Through the Looking Glass, Darkly

Rosetta Brooks

The era of mass consumerism in Britain was born after the Second World War, in a heady atmosphere in which optimism was combined with a desire to start anew and a yearning for order after the chaos of the war years. At that time England took her lead from her prodigal son, America, acknowledging, for perhaps the first time in her history, that her preeminence as an economic and political force had come to an end. The British found themselves in a new era, a whole new ball game with different ground rules, in which England was just one country among many who were trying to start afresh after the devastation of the war.

Postwar consumerism reached its height in Britain in the ’60s, when attempts to americanize the culture achieved their greatest strength. Nowhere were these efforts more apparent than in the idealized images, depicting the better life that a consumerist Britain would supposedly partake in, that saturated the media in that era. Mass culture, mass communications, mass production: the very terms suggest quantity, the mainstream majority, sameness rather than difference, the undifferentiated crowd. All of these qualities, though, were antithetical to traditional British culture, which had always been characterized by its emphasis on individualism, even eccentricity. If, in the 1930s, the mass media in Britain and elsewhere had often represented the crowd as a frightening force, in the ’60s the crowd was shown as unified, harmonious—Coca Cola’s giant singing family.

Yet alongside this idyllic picture of the benefits of sameness was the image of the corporation. The belief in technological progress that provided an important underpinning for the ideology of consumerism was embodied publicly in monumental images of corporate power. The huge screens and giant billboards that changed the landscape of Britain so dramatically in those years seemed to suggest that the future would be, if nothing else, big—outsized, to match the scale of the corporate agents of the new consumerism.

Some of the most powerful and effective representations of the utopianism of the era were the logos devised by the major movie companies. Although it originated earlier, MGM’s roaring lion took on a new symbolic force in Britain after the war. It could be seen as a metaphor for the effects of film itself: the medium roars, and our senses are saturated. More than a corporate stamp of identity, the MGM logo became a powerful symbol of media imperialism. Postwar Britain, with its widespread desire for strong leadership and a sense of direction, freely acceded to the media’s claims to sovereignty as symbolized by MGM’s roaring lion.

But by the 1970s it became apparent that the unifying culture machine which had seemed so powerful and attractive in the ’60s had begun to sputter badly, as economic depression in England exposed the falseness of these imported images of innocence and unity. Cutbacks in education and jobs, in housing and health care, disrupted the mainstream consensus in England—if, indeed, one had ever really existed. The breakdown of the consumer culture that had been the hallmark of the ’60s now reinforced the feeling that British culture had always been— and remained still—a culture of ghettoes, of islands within the larger island. These autonomous and mutually exclusive entities had no desire to be absorbed into the kind of mainstream identity that is central to American culture.

If anything, the transgression of any mainstream has long been characteristic of English culture, which has always been obsessively, even masochistically, eager to explore the margins of life, more interested in the detail than the whole. The spectacular openness that was both the promise and the demand of consumer culture contradicted the British passion for assembling a psychological map out of cultural fragments, for seeing the world not as a simple, homogeneous whole but as a complex series of close-up views, made from different perspectives. The sense of openness and innocent optimism that had accompanied the consumer paradises of the ’60s had denied the British their accustomed opportunity of turning to the marginal underworld and the subversive underside of culture for social meaning, and had prevented them from exploring the dark myths that lurked beneath the superficial gloss of appearances.

By the 1970s, media images had begun to emphasize the disjunctive elements of culture, the pieces that didn’t quite fit, rather than the cloying, all-embracing unity of consumer culture. In opposition to the happy-face images purveyed by the mass-culture machinery, streetwise subcults now proclaimed a threatening shadow-world in which subversion and consumerism were linked. Skinheads, poseurs, and punks all served as evidence of the growing sense of alienation many felt from the illusions of homogeneity offered by mainstream culture.

In fashion terms, punk clothing, with its torn T shirts and tattered tights, its red eye-makeup and black lip gloss, provided a graphic representation of youth’s estrangement from conventional images of sexual allure. With typically British, tonguein-cheek cynicism, punk clothing appropriated the most socially transgressive garments of pornography and deviance, taking them out of the secret recesses of the psychosexual closet and parading them through the streets. Lifted from the contexts of the nursery, the deviant’s closet, and the sex shop, these clothes—with their safety pins and suspender belts, leather and vinyl wear—joyfully proclaimed a disruptive violation of traditional fashion symbolism. Like elements in a collage, the fashion images that were combined in punk style produced a conflict between the disparate social codes they represented; wearing these clothes became a strategy for breaking through social boundaries.

As more and more images with deliberately ambiguous social meaning have appeared throughout the ’80s, attempts to awaken a sense of cultural centrism in England seem finally to have been laid to rest. The optimistic, “brand new” world of consumerism opened up by the media in the ’60s has now been left behind. Once again England has embraced the richness of cultural fragmentation, rather than the indifference of cultural unity. Consumerism’s open panopticon had become a Piranesian prison for a culture whose strength of vision has always been maintained by its askew, off-center quality. Splintered by the economic rigors of recession, the British sensibility has found a new unity in variety and difference rather than sameness and uniformity.

Britain in the 1980s has become a society in which the idea of the mainstream has given way to a potentially infinite number of social spaces in which small groups, and even individuals, can act out their interests in collective isolation. In doing so, British society is following the model not only of immigrant groups, forced by legal and social constraints into physical and cultural ghettos, but also of the art world, which in modern times has always been relegated to the periphery of society. By remaining outside of accepted class hierarchies, artists have gained a measure of freedom, but by the same token they have been shunted into a marginal cultural role, unknown outside their own community except as fictionalized mass-media celebrities.

Perhaps in response to this societal breakup, many British photographers and other artists have dealt with issues of identity and community in their work. John Hilliard, for example, frequently butts together positive and negative versions of the same picture in his large photoworks, setting up tense pictorial equations that suggest questions of mirroring and image replication.

But in these twinned constructions Hilliard often uses images of non-Western people, thereby extending their implications to questions of personal and social identity, of Self and Other, as embodied in the mirror worlds of disparate cultures.

Susan Trangmar and Yve Lomax address similar questions of identity and representation in their work. In Trangmar’s series Untitled Landscapes, a mysterious figure appears in various typically British settings—in front of a church, say, or outside a factory. But in each case the figure is only an observer, not involved in the scene in other ways; she (and by extension everyone) has become a kind of tourist within her own culture. For their part, Lomax’s multipaneled photoworks, made up of disparate images juxtaposed into rebuslike visual constructions, suggest the possibility of discovering other sorts of meaning by placing images together. In the end, though, the pictures remain elusive, fragmented, suggestive rather than definite.

Although social fragmentation of this sort seems especially prevalent in British culture, it is by no means limited to it. Beneath the tissue of uniformity provided by electronic media and information technology, cultures around the world are breaking up into collections of parallel but diverse social groups based not only on such familiar categories as class and race, but also on common interests or desires—even on shared tastes in fashion or art. Increasingly throughout the world there no longer seems to be an all-encompassing, mainstream culture. Instead there is a growing sense of otherworldliness to our world. And it is just such a sense, of occupying an other-world reminiscent of the distorting-mirror world of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass, that has invariably exerted a fascination over the British imagination.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Romances Of Decay, Elegies For The Future

Winter 1988 By David Mellor -

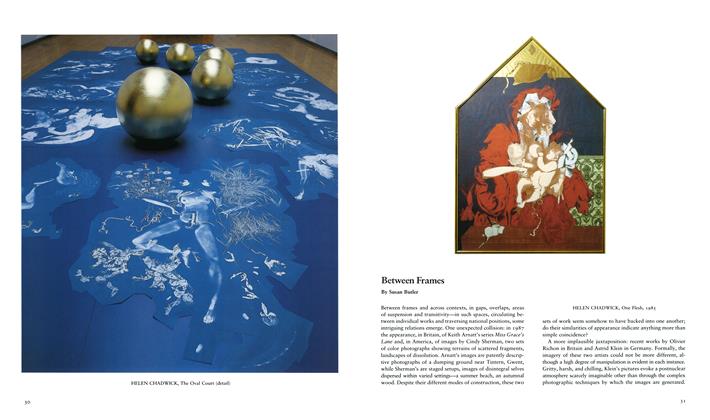

Between Frames

Winter 1988 By Susan Butler -

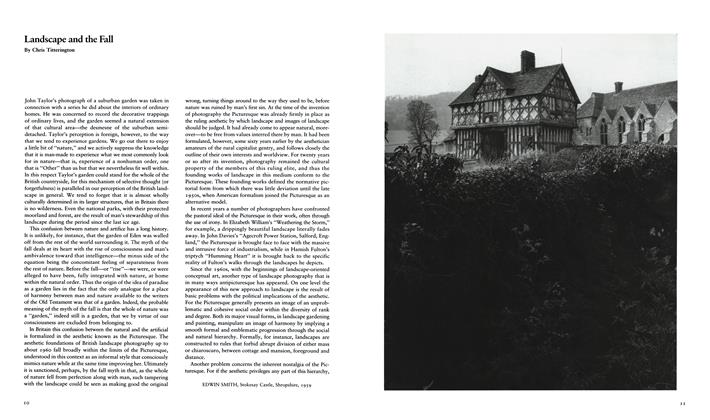

Landscape And The Fall

Winter 1988 By Chris Titterington -

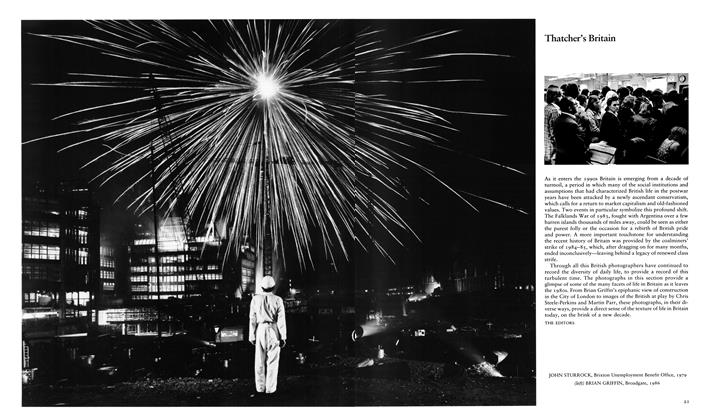

Thatcher’s Britain

Winter 1988 By The Editors -

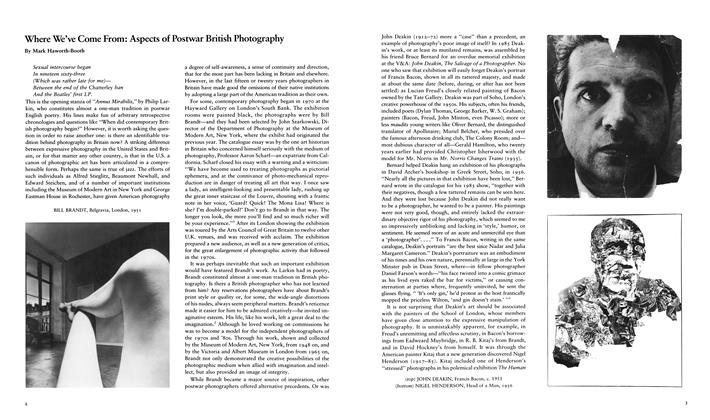

Where We’ve Come From: Aspects Of Postwar British Photography

Winter 1988 By Mark Haworth-Booth -

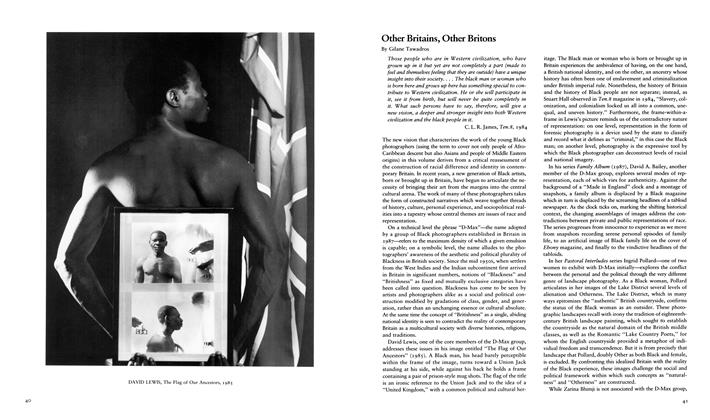

Other Britains, Other Britons

Winter 1988 By Gilane Tawadros