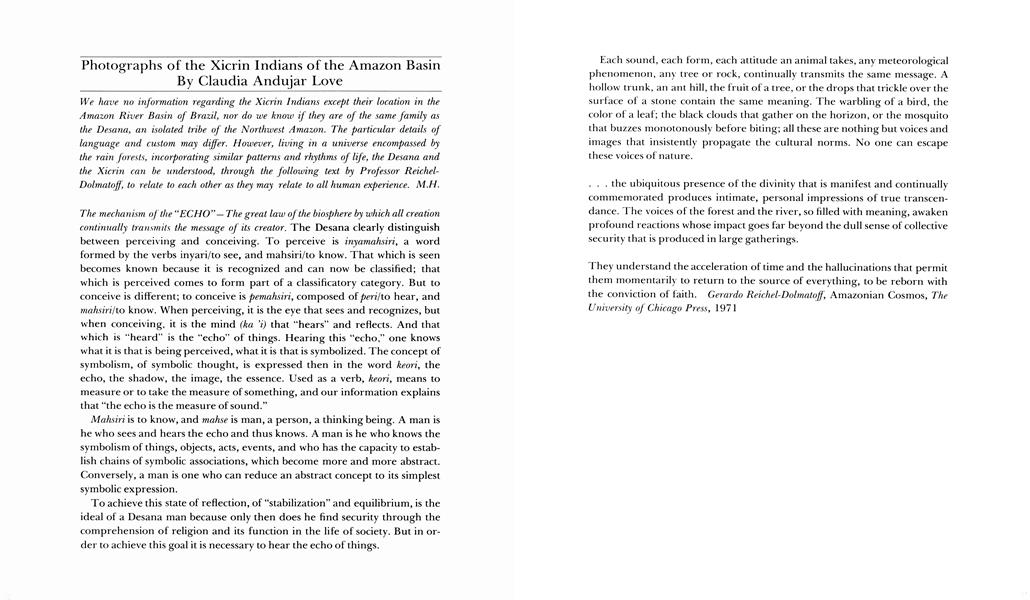

We have no information regarding the Xicrin Indians except their location in the Amazon River Basin of Brazil, nor do we know if they are of the same family as the Desana, an isolated tribe of the Northwest Amazon. The particular details of language and custom may differ. However, living in a universe encompassed by the rain forests, incorporating similar patterns and rhythms of life, the Desana and the Xicrin can be understood, through the following text by Professor Reichel-Dolmatoff, to relate to each other as they may relate to all human experience. M.H.

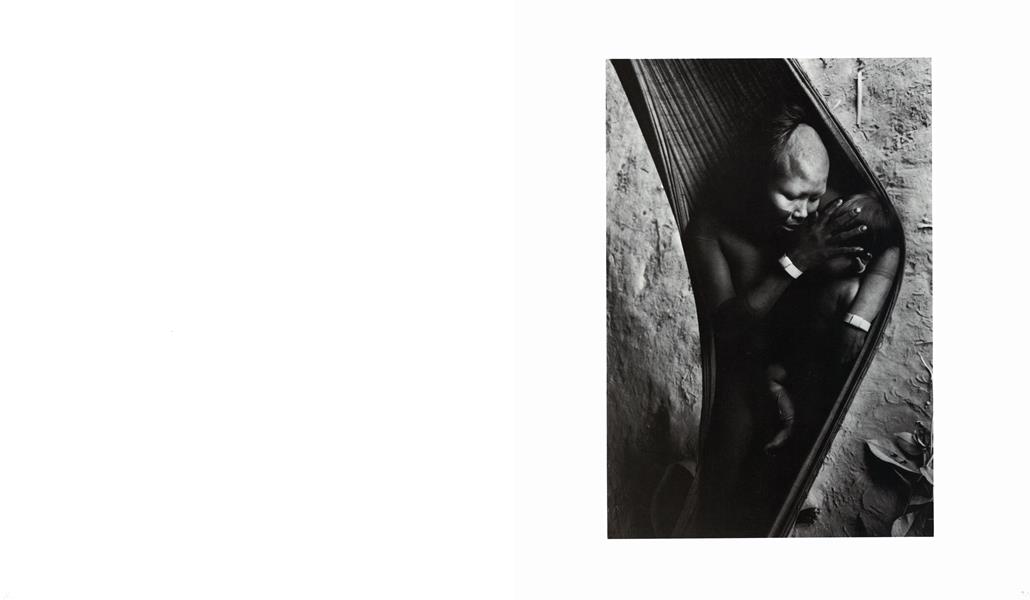

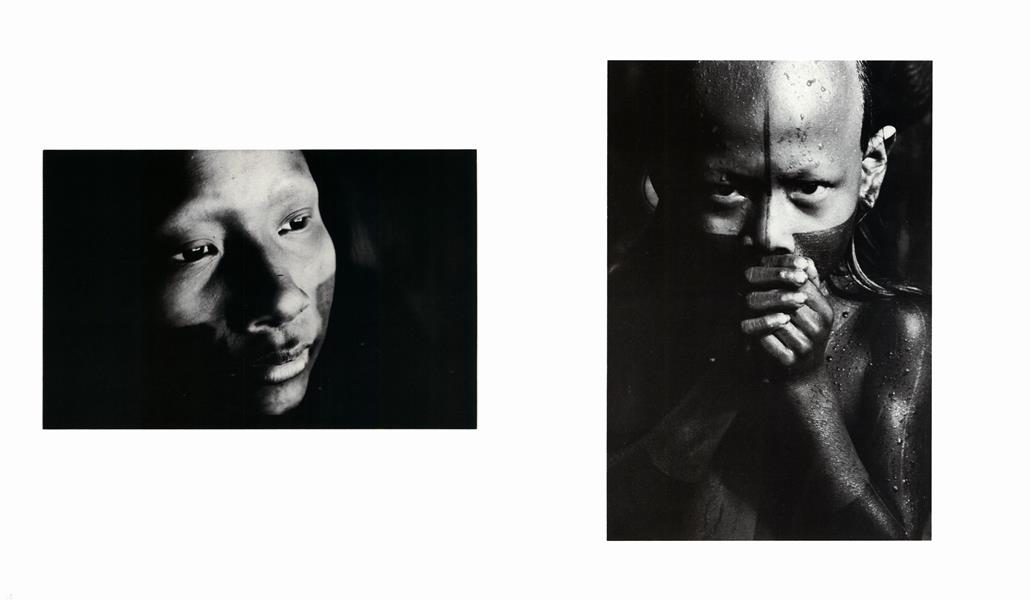

The mechanism of the “ECHO” — The great law of the biosphere by which all creation continually transmits the message of its creator. The Desana clearly distinguish between perceiving and conceiving. To perceive is inyamahsiri, a word formed by the verbs inyari/to see, and mahsiri/to know. That which is seen becomes known because it is recognized and can now be classified; that which is perceived comes to form part of a classificatory category. But to conceive is different; to conceive is pemahsiri, composed of peri /to hear, and mahsiri/to know. When perceiving, it is the eye that sees and recognizes, but when conceiving, it is the mind (ka ’i) that “hears” and reflects. And that which is “heard” is the “echo” of things. Hearing this “echo,” one knows what it is that is being perceived, what it is that is symbolized. The concept of symbolism, of symbolic thought, is expressed then in the word keori, the echo, the shadow, the image, the essence. Used as a verb, keori, means to measure or to take the measure of something, and our information explains that “the echo is the measure of sound.”

Mahsiri is to know, and mahse is man, a person, a thinking being. A man is he who sees and hears the echo and thus knows. A man is he who knows the symbolism of things, objects, acts, events, and who has the capacity to establish chains of symbolic associations, which become more and more abstract. Conversely, a man is one who can reduce an abstract concept to its simplest symbolic expression.

To achieve this state of reflection, of “stabilization” and equilibrium, is the ideal of a Desana man because only then does he find security through the comprehension of religion and its function in the life of society. But in order to achieve this goal it is necessary to hear the echo of things.

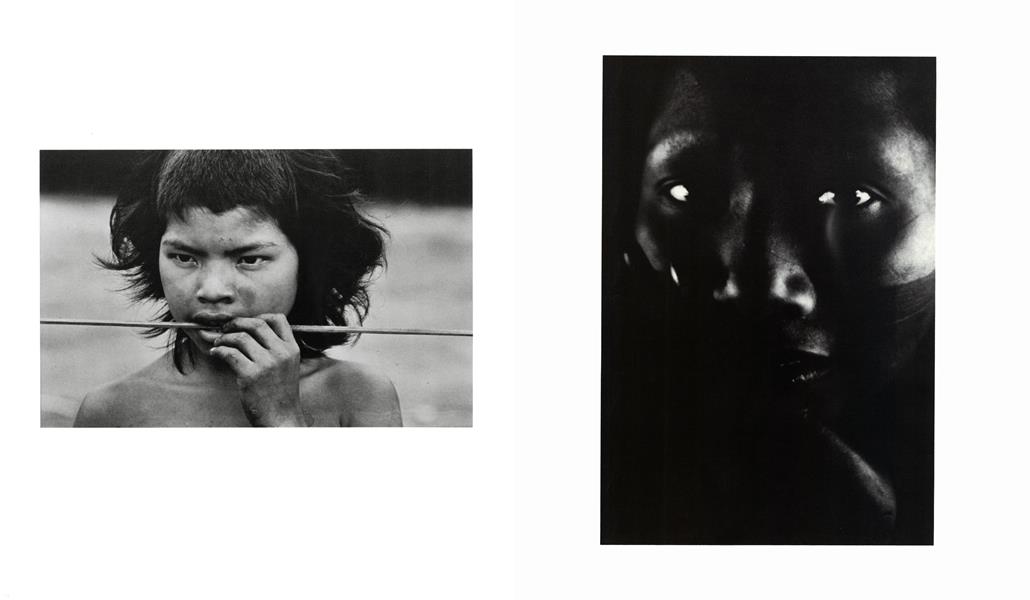

Each sound, each form, each attitude an animal takes, any meteorological phenomenon, any tree or rock, continually transmits the same message. A hollow trunk, an ant hill, the fruit of a tree, or the drops that trickle over the surface of a stone contain the same meaning. The warbling of a bird, the color of a leaf; the black clouds that gather on the horizon, or the mosquito that buzzes monotonously before biting; all these are nothing but voices and images that insistently propagate the cultural norms. No one can escape these voices of nature.

. . . the ubiquitous presence of the divinity that is manifest and continually commemorated produces intimate, personal impressions of true transcendence. The voices of the forest and the river, so filled with meaning, awaken profound reactions whose impact goes far beyond the dull sense of collective security that is produced in large gatherings.

They understand the acceleration of time and the hallucinations that permit them momentarily to return to the source of everything, to be reborn with the conviction of laith.

—Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff, Amazonian Cosmos, The University of Chicago Press, 1971

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Native America

-

Pictures

PicturesGuadalupe Maravilla

Fall 2020 By Carribean Fragoza -

Text And Photographs

Summer 1972 By Joseph Epes Brown -

Pictures

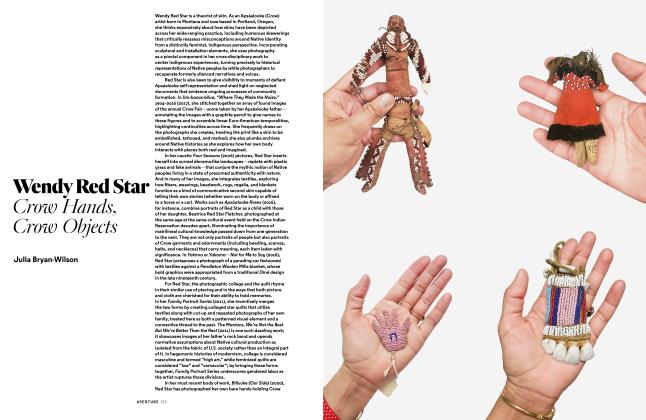

PicturesWendy Red Star

Fall 2020 By Julia Bryan-Wilson -

Words

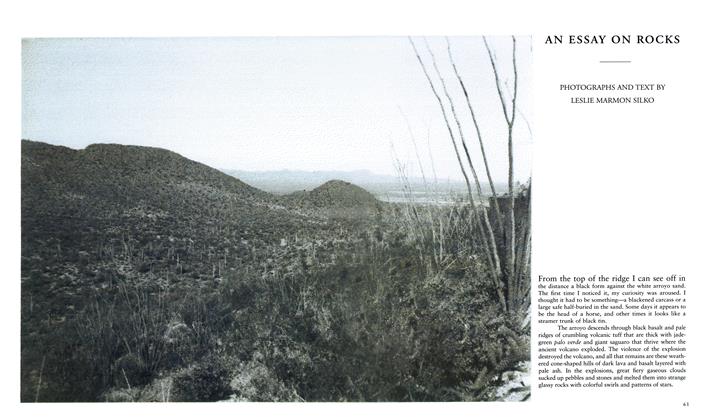

WordsAn Essay On Rocks

Summer 1995 By Leslie Marmon Silko -

Words

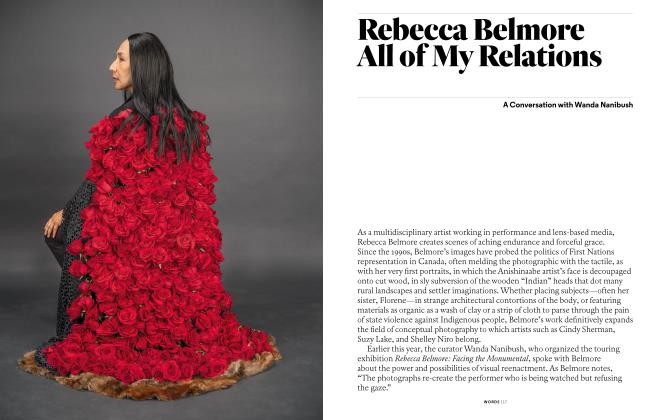

WordsRebecca Belmore: All Of My Relations

Fall 2020 By Wanda Nanibush -

Words

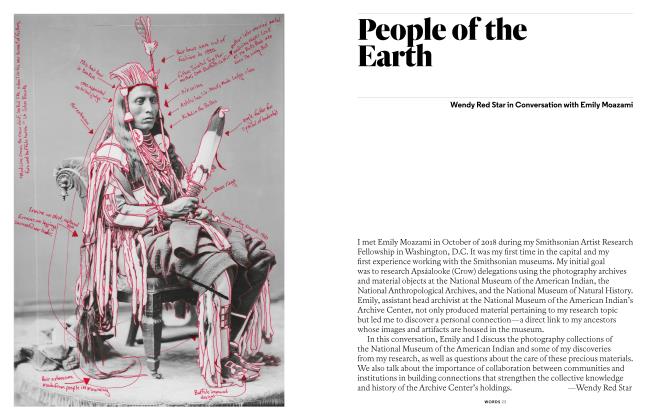

WordsPeople Of The Earth

Fall 2020 By Wendy Red Star