Unbounded Wilderness

Barry Lopez

The fate of the American landscape, its ponds and hollows, its creeks and forests, its prairies, wet glades, and canyons, cannot be addressed solely in terms of "wilderness" or be solved by "wilderness preservation." What we face now in North America—and, of course, elsewhere—is a crisis in land use, in how we regard land.

With the impending failure of vast but finite underground aquifers, the loss of animals and topsoil, and the intractability of certain forms of pollution, it has become clear that we need to rethink our relationship to the entire landscape. How we farm, where we place roads, how we design cities, limit real estate development, and how we mine, fish, and log are all now crucial questions. To have this fundamental problem of land ethics defined, or understood, as mainly “a fight for wilderness” hurts us in two ways. It preserves a misleading and artificial distinction between “holy” and “profane” lands, and it continues to serve the industries that most seriously threaten wilderness. By focusing public attention on “a fair division” of the relatively few parcels of land that are still candidates for wilderness designation, and on the roughly two percent of federal land that has already been locked up (in their phrase), these industries hope to continue to mine, log, dam, graze, and drain the remaining ninety-six percent of federal land with minimal interference. Many of them cynically assume, in addition, that what has been locked up can, and will, be opened up.

The kind of management plan the extractive industries do not want to hear—and so far they haven’t had to—is one based on responsible use, not this false dichotomy. As long as the argument remains “wilderness” versus “non-wilderness,” the timber industry (the only extractive industry excluded from wilderness areas) will be happy to appear gracious in trading two high-altitude, rockbound parcels of land suitable for wilderness designation for one parcel of low-altitude forest land. The real issue—the responsible management of all land—remains obscured. And the apparent graciousness of the timber industry’s gesture founders when, with stunning hypocrisy and insensitivity, it expresses “concern” because wilderness areas may exclude the handicapped.

What we face is a crisis of character. Our relationships with the land are essentially still colonial—exploitive, indifferent, romantic, and cruel. They are largely untouched by a sense of wonder or by the sense of a universe shaped by other than human perception and orderings. We are, it is possible to argue, blind to creation; we do not scruple or hesitate to improve upon it or to disturb it.

In wilderness, the threads of evolution and all the synapses of the food web, theoretically, are free of the social and economic schemes of human beings. Ozone depletion, acid rain, and the labyrinthine cycling of manmade chemicals through the food chain make this intended ideal something of a romance, but we persist in securing wilderness—taking land out of the cycle of manufacturing—for excellent reasons, both moral and practical. Haunted by a sense that we do not have the right to appropriate everything, we seek, on moral grounds, to leave some land untouched (and even to repair or make restitution through the relocation and réintroduction of species). And hearing, for example, of the utility of some exotic plant in treating cancer, we see a practical advantage in leaving these “blueprint” landscapes undisturbed.

Our desire to preserve wild places is, unarguably, wise; and the fight to preserve them is waged furiously now all over the world. (A striking difference in these separate battles is the extent to which low-tech, small-scale human life is incorporated into the meaning of wilderness in various cultures.) But the fight for wilderness is a holding action. The social and economic forces that would dismantle wilderness are, again, pleased to focus a public relations campaign or their considerable political and legal power on this narrow front. It is on a broader, overriding front, the responsible management of public and private lands for future generations, that they do not wish to be challenged. Such management would include candor about the social cost of dams, the second, poisonous life of mine tailings, and the methodical killing of black bears to protect stands of commercial timber.

We need another kind of relationship with the earth, a wiser, humbler, more deferential association, a more informed reciprocity. We share a biology. If we have a decision to ponder now, it is how to (re)incorporate the lands we occupy, after millennia of neglect, into our moral universe. We must incorporate not only our farmsteads and the retreats of the wolverine but the land upon which our houses, our stores, and our buildings stand. Our behavior, from planting a garden to mining iron ore, must begin to reflect the same principles.

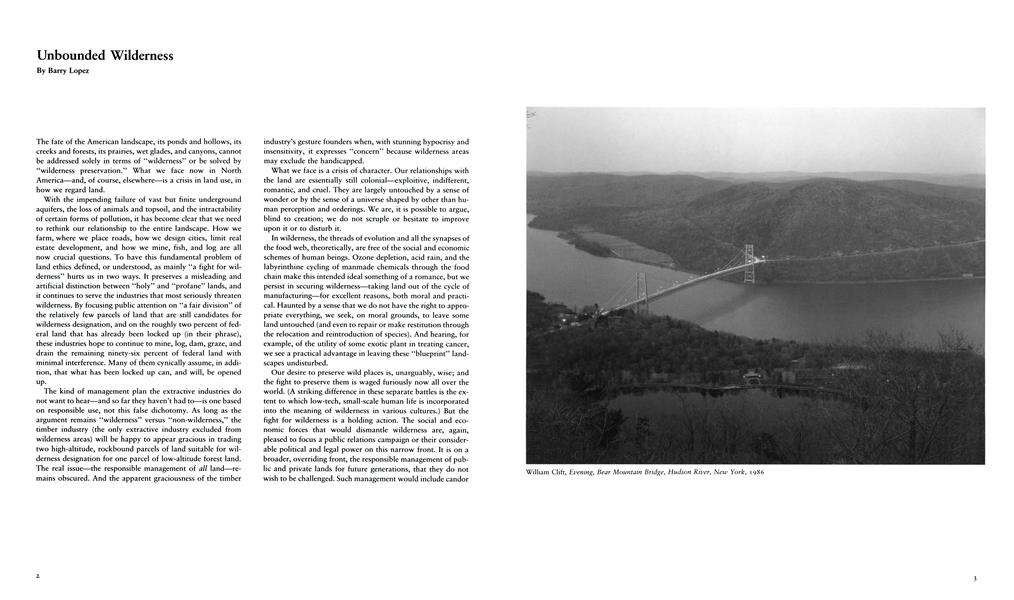

In an essay called “Photographing Evil,” the photographer Robert Adams addresses issues of artistic responsibility and social reform and considers photography’s limits in dealing with the “certainty of evil.” A curious reverberation in this essay is how, in his own photographs, Adams captures our corrosive relations with the land. He does so, in part, by avoiding the summary effect, the exclusionary aspect, of “pinup” nature photography. It is easier, certainly, to photograph what is beautiful in nature than what is dark, but the desire to see the other side of nature is a longing for wholeness we need to attend to. We need to see the wildness in wilderness if we are ever to grasp our differences and concordances with nature. Similarly, in considering how we will care for the earth (i.e., how we will care for ourselves), we must broaden our definition of landscape writing and landscape photography to include more than visions of wilderness and sojourns in wild lands. Such writing and photography must now convey the sense of an unbroken pattern of land and our responsibility for maintaining a commensal relationship with it.

The value of de facto and de jure wilderness is indisputable, and the need to protect it is essential. But the deeper, more pervasive issue—how we farm, how we log, how we fish— includes this intelligence. Our crisis is not a crisis of technology or law, of administration or professional skill, but a crisis of culture. The predicament has been elucidated straightforwardly in the work of Aldo Leopold, Rachel Carson, the late Lewis Mumford, the late Edward Abbey, and perhaps most forcefully in the work of Wendell Berry. The thinking is not esoteric or radical. A cursory reading of ethnographic reports from around the earth makes it clear that the aberration in human history is recent, short, and ours—a geography stripped of dignity and ethical responsibility.

Wild landscapes are necessary to our being. We require them as we require air and water. But we need, at the same time, to create a landscape in which wilderness makes deep and eminent sense as part of the whole, a landscape in which wilderness is not an orphan. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

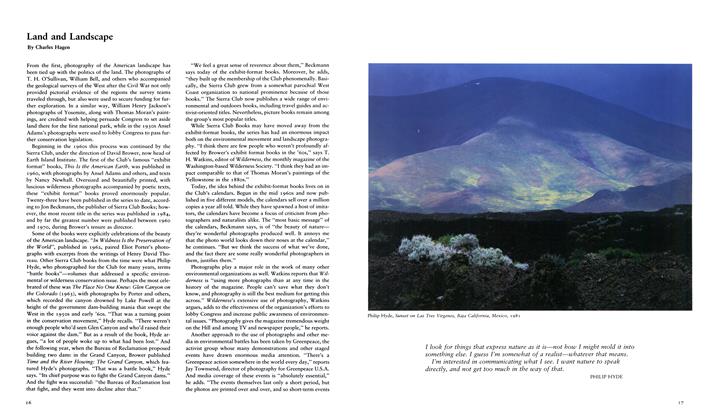

Land And Landscape

Late Summer 1990 By Charles Hagen -

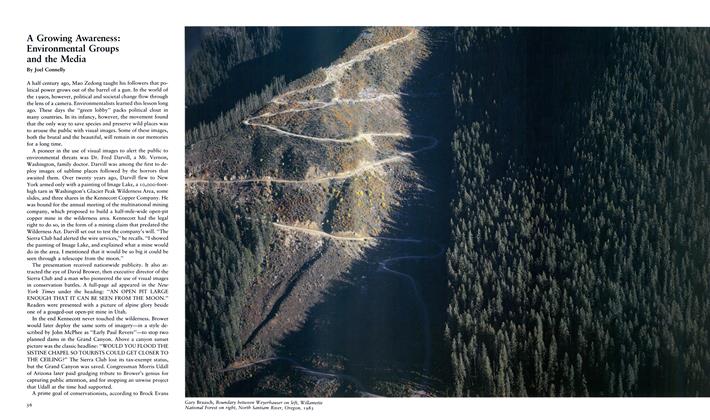

A Growing Awareness: Environmental Groups And The Media

Late Summer 1990 By Joel Connelly -

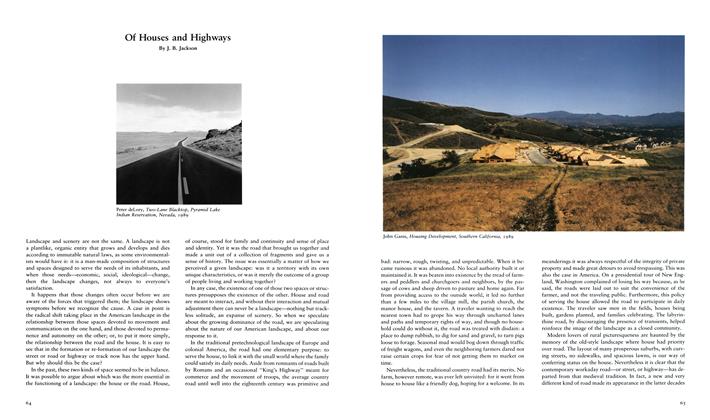

Of Houses And Highways

Late Summer 1990 By J. B. Jackson -

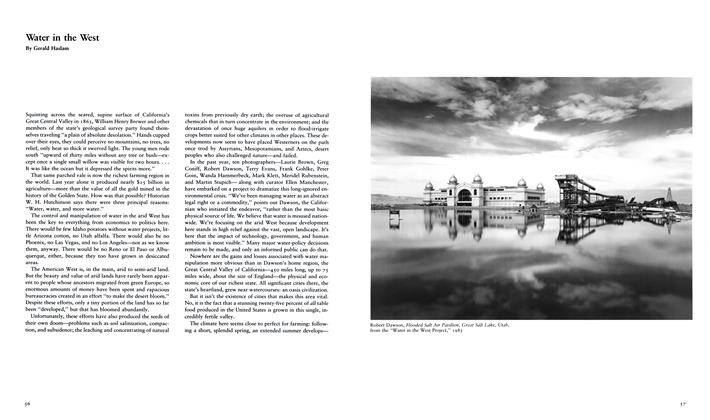

Water In The West

Late Summer 1990 By Gerald Haslam -

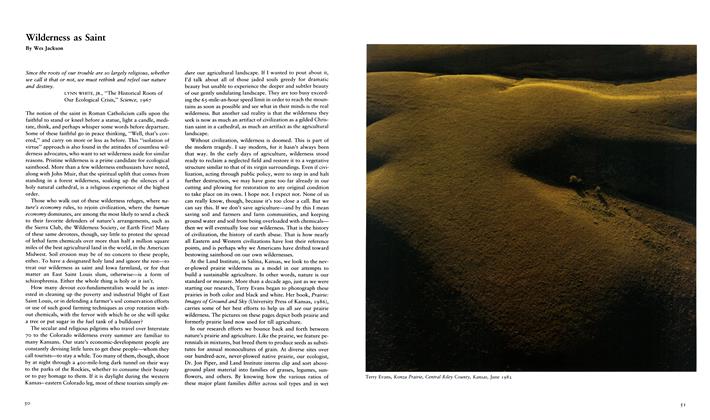

Wilderness As Saint

Late Summer 1990 By Wes Jackson -

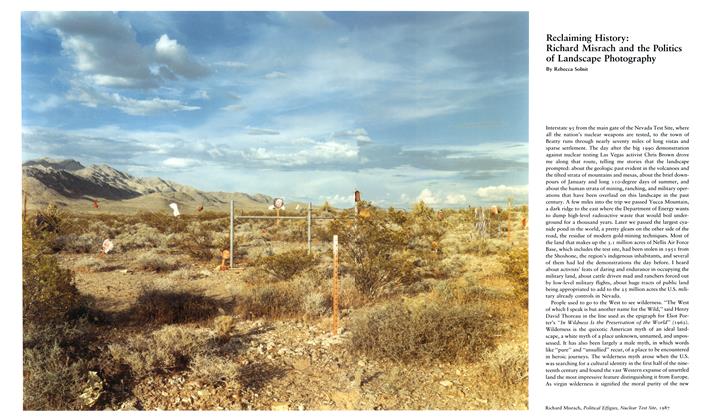

Reclaiming History: Richard Misrach And The Politics Of Landscape Photography

Late Summer 1990 By Rebecca Solnit