A Growing Awareness: Environmental Groups and the Media

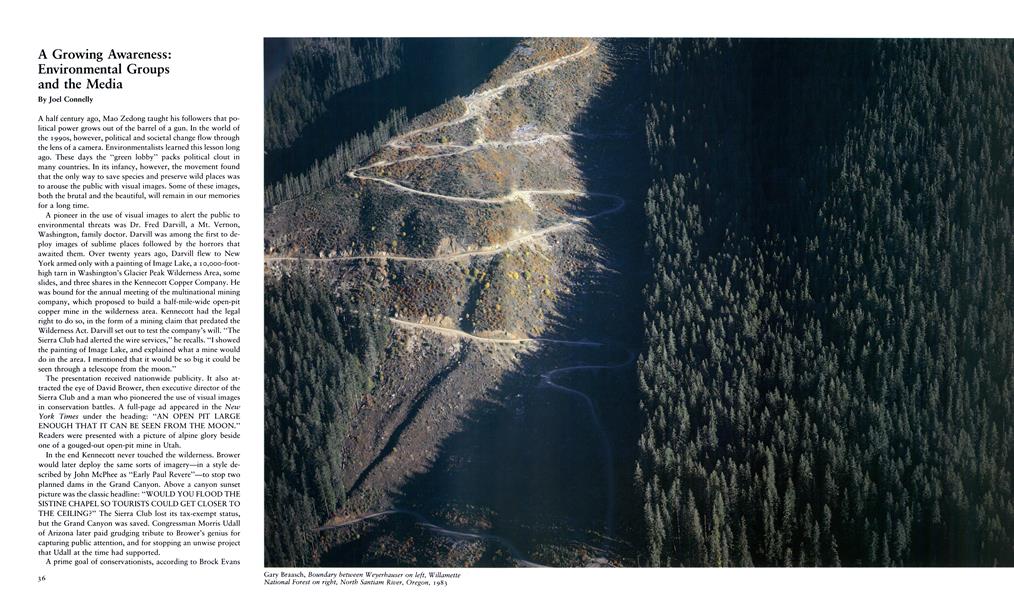

Joel Connelly

A half century ago, Mao Zedong taught his followers that political power grows out of the barrel of a gun. In the world of the 1990s, however, political and societal change flow through the lens of a camera. Environmentalists learned this lesson long ago. These days the “green lobby” packs political clout in many countries. In its infancy, however, the movement found that the only way to save species and preserve wild places was to arouse the public with visual images. Some of these images, both the brutal and the beautiful, will remain in our memories for a long time.

A pioneer in the use of visual images to alert the public to environmental threats was Dr. Fred Darvill, a Mt. Vernon, Washington, family doctor. Darvill was among the first to deploy images of sublime places followed by the horrors that awaited them. Over twenty years ago, Darvill flew to New York armed only with a painting of Image Lake, a 10,000-foothigh tarn in Washington’s Glacier Peak Wilderness Area, some slides, and three shares in the Kennecott Copper Company. He was bound for the annual meeting of the multinational mining company, which proposed to build a half-mile-wide open-pit copper mine in the wilderness area. Kennecott had the legal right to do so, in the form of a mining claim that predated the Wilderness Act. Darvill set out to test the company’s will. “The Sierra Club had alerted the wire services,” he recalls. “I showed the painting of Image Lake, and explained what a mine would do in the area. I mentioned that it would be so big it could be seen through a telescope from the moon.”

The presentation received nationwide publicity. It also attracted the eye of David Brower, then executive director of the Sierra Club and a man who pioneered the use of visual images in conservation battles. A full-page ad appeared in the New York Times under the heading: “AN OPEN PIT LARGE ENOUGH THAT IT CAN BE SEEN FROM THE MOON.” Readers were presented with a picture of alpine glory beside one of a gouged-out open-pit mine in Utah.

In the end Kennecott never touched the wilderness. Brower would later deploy the same sorts of imagery—in a style described by John McPhee as “Early Paul Revere”—to stop two planned dams in the Grand Canyon. Above a canyon sunset picture was the classic headline: “WOULD YOU FLOOD THE SISTINE CHAPEL SO TOURISTS COULD GET CLOSER TO THE CEILING?” The Sierra Club lost its tax-exempt status, but the Grand Canyon was saved. Congressman Morris Udall of Arizona later paid grudging tribute to Brower’s genius for capturing public attention, and for stopping an unwise project that Udall at the time had supported.

A prime goal of conservationists, according to Brock Evans of the National Audubon Society, has been to nationalize and even internationalize key battles. “Visual images are the key for us,” says Evans. “They’ve kept ancient forests standing and oil rigs out of the Arctic Refuge.” Cameras connect the global village. Viewers thousands of miles away can watch pictures of thousand-year-old Sitka spruce trees falling under a logger’s chain saw. They can see oil-covered otters being lifted from Prince William Sound. They can feel the fear of those on a Greenpeace zodiac boat as Soviet whalers fire a harpoon over its bow to mortally wound one of the world’s largest marine mammals. Such pictures can generate thousands of words in citizen anger, enough to sway Congress or force the new president of Brazil to name an environmentalist to his cabinet.

When the Exxon Valdez fouled Prince William Sound, it disrupted a slick campaign aimed at persuading Congress to allow oil drilling in Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Oil lobbyists had effectively argued the necessity of reducing dependence on foreign petroleum. Environmentalists had been unable to sway the public with pretty pictures of caribou. But images of oil-soaked beaches, birds, and seals triggered outrage. Alaska Senator Ted Stevens put it best: the Exxon Valdez spill had set drilling back at least two years. Asked when it would resurface, he replied: “When the oil spill is no longer news.”

Direct action has proven a potent way to focus the camera on environmental events. “The Fox” was its prophet. This anonymous ecological saboteur stalked Chicago in the late 1960s. He never showed his face, but publicized his deeds with calls to TV stations and explained his outrage to columnist Mike Royko. Refineries found their outfalls plugged. Banners were hung from smokestacks. The Fox even invaded the executive offices of a steel company to dump smelly effluent on its carpets.

Over twenty years later, the Fox is frequently copied. Greenpeace protestors recently decorated a stack at the Longview Fiber Company pulp mill in Washington, on the Columbia River. When the press arrived, the activists were ready with documentation of dioxin dumping into one of North America’s great rivers.

Direct action is sometimes condemned by mainstream environmentalists who stress action through Congress and the courts. But confrontations can purchase time. In rain forests along the Northwest coast, the radical environmental group Earth First! has plunked down protesters in ancient trees marked for logging. When hauled down and arrested, they’ve given such names as “Doug Fir” and “Bobcat.” These tree-ins have generated nationwide attention and slowed the pace of logging.

A daring, filmed protest can focus attention on activities that some might wish to remain unnoticed. The Greenpeace Foundation was formed in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1971, an outgrowth of protests aimed at planned U.S. nuclear tests in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands. In 1973 Greenpeace began stalking bigger game—atmospheric nuclear tests being conducted by the French. Greenpeace vessels were boarded by the French navy, and crew members beaten. But the protesters kept sailing into test zones, and kept arguing that radiation posed a danger to peoples of the South Pacific. In 1986 French commandos sank a Greenpeace ship as it prepared to sail from a New Zealand harbor. One crew member was killed. The resulting uproar strained French relations with New Zealand, drove the French defense minister to resign, and cast France in the role of international outlaw.

Greenpeace has chosen the camera lens as its weapon for a variety of environmental crusades. “We go to the scene of a crime and bring back images of what’s going on,” says Alan Reichman, ocean ecology director for Greenpeace International. “In that way we mobilize public concern and pressure. We’re not talking abstractions and descriptions. We’re showing a factory ship which cuts up whales. We’re showing marine mammals trapped in nets. We’re showing what comes out of pulp mills.” Reichman has helped create memorable images.

He was part of a flotilla of zodiac boats that tried to stop a supertanker test run up the Strait of Juan de Fuca between British Columbia and Washington. Airborne photographers had a field day as the tiny craft buzzed around the 185,000-ton oil ship. A maneuverability test by the U.S. Coast Guard was turned into a political confrontation over whether to permit supertankers in sensitive West Coast estuaries.

A Greenpeace photo service makes pictures available to news sources, and engages in visual lobbying on Capitol Hill. Members of Congress, aides, and press gathered in a Longworth Building office last year to watch films of dolphins and birds entangled in the thick mesh of driftnet fishing lines. The seventy-mile-long driftnets are set on the North Pacific by Japanese and Taiwanese fishermen, supposedly to catch tuna and squid. In real life, they snare thousands of birds, marine mammals, and salmon. Congress has since pressed a reluctant Bush administration to support a worldwide ban on driftnet fishing.

The media savvy of such groups as Greenpeace has reached the environmental mainstream. The Natural Resources Defense Council has generally stayed far removed from visual imagery: its battles have been fought in court, notably with suits that have forced the U.S. Department of Energy to abide by the nation’s environmental laws in operating its nuclear weapons plants. On February 26, 1989, though, NRDC entered the court of public opinion. It gave CBS’s “60 Minutes” a study entitled “Intolerable Risk: Pesticides in Our Children’s Food.” One of the pesticides in the report was daminozide (trade name Alar), a chemical sprayed on apples to improve their color, crispness, and shelf life. In its study, NRDC predicted that Alar might cause one case of cancer for every 4,200 preschool children—a rate of risk 240 times the standard considered acceptable by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Although written by scientists, “Intolerable Risk” translated well to the TV screen. “60 Minutes” focused on Alar. Americans saw apples being sprayed in fields. They watched those apples going into baby food. And a day later, Oscar-winning actress (and parent) Meryl Streep went before a Senate hearing to argue the case for a ban on Alar. During the week following the “60 Minutes” report, apple sales fell fourteen percent, and industry losses were estimated at over $100 million. A few months later, Uniroyal Chemical, Inc., announced it was taking the .product off the market.

The media determines what is seen, and often what is saved. Photographs taken in a remote corner of northwest Wyoming helped create Yellowstone National Park over a century ago. Pictures can also lift politicians’ sights up from ledger sheets. The U.S. Forest Service urged a veto of 1976 legislation creating a 393,000-acre Alpine Lakes Wilderness Area in Washington, arguing that it would cost too much to acquire private lands. Washington Governor Dan Evans, an avid backpacker, carried a picture book into an Oval Office meeting with President Gerald Ford. Evans turned to photos of the Enchantment Lakes region and told of guiding his three young sons over rugged, 7,800-foot Aasgard Pass during a violent storm. “Dan, we’ve got to save it,” said Ford. He signed the bill.

As a writer I hate to admit it, but the camera’s lens can be more powerful than the writer’s pen. A physical confrontation convinced me. The state had let a logging contract on one of the few stands of old-growth trees left on Whidbey Island in Washington’s scenic Puget Sound. Island environmentalists vowed to block the logging. I stood at the end of a narrow logging track with Mark Anderson, a young photographer with KING-TV in Seattle. A logging rig rumbled into view; protesters sat down in its path, and Anderson began filming. The truck stopped. After much waving of arms, the loggers retreated. A few hours later, KING carried an unforgettable film of trucks and bodies. It followed up with a film of the undisturbed forest. Birds chirped and sunlight wafted through 500year-old trees. Anderson grew up in a logging town and knew the difference between a natural scene and a “working forest.” Logging plans were promptly suspended.

The lawyering over Whidbey’s forest was long and tedious. Not long ago, however, I enjoyed a walk among those same ancient trees, now—thanks at least in part to the powerful images presented by KING-TV and others—part of South Whidbey State Park.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Unbounded Wilderness

Late Summer 1990 By Barry Lopez -

Land And Landscape

Late Summer 1990 By Charles Hagen -

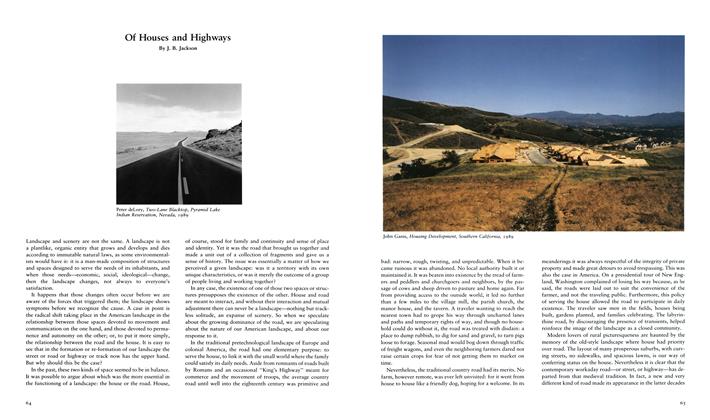

Of Houses And Highways

Late Summer 1990 By J. B. Jackson -

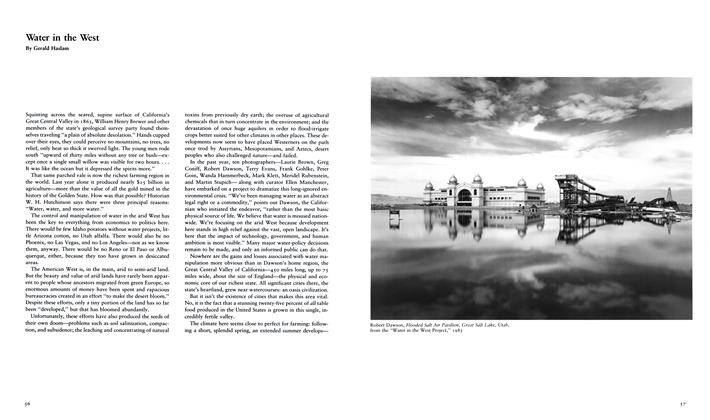

Water In The West

Late Summer 1990 By Gerald Haslam -

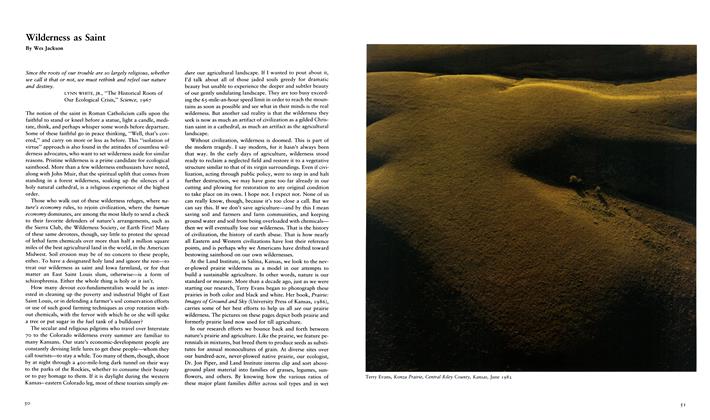

Wilderness As Saint

Late Summer 1990 By Wes Jackson -

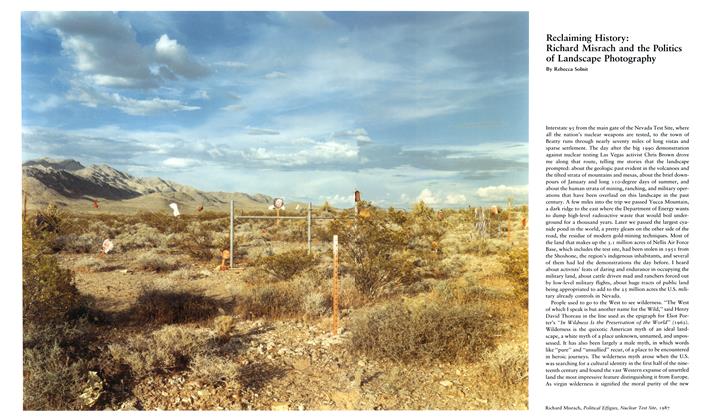

Reclaiming History: Richard Misrach And The Politics Of Landscape Photography

Late Summer 1990 By Rebecca Solnit