Reviews

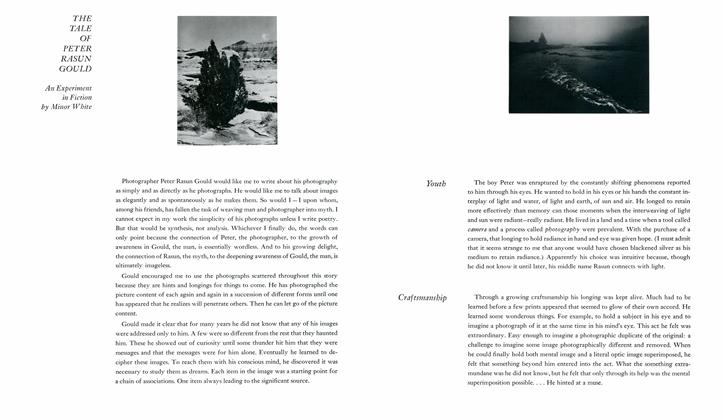

The Encounter Of Man And Nature: The Spiritual Crisis Of Modern Man

Summer 1970 Haven O’MoreThe Encounter of Man and Nature:

The Spiritual Crisis of Modern Man

by Seyyed Hossein Nasr, George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London, 1968, 151 pp. (incl. notes and index), 30s; Fernhill House Ltd, New York, 1969, $4.50.

To photographers looking for the reasons and origins of our present spiritual crisis the symptoms of which he photographs in strikes, riots, dissent, and pollution, Nasr's book presents origins and reasons. To photographers who have begun to doubt the power of photography to affect, much less prevent, war, starvation, or social inequalities Nasr offers solutions. Though hard reading, the book presents means within our reach of coping with the crisis.—Editor.

How does it stand between man and Nature?

Asking this question is the same as asking, “How does it stand with man in the last third of the 20th century?” For in essence there can be no division between man and Nature despite modern industrial man’s striving with what power and energy he has to prove otherwise.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr hints at this in the subtitle to his work, first delivered in the form of lectures under the sponsorship of the Rockefeller Foundation at the University of Chicago during May 1966. It should be added that this book is anything but “timely” dealing as it does with the aspects of things which are as the Upanishad has it, “Beyond past beyond future, without beginning or end . . . the same today and same tomorrow.”

Yes, how does it stand with man? The evidence, both internal and external, is too overwhelming for complete description. Deep reflection on man and his present state led Seyyed Hossein Nasr to write The Encounter of Man and Nature.

Dr. Nasr divides his book into four chapters: 1) The Problem; 2) The Intellectual and Historical Causes; 3) Some Metaphysical Principles Pertaining to Nature; and 4) Certain Applications to the Contemporary Situation.

Each chapter carefully defines and analyzes the issues from a point of view all the clearer because it sees above contingencies. In defining the problem Nasr speaks of modern man’s loss of the sense of the transparency of things, “of intimacy with nature as a cosmos that conveys to man a meaning that concerns him...The near disappearance of gnosis, as understood in its true sense as a unitive and illuminative knowledge, and its replacement by sentimental mysticism and the gradual neglect of apophatic and metaphysical theology in favour of a rational theology, are all effects of the same event that has taken place with the souls of men. The symbolic view of things is for the most part forgotten in the West and survives only among peoples of faraway regions, while the majority of modern men live in a de-sacralized world of phenomena whose only meaning is either their quantitative relationships expressed in mathematical formulae that satisfy the scientific mind, or their material usefulness for man considered as a two-legged animal with no destiny beyond his earthly existence.”

As Nasr ranges over the rationalistic and historical causes of our current problems, he appears to neglect nothing vital to the issue. One example of this must do, selected as it is from a richness of text and notes. “The theory of evolution did not provide an organic view for the physical sciences but provided men with a way of reducing the higher to the lower, a magical formula to apply everywhere in order to explain things without the need to have recourse to any higher principles or causes. It also went hand in hand with a prevalent historicism which is a parody of the Christian philosophy of history, but which nevertheless could only take place in the Christian world where the truth itself had become incarnated in time and history. A reaction is always against an existing affirmation and action.”

The third chapter, perhaps the heart of the discussion, defines metaphysics and applies metaphysical principles to the understanding of Nature. Here Nasr literally followed the Prophet’s Hadith, “Seek knowledge even in China.” Nasr writes:

“We have so far often mentioned metaphysics. It is now time to define what we mean by this all important form of knowledge, whose disappearance is most directly responsible for our modern predicament. Metaphysics, which in fact is one and should be named metaphvsic in the singular, is the science of the Real, or the origin and end of things, of the Absolute and, in its light, the relative. It is a science as strict and exact as mathematics and with the same clarity and certitude [we add more exact than mathematics, and with a clarity and certitude far exceeding anything glimpsed by mathematical means], but one which can only be attained through intellectual intuition [this is to say, direct seeing without the intervention of any sense or psychical function] and not simply through ratiocination. It thus differs from philosophy as it is usually understood. Rather, it is a theoria [a seeing] of reality whose realization means sanctity and spiritual perfection. ... It is only in its light [that of metaphysic] that man can distinguish between levels of reality and states of being and be able to see [our emphasis] each thing in its place in the total scheme of things.”

It should be obvious to anyone who thinks about it that metaphvsic defined in this way has nothing to do with philosophy or the metaphysics long, and incorrectly, considered a part of what goes by the name of philosophy in the modern world and squeezed with it by academicians into less than a parody of metaphysic. Metaphysical discussions by professional Western philosophers have become so sterile even the philosophers themselves have quit joking about the subject, a sure sign that it, not God, is dead. The joke if there is any is that such “metaphysics” was never alive.

Is there a way out of his predicament for modern man? We believe with Nasr that there is. This work differs from others because it does offer a solution; where other writers venture any solution at all it is often in the same facile terms, oversimplified to the point of near idiocy, which share the “reasonable” point of view responsible in the first place for the very problems the writer would propose solutions for. But as Nasr says in the last chapter, “Whether any suggestions of a spiritual and intellectual nature will be heard by a world which has turned its ears to the sound and fury of its own making and become deaf to all other voices remains to be seen. The attempt to think of this major problem and to provide an answer is nevertheless itself worth while, for to seek to discover the truth in any matter is the most constructive of all acts.”

Pilate asked, and still asks, “What is truth?” Whether the world survives depends on how we seek and understand the answer.

This book should be taken into the highest councils in every world government. Should, but probably will not be; the time is against it. And for good reason: if the ideas developed in The Encounter of Man and Nature were applied the modern world would be extinguished.

These ideas are not original with Nasr, only the expression is new. Nor are Aristotle’s or Plato’s or Proklos’ or Christ’s or, for that matter, any man’s ideas original with him. Far from it. Were the ideas expressed merely “original” with these persons they would have no value to anyone else. The only value of any idea derives from its reality, from its relation to the Real; and reality, if it is reality, is never reality in a time-bound individual but only as it is universal and timeless. With this these ideas achieve value for all men outside of time and place, the self-limiting constructs imprisoning the individual in his own ego.

“A true teacher is one who knows (and makes known) the New, by revitalizing the Old.” What other way than this, put so well by Confucius, is there?

Haven O'More

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

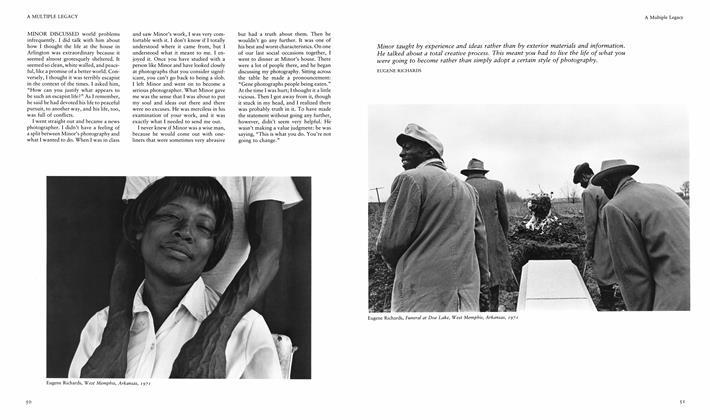

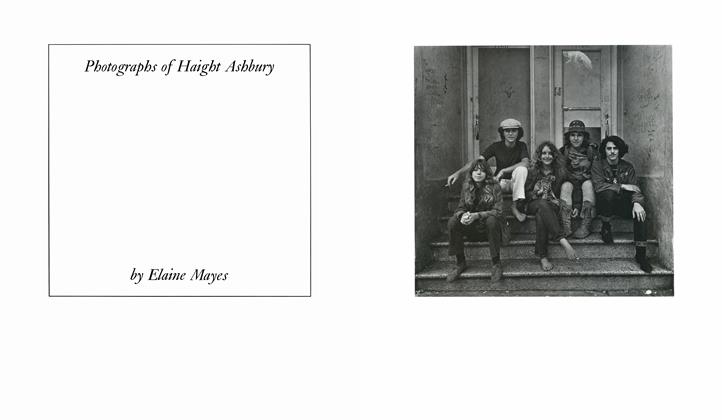

Photographs Of Haight Ashbury

Summer 1970 By Elaine Mayes, The Doors -

The Tale Of Peter Rasun Gould: An Experiment In Fiction

Summer 1970 By Minor White -

Pictures By Scott Hyde

Summer 1970 By Syl Labrot, Scott Hyde -

Summer 1970

Summer 1970 -

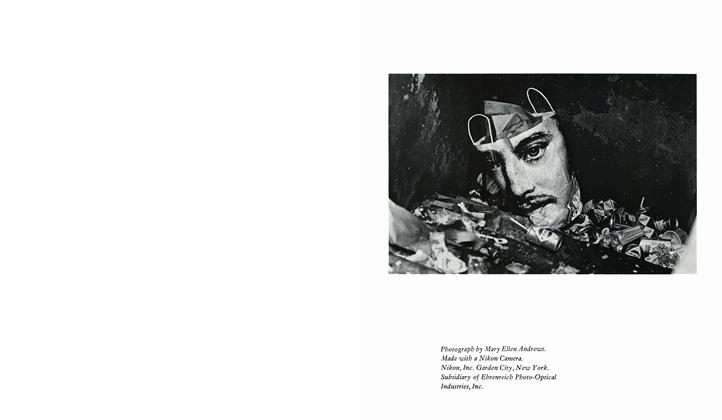

Photograph By Mary Ellen Andrews

Summer 1970 -

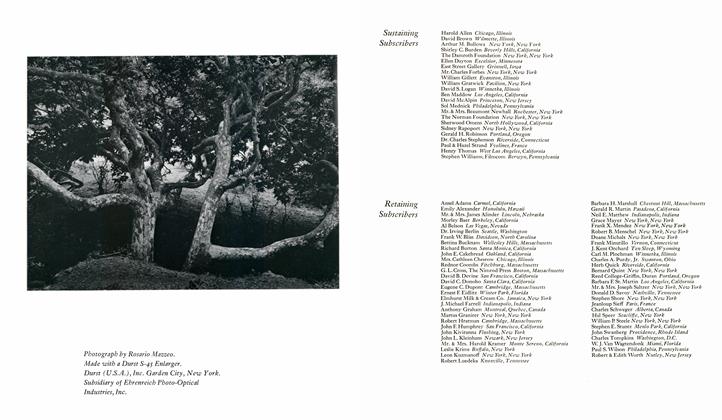

Photograph By Rosario Mazzeo.

Summer 1970

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Haven O’More

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsSilver, Salt And Sunlight

Fall 2012 By Ben Sloat -

Reviews

ReviewsRineke Dijkstra's Portraits

Summer 2005 By Laurie Hurwitz -

Reviews

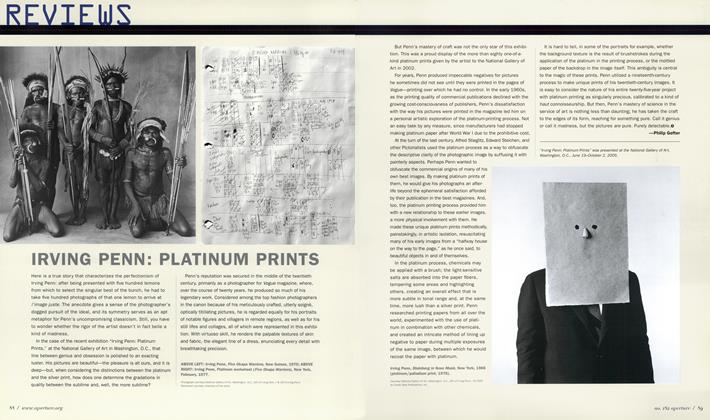

ReviewsIrving Penn: Platinum Prints

Spring 2006 By Philip Gefter -

Reviews

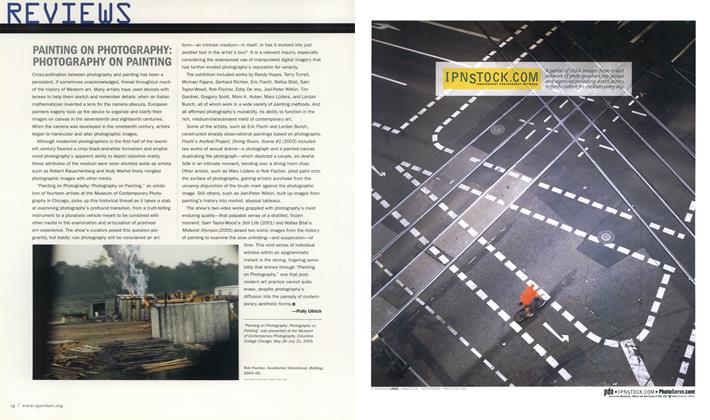

ReviewsPainting On Photography: Photography On Painting

Spring 2006 By Polly Ullrich -

Reviews

ReviewsLes Choix D'henri Cartier-Bresson

Spring 2004 By Vicki Goldberg -

Reviews

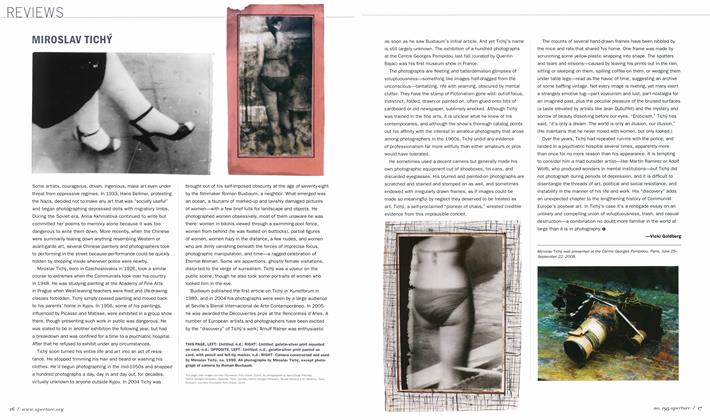

ReviewsMiroslav Tichý

Summer 2009 By Vicki Goldberg