Reclaiming a Cultural Legacy: The Ju/'hoansi of Namibia

ESALEN

Megan Biesele

There are two kinds of bioscope [movies]. One kind shows us as people like other people, who have things to do and plans to make. This kind helps us. The other kind shows us as if we were animals, and plays right into the hands of people who want to take our land.

—Tsamkxao /Oma, /Aotcha, Namibia

The Ju/’hoan Bushmen of Namibia are in transition, not in the old sense of traveling from one water source to another, but in the current exigency of changing their lifestyle in order to survive. They have lost the vast expanse of the Kalahari Desert that enabled them to live, as had the generations before them, from hunting and gathering alone. They have been reduced to the depths of poverty and degradation in rural slums. Now they are struggling to adapt their ancient ways to modern necessity, and to hold onto their remaining land.

Namibians are preparing for profound changes, as seventyfive years of South African colonial domination comes to an end and independence under majority rule begins. The new government’s policies on rural development and ethnic minorities will affect the Ju/’hoansi greatly, but in ways as yet unknown. What the Ju/’hoansi do know, however, is that their survival depends upon the ability to raise themselves to subsistence level, like other Namibians, by supplementing their hunting and gathering with gardens, cattle, handicrafts, education, and employment.

Several thousand Ju/’hoansi still hunted large animals with poison arrows and gathered wild food in Namibia until the late 1950s. They lived in mobile bands of about forty, each group centered on a n'.ore—“the place to which you belong” or “the place which gives you food and water”—where their ancestors had lived for as many as 40,000 years.

In the past forty years, however, life has changed drastically for the Ju/’hoansi. They lost seventy percent of their traditional area, called Nyae Nyae, in 1970 when the South African administration carved the country up among ethnic groups, reserving much of it for the white minority. Nearly all Ju/’hoan bands migrated to the Bushmanland administrative center, Tjumlkui, where they were given a school, a clinic, a church, a jail, and a few jobs. But Ju/’hoansi called Tjumlkui “the place of death” for its overcrowding, alcohol-related violence, desperate poverty, and social disorganization. Their feelings for their n'.ores remained deep. “Your father’s father’s n'.ore is a place you do not leave,” says Tsamkxao /Oma, a forty-fiveyear-old Bushman who heads the Nyae Nyae Farmers Cooperative.

Some seven hundred Ju/’hoansi in twenty extended family groups have reestablished their communities at their ancient places in a program parallel to the “outstation” movement in Aboriginal Australia. Socially these communities are like the nomadic camps of previous days, but economically they are building a stable mixed economy of hunting/gathering, smallscale cattle raising, gardens, and handicrafts.

Ju/’hoan farmers struggle against lions that kill their cattle, elephants that trample gardens and pull out water pumps, and unhelpful or hostile officials who believe them incapable of development. They also struggle within themselves to adapt the cultural rules and values of their foraging life to an agricultural one. But most are adamant about not returning to the rural slum of Tjumlkui. “We must lift ourselves up or die!” people say to each other now. A new spirit of possibility is palpable in the cheerful, though struggling, communities.

Ju/’hoan efforts to raise themselves to subsistence level coincide with massive political changes as this country of 1.3 million people nears its long-awaited independence from South Africa. The old German colony of South West Africa, which South Africa has ruled since conquering it in 1915 during World War I, is Africa’s last colony. Renamed Namibia after the Namib Desert, it has recently (November 1989) completed United Nations-supervised elections for a constitution-writing assembly, has adopted a constitution (January 1990), and will gain sovereignty once the new government is in place, probably in April of this year.

The new government will inherit the legacy of apartheid, which deepened the economic and cultural divisions among the country’s eleven ethnic groups. Most Namibians, including Bushmen, live well below the poverty line even for the Third World. They depend heavily on a kin-based economy—one brother keeps cattle while another hunts; a cousin works in the city and brings goods home when he can. And they rely on rights to land and resources they don’t have to pay for.

Under South African rule, seventy percent of the Namibian population has been squeezed onto thirty percent of the land. The rest has been reserved for diamond mining, white-owned commercial farms, and tourism. The land set aside for Bushmen was reduced in 1978 from 45,000 square kilometers to 6,000 square kilometers, an area sufficient to support only 162 people by hunting and gathering alone. Without more intensive food production, Ju/’hoansi are doomed to remain wards of some government, dependent and vulnerable. All but 3,500 of Namibia’s 33,000 Bushmen live outside Bushmanland, working as laborers for white and black farmers or living on the edges of rural communities, dependent on the few family members with work.

The half-dozen groups of Namibians labeled as Bushmen were never united politically. They speak several languages, some mutually unintelligible, and live in widely separated areas of this vast desert country. They had no traditional chiefs or headmen and, thus, no regional government, as other ethnic groups had under South African rule.

Historically the Bushmen were exterminated as vermin; today there are still many people who regard them as lazy, unteachable, and constitutionally unable to plan for the future. They have remained at the bottom of every social ladder, a minority misunderstood by white and black alike.

But celebration of old ties to the land and to their culture is strong among Ju/’hoansi today. At a recent all-night dance under a clear black sky pricked with stars, men drummed and women went into healing trances and cured each other by traditional laying-on of hands. Di//xao ^Oma, Tsamkxao’s sister, her two-year-old bouncing in a sling on her back, suddenly left off singing and flung her hands toward the sky. A spectacular and inexplicable pencil of light was poised like a shot arrow among the stars, and it hung overhead for many seconds. “Yes!” she cried exultantly. “We’re dancing and our old, old people see us!”

The real voices of the Kalahari, Di//xao’s and others, have rarely been heard outside their own communities. However, as some of the world’s last hunter/gatherers, Ju/’hoansi have become a focus of scholarly and human interest. Their lifestyle provides clues to the ancient world from which our civilizations sprang. The “Ju/wa” or !Kung Bushmen are familiar to Americans through films such as The Gods Must Be Crazy (parts I and II) and through Elizabeth Marshall Thomas’s book The Harmless People. They became popular—but remained isolated.

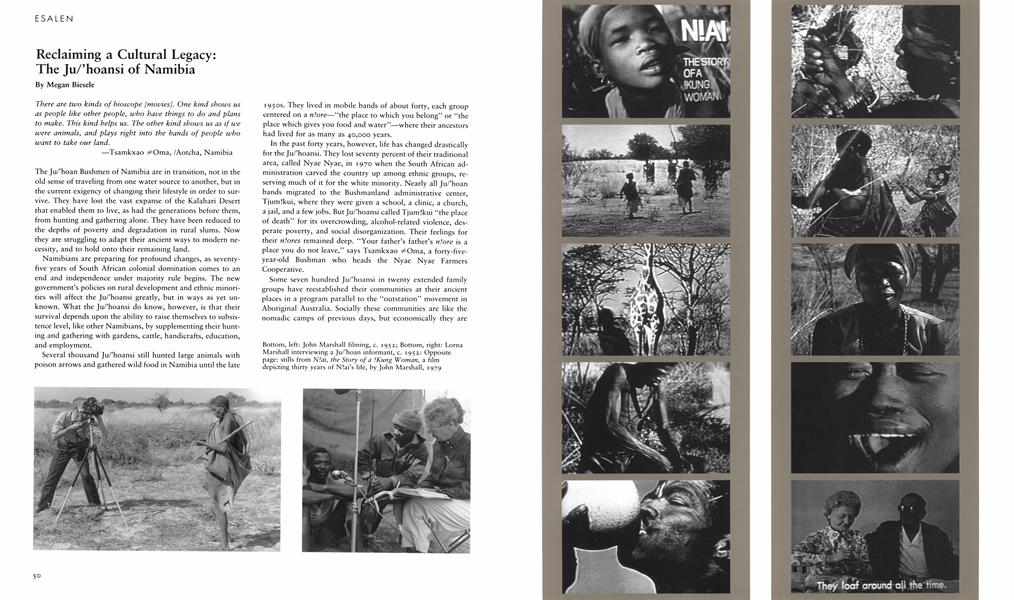

The American filmmaker John Marshall and his associate Claire Ritchie are now working on a depiction of the Ju/’hoansi that shows a very different side of their lives. After eight years of practical development work with the Ju/’hoan communities, Marshall and Ritchie have recently returned to their work as filmmakers to continue the process of documenting Bushman lives begun by Marshall’s family during the 1950s, and are assembling a film trilogy on the history of the Ju/’hoansi’s struggle for self-determination.

The history of Marshall’s forty years of film made with the Ju/’hoansi reads like a primer on the changes which have taken place in both human-rights awareness and in anthropology during the same period. Marshall’s films have moved from the “illustrative” to the “dramatic” (à la Robert Flaherty) and thence to cinéma vérité sequences, eventually culminating in a new style of committed, dialogic, and collaborative film endeavor. Increasingly, Ju/’hoansi themselves are aware of the importance of the process of depiction in presenting their situation to other people. As Tsamkxao /Oma said to a newspaperman recently, “I went to a conference in Cape Town last year and found that many people had never even heard of my people. If they do, that may be a way to help end discrimination. Those days we refuse that our children have to hear words like ‘Bobiaan’ [baboon] and ‘Kaffir’.”

News of coming Namibian independence startled Ju/’hoansi into political involvement. Through community discussions, this egalitarian people has begun to think of selecting its own representatives and of seeking legal recognition for its ancient system of land use. Members of the Nyae Nyae Farmers Cooperative, a Ju/’hoan community self-help organization, went “on the road,” traveling the sometimes impassable tracks of their contiguous n’.ores to bring the news to far-flung communities, not one of which boasts a radio.

One clear, hot morning, cooperative chairman Tsamkxao /Oma set off early with four companions to drive through heavy sand to communities in the far north. He was wearing a new suit purchased to match the formality of the occasion. When a kudu ran across the track he braked, flung off the coat and his shoes, grabbed his bow and quiver of poison arrows, and went off where the antelope had disappeared. In a few minutes he was back at the truck, replacing unused arrows in the quiver. The arrow in the kudu would do its work slowly and Tsamkxao would return later to track the dying animal. He put his coat back on and resumed the business day.

At the community of N//oaq!’osi, the meeting was held in the shade near a circle of small huts made of sticks and fresh grass. Tsamkxao and the people with him talked about political meetings in Windhoek, the capital, 750 kilometers away.

The talks about elections and other democratic concepts were held outdoors, mostly, with a tree or a shelter of sticks and leaves for shade, or under a pole framework with wild melons sliced and drying overhead. People sat on old blankets or on the silver-grey sand. One day, when the wind was blowing violently and conversation was impossible outdoors, the travelers were forced into tiny mud houses, where entire communities sat on top of each other to hear the news.

At Djxokho, people were delighted to receive the news about the coming independence. “This almost sounds like real help,” one man said. A young man named G/aqo asked to speak. Dressed in a South African Defense Force cap and boots, he spoke Fanagalo, the lingua franca he learned in the South African gold mines. With his wider experience and his language skills, he explained to his relatives the laws under which Ju/’hoansi lost so much control over their lives. He added that the Djxokho community had recently complained to the commission that tourists had been fouling their drinking water. A woman named Tsheg//ae added, “I went to talk to these two whites. And I saw that they had stopped their car and entered the reservoir and were swimming. And I said, ‘Yo, why have you jumped into our drinking water and put your dirt into it?’ And these school-kids got their car number; we had no pencil but they wrote it down with a cinder.”

After a while the team packed up to continue the trip. At two other communities that day, the information was passed on and discussed. Having a forum in which to air their grievances seemed to lighten people’s hearts, and the trip took on a festive atmosphere.

Ju/’hoansi call themselves “the owners of argument” and “the people who talk too much.” For them it’s important that issues be discussed and debated by all. None of the language of democracy seems new among them; rather it is age-old. These are the people who gravely said to anthropologist Richard Lee over a decade ago, “We have no headmen; each one of us is a headman over himself.” The concept of “one person, one vote” fits right in with their ideology, and, among these sexually egalitarian people, one doesn’t have to add, “and a woman’s vote is just like a man’s.”

Since 1986 the Ju/hoan communities have worked to make the Nyae Nyae Farmers Cooperative a democratic organization responsible for many decisions about their development: the establishment of new communities; the location of boreholes; the distribution of cattle to start small herds; and the use of money from overseas organizations. The cooperative has also begun to take on more general political functions, acting, in the absence of a traditional chief, as a communications channel to the administration on issues such as tourism and the local school. It also brings in information that the communities need to hear.

Assumptions not only of uninformed neighbors but of the West’s whole science of looking at such people—anthropology—are involved in the question of their future. Anthropology is only now wrestling itself out of the pervasive nineteenthcentury romanticism which has characterized Western views of indigenous peoples. One mode of representative romanticism, called “ethnographic pastoral” by postmodern cultural critic James Clifford, has been the style of choice for much verbal describing and picturing of hunting-gathering peoples such as the Bushmen.

Pastoral imagery often shows the lion lying down with the lamb; what results from such a vision when people are portrayed, though, is the suppression both of lively individuals and of the oppressive political realities which confront them. People can despair and quietly die while mythic media paint them as happy savages. Outsiders can perceive them as “children of the earth” with no real need of legal title to land. Myths can relentlessly cast persons living today into a “present becoming past,” so that they quite literally disappear before our eyes. Meanwhile, people like the Bushmen are actually engaged in a complex, creative “past becoming future” which is central to their acquisition of personal and political power.

Audiovisual and written media, under the stimulus of what may be called a “revolution of reflexivity” in the social sciences, are becoming increasingly sensitive to issues of representation itself—to devices used to frame and slant depictions; to unacknowledged agendas behind representation; to sexist, racist, ethnic, and class stereotyping; to the suppression of individuality in the search for the “typical”; and to the pernicious romanticism of “timeless” portrayals of the other. Reflexivity, the idea that any grasp of other cultural realities is colored and shaped by our own background assumptions, has had a profound effect on anthropology and documentary media.

Because media have been particularly quick to romanticize these people, the situation of the contemporary Ju/’hoansi and other Bushmen of Namibia has been referred to by John Marshall as “Death by Myth.” Their recent history exemplifies the practical problems raised for a developing people by seductive, outmoded representations in both anthropological and popular media. Lately things have begun to change; presentations of these people have begun to move from simplistic, fairytale depictions to multivoiced, complex, often contradictory but always active self-presentations. There is in postmodern social documentation a thorough challenge to naive positivism, and progress toward the reenshrinement of narration as a more natural mode of description than the controlling, expository modes of science. In this new view, the “other” is seen as a person who is continually making sense of himself for himself, and increasingly the observer is included in both the event and its record: in other words, there is progress toward creating common cause in all representations, which are themselves seen as social and political facts.

When someone says, “You Bushmen have no government,” we’ll say that our old, old people long ago had a government, and it was an ember from the fire where we last lived which we used to light the fire at the new place where we were going.

These words of Di//xao ^Oma, a regional chairwoman of the Nyae Nyae Farmers Cooperative, show that anthropology’s assumptions must necessarily be altered by the experience of really listening, perhaps for the first time, to the words of anthropology’s “informants.” And listening in the context of shared development activities is doubly productive of real hearing. Anthropology stands to profit greatly from the learning available to it through development projects like the Ju/wa Bushman Development Foundation.

For one thing, experiencing the energy of a people’s confrontation with each other in the process of transforming their society provides irreplaceable chances to learn the multiple sides to each question. Ju/’hoansi struggle with many external things, like lions, elephants, and hostile officialdom. But their main struggle is with themselves, as they feint and parry with old ideas, adapting the cultural rules and values that underwrote the old foraging way of life to their chosen, very different one of agriculture.

Marshall and Ritchie’s forthcoming film trilogy will show, as still photographs underscore, how the Bushmen people are creatively engaged with their problematic present life. Neither medium, however, would have been able to portray these realities without the sense of mutual trust produced by the Ju/wa Bushman Development Foundation’s decade of advocacy and intervention.

Founded in 1981 by Marshall and Ritchie, the JBDF is a nonprofit organization based at Windhoek, Namibia, which is dedicated to supporting the self-development of Ju/’hoan and other Bushman peoples of Namibia. A sister organization for neighboring Botswana Bushmen, the Kalahari Peoples Fund, was started in 1973 by members of the Harvard Kalahari Research Group. Both organizations have pursued programs of self-help support to Bushman communities which are specifically designed to use the best available anthropological knowledge in service of the people.

The JBDF provides aid in a variety of forms to communities in the Nyae Nyae area. First, it offers support in developing the physical infrastructure needed to develop the mixed local economy (small stock-keeping and dryland gardening, in addition to hunting and gathering), with the Ju/’hoansi supplying the labor needed to install it. This infrastructure includes boreholes and handor wind-pumps, to which roads are built by community labor; fencing wire for kraals and cattle crushes, whose poles are cut by community labor; small lots of cattle, all of the work of which depends on community organizing and labor; and vehicles which make possible the convening of Farmers Cooperative meetings from all twenty of the established communities at a central point.

Up to the time of the first free election in Namibia, the JBDF’s activities mainly involved community and economic development, and the fostering of communicational skills. Recently it has begun a program of related educational and training projects to enable the Ju/’hoansi to control their own self-sufficient, mixed economy. Much of the work has involved talking and listening as Ju/’hoansi work through the puzzling new problems which face them.

As an anthropologist taking part in this project, I find it a great privilege to participate in a mutual endeavor that involves making sense of a rapidly changing world. We are all, after all, caught in the same dilemma of constructing meaning and order out of fragments of the myths we’ve held about ourselves. Culture never rests, whether it is technological or “traditional.” It develops, and people develop themselves, just as the culture of imaging people itself develops, in the darkroom of the mind as well as in the light of shared work. As one Bushman woman, !Kun/obe Nla’an, expressed it, “If you have work to do you have to do it. If you’re behind you have to catch up. It’s not a Ju/’hoan thing, it’s a human thing.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

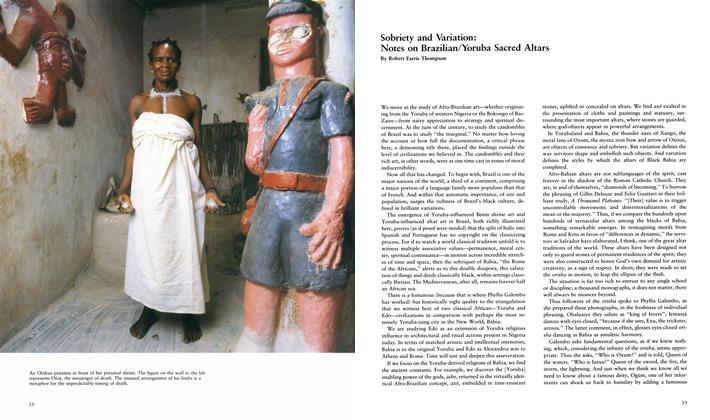

Sobriety And Variation: Notes On Brazilian/yoruba Sacred Altars

Early Summer 1990 By Robert Farris Thompson -

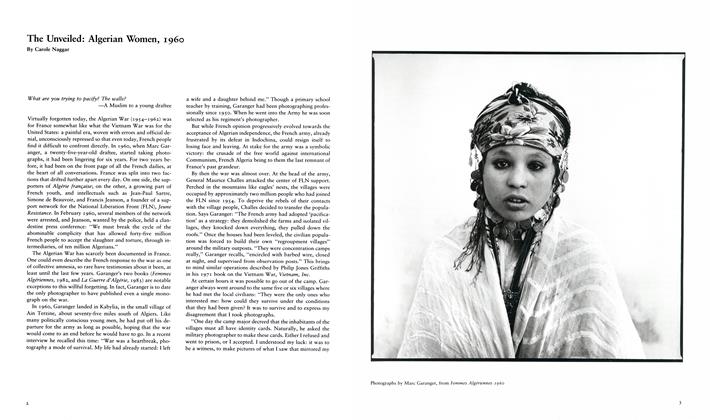

The Unveiled: Algerian Women, 1960

Early Summer 1990 By Carole Naggar -

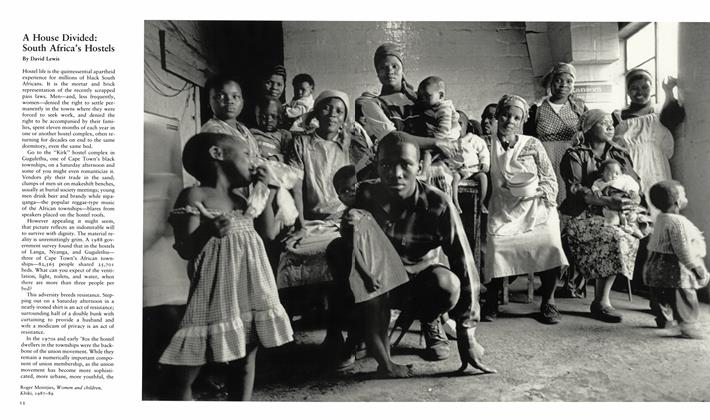

A House Divided: South Africa's Hostels

Early Summer 1990 By David Lewis -

Esalen

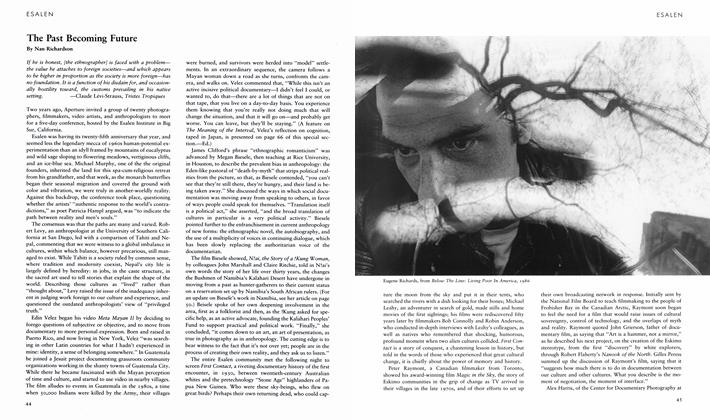

EsalenThe Past Becoming Future

Early Summer 1990 By Nan Richardson -

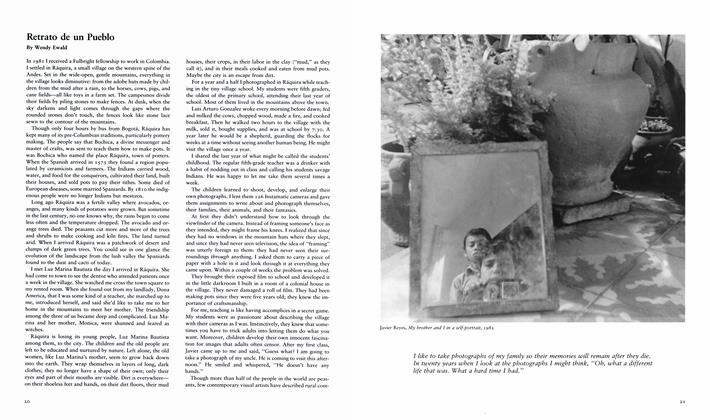

Retrato De Un Pueblo

Early Summer 1990 By Wendy Ewald -

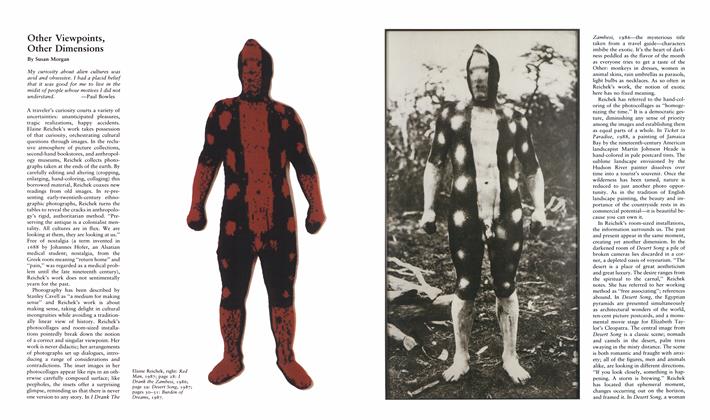

Other Viewpoints, Other Dimensions

Early Summer 1990 By Susan Morgan

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Esalen

-

Esalen

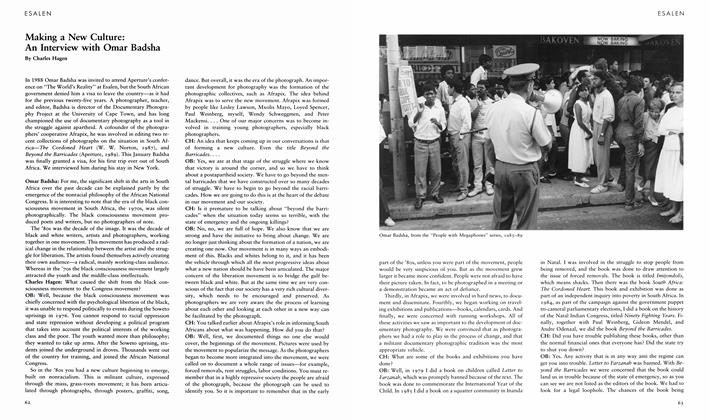

EsalenMaking A New Culture: An Interview With Omar Badsha

Early Summer 1990 By Charles Hagen -

Esalen

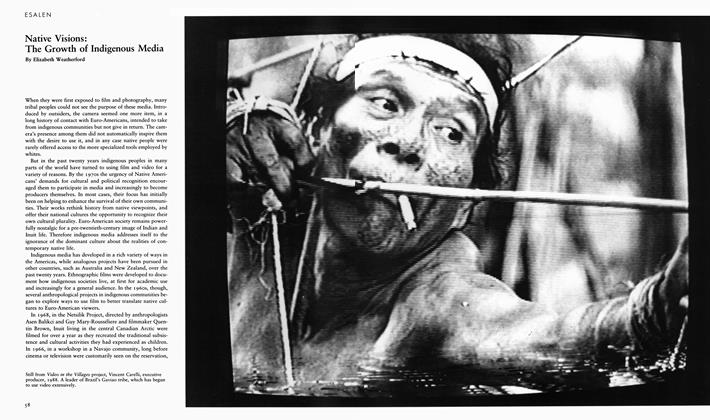

EsalenNative Visions: The Growth Of Indigenous Media

Early Summer 1990 By Elizabeth Weatherford -

Esalen

EsalenOf Wood And Stone

Early Summer 1990 By Karoline Postal-Vinay -

Esalen

EsalenThe Past Becoming Future

Early Summer 1990 By Nan Richardson