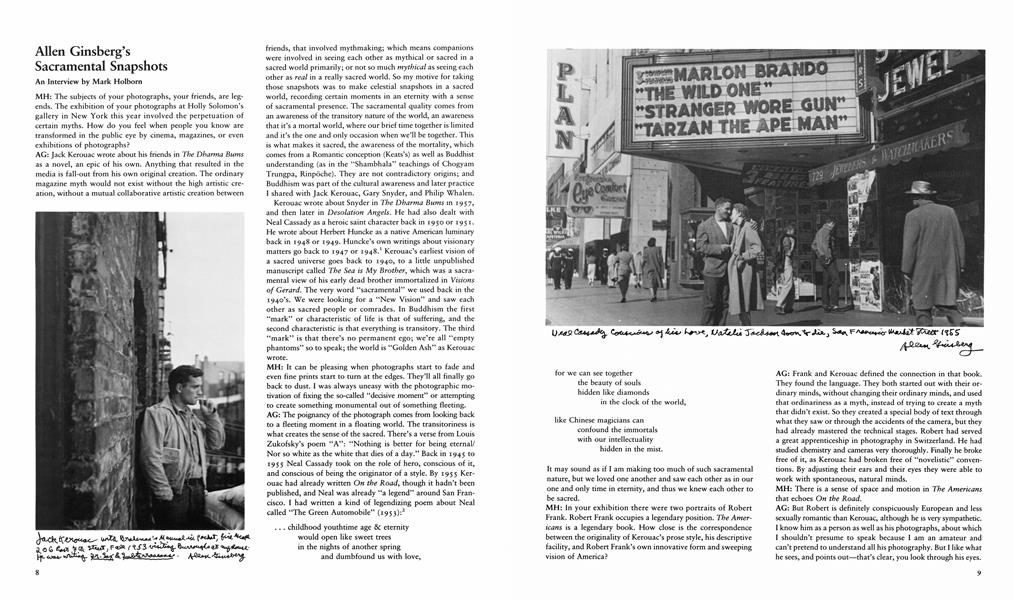

Allen Ginsberg’s Sacramental Snapshots

Mark Holborn

MH: The subjects of your photographs, your friends, are legends. The exhibition of your photographs at Holly Solomon’s gallery in New York this year involved the perpetuation of certain myths. How do you feel when people you know are transformed in the public eye by cinema, magazines, or even exhibitions of photographs?

AG: Jack Kerouac wrote about his friends in The Dharma Bums as a novel, an epic of his own. Anything that resulted in the media is fall-out from his own original creation. The ordinary magazine myth would not exist without the high artistic creation, without a mutual collaborative artistic creation between friends, that involved mythmaking; which means companions were involved in seeing each other as mythical or sacred in a sacred world primarily; or not so much mythical as seeing each other as real in a really sacred world. So my motive for taking those snapshots was to make celestial snapshots in a sacred world, recording certain moments in an eternity with a sense of sacramental presence. The sacramental quality comes from an awareness of the transitory nature of the world, an awareness that it’s a mortal world, where our brief time together is limited and it’s the one and only occasion when we’ll be together. This is what makes it sacred, the awareness of the mortality, which comes from a Romantic conception (Keats’s) as well as Buddhist understanding (as in the “Shambhala” teachings of Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpöche). They are not contradictory origins; and Buddhism was part of the cultural awareness and later practice I shared with Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen.

Kerouac wrote about Snyder in The Dharma Bums in 1957, and then later in Desolation Angels. He had also dealt with Neal Cassady as a heroic saint character back in 1950 or 1951. He wrote about Herbert Huncke as a native American luminary back in 1948 or 1949. Huncke’s own writings about visionary matters go back to 1947 or 1948.1 Kerouac’s earliest vision of a sacred universe goes back to 1940, to a little unpublished manuscript called The Sea is My Brother, which was a sacramental view of his early dead brother immortalized in Visions of Gerard. The very word “sacramental” we used back in the 1940’s. We were looking for a “New Vision” and saw each other as sacred people or comrades. In Buddhism the first “mark” or characteristic of life is that of suffering, and the second characteristic is that everything is transitory. The third “mark” is that there’s no permanent ego; we’re all “empty phantoms” so to speak; the world is “Golden Ash” as Kerouac wrote.

MH: It can be pleasing when photographs start to fade and even fine prints start to turn at the edges. They’ll all finally go back to dust. I was always uneasy with the photographic motivation of fixing the so-called “decisive moment” or attempting to create something monumental out of something fleeting. AG: The poignancy of the photograph comes from looking back to a fleeting moment in a floating world. The transitoriness is what creates the sense of the sacred. There’s a verse from Louis Zukofsky’s poem “A”: “Nothing is better for being eternal/ Nor so white as the white that dies of a day.” Back in 1945 to I955 Neal Cassady took on the role of hero, conscious of it, and conscious of being the originator of a style. By 1955 Kerouac had already written On the Road, though it hadn’t been published, and Neal was already “a legend” around San Francisco. I had written a kind of legendizing poem about Neal called “The Green Automobile” (1953):2

. . . childhood youthtime age & eternity would open like sweet trees in the nights of another spring and dumbfound us with love,

for we can see together the beauty of souls hidden like diamonds in the clock of the world,

like Chinese magicians can confound the immortals with our intellectuality hidden in the mist.

It may sound as if I am making too much of such sacramental nature, but we loved one another and saw each other as in our one and only time in eternity, and thus we knew each other to be sacred.

MH: In your exhibition there were two portraits of Robert Frank. Robert Frank occupies a legendary position. The Americans is a legendary book. How close is the correspondence between the originality of Kerouac’s prose style, his descriptive facility, and Robert Frank’s own innovative form and sweeping vision of America?

AG: Frank and Kerouac defined the connection in that book. They found the language. They both started out with their ordinary minds, without changing their ordinary minds, and used that ordinariness as a myth, instead of trying to create a myth that didn’t exist. So they created a special body of text through what they saw or through the accidents of the camera, but they had already mastered the technical stages. Robert had served a great apprenticeship in photography in Switzerland. He had studied chemistry and cameras very thoroughly. Finally he broke free of it, as Kerouac had broken free of “novelistic” conventions. By adjusting their ears and their eyes they were able to work with spontaneous, natural minds.

MH: There is a sense of space and motion in The Americans that echoes On the Road.

AG: But Robert is definitely conspicuously European and less sexually romantic than Kerouac, although he is very sympathetic. I know him as a person as well as his photographs, about which I shouldn’t presume to speak because I am an amateur and can’t pretend to understand all his photography. But I like what he sees, and points out—that’s clear, you look through his eyes.

MH: Do you remember the filming of Robert Frank’s PM// My Daisy or Me and My Brother?

AG: I remember well. In Pull My Daisy Peter Orlovsky and Gregory Corso were hanging around with Robert and they were glad to act in a film, or more or less act. There wasn’t much need to follow the script too closely. The script was based on a play of Kerouac’s which had never been published. Robert made great use of the accidents of filming. When Kerouac saw the edited film, although he had the background in his mind, he had to start from scratch to make up the narration.

As well as Me and My Brother (a film about Peter and his brother Julius, 1964—66) we made another filnyin 1982 with Corso and Orlovsky at the Naropa Institute in Boulder, called This Is For You Jack. There were about eight different film and video crews at Naropa because there was this big gathering to pay homage to Kerouac, and Robert did something brilliant. While everybody was running around interviewing people or setting up cameras for the lectures, Robert put his camera on the porch where everybody was living and he observed people completely informally. It was very funny. Later we did a little more picture taking together, on video, that had the roughness, scratchiness, and accident of the still photograph. He came by my house and I had just written a little epilogue for Kaddish called “White Shroud” (1983) and I was reading it to him and he started his video camera.

Robert had always been interested in the theme of Kaddish. When I came back from India in 1963, Robert asked me to write a film script on Kaddish. I didn’t have any money. I would go to his house every day or so and write a little scene and get ten dollars or five dollars an hour, which was what I was living on then. I was broke and he had a little money he could afford to pay me. Me and My Brother grew out of that because he didn’t have enough money to film the Kaddish period 1930’s script that I wrote, so he started to film Peter Orlovsky and his mental hospital brother Julius in the present. Anyway the film script was finally finished, and performed by Chelsea Theater in 1971 as a play called Kaddish. I had relied on Robert to teach me how to make a shooting script. The script’ll be published someday, I guess, but there is so much to do. Look at the condition of these negatives and prints. I have 30 years of negatives but I haven’t had the means to print them properly. They are like the journals I keep—30 years of epiphanies and moments that I’ve noticed. So I notice many things, then notice that I notice, and eventually I make a picture of it, as I do with journals, intermittent noticings, which are not really diaristic. I wish I’d had the energy to record all the conversations that I’ve had with Robert, Kerouac, Corso, or Burroughs. When 1 have the energy before I go to bed I might make a note, like taking out a camera. I see more than I have the physical capacity to write about. You can’t photograph everything. It is good to be able to label a thought, to be able to pull it out of your pocket or off your bookshelf one day.

MH: You have been a subject for Richard Avedon, who is regarded as a very great portrait photographer, but he has also been your subject.

AG: Avedon photographed me when I first went over to his studio in 1964. He got interested in photographing me and Peter Orlovsky naked, among some other pictures. Marvin Israel, who designed some albums for Atlantic Records at the time, used one of the Avedon photographs of my face for the cover of a recording of Kaddish that Jerry Wexler put out. Then in the late 1960’s my father Louis had a book published and we had a big party in Paterson, New Jersey. Avedon came out with a whole crew and took photographs of every member of our family with American flags eating apple pie. He was interested in my relationship to my family, which was a big EuropeanJewish-New Jersey family. Avedon got in touch with me this year since it was zo years since he first photographed us and he wanted us to come up to his studio so he could do another naked duo photograph. That first photograph he did was used for a cover of Evergreen Review and as the frontispiece of a book of letters and love poems that I did with Peter Orlovsky, called Straight Heart’s Delight.3 I had my little Olympus XA with me a couple of weeks ago when I went up to his studio; I thought I’d take a picture of him.

Robert Frank has consistently given me help over the last years with my photographs and arranged for Brian Graham, one of his printmaker friends, to make my prints. I was hungry for instruction and thought I would ask Avedon for a little advice. I was always grateful that Avedon saw me as an artist (on his or my own terms) rather than as a public image.

MH: David Hockney worked with his camera to record the surface of daily life and people close to him. Something wonderful happened, not because it was David Hockney, or because Christopher Isherwood was in the corner of the frame; there was something beyond that. A long series of precise descriptions, in themselves no more than essential descriptions, were built up and were culminatively transformed into something more, something that might change the way we look at the world. Do you sense that something as simple as a record of one’s life can become something more?

AG: The epigraph of my book of collected poems is “Things are symbols of themselves”; so friends are symbols of themselves. There is a mythology but finally people are just themselves. Being themselves in a general pragmatic state, they don’t have to symbolize “hero,” they don’t have to symbolize anybody but themselves because apparently they are unable to be anything better, whereas everybody else is trying to become a man of distinction or a Yuppie. Robert Frank is unable to be anything better than what he is, so he has to settle for what he is out of sheer helplessness. I have to settle for what I did or do in my writing because I can’t do any better, mainly because of incompetence, insights, or such genius facility that whatever is done is sufficient in its rhythm or eye. It’s like trying to make out as a heterosexual, which I once tried but didn’t succeed. So I am stuck with what I am, queer. It’s not “sufficient,” as it is, but accepting the insufficiency is realizing the humor of the condition. You just relax. You don’t have to know everything to be perfect (the art is in being there)—like Burroughs who allows things to fall their own way. His cut-ups are his way of cutting out of his obsessions. Robert Frank leaves a certain amount to chance, like Burroughs with his cut-ups. This allows the phenomenal world to speak for itself, instead of aggressively dominating it, telling the world what it is too insistently. I like Elsa Dorfman’s House Book photos too—ordinary life around her house—though it includes a lot of romantic poetface visitors.

MH: Burroughs has a cinematic or photographic quality of prose.

AG: The reason is that Burroughs thinks in pictures, not in words. I remember him in Tangier seated at his desk, with his fingers hovering over a typewriter, and I said, “What are you thinking about, Bill?” and he said, “Men pulling nets from the sea in the dark.” It was an image of the fishermen on the beach of Tangier, before dawn. He can think in moving pictures. Sometimes he creates the quality of old newsreel. “I don’t want to see this old newsreel re-run again,” he might say, laconically. MH: What is the connection between your teacher Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpöche, a Tibetan Buddhist, and your photography? AG: Many of the aesthetic terms I use are his formulations. He practices calligraphy, poetry, tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and photography, as examples of aesthetic perception which involve the three principles of Ground, Path, and Fruition; or heaven, earth, and man; or mind, body, and speech. In aesthetic terms this is equivalent to perception, recognition, and articulation. In Buddhist terms this is equivalent to Body of Law (Dharmakaya); Name and Form (Nirmanakiya); and Body of Intelligence (or Bliss) (Sambhogakaya). That last is the intelligence that communicates between emptiness and form, or background and foreground. In all Taoist aesthetics (as in a theory of perception relating to Robert Frank, Jack Kerouac and my own writing, and in Buddhist art), there is open-minded primordial consciousness, which is consciousness without conceptualization, or what we might call “First Thought.” From this we get First Thought, Best Thought, the title of Trungpa’s book of poems (Shambhala Press, Boulder, CO, 1983) to which I wrote an introduction. So there is open mind, or mind without name or form; and there is also a perception of the ordinary, the earth and the immediate surroundings. Something is needed to bring the heaven and the earth together, which is the appreciator. The appreciator may manifest a very wry appreciation or a humorous appreciation; or a fart, or a poem, or a haiku; or a photograph. That’s Trungpa’s aesthetic based on the Nature of the mind and its thought forms. Or it’s not his aesthetic, but a tradition which links calligraphy, Tibetan poetry, archery, T’ai Chi, and photography. Trungpa’s application of the principle to photography was a very literal, simple-minded inclusion of these “three worlds.” His photographs would include a piece of the sky, a piece of the ground (tree or building), and something that would be his contribution to this chaos, such as a green pepper hanging from a house post.

That practice gave me the way to be spontaneous. I incorporated the principle into teaching poetry. The phenomenon of mind consciousness consists, say, of separate thought forms that have a beginning, a middle, and an end. The beginning is sensation-perception, in open mind without thought; the middle is recognition or conceptualization; and the end is action or reaction, your own comment. This relates to classical Buddhist psychology. The aesthetic is to model the structure of art from the processes of the mind rather than ignoring the mind and creating a structure that covers up the evidence of the mind. MH: Is there a relationship between this process and the writing of William Carlos Williams?

AG: Yes. There are those lines of Williams’s about “Thursday”:

I have had my dream—like others and it has Come to nothing, so that I remain now Carelessly with feet planted on the ground and look up at the sky— feeling my clothes about me, the weight of my body in my shoes, the rim of my hat, air passing in and out at my nose—and decide to dream no more.4

William Carlos Williams here provides a description of primordial mind, recognition of the condition; and the wry comment that he’ll have no more conceptual thoughts. That poem, “Thursday” (like an ordinary day), was written around 1919. Just as Gertrude Stein had studied with the psychologist William James, Williams with his intuition was interested in the practical phenomena of language and the mind. He wrote a number of poems which are very accurate models of how the mind works, such as “Good Night.”5 He described a territory shared by Zen and Tibetan Buddhism.

MH: Is there a leap to be made from this process to the practice of making a photograph or seeing a photograph?

AG: Whose photographs? Mine? Robert Frank’s? Berenice Abbott’s? My photographs appreciate the figure or character or face in the panoramic space of time as in eternity. This is literally the panoramic space of the other side of the apartment; or in the middle of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; or Market Street, San Francisco; or the sky above Kerouac’s brow; Phil Whalen in a chair; Neal Cassady on Market Street; Huncke on Times Square; Burroughs in front of a sphinx in the museum, or on the subway; Jack in 1953 on a fire escape; the gang in front of City Lights bookstore; Gregory Corso on Boulevard Pasteur, Tangier, in 1961; Bill Burroughs and Paul Bowles and Gregory and Allen Ansen in the garden of Villa Mouneria in Tangier beneath a clear sky. There are minute particulars, and photographs involve the noticing of their place in history, time, and space, Tangier or Times Square. The particular person, my subject, is aware of his place as I am aware of his place in space and time. We are assuming that the place and time and space are all sacred and vanishing as a moment in eternity, in which both characters, the subject and the photographer, are aware of the eternity. A vulgar interpretation would be: “These guys knew they were historic,” or “Those guys knew they were mythical.” The mythic element comes from the awareness of the eternal, and the eternal comes from awareness of the transitory, which comes in turn with a recognition of suffering. The pain and the realization of the suffering leads to the sacramental compassion for the nature of the fleeting moment. Kerouac wrote a poem expressing this clearly (for me)—Mexico City Blues’s 54th chorus ends:

On both occasions I had wild Face looking into lights Of streets where phantoms Hastened out of sight Into Memorial Cello Time.6

This interview was conducted following the opening of an exhibition of new acquisitions at the New York Public Library, Feb. 12,1985.

FOOTNOTES 1. The Evening Sun Turned Crimson, Herbert Huncke, Cherry Valley Editions, 1980. 2. Collected Poems 1947—1980, Allen Ginsberg, Harper & Row, NY, 1984. 3. Gay Sunshine Press, San Francisco, 1980. 4. The Collected Earlier Poems, William Carlos Williams, New Directions, NY, 1966, p. 202. 5. Ibid, p. 145. 6. Mexico City Blues, Jack Kerouac, Grove Press, NY, 1959.

California is not so much a state of the Union as it is an imagination that seceded from our reality a long time ago. In leading the world in the transition from industrial to post-industrial society, California’s culture became the first to shift from coal to oil, from steel to plastic, from hardware to software, from materialism to mysticism, from reality to fantasy. California became the first to discover that it was fantasy that led reality, not the other way around.

WILLIAM IRWIN THOMPSON, Unknown California, 1985

Rodeo Drive

Street Level

What is it that radiates from these photographs and makes us blink, giving us the feeling that we have walked those streets, have known their rhythms intimately, but had never viewed them? The Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographs of this same period are salted away yet fabled history. They are like a sad dream, affecting yet remote. Weimar photography had no nominal truck with specific historic incident. With their compounded visual interest, though, Gutmann’s images mature out of it, and sparkle with a bright pathos. The vantage assumed

in many of them is that of the normal pedestrian, but the eye is that of an astonished foreigner. For him, average and nondescript scenes and fixtures, unlikely to be noticed by natives, had a riveting excitement, even a shock value. He could not anticipate what sorts of things would make pictures in this new city, but he had a readiness to see, unheard of among anyone who lived there.

MAX KOZLOFF, The Extravagant Depression, 1984

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

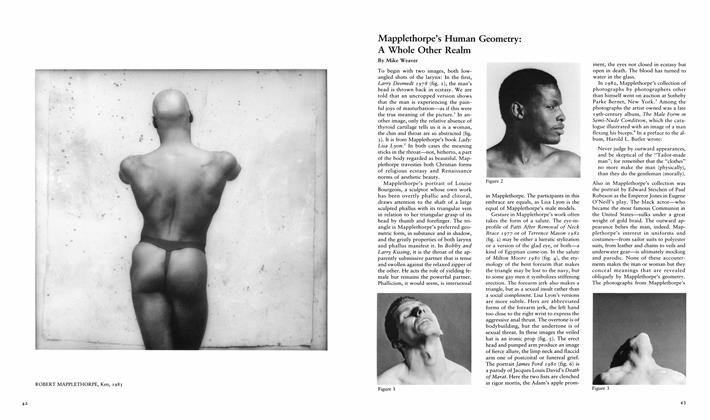

Mapplethorpe’s Human Geometry: A Whole Other Realm

Winter 1985 By Mike Weaver -

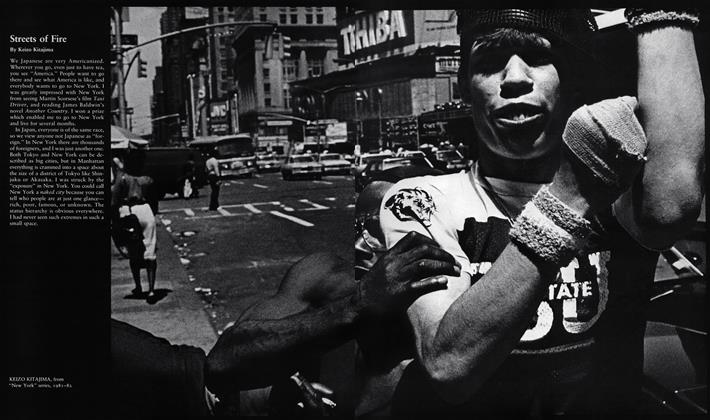

Streets Of Fire

Winter 1985 By Keizo Kitajima -

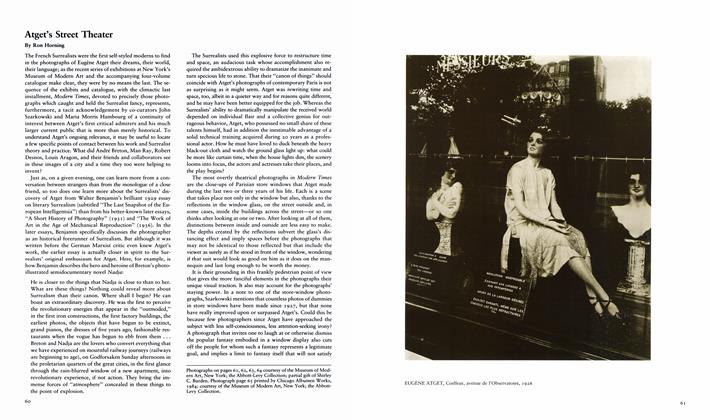

Atget’s Street Theater

Winter 1985 By Ron Horning -

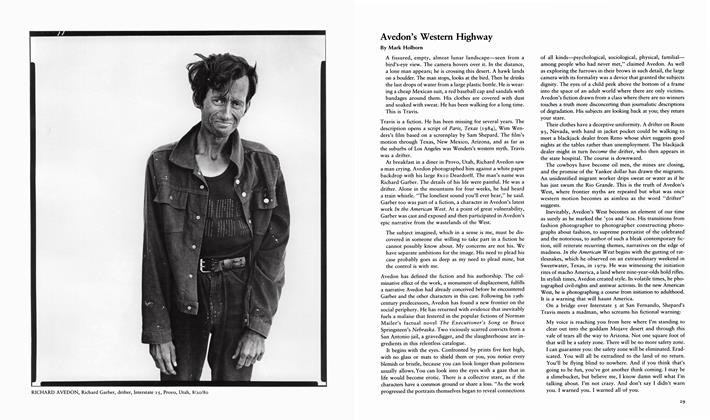

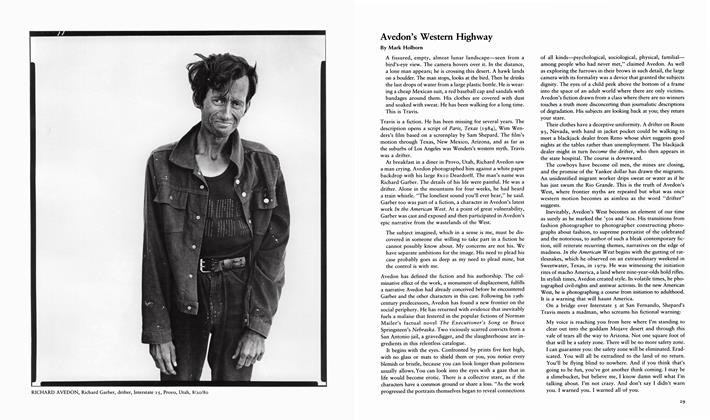

Avedon’s Western Highway

Winter 1985 By Mark Holborn -

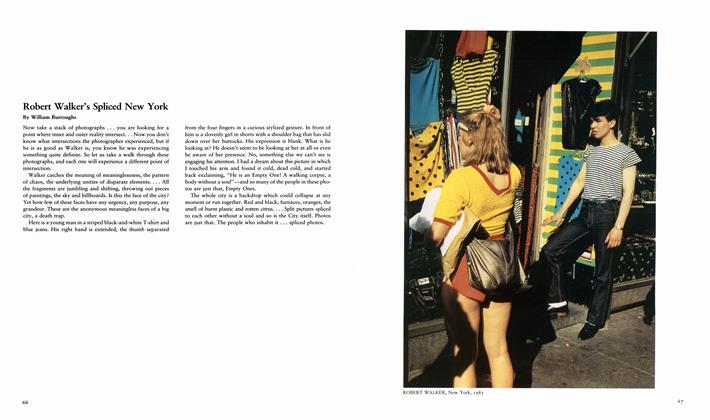

Robert Walker’s Spliced New York

Winter 1985 By William Burroughs -

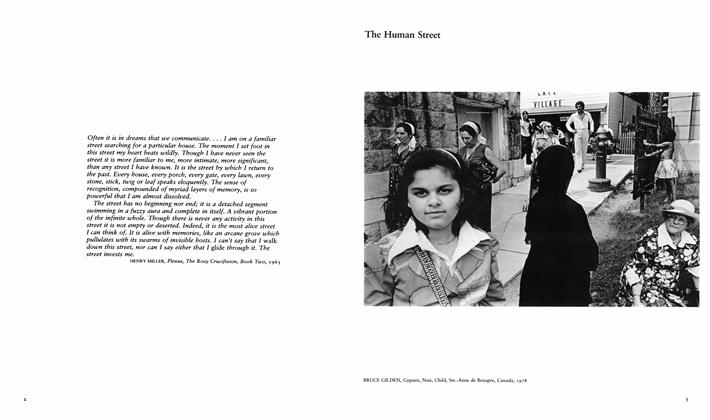

The Human Street

Winter 1985

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Mark Holborn

-

People And Ideas

People And IdeasGilbert & George Storm America's Citadels

Winter 1984 By Mark Holborn -

Color Codes

Fall 1984 By Mark Holborn -

Avedon’s Western Highway

Winter 1985 By Mark Holborn -

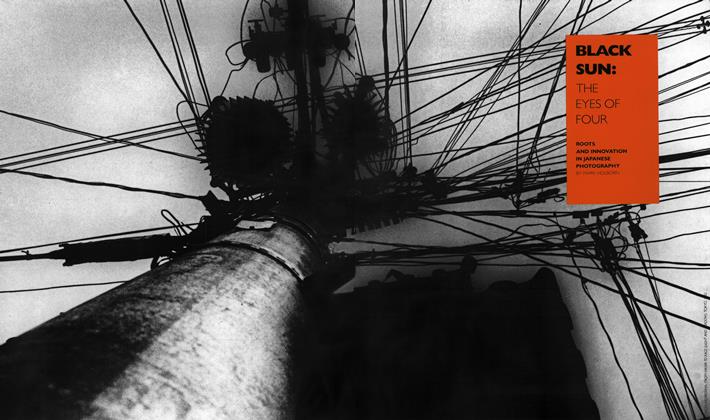

Black Sun: The Eyes Of Four

Spring 1986 By Mark Holborn -

People And Ideas

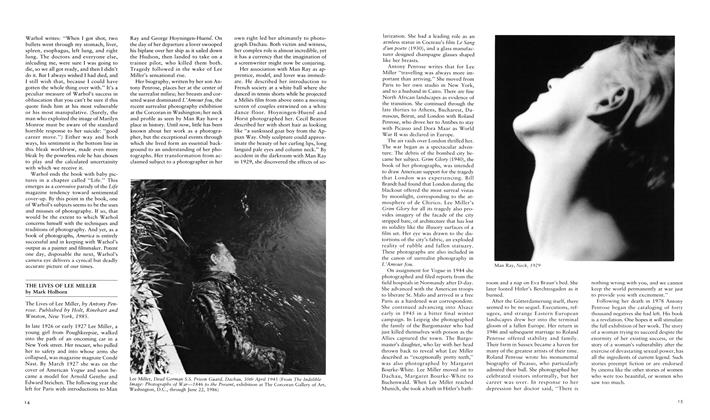

People And IdeasThe Lives Of Lee Miller

Summer 1986 By Mark Holborn -

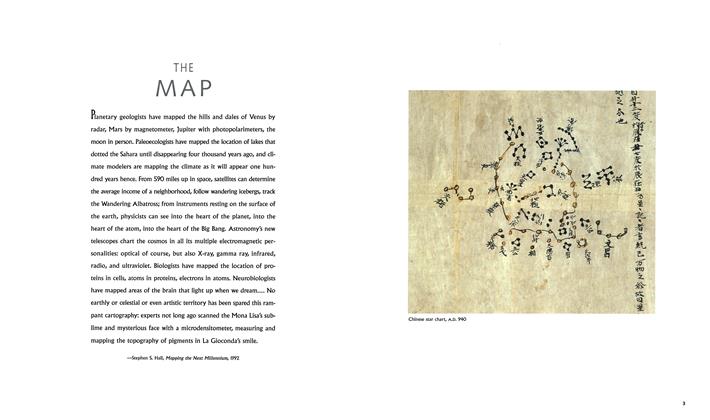

The Map

Fall 1999 By Mark Holborn