Is Anyone Taking Notice?

Mark Holborn

Aeschylus, the progenitor of tragedy, is remembered on his tomb not as a dramatist or poet, but as a veteran of the battle of Marathon. Having survived the Persian Wars he lived to see the ordeal of invasion give way to stability; suffering was the inevitable route to wisdom. The refrain of the chorus in Agamemnon, “Cry sorrow, sorrow —but let good prevail,” derives its conviction from the voice of a man who had seen a battlefield, not conjured it in his imagination. The tyranny and carnage that Aeschylus had witnessed were to be purged by the ennobling, ritual spectacle of the tragedy.

Today our battlefields are on other continents, but we are all witnesses. We exorcize the tragic through banality or the disaster movie. When the tragedy is immediate, the role of witness is more than disconcerting; it touches areas of our common impotence. Athens and glorious democracy fade into ancient history.

In 1916, on the eve of the Revolution from which we might measure our own history, the poet Osip Mandelstam wrote of the black sun, an image from Euripides. The omen of doom, his poet’s prophecy, has been confirmed. The messengers of our time have filled the airwaves and their dispatches with images of savagery. There are nightmare places where the radio speakers and televisions can never be turned off. However insulated we are by privilege or culture, the news is coming. There is no escape. The witness can be as trapped as the victim.

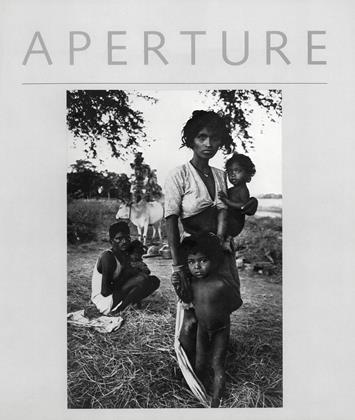

In September 1971 The Sunday Times Magazine published twelve of Don McCullin’s photographs from West Bengal. The same year his first book, The Destruction Business, was published in London, and his second, Is Anyone Taking Any Notice? was published in Cambridge, Massachusetts, with a text taken from Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s 1970 acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for Literature. From the cover of the magazine, a close-up of the faces of a mother and child, to the center spread, his photographs from Bengal stared straight into the face of grief. For days in the summer of 1971 the refugees had walked to the Indian border to escape the troops of General Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan in East Pakistan. They crossed through floods to die in the mud from cholera and starvation, or else to wander on to Calcutta. McCullin probed close to the eyes of the victims and on his own admission came near to ducking from his viewfinder. The following summer I saw many of the survivors in the refugee shanty towns of Calcutta or in the other countless sores of the city. The scale of the event remains inconceivable even in the depths of Calcutta. There is no eradication of those pictures from memory.

In August 1972 I arrived at Jaipur, the city of pink stone laid out by the eighteenth-century astronomer Jai Singh II. I wanted to inspect the observatory, then to admire the water gardens of the old Mogul city of Amber. I stopped at the railway station to eat. There, on a bare platform squatted a mother holding a child of five or six who was dying of starvation. A baby crawled a few feet away. Restaurant customers passed back and forth over her grief-stricken form. It was my turning point. I stopped, stared into her face, and began to talk, but the words meant nothing. I reached for money, but I felt as if I were offering to put a price on the child’s head. Eventually a crowd gathered, not to help the mother and child but to observe me —a naïve fool. Three days later I met the same woman on a train; she smiled with resignation at her good fortune: at least she still had the baby. I left the country immediately. No longer did I have time for Mogul palaces. Repeatedly I returned to the memory of McCullin’s photograph on the magazine cover, which was now indistinguishable in my mind from the face I saw at Jaipur. I remembered the irony of one of the captions beneath his pictures:

Railway stations near the border are so packed with refugees that to board a train one has to clamber over hundreds of sleeping bodies, past crying children covered in flies, amidst constant squabbles occasioned by would-be travellers who can’t afford tickets, or refugees claiming territorial rights to a few inches of ground. Yet, ironically, the Ladies’ First and Third Class waiting rooms at these railway stations are swept clean and always locked.

McCullin’s published pictures from Bengal are the products of one or two days in a career of twenty years that has taken him to every anguished corner of the globe. Behind the compassion of his work is a rage aimed at our indifference. The responsibility for his work lies not in the hands of enlightened editors, but is shared by us all. His pictures offer no cathartic spectacle; to look into them is not to purge your conscience, but to question it. Susan Sontag once too easily compared W. Eugene Smith’s photographs of mercury-poisoned victims in Minamata to Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty. The theater of war like tragedy is common language; it is the jargon of generals. If those ravaged in the mud form McCullin’s theater, we are not just the spectators, we share the stage.

Much has been written about the legend of McCullin; more would detract from his work. He needs a shield of anonymity to prevent his reputation from overriding the content of his pictures. It may relieve us to see him as a hero of wars that are rough but also as safe as cinema. Through the honest confessions he has made in many interviews he may ease himself. In contrast to his pictures, his autobiographical text to his book Homecoming (1979) is awkward passion. McCullin was a child evacuee from the London Blitz and by early adolescence intimate with death. He comes from the closed world of poverty, which in England is sealed by the distinctions of class. For all that, the deprivations of his childhood are less significant than the instinct that has led him to the center of a greater violence and the intuitive ability to contain and structure it.

In McCullin’s first published story, “The Guv’nors of Seven Sisters Road” (1961), the “Guv’nors” pose framed by the rafters of a half-demolished house. Street violence and gang life are part of the raw autobiography of the young McCullin running wild in the wastelands of a bombed-out North London. From John Osborne to John Lennon the English have celebrated the working-class heroes of the postwar era. This was the time when the implications not only of World War II, but of the world war of a previous generation were registered. The old order of Britain had passed, and those outside privilege had begun to articulate their bitterness and wounds publicly with anger. The Guv’nors strut in arrogant style, sneering from a structure that has crumbled all around them.

In the same year, married and unemployed, McCullin saw a news bulletin about the Berlin Wall. With the last of his money he bought a ticket to Germany. The ruins of Berlin from 1945 still stand along the perimeter of the western sector. They shelter snipers and lookouts. The windows are bricked up to prevent leaps from East to West. I remember in 1967 walking across the narrow space between the two sectors, and watching the dogs, attached by their collars to a cable that ran the length of the trench in which they prowled. Such ingenuity, thought to be symptomatic of the Cold War climate, still survives. Berlin in 1961 was McCullin’s first foreign story. His intuition was guiding him closer to the no-man’s zone.

In 1964, in the half light of the morning mist in an orange grove in Cyprus, McCullin witnessed women looking for their husbands, who lay dead among the trees after a battle between Greeks and Turks. McCullin’s eye sensed poetry in the heightened expectation of dawn. The softened early light gave way to brutal discoveries in the dew. He was close enough to aim his camera straight at the face of the mother as her son reached up at the appalling moment when her expression broke. McCullin said he hid behind his camera. The instrument of his vulnerability was also his protection. It is revealing that the beauty of the morning, which he described as poetic, should result in a photograph of such unmitigated pain. His work in Cyprus, first published in The Observer, won him an international reputation and the World Press Photographer Award—an uneasy prize in the circumstances. In the streets of Limassol, surrounded by five thousand Greek irregulars, he charged his pictures with the adrenalin of the street drama. The battle took place in people’s homes. Victims were gunned down in their front rooms, and the drama was tinged with domestic intimacy. McCullin does not claim to have taken these photographs of grief, but accepted them through his camera. He reduced the generalities of war to the specific and touched the most vulnerable areas of our own response. The moment is not stolen or fixed; its potency reverberates.

One dark, formal composition from Cyprus has none of the pace of the other pictures. It is a slowly measured, mournful interior, reminiscent of the sparse rooms of Josef Koudelka’s gypsies. A boy kneels by the body of his father surrounded by seated women, while men stand framed in the light of the open doorway. The scene is pitched in deep silence, with none of the howl of battle. Like Eugene Smith’s photographs of women in “Spanish Village,” the picture is ceremonial and iconographie. It triggers a religious passion.

In the context of magazines, where pictures appear sandwiched between advertisements, McCullin found the most public medium. Its contrasts served both to exaggerate and to insulate us from the horror contained. His pictures reached far beyond the illustrative arguments of photojournalism. His reportage was condensed to single images, which challenged all the surrounding content of the magazines in which they appeared. His work confronted the rapidly consumable, ephemeral nature of the medium. If heeded, a single photograph by McCullin could change events.

McCullin has sometimes been linked with Roger Fenton, often described as the first war photographer for his work in the Crimea. Between March and June 1855, Fenton traveled under British royal patronage with the assistance of the Secretary of State for War. His pictures are as significant for what they omit as for what they include. While The Times Special Correspondent William Russell shocked English consciences with vivid accounts of conditions among the wounded, Fenton did little to challenge Victorian sensibilities. In his most powerful photograph, The Valley of the Shadow of Death, he transformed a quiet, empty valley into a symbol of desolation. Felice A. Beato is much closer to being McCullin’s nineteenth-century predecessor. In i860 Beato, who had previously photographed the fall of Sevastopol and the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny at Lucknow, accompanied the British expeditionary force to China with Charles Wirgman, a free-lance illustrator and correspondent for The Illustrated London News. Beato’s photographs later appeared in the magazine as wood engravings. He joined the attack on the forts at Taku, where the Chinese resisted the advancing British troops with a medieval cannon and crossbows. After the battle at the Inner North Fort, Beato pointed his camera at the bodies and made three photographs at the same point in a breached wall. These pictures represent an attempt to reduce the mass of detail to a simplified, uncluttered image, which could be retained and would be able to penetrate the defensive filters of the viewer. Beato showed what Fenton had witnessed and described in his diary, but had never revealed in his photographs: that in war the dead are no more than the debris of the battlefield.

(continued on page 30)

The Crimea was the last parade-ground war and the first war to fall under the scrutiny of the media. Fenton’s work countered rather than substantiated Russell’s reports, but Russell managed to produce specific improvements in conditions. On the Russian side, Tolstoy, who was an artillery officer at Sevastopol, was sending his Sevastopol Sketches to Nikolai Nekrasov’s magazine, The Contemporary. They touched liberal consciences from the imperial family to the intelligentsia of Saint Petersburg. Tolstoy was greatly impressed by Stendhal’s battle descriptions in The Charterhouse of Parma, but he wanted to go beyond fictional war to realistic documentary narrative.

Hundreds of bodies . . . now lay with fresh blood stains on their rigid limbs in the dew-covered flowery valley dividing the bastion from the trenches and on the smooth slabs of the mortuary chapel at Sevastopol. Hundreds more, with curses and prayers on their cracking lips, crawled, writhed or groaned among the corpses in the flowering fields, or on stretchers, camp cots and the blood-soaked boards of the ambulance station. (Tolstoy, Sevastopol Sketches in Henri Troyat, Tolstoy)

Early in 1855 Tolstoy wrote in the opening of A Plan for the Reform of our Army, “We have no army, we have a horde of slaves cowed by discipline, ordered about by thieves and slave traders.” The disastrous war led directly to Alexander’s Great Reforms and in particular to the Emancipation of the Serfs in 1861, which was to transform feudal Russia to a capitalist state, and to lead to eventual Revolution. Tolstoy’s reports helped to provoke the movement that led to monumental events in history. The reportage of war can change the course of a nation.

The Vietnam conflict was the “greatest” and last media war. Today’s military protagonists are aware of their vulnerability to image; the press is confined to the outer peripheries of the war zone. The secret war, without cameras, where no prisoners are taken, tempts those whose ideology is dubious and whose intentions contradict their results. The picture story, the root of photojournalism, was based on the power of the image over the written word: the photograph can articulate emotions and observations that elude language. The Vietnam war coincided with the debasement of public language. The inventive nature of a new vocabulary reduced war machines to the clatter of abbreviated letters. A unit of flame throwers became the “Zippo Squad,” and the famous general “zapped” the Vietcong from his helicopter. Language had turned in on itself and we were turning deaf. In theory, a serious casualty in Vietnam could be transferred from the combat zone to a special hospital in Japan within twenty-four hours, about as long as it took to file and broadcast a television report. It took eight years for Michael Herr, one man from a regiment of press, to articulate his Dispatches (1977) in a book. The narrative structure of the picture story was redundant. With the world-wide publication of his photograph of the falling Spanish Republican, Robert Capa had demonstrated a reduced, singular reality in 1936. The camera was as fast as death.

At the end of his journey upriver to find Kurtz in Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s narrator says, “I have wrestled with death. It is the most unexciting contrast you can imagine. It takes place in an impalpable greyness, with nothing underfoot, with nothing around, without spectators, without glory, without the great desire of victory, without the great fear of defeat, in a sickly atmosphere of tepid scepticism, without much belief in your own right and still less in that of your adversary.” Seventy-eight years later the impalpable grayness has been confirmed. It lingers in McCullin’s Vietnam work, streaked in black blood.

Francis Ford Coppola sustained his apocalyptic vision of Vietnam with the entrancing pyrotechnics of his film. In the upper reaches of Kurtz’s river the carnage was executed with a diamond will. Coppola’s Kurtz was reading the literature of myth and realised a strange dream denied by the outside world. Conrad’s Kurtz crossed into a no-man’s zone far beyond books to find the appalling vacuum of “The horror! The horror!” McCullin exposed the emptiness of that truth. It surfaced by the walls of the citadel at Hué in the shell-shocked face of the G.I. with his hands locked on the barrel of his gun. The photograph is pivoted towards his half-seen eyes projecting from that space at the center of a maelstrom.

The frailty of the human body arouses emotions at the deepest levels of our common subconscious. Battle rearranges limbs and contorts forms into crisis patterns witnessed only in moments of intense exertion of rage and love. In McCullin’s photographs at the citadel at Hue during the Tet offensive, limbs reach out to touch and intertwine. The wounded are dragged to shelter in an embrace.

Running and crawling through the rubble in the fragmented whine of battle, while the troops moved on, dazed by fatigue and the proximity of their deaths, McCullin found order. Charred, wooden uprights frame the heroic, athletic gesture as a black soldier hurls a grenade. Above a body the silhouette of a bayonet balances the line of an intravenous drip bottle. The details glitter. Rings, bracelets, watches, broken glasses or a crucifix flash conspicuously as familiar, intimate forms in a territory where matter is smashed. In one image of a spilled wallet, ammunition is strewn over the photograph of the corpse’s family. Touching on all the sentiments attempted by propagandists, McCullin twists the image and aims his compassion not at a hero, not for the»cause, but at the other side, at the anonymous adversary. Moving with pure reflex, McCullin still finds an icon. The soldier shot in his legs is carried by his two companions. Through the blurred, unfocused diagonals is a Deposition from the Cross.

Ed Adams’s renowned photograph of the Saigon shooting of a Vietcong suspect, syndicated all over the world through Associated Press, became like Capa’s photograph of thirty years before, indelibly printed on our awareness of that war. It may have convinced the world at large that the war was untenable and so fulfilled the aims shared by the other photojournalists of the time, such as Larry Burrows, Philip Jones-Griffiths, and McCullin himself. The strength of Adams’s photograph hangs on the precision of its time. The instant of another’s death becomes a projection of our own unimaginable deaths.

McCullin’s imagery does not reflect the precision of time but its extension. An icon is the agent by which compassion transcends its own time. By passing the temporal or geographical boundaries it is not depoliticized, it acquires the echo of history. To assume that McCullin in the role of photojournalist is divorced from art or history is as false as to assume that great art exists in a political vacuum. As a witness Goya intensified the rage of his polemic with currents of a deeper lineage. The frontispiece of his Disasters (1863) showed a half-buried, skeletal man surrounded by the ghouls of war, writing on a blank page his final word, “Nothing.” From that vacant point Goya launched the great catalogue of the horrors of the flesh. He portrayed women not only as the ravaged victims, but also as the heroes of the Peninsular War, with no uncertain political message. The face of the man with outstretched arms in the brilliant white spotlight, whose eyes stare into the barrels of the dark, anonymous firing squad in The Third of May, 1808 (1814), is painted again five years later in Goya’s Christ on the Mount of Olives.

In our own century photographs have served to characterize a nation’s entire history. The Russian photographs taken between Hitler’s invasion and his defeat, first published in the West in 1978, touched the most tragic pulse of national events. Their original context and publication are of great interest, but their greater value is the reassertion of that intangible force Tolstoy had identified at Borodino or along the wastelands of Napoleon’s retreat. This was the core of Russian destiny, the assaulted but inviolable Mother Russia, for whom twenty million died between 1941 and 1945.

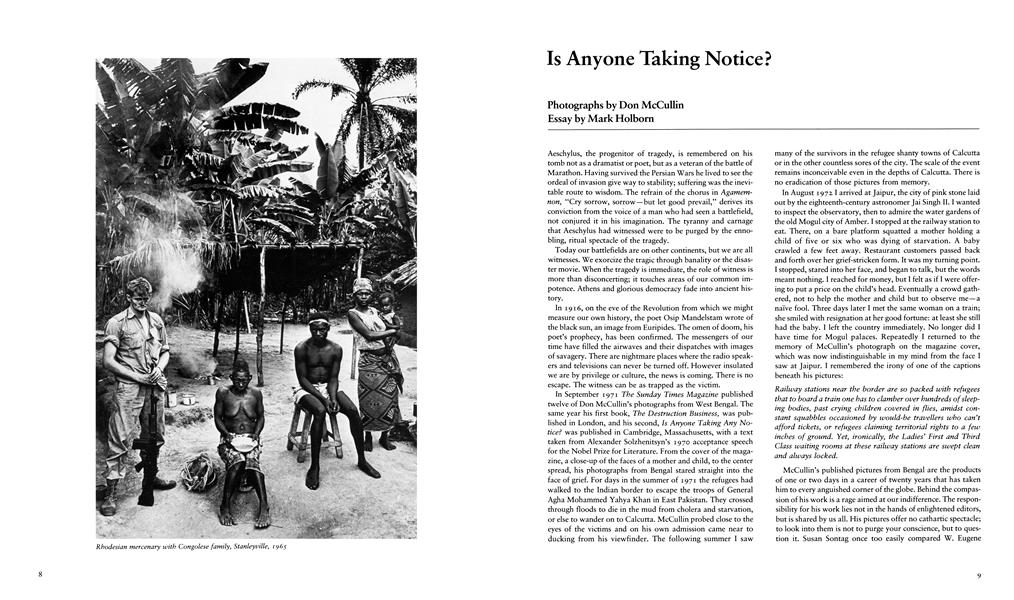

The twenty years of McCullin’s work span many multiples of millions. McCullin’s duty was also to uncover those areas that had no history. In Stanleyville in 1967 he photographed the distorted face of the Rhodesian mercenary standing by the dejected Congolese family. The white man holds a gun; the blacks hold a bowl and a baby. This articulate, composed statement reveals the face of colonial power. When McCullin reached Biafra in 1969 the Biafran nation was only two years old. The history of the Republic had ended by January 1970. In that short time Kwashiorkor disease had turned the children’s hair red and reduced their limbs to matchsticks. The genocide inflicted on the Ibo people was executed with the aid of both Soviet Mig fighters and a steady supply of arms from a “neutral” British government. “We discovered that if we let our hands dangle among the children, a child would grasp each finger or thumb —five children to a hand. A finger from a stranger miraculously would allow a child to stop crying for a while,” wrote Kurt Vonnegut, who left in the final month of Biafra. McCullin’s pictures among those “shoals” of children are nearly all of bones, bellies, and dry sacks of breasts. There are no points of reference, no complexities or subtleties of implication. They are direct and relentless. For once, the popular format of The Sunday Times Magazine, which had so ambitiously used his work since 1966, was insufficient. McCullin had posters made of the prematurely senile mother with child at her impossible breast with the caption, “The British Government supports this war. You, the public, could stop it.” While it was defaced in the London suburbs, it was pinned to the wall in a home in Prague.

The events of our time are so overwhelming that McCullin returns frequently to his impotence to change those events. He may have succeeded far beyond what he imagines, but ultimately the enormity of the events cannot be contained in the camera or in language. The wounds that were splattered from Hue to The New York Times to the Sunday color supplement are in turn replaced by combat zones of our own imagination. John Szarkowski realized this when he championed Diane Arbus as the photographer closest to a common, contemporary wound. Her work, a private vision, may form the perfect, illogical sequence to McCullin. She attempted to describe the indescribable. She felt she was crawling on her belly across a minefield.

In Bengal in 1971 McCullin photographed a child being bathed to cool the first stages of the cholera fever. She is being anointed. It is a baptism of polluted water. A young husband carries his wife, dying from the same disease. The whites of her eyes are turning, unseeing, but her husband stares straight through McCullin’s camera —a passion play in the mud of another continent. Somewhere in a small mid-American town, or in the suburb of a great European city, or on the edge of a new town housing development, there is a child wounded not from famine or the shrapnel of antipersonnel shells, but from an imagination that is too true or eyes that see beyond the solace of adult aspirations, it has already been written by Aeschylus: “Man grows wise against his will.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Notes For A Portrait Of Lisette Model

Spring 1982 By R. H. Cravens -

Reconciliation With Geography

Spring 1982 By Robert Adams -

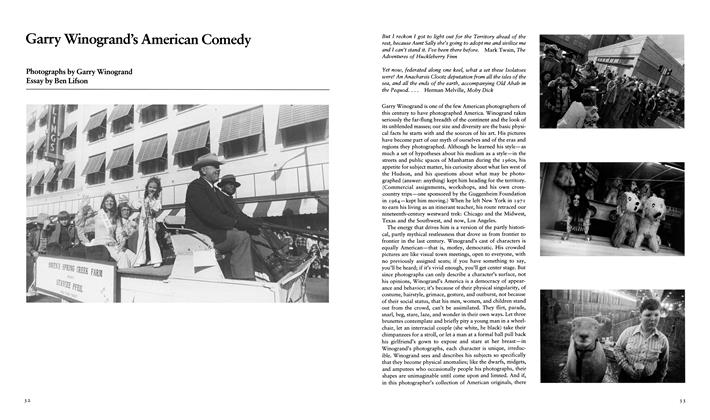

Garry Winogrand’s American Comedy

Spring 1982 By Ben Lifson -

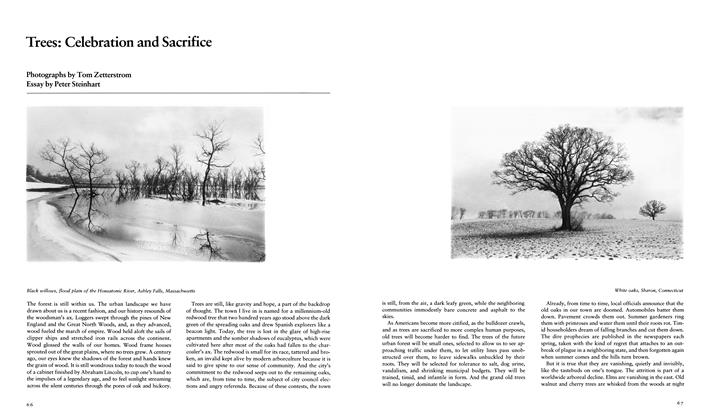

Trees: Celebration And Sacrifice

Spring 1982 By Peter Steinhart -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasBefore Photography

Spring 1982 By Jed Perl -

People And Ideas

People And IdeasPolitics And Photographs: Second Latin American Colloquium On Photography

Spring 1982 By Paul Tarsiers

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Mark Holborn

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasBill Brandt Portraits

Spring 1983 By Mark Holborn -

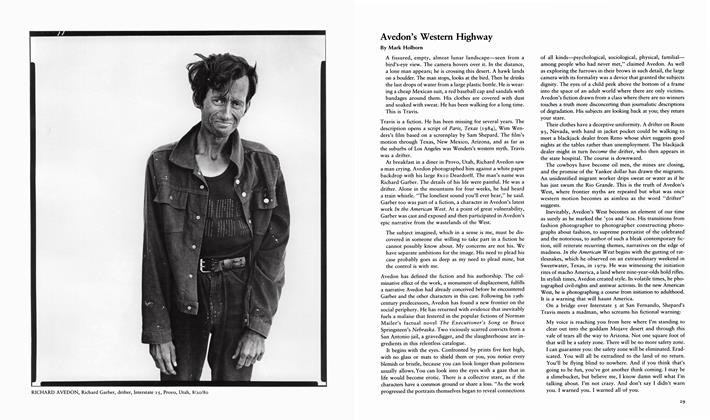

Avedon’s Western Highway

Winter 1985 By Mark Holborn -

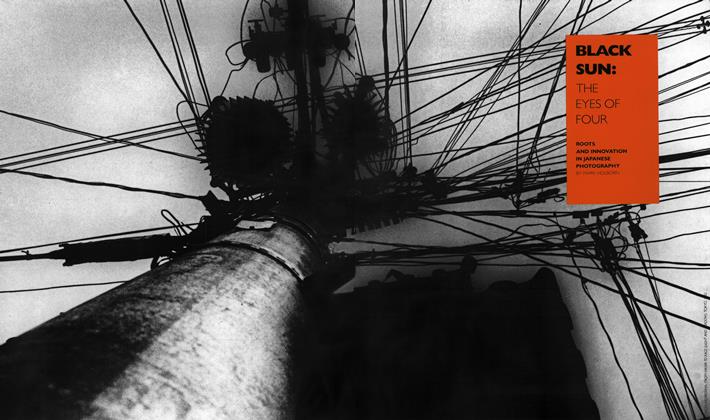

Black Sun: The Eyes Of Four

Spring 1986 By Mark Holborn -

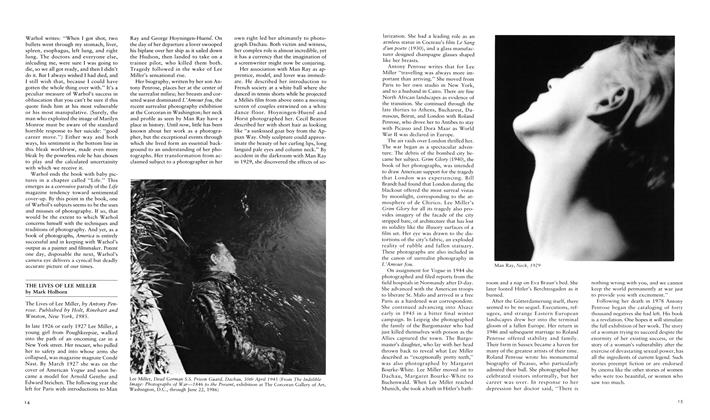

People And Ideas

People And IdeasThe Lives Of Lee Miller

Summer 1986 By Mark Holborn -

Nan Goldin's Ballad Of Sexual Dependency

Summer 1986 By Mark Holborn -

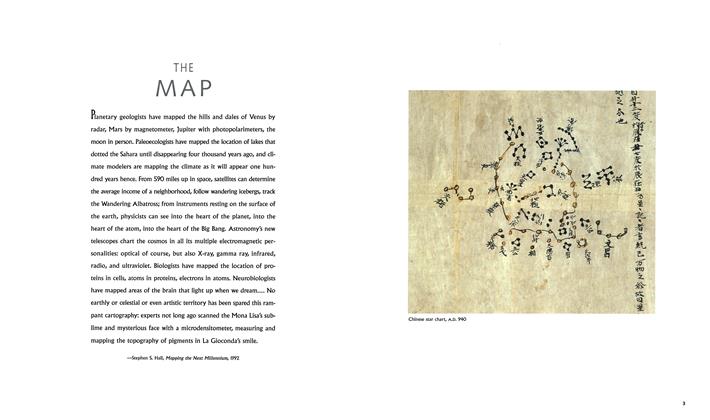

The Map

Fall 1999 By Mark Holborn