, however heavy and taxing it really may have been, and hard to keep in proper trim. Although clothes were actually made by tailors, fashion in the sixteenth century was inspired and moved along by such artists as Titian and Bronzino, who could turn all absurdities and grotesqueries into graceful adornments, and even produce a longing for more of them.

In the superior world of the painter, noble personages in all sorts of awkward gear were created and presented in a state of ideal dignity and refinement; and so a standard was set for perfect appearance that might be followed by the living originals, who could feel beautified by their trappings instead of trapped. Consequently, still bigger lace ruffs and even thicker silk skirts might continue in vogue, even into the next generation, because Rubens and Van Dyck and their colleagues were at work rendering them glorious to see, wonderfully becoming, and apparently effortless to wear.

In the days of ducal courts, empires, and absolute monarchies, the aim of such images was the suggestion of a certain false permanence. The desired effect was of continuity with all past and future greatness, so that fashionable figures in art tended toward substance and stasis, and painterly realism had a sumptuous quality, laden with all the riches of tradition just as the actual clothes were laden with padding, starch, and metallic embroideries. Later styles of painting followed later ideals of elegant living, with their different ways of seeing the beauty of fashion; and fashion changed to suit.

Rococo notions demanded a sense of wit and delicacy in dress, even though the shape and construction of clothes did not change very much; so painters freshened up the palette of elegance and made all clothing seem light as air. Fashion required frothy accessories and mobile postures, all ideally offered in the compelling imagery of Boucher and Watteau, where billowing flesh and fabric seem made of the same lovely stuff, a cloud of erotic allusion spiced with faint irony. The burden of greatness was lifted from chic; people could relax and lean back, or sit on the grass and flirt.

In the 1770s, the inauguration of fashion plates caused a significant new accord between art and clothes. Elegant paintings were no longer the only vehicles for the image of dressed perfection. For the first time, printed pictures of ideal figures sporting modish clothes with supreme flair were published in magazines wholly devoted to the mode. The fashionable world, moreover, had outgrown the confines of court life; it was living in cities, and mixing with interesting strangers. The new fashion art suggested the impersonal flow of urban visual life, and helped replace the fixed stars created by courtly painters of the past. Fashionable dress now had to capture the idle, scanning gaze of the general public, to seek appreciation even on the public street. Anyone could play; and fashion plates—outrageous, wondrous, captivating—showed the way to do it.

Fashion plates sustained a high level of taste and an affinity with the best art of the eighteenth century; but they declined a great deal during the next one. Nineteenth-century fashion plates developed a separate illustrative style that showed no impulse to keep pace with the evolution of serious art. As a result, fashionable dress itself began to seem more and more like vain folly, steadily losing moral and aesthetic prestige as its components became more elaborate and its image less serious. Fashion was also more exclusively associated with women.

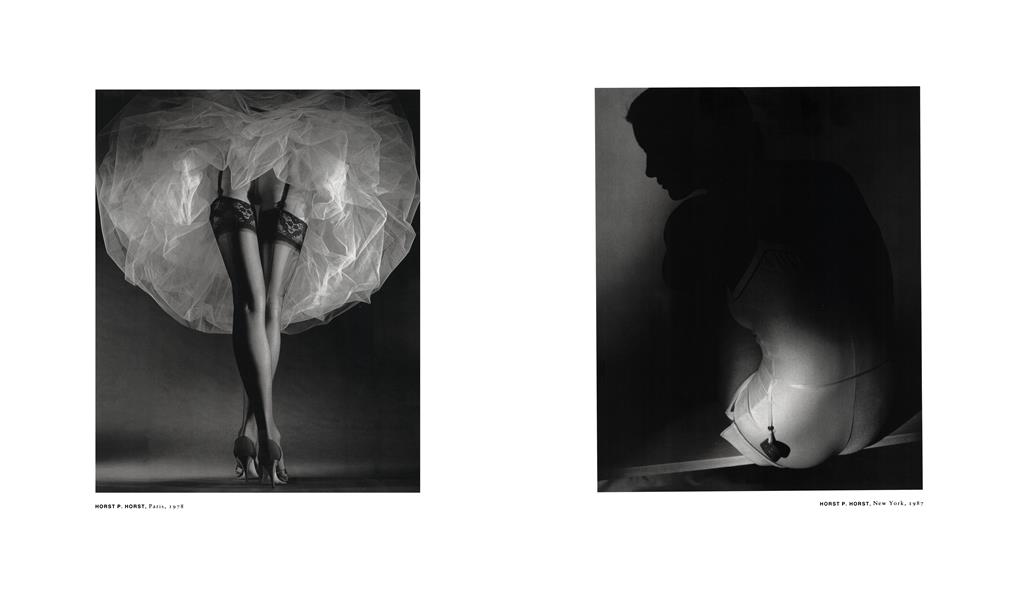

As fashion-plate imagery became more frivolous, suggesting insipidity and moral nullity as it purveyed the effects of puckered taffeta and draped satin, the very details of fashion seemed more spiritually burdensome, more at odds with earnest pursuits and dispositions. Manifold flounces and braid, feathers and veiling, trains and crinolines all took on the ambiguous and limiting flavor of feminine narcissism; and an elegantly clad woman became an unaccountable apparition, delicious to see but obscurely threatening, disconnected from the reasonable arrangements of life.

During all this time, as the nineteenth century progressed, photography was developing in huge creative bursts; but it nevertheless remained retrograde in dealing with the image of female elegance. Until the very end of the century, fashion had no interesting new food for the ravenous camera eye, and dress showed no desire to be created anew by the shaping spirit of the lens. Its own debased illustrative medium held the image of fashion firmly in its genteel paw and stifled the possibility of an imaginative camera life for fashion. Portrait photographs of fashionable personages tended to imitate the effects of old masters instead of exploring explicitly photographic ways to enhance fine clothes.

But painters did better. The glittering visions of the Impressionists added new possibilities to the aura of elegance, new magic to the surfaces of silk dresses and powdered faces, which fashion illustration could never suggest; and they offered a new integration of fashion with the general texture of life, so that the beauty of rich clothes and the beauty of the natural world need not seem at war. This was a prophetic move, one the camera undertook much later.

Modern design and modern art wholly changed the look of fashion for a few short years after the turn of the century. Fashion illustration took a leap forward, inventing an avant-garde style for the image of the clothed figure that linked it to all other objects designed in the new spirit of reduction and abstraction. The increasing prestige of modern architecture and industrial design raised the concept of design itself much higher on the aesthetic scale. Fashion design could once more come into line with fundamental creative endeavor, for the first time in centuries.

Fashionable dress was quickly reduced in scope and increased in clarity; women’s clothing borrowed the essentially abstract shapes of men’s tailoring and began to match the spatial character of male clothing instead of spreading out in waves of fantasy. The graphic art in which fashion was purveyed again bore a relation to the newest developments in modern painting and print making: the body in its dress became a clear-edged, streamlined object made of cubes and cylinders or of flat geometric patterns arranged with dazzling finesse. Fashion art also displayed connections with the imaginative constructions of Braque and Léger, which lent further aesthetic luster to the whole idea of fashion.

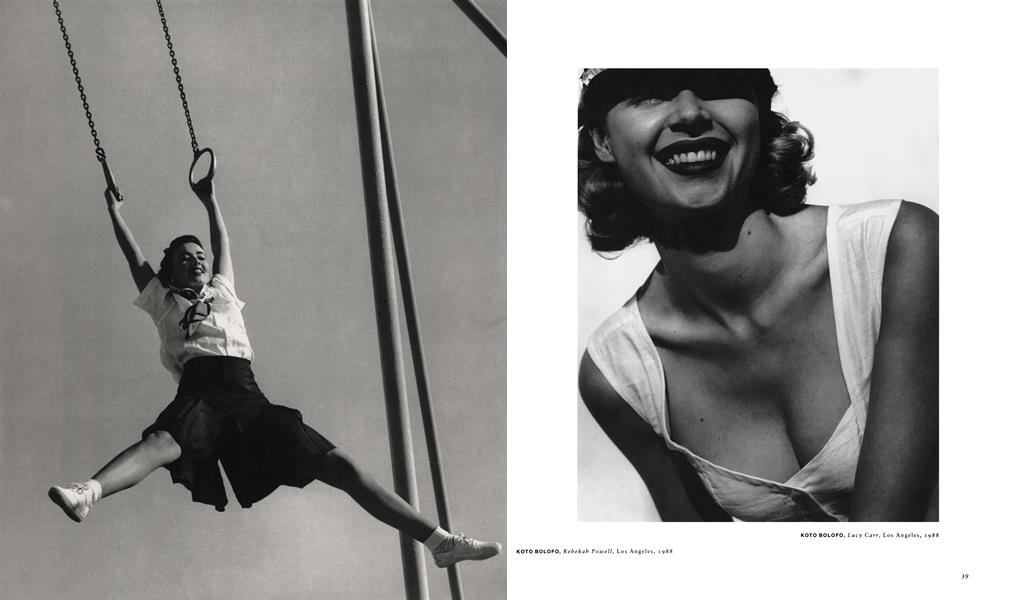

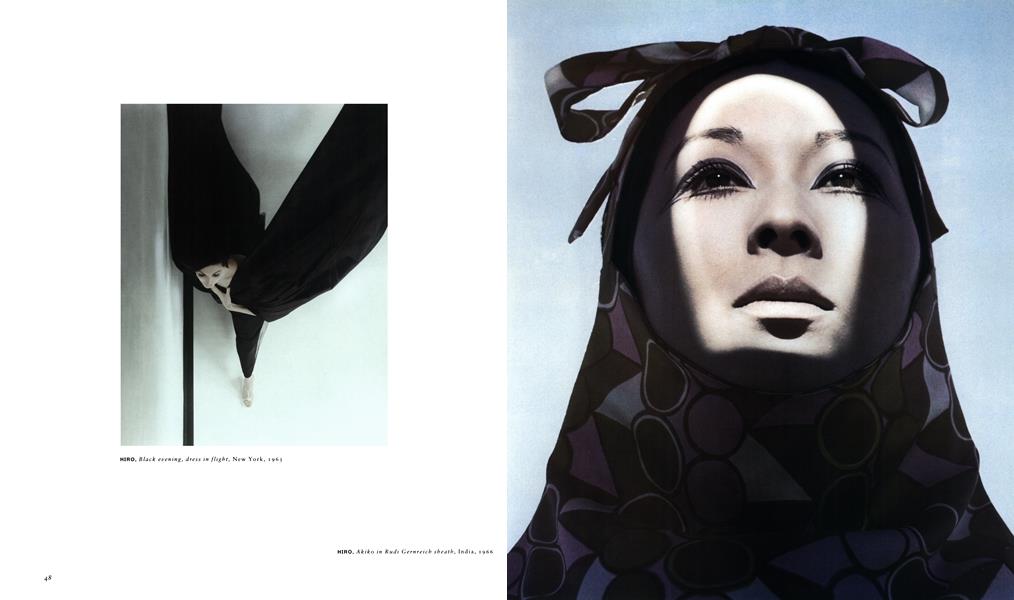

During the first third of this century the camera had been continuously influencing the perception of the new architecture and design, of all man-made things, and of natural phenomena. The vigorous beauty of the modern world was being increasingly celebrated and virtually created by great photographers, whose vision eagerly included the clothed body along with deserts and bridges, cityscapes and rural desolation. Fashion photography, like the prints of the eighteenth century, began its life at the highest level of camera art, which manifested more aesthetic authority and creative power than any other graphic medium of the advancing twentieth century. And so fashion itself was redeemed, not only from the tacky illustrative graphics of the past but even from the impersonal and static world of modern design.

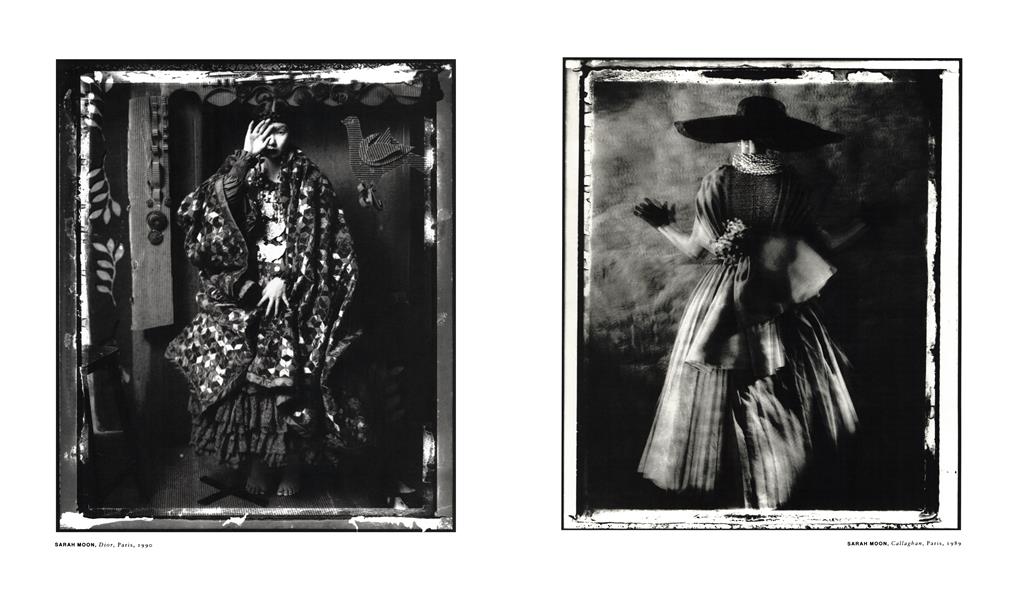

By the 1930s, in harmony with movies and photojournalism, fashion photography began to render the passing chic moment for its own sake, instead of fixing the mode in a timeless image indebted to the old history of painting and engraving or to the new course of the decorative media. This shift of emphasis in fashion imagery had a decisive effect on ideals of dress and irreversibly changed the look of modern clothing. Instead of being designed objects similar to chairs and cars, clothed figures in fashion art began to look like characters in small, unfinished dramas, caught in fantasy moments of acute tension and resonance that had no future and no past. Fashion itself, the very clothes themselves, gradually came to fulfill an ideal not just of free movement through the action of living but of quick replaceability. Mass-produced moments were to be swiftly lived through clad in a shifting sequence of massproduced garments, all ensembles soon giving way to complete new ones, just as they did in the evocative pictures that similarly came and went.

In sharp contrast to past centuries, it became a modern assumption that clothes were not to be remodeled or even radically repaired, only replaced. Although fashion changed constantly in the past, garments still represented the sustained continuity of living. They embodied the phrasing of human life, the tough and flexible endurance of human society itself. When the mode shifted, extant clothes could be picked apart and the precious fabric refashioned so that something new grew out of the destruction of the old. Even when society was actually breaking up and institutions were crumbling, dress with its quasi-organic staying power through fashionable change, with its vital link to its own roots in known materials and handmade structure, spoke to its wearers of survival and stability. Fashion built and rebuilt on its own past.

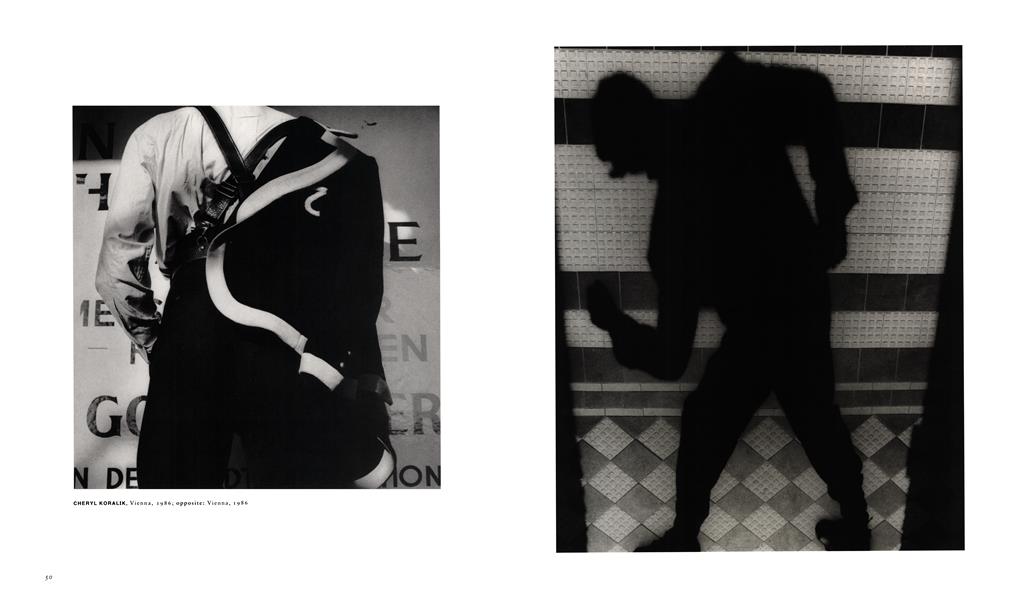

But the modern camera began to suggest the absolute contingency of anything elegant, even something in itself stiff, thick, and still. Since the thirties, fashion photographs have continued to emphasize the dependence of desirable looks on completely ephemeral visual satisfaction, the harmony of the immediate moment only, which exists totally and changes totally. Transition to the next moment occurs by no visible process. Meanwhile the clothes that make people fit into such images are now often made out of inexplicable fabrics and by unseen means, in industrial processes that can also be swiftly adjusted to make whole new sets of garments in great numbers on short notice, each meant to live for a few perfect moments and then be replaced by the next.

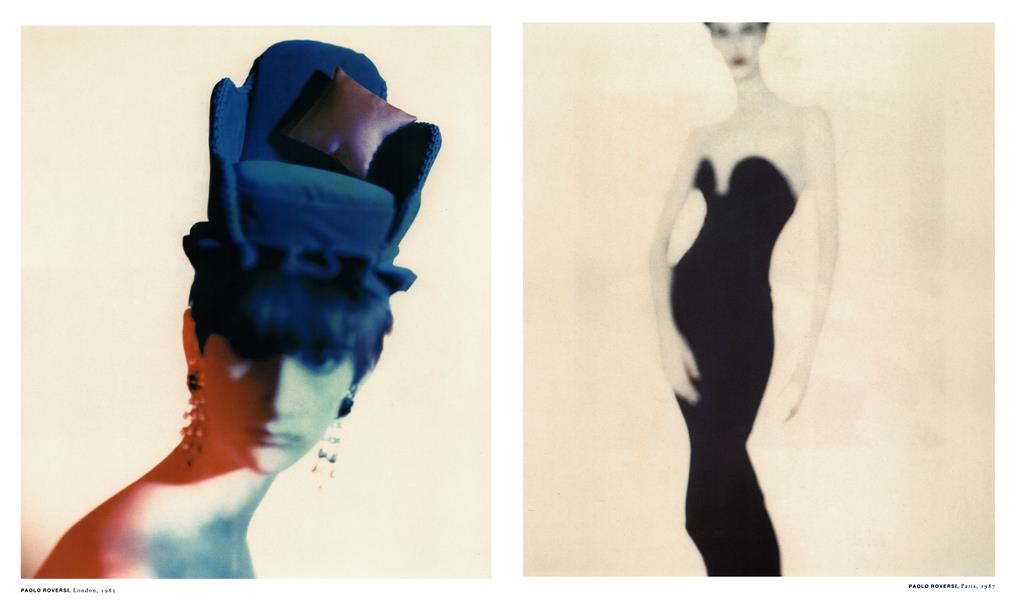

Under the influence of the increasingly suggestive fashion camera, garments ideally look not only quickly disposable but dependent for their current beauty and value on swift changes of psychological ambience. With the camera for its chief medium, fashion has come to seem more and more like a sequence of costumes illustrating a narrative of inward events. The photographic message has been clear that modern men and women may keep visually transforming through clothing with no loss of true personal integrity or consistency, preserving their emotional equilibrium by dressing all the parts they play in the continuing drama of their inner life. The postmodern woman has further learned that disparate, incongruous wardrobe items may not only cohabit in one closet, as if on backstage costume racks, but may now be combined to suit the present-day conflict and ambivalence in most private inward theater. In the new world of freewheeling, overlapping, unrooted camera images, old denim and fresh spangles may be worn not just in quick succession but together.

Practical life is not directly addressed by the fashion camera, any more than it was addressed by Bronzino and Boucher. Women are in fact better able to fit everyday actualities into their closets without direct reference to dream images; those, rather, are for the health of the soul and the nourishment of the inner eye. Women actually build up useful collections of garments in a very clinical spirit, negotiating the marketplace with wary prudence; but the flame of pleasure and fantasy nevertheless glows behind their eyes, lending imaginative force to the enterprise, making it a creative act.

It is the potent imagery of fashion art that provides the glow and generates the true art of dress, feeding the imagination and pushing the visual possibilities of clothing into new emotional territory. Designers need it and work under its influence, relying on the camera to realize what they propose, to ratify its virtues and expound its value, just as the tailors of the Renaissance needed Titian. Today’s fashion is almost entirely perceived and judged through photographs disseminated in the media. Most of the vast audience for fashion sees the work of designers only through the camera’s eye, and responds not directly to fabric and cut but to fabric and cut explained, translated, and ultimately transfigured by varieties of photographic magic. Actual clothes can only follow in the camera’s wake, doing their mundane work of enabling the flow of physical life and sustaining the social world. The deep aesthetic pleasure they can give, the sparks of visual delight they can strike, are always largely in debt to the ideal fictions the lens has created, the vivid images that give fashion its true life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

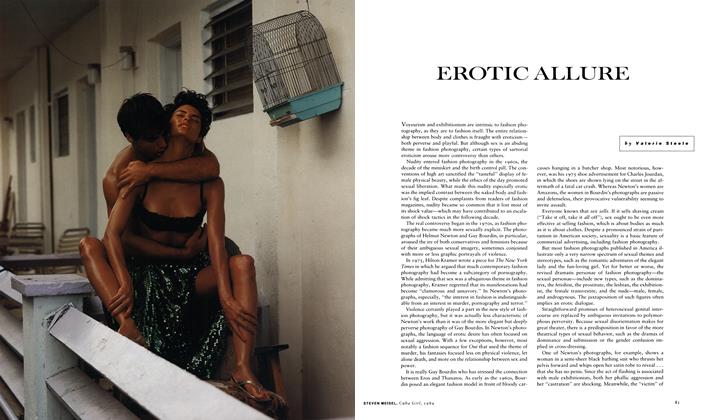

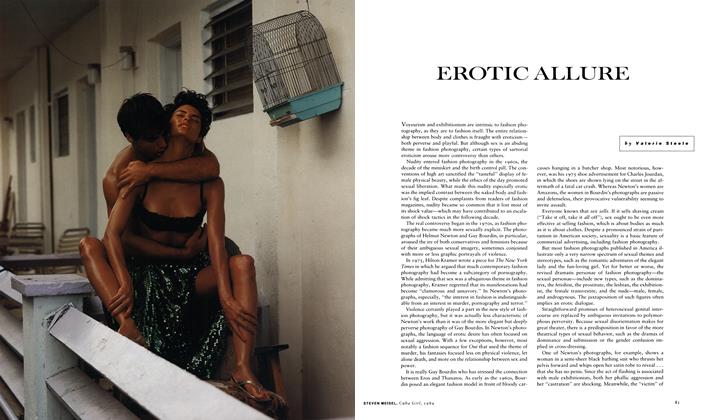

Erotic Allure

Winter 1991 By Valerie Steele -

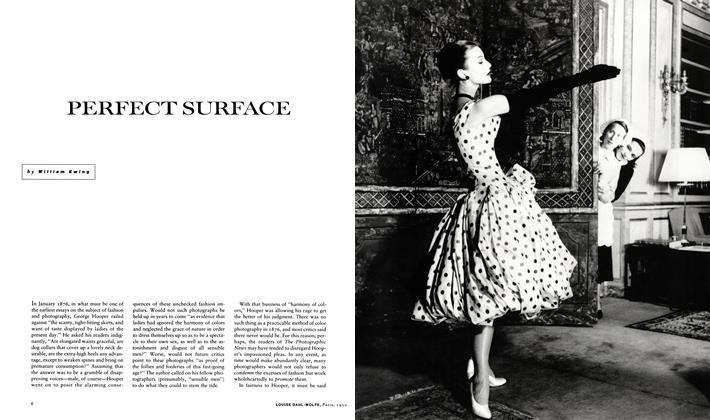

Perfect Surface

Winter 1991 By William Ewing -

Pictures

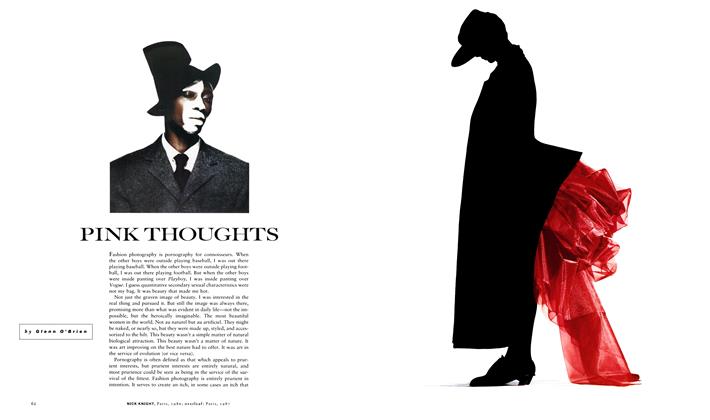

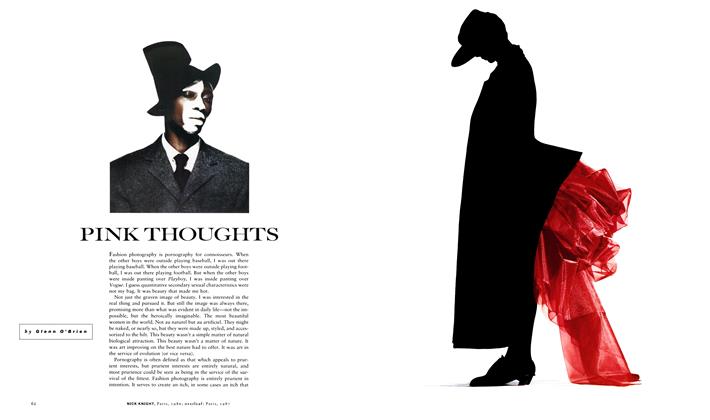

PicturesPink Thoughts

Winter 1991 By Glenn O’Brien -

A Conversation with Karl Lagerfeld

Winter 1991 By Andrew Wilkes -

Blumenfeld

Winter 1991 By Richard Martin -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasVideo Envy

Winter 1991 By Kenneth Miller

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Fashion

-

A Conversation with Karl Lagerfeld

Winter 1991 By Andrew Wilkes -

Words

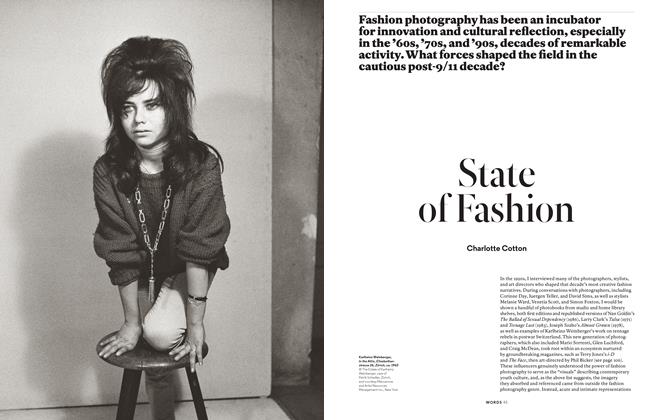

WordsState Of Fashion

Fall 2014 By Charlotte Cotton -

Pictures

PicturesPink Thoughts

Winter 1991 By Glenn O’Brien -

Pictures

PicturesThe Icons

Fall 2014 By Inez & Vinoodh -

Blumenfeld

Winter 1991 By Richard Martin -

Erotic Allure

Winter 1991 By Valerie Steele

Pictures

-

Pictures

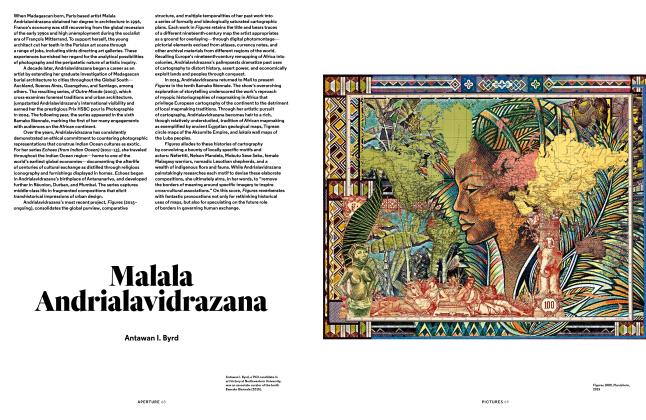

PicturesMalala Andrialavidrazana

Summer 2017 By Antawan I. Byrd -

Pictures

PicturesAshley Walters

Summer 2017 By Candice Jansen -

Pictures

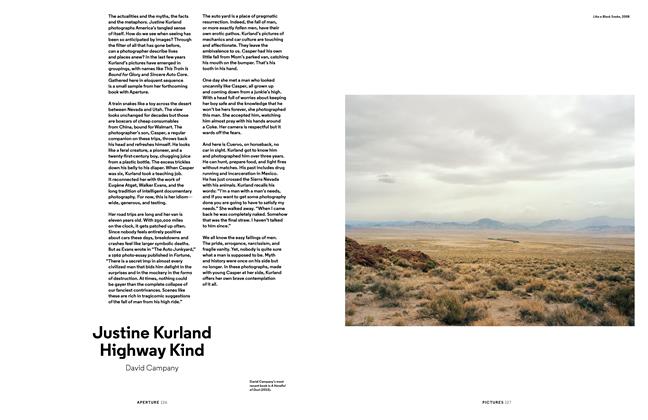

PicturesJustine Kurland Highway Kind

Spring 2016 By David Campany -

Pictures

PicturesRadcliffe Roye

Summer 2016 By Garnette Cadogan -

Pictures

PicturesThe Icons

Fall 2014 By Inez & Vinoodh -

Pictures

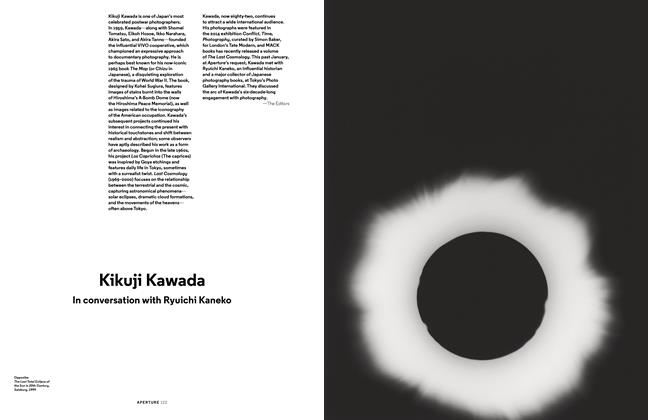

PicturesKikuji Kawada

Summer 2015 By Ryuichi Kaneko