A Multiple Legacy

A Multiple Legacy

Creating the Space

Summer 1984 Drid Williams, Eugene Richards, Edward Ranney, Paul Caponigro, Robert Mahon, Abe Frajndlich, Peter Laytin, Haven O’MoreA MULTIPLE LEGACY

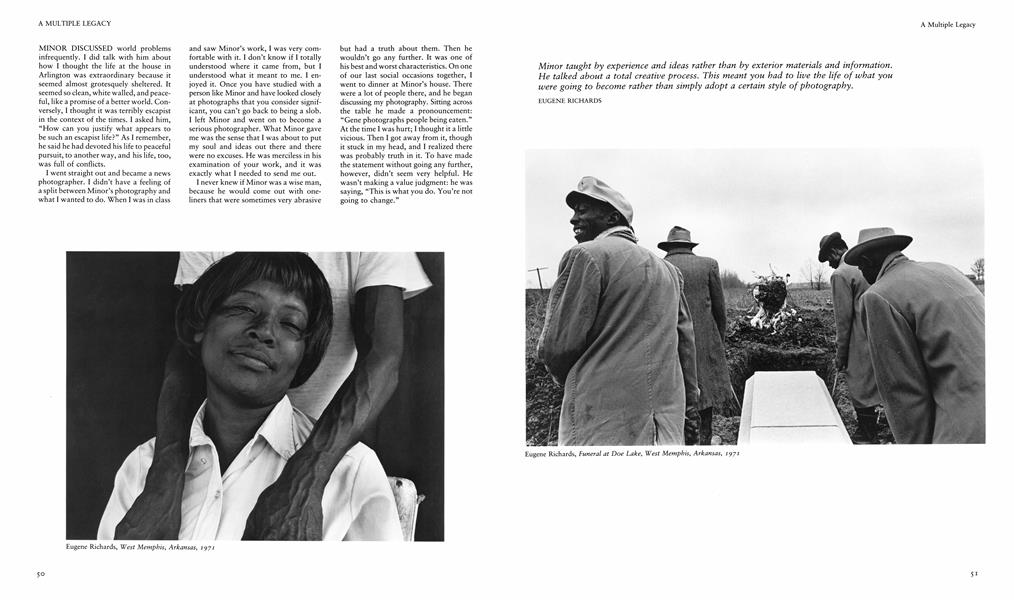

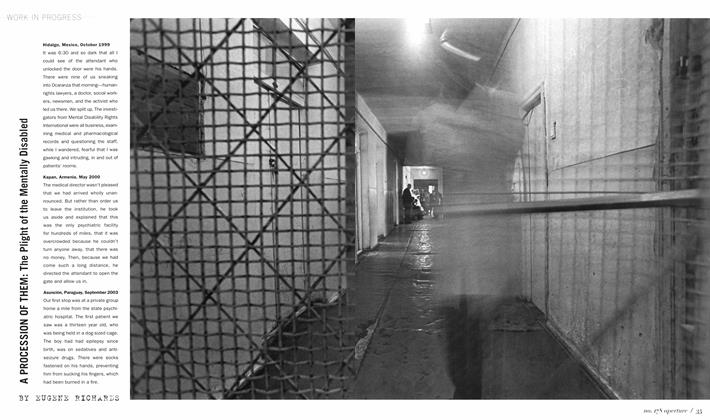

MINOR DISCUSSED world problems infrequently. I did talk with him about how I thought the life at the house in Arlington was extraordinary because it seemed almost grotesquely sheltered. It seemed so clean, white walled, and peaceful, like a promise of a better world. Conversely, I thought it was terribly escapist in the context of the times. I asked him, “How can you justify what appears to be such an escapist life?” As I remember, he said he had devoted his life to peaceful pursuit, to another way, and his life, too, was full of conflicts.

I went straight out and became a news photographer. I didn’t have a feeling of a split between Minor’s photography and what I wanted to do. When I was in class and saw Minor’s work, I was very comfortable with it. I don’t know if I totally understood where it came from, but I understood what it meant to me. I enjoyed it. Once you have studied with a person like Minor and have looked closely at photographs that you consider significant, you can’t go back to being a slob. I left Minor and went on to become a serious photographer. What Minor gave me was the sense that I was about to put my soul and ideas out there and there were no excuses. He was merciless in his examination of your work, and it was exactly what I needed to send me out.

I never knew if Minor was a wise man, because he would come out with oneliners that were sometimes very abrasive but had a truth about them. Then he wouldn’t go any further. It was one of his best and worst characteristics. On one of our last social occasions together, I went to dinner at Minor’s house. There were a lot of people there, and he began discussing my photography. Sitting across the table he made a pronouncement: “Gene photographs people being eaten.” At the time I was hurt; I thought it a little vicious. Then I got away from it, though it stuck in my head, and I realized there was probably truth in it. To have made the statement without going any further, however, didn’t seem very helpful. He wasn’t making a value judgment: he was saying, “This is what you do. You’re not going to change.”

Minor taught by experience and ideas rather than by exterior materials and information. He talked about a total creative process. This meant you had to live the life of what you were going to become rather than simply adopt a certain style of photography.

EUGENE RICHARDS

It is important to both study history and work within nature. Art brings together the work of nature and the work of man. The work of art does not stand by itself; it is a chunk of nature highly encrusted by man. To study art we need to study nature. The more alive we are, the more we tend to go back to what is written about the world and to the world itself; between these we reinforce our desires.

FREDERICK SOMMER, from “From the Birth of Art to Aesthetics,” 1982

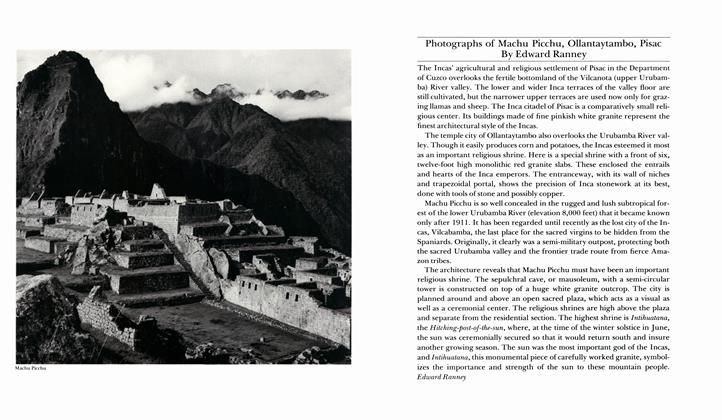

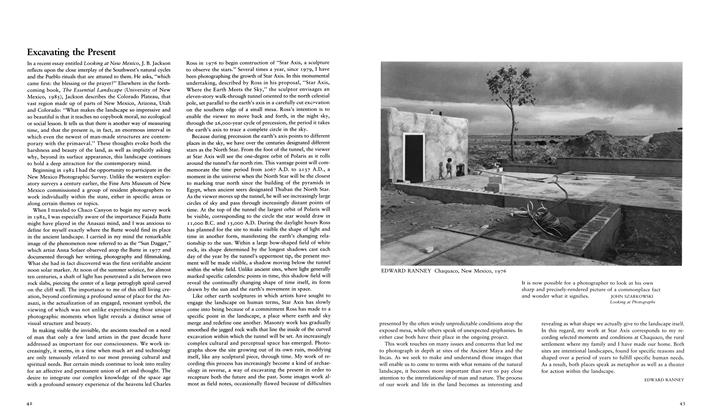

WITH ATTENTION to the now more fully published legacies of photographers such as Timothy O’Sullivan, Carleton Watkins, Eugène Atget, and Alfred Stieglitz, it has become ever more clear to me that those bodies of photographic work that have gained in meaning are those that originally found their vision in the external world. In doing so they have created their own inner world, while leaving us free to return to the external world with renewed respect and energy. How this might occur today varies, of course, with the personality and intent of each worker, as well as his point of entry both to his time and the history of the medium.

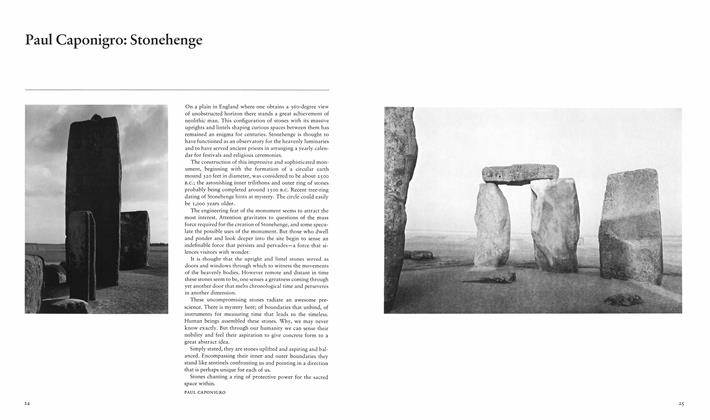

In the dislocated times of the midto late sixties, it was the vision and work of Edward Weston that sustained me in my early efforts in photography. At a time in our culture when it was imperative for sensibility to withhold consent from war and society, I was determined to work independently in photography, at a distance from living heroes in the medium. It was not until 1970, when some work had proved itself through time, that it became important to meet and share with Paul Caponigro an energy and awareness gained from photographing certain ancient sites and stones.

My own entry to the metaphysical landscape of ancient culture had initially been as a student living within the world of the Quechua Indians, near Cuzco, Peru. The concerns of my photographic work, while solitary, were often shared and encouraged by colleagues of Indian descent, as well as by artists, historians, and scientists. My commitment to photograph the remains of Inca stonework throughout the seventies was intimately related both to my feeling for the subject and to a need to establish a context of collective cultural meaning within which my work would have its place. Monuments of the Incas therefore became a multidisciplinary undertaking, one not strictly photographic in all its concerns, but nevertheless a work still deeply concerned with a photographic view of the world. In spite of the compromises and costs involved, the book form remains the most relevant and enduring context for photography in our culture. If it is an expression of vision and not self-promotion, the book is, in fact, the key format today in which a photographic statement can come closest to the integral role art once played in ancient culture.

The republication in 1969 of Robert Frank’s The Americans, the same year that saw Minor White’s Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations in print, was to me a significant moment for photography in American culture. Beyond its political and social concerns, Frank’s book implicitly asked what relevance a more formal language such as traditional landscape photography could have. By 1975, the year before Minor White’s death, the nominally “styleless” landscape documents known as “New Topographies” had brought attention to the inherently complex nature of photographic style and meaning, as well as to the continually narrowing sense of time and space of the contemporary American landscape. Embattled sensibility, wishing perhaps not to take refuge in art but rather to find an appropriate expression of life, however minimal, asked us to turn away from diminished icons, from form without meaning.

We are at a point in culture, as Lucy Lippard has written in Overlay, in which “. . . if art is for some people a substitute for religion, it is a pathetically inadequate one because of its rupture from social life and from the heterogeneous value systems that exist below the surface of a homogenized dominant culture.” Lippard also suggests, in discussing the implications of developments in environmental and performance art, that we are now seeing a reassertion of the social function of art that, as in primal or ancient cultures, affects people in a way substantially different from art that is “simply one more manipulable commodity in a market society where even ideas and the deepest expressions of human emotion are absorbed and controlled.” Minor White’s problematic legacy may have more to teach us now, as much for the inherent limitations of teaching only a self-referential kind of art, as for its searching quality, than it did during the last decades of his life.

Stone upon stone, and man, where was he? PABLO NERUDA, from Heights of Machu Picchu

EDWARD RANNEY

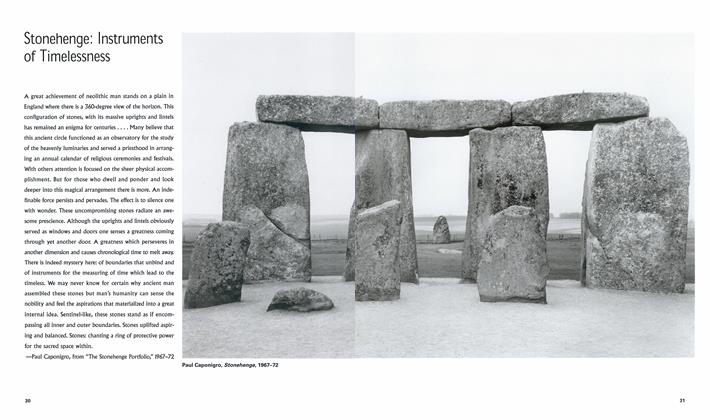

To the photographer temperamentally compelled to work inwardly his medium forces him to use the outward landscape to manifest by way of metaphor the inner reality. He has little more choice in this than the temperamentally compelled outward-going photographer has in his choice of tradition. Consequently the tradition of the Equivalent came into photography, if not Stieglitz first then someone else would have, and the contemporary Caponigros will sustain the tradition because by nature they can not do otherwise.

MINOR WHITE, Aperture, 1964

I MET MINOR WHITE in 1953 through Benjamin Chin, with whom I studied photography in San Francisco during my tour of duty with the U.S. Army. Benny had been a student of Ansel Adams’s and Minor White’s in the late forties at the California School of Fine Arts and had encouraged me to study with Minor. Benny thought my way of seeing was closely related to the West Coast tradition of photography, which was concerned with superb craft and form. He suggested I work with someone like Minor to develop another way of thinking about photography.

The evening I met Minor was the occasion of a farewell party for him given at Ansel Adams’s studio. He was leaving for a position at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York.

In the three years between that introduction and my first encounter with him as a student, I was discharged from the Army, spent some time in Boston, and returned to San Francisco, where I was exposed to individuals who were involved with photographing the grand natural landscape in all its power, as well as to people who were familiar with Minor’s ideas. After almost a year in California I grew dissatisfied with my pursuits—something was missing, though I couldn’t grasp exactly what it was. And then something happened: a retrospective of the paintings of Morris Graves at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opened my eyes. I was so struck by this work that I immediately realized what had been lacking in my work with the camera: that mystical quality, depth of insight, and penetration of nature manifest in Graves’s work is what I desired to see in my photography. My subconscious leaped at the recognition, and within two weeks I packed my bags and left for the East Coast.

To photograph not for what the subject is, but for what else it is.

From all I heard and what little I saw of Minor White’s work, it seemed that he came closest to what I felt about Morris Graves. Resolved to study with White one day, I wrote asking for a meeting and enclosed a portfolio of my work. In the fall of 1957 he invited me to come and live as an apprentice along with a few other students. I stayed on into December, helping with subscriptions to Aperture, which Minor was editing at the time, and assisting him in the darkroom. We all made field trips, separately and together, but most of the activity around the house at 72 North Union Street centered on looking at work and “reading” photographs, an activity that involved sitting in front of a photograph long enough for something to happen, to possibly break through to “what else the photograph is.”

The atmosphere at Minor’s place was quite beautiful. A spirit of cooperation mingled with good music, creating an almost dizzying kind of “special perfume” that we all inhaled. I felt that Minor carried the beauty of craft from the West and placed it on his walls in Rochester. In the sparsity and simplicity of the house a sense of Zen was achieved. We were encouraged to read Eugen Herrigel’s Zen in the Art of Archery and Boleslavsky’s Acting: The First Six Lessons. We were encouraged to meditate. Minor was reading P. D. Ouspensky’s In Search of the Miraculous at the time. All of this was certainly interesting, but I was far more intrigued with Minor’s work, both the photographs he was then making and work he’d done in the period prior to his move east.

I was taken by the fact that he could put on a piece of photographic paper a certain kind of imagery that did what he sought to do: to photograph for what else the subject is. In a way, he laid himself bare through his images. There was a good lesson to be had in his use of the “Sequence,” which he called “a cinema of stills.” By arranging a dozen or more photographs in a specific sequence (obviously a meaning was intended), he aimed at borrowing elements from each of the photographs and lending each of the images in the sequence new ideas and possible interpretations. A kind of story telling emerged. The sequences could be read in as many ways as there were students to look at them, but on occasion Minor would indicate that a few students had understood, in spirit or feeling, the theme he had intended.

Minor was indicating a way to approach the seeing of images. A kernel of the teaching was to break away from the associative, a very good device for opening one to other possibilities, but the device could also lead to oversymbolizing. This also carried over into the actual photographing: either Minor expected the student to arrive somewhere specific in the “reading” of images, or possibly he was experimenting to see where it all might lead. A lot of experimenting was in process. He would put you in a room alone with a few photographs and give you the task of relating your experience to the images. Sustained concentration was not always that easy, though; meaning did not always congeal from the complexity of the stuff in that photographic space mounted on a board or pinned to a wall. An insistence on finding meaning could hinder the possibility of simple seeing and intuitive understanding.

I traveled cross country with Minor in 1959, camping and photographing with him and assisting with his workshops in Portland, Oregon, and in San Francisco. The students loved and revered him, but a major complaint persisted among the more skeptical: why did they have to see things, and especially faces, in the photographs put up for the purpose of “reading” ? It annoyed some, intrigued others. But most of his students loved him for his generosity, energy, and caring. He had the respect of many simply because his dedication to the medium always shone forth; he worked seemingly without end.

We often heard about Stieglitz and the concept of the Equivalent from Minor. In all the time I was with Minor I never really understood what he was saying about Equivalence. Most of his students were trying desperately to make an equivalent, an achievement that marked the graduation from mere photographing to “real” photography. It seemed the idea of equivalence reflected the simple recognition of the unity of all things, the recognition of great principles operating in many things on many levels. Artists and poets of all mediums and from all times have had this awareness of linking principles and have attempted to make this awareness a primary tool for creation. Zen masters of painting seldom act until personal motivation is supplanted by the greater forces and combine with their being to create an act that includes the whole. They strive to become a part of a greater action. Self-expression is not enough for the Zen master. Imitation without understanding serves only to delay contact with the universals.

Minor was attracted to this idea of Zen and, I feel, took hold of it intellectually as most of us are prone to do. Making the transition to the actuality, however, requires a great leap. Without the depth of one’s total being, the great ideas we talked about could only be sensed. I believe that Minor strove to make equivalents as he understood equivalence, from the inspiration of Stieglitz. Stieglitz saw power in those things that he chose to photograph, and frequently managed to demonstrate that power in the image or, at least, provided a suggestion of that power. Recognition of the flow of power was the link between Stieglitz and his subjects. I feel that Minor interrupted the flow with too much personal concern. Consequently, Minor’s energy was dispersed into the ideas about equivalence and too often worked toward a formula that he hoped would eventually get him to the desired place. His early work was intuitive and full of aspiration; certainly, Minor’s images are very poetic and beautiful and often psychologically potent, but an inner thrashing and laboring is also evident. Minor did well in catching reflections of himself in his images, but I never felt that they carried that extra measure of power so evident in the work of Stieglitz.

We were all enamored of the atmosphere created by the person, and it was without question one of beauty and honest work, but I seldom felt that the overall situation allowed for clarity. There were too many delicious garden paths down which to be led. Too many attractive ideas. The multitude of methods put forth—Gurdjieff dances, “six lessons in acting,” hypnosis, Zen teachings—suggested that Minor was basically insecure about his stance in photography or, perhaps, in his life. The point may have been to try and increase one’s awareness through exercises, a most desirable state not so easily attained. Minor sought to make photography conscious, as he understood the Gurdjieffian meaning of the word. He was writing a manual on the matter while in Arlington, Massachusetts. Always the latest work on the spiritual quest, such as the escapades of Carlos Castaneda and Don Juan, would be taken up by Minor and incorporated into his teaching of photography. One method fully understood should have served. Many methods reshaped and partially understood was vague and nebulous, not unlike attending a séance. It left things cosmically cloudy. In his wellmeaning attempts to raise the level of photography (and photographs), Minor overembellished the process and failed to put photography in its right place.

I recall once meeting Paul Strand, who of course had known Stieglitz. I asked Strand what he understood by the idea of the Equivalent. He related to me a story of visiting Stieglitz: as soon as he got off the elevator of the building of “291” and before he rounded the corner to the gallery, Stieglitz would begin talking at him. I gathered from this story that Stieglitz was fond of holding forth. Regarding the Equivalent, Strand said, “I always have felt that photographing was a much simpler act than that.” I understood Strand to mean that a simple state of knowing and doing too often became confused or interrupted by a complicated idea.

My conclusion was that the simplicity and directness of the act could put one in touch with a process that might result in an Equivalent. I see it as holding a state of pure and deep recognition. You must be aware of a good state and use it, rather than think that an exercise before clicking the shutter is going to do something for you. Minor’s early photographs, I feel, were charged with love of work and with aspiration. He sensed something marvelous with which he desired greater contact.

In the years that I knew him, Minor attempted to formulate a method and teach creativity. In my opinion, this method was not in accordance with the essentials of the creative process. If one has engaged photography fully and with understanding and direction, it is enough in itself and offers depth of experience. Correct orientation to the self and one’s materials holds the key to a greater action. In my experience and in communicating with others about their experience, silence is one of the great traditions of teaching spirit. Apprentices are asked to sweep, observe, serve, and be silent in order to eventually acquire the greater action. Time and specifics do not burden or condition the atmosphere of such a situation.

There was something admirable and infectious about Minor’s exuberance and sense of adventure, something of a childlike aspiration. He was also a kitten at times, bouncing off walls and leaping in the air only to be surprised at where he had landed. There was also something quixotic in his activities, noble in purpose, but misdirected.

Obviously I have brought to the surface some long-standing questions, not about Minor but about the meaning of engaging in a craft for more than producing objects. I am grateful to Minor for so generously providing the abundance of positive elements and the sheer love and energy of working with photography. I am equally grateful to Minor for providing me with contradictions and contrasts regarding an approach to the way of the spirit. Minor was one of the most human of individuals, possessed of the failings, sufferings, and potentials we all carry. In certain areas he stood out like a Santa Claus for photographers, one of his greatest gifts being Aperture magazine, which helped the established and the young photographers to pursue camerawork as a fine art. It gave warmth to that cool world of anonymity and unacceptance experienced by the few pioneers of the medium. His loving care was exhibited by his insistence that the images of these fine artists be treated with respect and that the inherent beauty of their craft be evident through fine reproduction. The periodical was a pace setter and traveled a long distance from the very ordinary reproductions offered by other publications. With Aperture, Minor again demonstrated tireless effort and devotion.

PAUL CAPONIGRO

But if painting and sculpture do not communicate they induce an attitude of communion and contemplation. They offer to many an equivalent of what is regarded as part of religious life: a sincere and humble submission to a spiritual object, an experience which is not given automatically, but requires preparation and purity of spirit.

MEYER SCHAPIRO

I FIRST MET MINOR in 1959, and for about five years we engaged in informal talks concerning photography and vision. What he gave me was a way of looking at things rather than a way of working—an incentive to put down in pictorial form that thing that I loved. The principles of Minor’s philosophy, which combined the meditative approach with a high degree of disciplined craftsmanship, struck a responsive chord in me. Through him I gained a love and respect for camerawork, for the landscape, and for photography’s way of seeing. However, I knew from the start I had to find my own vision.

I have striven for a fuller, more realized image, a sense of mystery, a presence, and a kind of spirituality. I want my images to be tapestries, where the entire surface of the print has a life force full of revelation, lucidity, activity, and plenitude—a visual/emotional completeness.

ROBERT BOURDEAU

Upon confronting a difficult or puzzling photograph, an individual must decide whether the artist is being unecessarily obscure or the viewer, himself, is being unduly obtuse. We should be cautious about resolving all such questions in our favor . . .

HENRY HOLMES SMITH

octave for minor

stroke by stroke the calligrapher scribed the void

from that stylus quietness flowed a thousand miles

this tabula rasa mind was printed with his letters

his words became the constituents of our intellect

as his testament has been written in a pupil’s eye

so it is written His finger wrote upon this ground

inside this four dimensioned mind his stylus moves

beyond his death his stela stands on living stones

WILLIAM SMITH

Though leaves are many, the root is one; Through all the lying days of my youth I swayed my leaves and flowers in the sun Now I may wither into the truth.

W. B. YEATS, “The Coming of Wisdom with Time”

Only a small crash in the kitchen, but enough to shatter my calm and a bowl. One careless glance caught the pieces—white porcelain still quivering on the floor—a rice bowl, pleasant in subtle curve, from Japan, delicate to balance, was no more. He who dropped it fingered the pieces. He was silent and, I suppose, sad. I turned back to preceding thoughts. Then he was jubilant. One fragment, he exclaimed, “has a form. ” And truly he pointed to one that was haunting to see....

And since I make photographs it seemed natural to transmute yet again and make a photograph of it; to train my camera on the splinter seemed obviously the next step. But a thought stopped me. What is the status of a photograph of an object that has just found its own form? A copy? Or a photograph that in turn would find a form peculiar to itself?

There wasn’t time to think through such questions in the chain reaction of thoughts that followed the explosion. In the "fallout, ” however, I found a name for some of my own photographs. I always photograph found objects; excepting portraits, all of my photographs are of found objects. And now, thinking of the best of them, I hear little crashes tinkling back twenty years, for the best of them have always been photographs that found themselves....

MINOR WHITE, “Found Photographs,” from “Memorable Fancies,” 1957

Once, Minor called and woke me up at dawn to say that he had just got out of hospital after a heart attack. It so upset me I threw the I Ching for him, as we had done many times for each other. The hexagram that came up was The Wanderer. When you delve into that form of mentality you get more than an image. It is a highly sophisticated way of using your mind, which ancient people knew about. There is no chance involved at all. It is like the mystique of the Found Object. There was no chance because who found it anyway? Someone RE-COGNIZED it.

WALTER CHAPPELL

ch'i: vapor, breath, air, manner, influence, weather Ch'i: Breath of Heaven, Spirit, Vital Force

EDITOR’S NOTE: The vision oí The I Ching or Book of Changes was a discipline that Minor White actively embraced. A project he conceived but never completed was to photograph images equivalent to the sixty-four hexagrams of the book. Robert Mahon has applied the book to an existing negative. A multiple portrait surfaces. Its revelations are fragments that encourage us to rearrange our sense of the complete image. It becomes a metaphor close to the diverse legacy of Minor himself and the multiple faces of his own identity.

FROM JOHN CAGE I learned about the ancient Chinese oracle, The I Ching or Book of Changes, and how it is related to chance. Using the book’s sixty-four hexagrams, I applied the principle of chance operations to steps in the photographic process by considering the components that contribute to a photograph: angle of view, composition, and various aesthetic factors on the one hand, and shutter speed, development time, and different technical matters on the other. The two-hundred-and-sixteen-image portrait of John Cage that resulted was very different from any portrait I might have made according to a preconceived aesthetic view. The process taught me that chance in conjunction with photography is a way to free my visual perception from habit. The work is experimental; it becomes a way to discover something I had never seen before. I committed myself to this way of working so that personal biases or prejudices would not limit the possibilities and I would be allowed unimagined images, photographs made remarkable precisely because they had not been previously envisioned.

In 19821 made a group of photographs from inherited negatives. Using these procedures I made something new from old materials. Bathers is such an example. The subject is a familiar one: a young couple sitting on a beach. The subtle details in this image interested me: the sexuality of the woman; her obvious infatuation with the man; his probable indifference; the language of their hands, legs, and eyes; as well as the many vaguely recognizable objects and figures in the background. The negative was telling a story about a person in my family, and I wanted to examine it more closely.

The original image is never seen in its entirety since each new photograph is a fragment of the whole. The eye scans the fragments and the mind attempts to reconstruct the scene. A depth of understanding that would be unattainable in a single view derives from the highlighting, obscuring, and concentration on different parts. A complexity of characters, place, and narrative is revealed that might have been overlooked in a simple snapshot.

I seek to understand the moment that has been captured by the camera. I explore the potential of the negative and observe its limitless variety. This process is comparable to a law of the physical world: a finite line can be divided into an infinite number of segments. Knowledge of the line increases with the quantity of measured parts, but the knowledge can never be complete or absolute. The possibilities are endless.

ROBERT MAHON

I WAS TWENTY-FOUR when I attended [Minor’s] Cleveland workshop. ... I had just begun to take photographs. . . . I . . . arrived at the first day’s workshop twenty minutes late. A slide was on the screen. About fifty people were on the floor. The room was dark and filled with Minor’s low, almost chanting, voice.

The more I listened, the more intrigued I became. . . . [The] teacher in him . . . captured my imagination. He opened up the multiple levels of a color slide of two footprints in wet sand by telling us: “In the life of every man, there comes a point when he walks on water.”

Minor used ritual to keep himself and his students alert to life’s possibilities. His insistence on ritual stemmed from his commitment to Gurdjieff’s philosophy. Part of his philosophy, too, was his conviction that photography was not a parlor game or a weekend activity, but . . . was as essential to our lives as breathing.

Minor constantly put us through exercises to enlarge our sensitivity to photographs. He was interested in the reactions a print could engender in the viewer. We were urged to tune our bodies to the making of an image, to suspend the whole rational process. Minor also had a knack for leading us into deeper waters. “Just get into the confusion,” he would say. “Just be confused. Quit trying to be clear. Quit putting such a premium on clarity.”

ABE FRAJNDLICH, from Lives I’ve Never Lived:

A Portrait of Minor White

I LIVED AT MINOR’S house in Arlington in 1971 and 1972. I saw Minor play and live his roles as a photographer, photography teacher, department chairman, workshop leader, student/teacher of Gurdjieff, counselor, and friend. Our bond of friendship grew.

During the months before his illness, while I was living with the woman who is now my wife, Minor would call on the phone and ask if we wouldn’t mind his coming over for a visit. Of course we would scurry about cleaning things up, discussing how out of character it was for Minor to drop in.

Minor returned to the hospital for the last time after months of involvement with lawyers, legal problems, and doctors. Our main concern was to have Minor as free of tubes and drugs as possible, according to his wishes. Mrs. D., a very close friend of Minor’s, and I were working closely with the doctors and nurses. One evening during dinner, I remember calling the hospital to check on the situation and was told that Minor had been repeating my name and asking that I be there with him. I immediately returned and began a twenty-hour experience that was a lifetime in itself. Minor would drift in and out of sleep and describe what he saw, and there in his darkened room, my hand in his, I began to see the same images. We were able to talk about them. At times when his fear or anxiety seemed to swell, I could help him return to the small wooden rowboat we were in as we drifted from one shore to another. Minor’s description of an intense white light became visible for me. I knew I was hallucinating. It was the early hours of the morning, I was exhausted from weeks of emotional pressure, yet those hallucinations were clear. I was on this voyage. There were interruptions, nurses whispering, snapping me from the comfort of the boat. But always I would return.

When we finally arrived at the other shore, it was time to say good-bye. I felt I had to make a choice. I could step off the boat and enter this new realm or return. Minor was gone— although still hours away from his last breath. Did we say our good-bye in a hospital room or on that shore?

For many hours I sat with him after that good-bye. Minor’s last words were “higher, higher.” Did Minor mean, if we must put meaning to them, that his spirit was reaching new heights, or that we should elevate our goals, or that he was being lifted from this bodily plane to an ethereal one, or might he have been requesting to be propped up higher in his bed so as to make his breathing easier? I believe those words, and what already has been done with them, encapsulate the myth around Minor. It is the ambiguity that is the key.

Minor as a teacher created a situation that at times he controlled, and at times he didn’t. The myth preceded him, and maybe his fault is that he did nothing to prevent it. He created an atmosphere for constantly questioning ideas or responses. It is we who must judge how we question the decision process in ourselves.

PETER LAYTIN

Creating the Space

DRID WILLIAMS

MINOR CAME FROM MINNESOTA. That was significant because of the sense of space he grew up with. Minnesota has forests, lakes, the Iron Range, and a feeling—like all of the plains states—of unbounded space. It is flat. Hot like the bottom of a frying pan in summer and cold like an icebox in winter. There are wild extremes: punishing hardship and delicate subtleties. Unlike the Pacific Northwest, which is dominated by the vertical dimensions of mountains and evergreens, a winter landscape in Minnesota is sparse, Zenlike; endless reaches of different white hues and subtle tans, grays, blues delicately accented with black. It is also a place that someone like Minor would want to get away from. This shows in his work. He had a sense of living in a world that has no limits; that he could travel, and that he could meet people with whom he could communicate. The very expanse of his native state gave him a sense of fewer limitations.

I met Minor in 1957 through Bill Smith, whom I had known since I was a thirteen-year-old in Oregon. I was deeply involved with modern dance in New York at the time and was invited to Rochester for a weekend to meet Minor. Minor’s home environment was simple and meaningful: a plain(s) sense of space with tree stumps, rocks, plants, and water was right there in the living room. A few hours after I arrived, Walter Chappell appeared. The whole afternoon and evening subsequently became dominated by my interaction with Walter. Minor remained the onlooker and made no judgments. The weekend culminated with a trip out to the William Gratwick farm.

Walter is one of the fastest photographers I have ever known. He has incredible speed and mastery that conceal technique and equipment. He didn’t say much, and most of the time I wasn’t aware I was being photographed. There came a point late in the afternoon when I entered the dining room and there were about one hundred fifty photographs of me laid out on a long table. I was a dancer. I had been a model. All the flags of my vanity were flying. Suddenly, I was face to face with all those “selves” of which I was not aware—all the images of all the “Drids”: everything from madonna to bitch, from crying child to serene hostess. At that moment (with Walter across the table and Minor and Bill beside me), I knew that I was facing something very important—and somebody who saw. It was not Minor at the time but Walter Chappell who wanted to do more photographs. I simply zeroed in on the feeling, and that is where Walt and I were for almost seventy-two hours. I think that I slept for about four hours. It was the kind of moment that is extremely rare.

Minor was an observer to all of this, and I am sure that he restrained Bill from breaking it all up. All the stops were pulled out, as on an organ, and I think that Walter must have made several hundred photographs. I knew later, but did not know then, that some of these involved the movements of Gurdjieff “first obligatories.” I could not have had a clearer message that I didn’t know who I was or what I was, but the important thing is that this was the kind of thing that could happen in the spaces Minor created. Spiritually, Walt was one of Minor’s teachers. I started the Gurdjieff work in 1959 through Walter, who thought I didn’t remember anything. But I did remember, not only about the interaction with Walter, but also that without Minor, one of whose greatnesses lay in the ability to create spaces where truly significant things could occur, nothing would have happened.

When you look at me—even now—you are looking at a symbol in Minor’s semiotic of that female quality that he spent most of his life trying to come to terms with. There had to be a female element, otherwise the creative process would not have been born, nor would it have matured. Sequence 17, which included his portrait of me in an important sequence because it is the only one, to my way of thinking, that makes sense out of his quest—his inner spaces, which are best understood, perhaps, in terms of the relation between anima and animus. There was no resolution to Sequence 17. Minor never misled his students into thinking that there was—God knows how many imitation Sequence 17s we’d have had to live with if he had!

I saw Minor five weeks before he died in Boston. I had just returned from Oxford, having seen him the previous autumn in London. He knew he was going to die. The resolution to Sequence 17 was never photographed. It occurred between us, sitting in another living room with the same sense of spaces that his homeplaces always had. He said, “Before I leave, Drid, I have to say that I have misunderstood ‘you’ all these years. I have done ‘you’ a disservice, because I always thought your love for me was erotic, which it never was, and I have never seen you until now, but you saw me, didn’t you?” When he comprehended agape and transcended er os, Sequence 17 was completed, by the span of his life.

To get to Minor, you have to try to understand the person who creates spaces. Otherwise, you will be inundated by people who will only tell you what happened to them in those spaces. This man was a creator of spaces with a powerful faith and a guiding hope that he would attract to the life-spaces he created the people, things, and ideas that he wanted to understand and by which he hoped to transform his life. Thus he tried to create spaces where koans could happen. I believe that this was crystallized in Rochester when he was deeply involved in trying to understand sequencing and the structures of equivalence. He was applying the apperceptions thus gained to his own life at the same time that he was applying them to photography. And it is all important to note, I think, that meeting Minor was never to feel that his spaces were strange, or outré. Minor was real in the common, ordinary sense of that term.

Minor’s spaces—outer or inner—were calm. He could talk to many people: consider the range of kinds of person who were in his space and who orbited around him. The space he created did not disregard those who did not understand the koans or the intensities of the kinds of inner transformation that I experienced. He honored the social climate of his time, which tended (and still tends) to encourage people to forget or ignore other dimensions. Yet he knew that (some)one has to create spaces in this commonality where deeper, more profound things can happen, because if this isn’t done, the commonality can become overpowering. Something is always happening to distract people from the deep quest—the long journey to one’s real home: if it isn’t the sheer pressure of mundanity, then it is the Crusades, or Vietnam, or the threat of World War III, or the plight of the poor, or something. All of that is mechanical. It simply goes on and on and on. The point is that the Minor Whites of this world, for some unknown reason, consider it a mission, really, to allow those who may be deeply involved in all of this to remember—so they create spaces where that kind of remembering can happen. It becomes a deeply felt moral obligation, especially if one is an artist of Minor’s caliber. How else can the statement be made? (And, by the way, it cannot be fabricated, although many try.)

I was attracted to cultural anthropology because, among other things, it deals with the “other” inside and outside one’s own society. It is very interesting to be the other in one’s own culture: it is both a condition and a psychological state where one possesses at least two maps of the human territory—not one. There is a vertical axis that has to do with levels of be-ing, and there is the horizontal axis of life’s progression. The meaning of Minor’s life lay on the vertical and not the horizontal axis of his being. Suppose that the conditions of pre-Renaissance art were maintained in our society, specifically the condition of anonymity, so that artists did not sign their work. How many contemporary artists would still make art, if doing so didn’t glorify their individuality and their name? The most profound understanding of Minor White, in my view, consists in the fact that he would have done what he did under any conditions. That, in my opinion, is the test.

Most of the notions about Western art, including photography, are constructed from the point of view of the spectator, which, in the end, is a relatively superficial, or at least incomplete, assessment. Most audiences know nothing about the creation of an artifact. An artist like Minor doesn’t think of creating artifacts or art. Spectators of Minor’s work (or his life) never comprehended that he worked like a horse day after day. They are usually ignorant of the discipline that the work entailed. Minor’s life is a monument to the values of the practice of art, not to the values of the current social institutions of art. Sometimes these are similar, but more often they are not coincidental.

We talked a lot about role playing and conscious role playing as against unconscious role playing in life, and the connections that this may or may not have with the notion of authentic human be-ing and about the lives that we haven’t lived and the lives that we have lived. But the kind of life that Minor lived that enabled him to produce the extraordinary legacy of his work—the sequences, the equivalents, and all—was not sensational: he didn’t use drugs, spend time in a psychiatric hospital, sleep with multitudes of people, or live la dolce vita, because if he had he couldn’t have practiced his art. He was a plain man, an educated man, and a very shy man, really. He got up, cooked his meals, typed, paid his bills, conversed with people, swept the floor, and spent hundreds of hours in the darkroom. He was what is known in Sufi disciplines as a good householder. You have to be able to manage your house before you can cope successfully with higher levels of spiritual understanding, because those levels don’t make anything easier. On the contrary, the traditional routes and paths to enlightenment are always through discipline, and the disciplines of ordinary life are the hardest of all because they are so common. Minor’s real life, like that of most great artists, would not make good copy for pulp magazines and sensational journalism, because his real life, like the phoenix, the hoopoe, or the king’s falcon, does not come to those who are so deeply immersed in “real life” that they are sleeping when “the other” happens.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A CREATOR, to be a maker in the true sense? First it means to align oneself: to hold oneself steady in the wind of life, and see where others merely notice or running, pass too fast to even notice. Next it means to wake up. To be awake means to taste the flavor of things all the way to the pulsebeat and on into the heart of things . . . then further. Again we can go to Minor White who early in his work had been “seized”: “Surfaces reveal inner states—cameras record surfaces. Confronted with the world of surfaces in nature, man, and photographs, I must somehow be a kind of microscope by which the underlying forces of Spirit are observed and extended to others.” (My italics.)

Surfaces (structures, as this might be better named) provide the key to man’s innermost being and are the most important link with the world itself as an extension of man. If anyone has ever wondered, Why photographs? White’s work will answer his question in an almost awesome way when it is “used” as it has been made to be. In short, photographs (some photographs when made by a master photographer like White who knows exactly what he is doing) X-ray the inner states of things and reveal to us the Why, Is-ness beneath appearances. “For it is in the most eminent degree the province of [real] knowledge, to contemplate the Why” (Aristotle, Posterior Analytics, I. 14. 79a23). We leave the merely What behind. We become the true camera; we survey man and the manifestations of Nature and ourselves and we see through our fleshly eye and with the Eye of Spirit, the most subtle Eye that is no eye. To see with no eye: this is truly the function of all art in relation to man— both as maker and viewer—and no human being remains locked in the prison of his flesh when he comprehends and participates. . . .

HAVEN O’MORE

Resemblance reproduces the formal aspects of objects but neglects their spirit; truth shows the spirit and the substance in like perfection. He who tries to transmit the spirit by means of the formal aspect and ends by merely obtaining the outward appearance will produce a dead thing.

CHING HAO

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

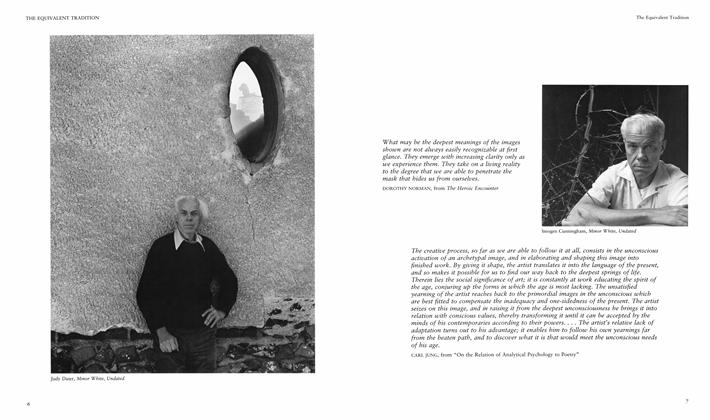

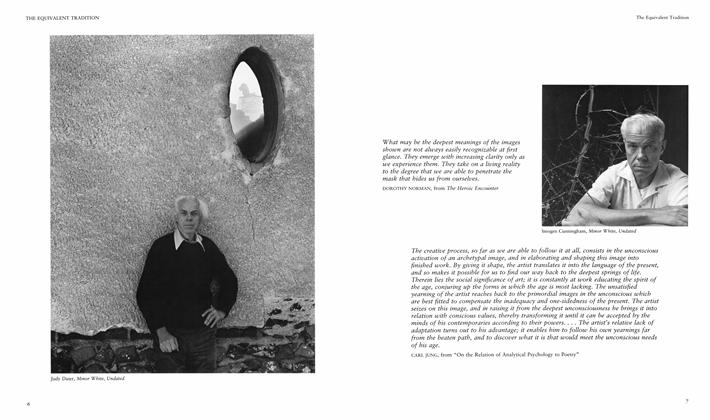

The Equivalent Tradition

The Equivalent TraditionThe Equivalent Tradition

Summer 1984 By Minor White, Walter Chappell, Frederick Sommer -

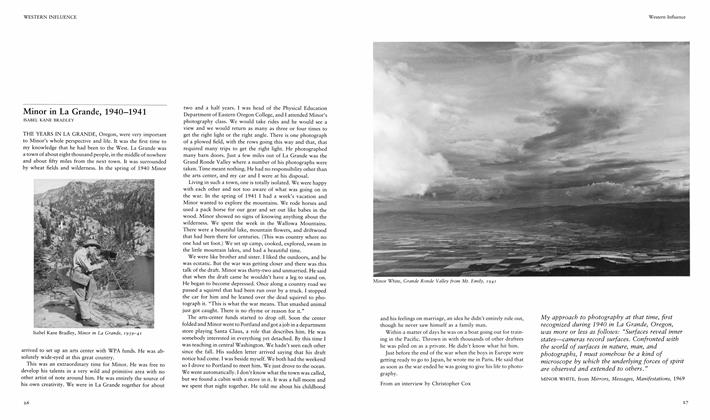

Western Influence

Western InfluenceWestern Influence

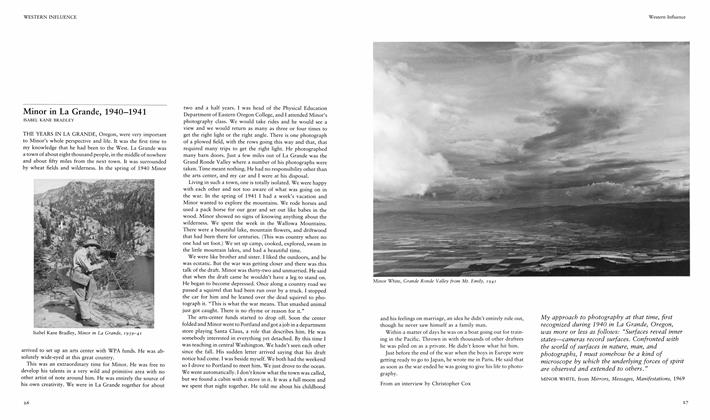

Summer 1984 By Isabel Kane Bradley, Ansel Adams, Barbara Morgan -

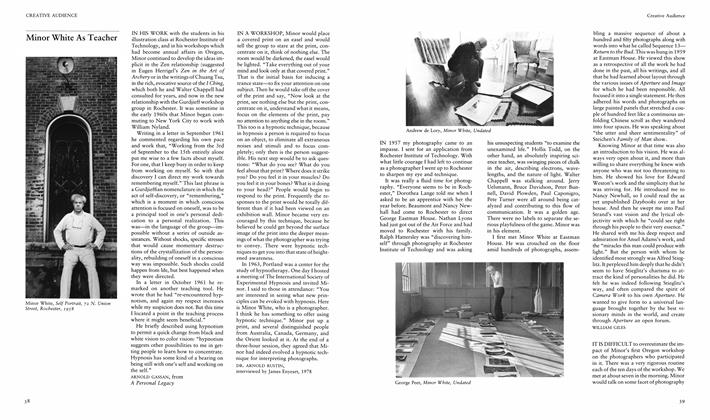

Creative Audience

Creative AudienceCreative Audience

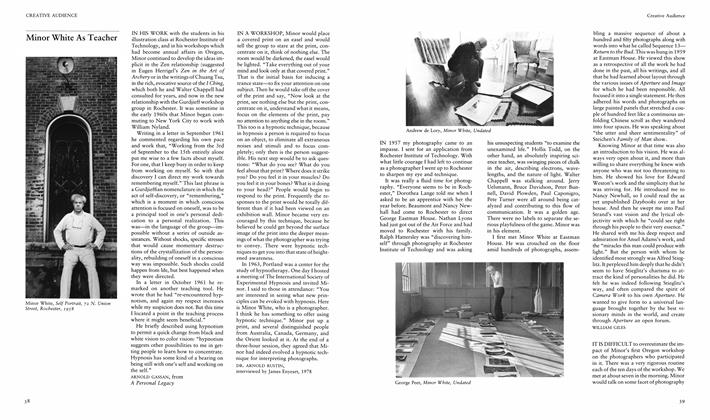

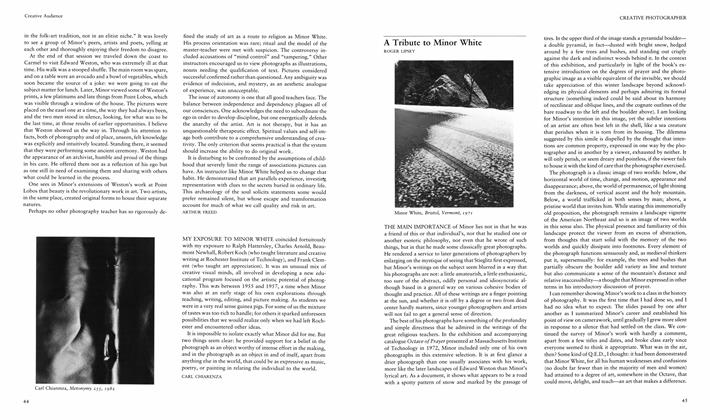

Summer 1984 By Arnold Gassan, William Giles, Gerald Robinson4 more ... -

Creative Photographer

Creative PhotographerCreative Photographer

Summer 1984 By Roger Lipsey, Robert Adams -

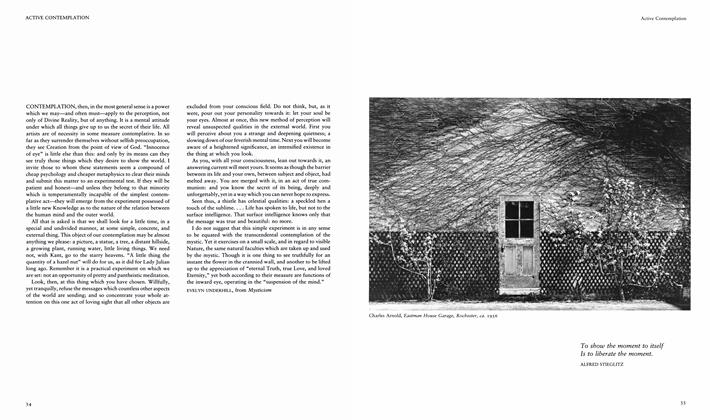

Active Contemplation

Active ContemplationActive Contemplation

Summer 1984 By Evelyn Underhill -

People And Ideas

People And Ideas"To Imply, And Then To Amplify"— Homage To Art Sinsabaugh, 1924— 1983

Summer 1984 By Jonathan Williams

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Edward Ranney

Eugene Richards

Haven O’More

More From This Issue

-

The Equivalent Tradition

The Equivalent TraditionThe Equivalent Tradition

Summer 1984 By Minor White, Walter Chappell, Frederick Sommer -

Western Influence

Western InfluenceWestern Influence

Summer 1984 By Isabel Kane Bradley, Ansel Adams, Barbara Morgan -

Creative Audience

Creative AudienceCreative Audience

Summer 1984 By Arnold Gassan, William Giles, Gerald Robinson4 more ...