A House Divided: South Africa's Hostels

David Lewis

Hostel life is the quintessential apartheid experience for millions of black South Africans. It is the mortar and brick representation of the recently scrapped pass laws. Men—and, less frequently, women—denied the right to settle permanently in the towns where they were forced to seek work, and denied the right to be accompanied by their families, spent eleven months of each year in one or another hostel complex, often returning for decades on end to the same dormitory, even the same bed.

Go to the “Kirk” hostel complex in Gugulethu, one of Cape Town’s black townships, on a Saturday afternoon and some of you might even romanticize it. Vendors ply their trade in the sand; clumps of men sit on makeshift benches, usually at burial society meetings; young men drink beer and brandy while mpaqanga—the popular reggae-type music of the African townships—blares from speakers placed on the hostel roofs.

However appealing it might seem, that picture reflects an indomitable will to survive with dignity. The material reality is unremittingly grim. A 1988 government survey found that in the hostels of Langa, Nyanga, and Gugulethu— three of Cape Town’s African townships—82,565 people shared 25,701 beds. What can you expect of the ventilation, light, toilets, and water, when there are more than three people per bed?

This adversity breeds resistance. Stepping out on a Saturday afternoon in a neatly ironed shirt is an act of resistance; surrounding half of a double bunk with curtaining to provide a husband and wife a modicum of privacy is an act of resistance.

In the 1970s and early ’80s the hostel dwellers in the townships were the backbone of the union movement. While they remain a numerically important component of union membership, as the union movement has become more sophisticated, more urbane, more youthful, the participation of hostel dwellers in its leadership has diminished. The recent Congress of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa—one of the largest black unions in the country— committed the union to drawing hostel dwellers back into active participation in the unions.

In several areas the hostel dwellers have organized themselves in their residential areas. One of the most effective of these is the Western Cape-based Hostel Dwellers Association. Tapping into the formal and informal networks that stretch back into the various Bantustans, and acutely sensitive to the peculiar needs and style of its constituency, the Hostel Dwellers Association boasts some 14,000 members.

The pass laws have been repealed for three years now. Women and children have flooded into the cities. Single beds house entire families. The major effect on the hostels has been even greater neglect at the hands of the state. The state has converted several hostels into family accommodations, moving hostel dwellers out, replacing them from the long waiting lists for housing from the townships. The Hostel Dwellers Association is involved in an ambitious scheme to provide accommodations to the hostel residents and their families. However, the state’s preferred mode of accommodating those on the bottom rungs of the economic ladder has shifted from hostels to the squatter camps—“informal settlements,” in current officialese—springing up on the peripheries of the major cities.

But migrancy and the hostels will not go away in the near future. And so the struggle of the hostel residents will continue. For many hostel dwellers there remain strong social and economic ties to the rural area; many cannot move with their family to the squatter camps in the cities. Many don’t want to move. I once asked one of the leaders of the Hostel Dwellers Association how he saw his role in a liberated South Africa. “In the South African parliament, of course,” he replied; “MP for Idutywa, Transkei.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

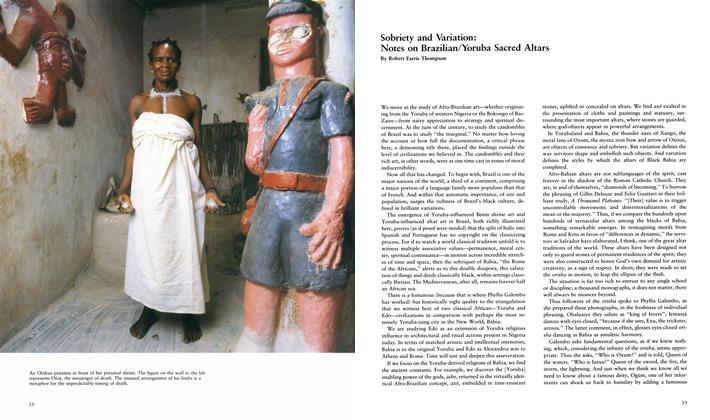

Sobriety And Variation: Notes On Brazilian/yoruba Sacred Altars

Early Summer 1990 By Robert Farris Thompson -

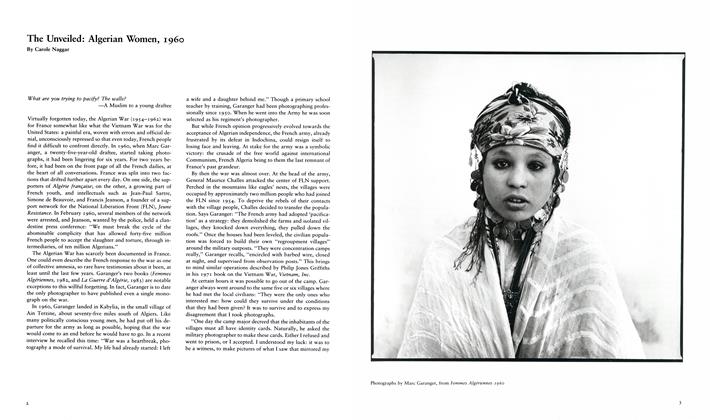

The Unveiled: Algerian Women, 1960

Early Summer 1990 By Carole Naggar -

Esalen

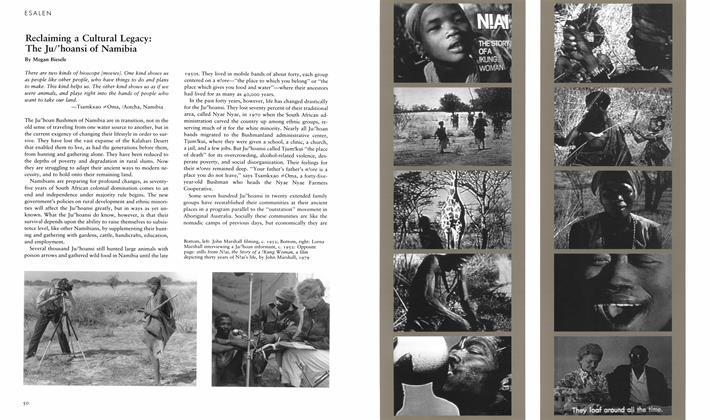

EsalenReclaiming A Cultural Legacy: The Ju/'hoansi Of Namibia

Early Summer 1990 By Megan Biesele -

Esalen

EsalenThe Past Becoming Future

Early Summer 1990 By Nan Richardson -

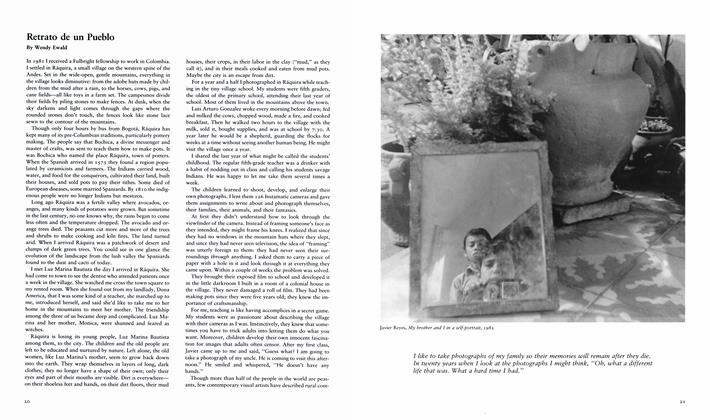

Retrato De Un Pueblo

Early Summer 1990 By Wendy Ewald -

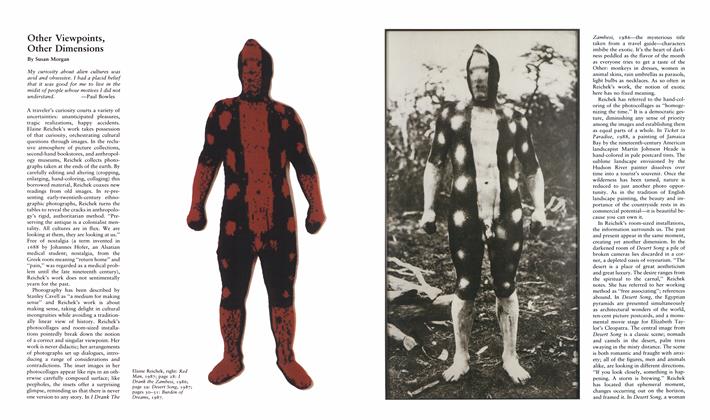

Other Viewpoints, Other Dimensions

Early Summer 1990 By Susan Morgan