East 100th Street

Jonathan Green

Cambridge, Massachusetts 1970. Harvard University Press, 123 reproductions, 11 x 12 inches. $25.00 Paperbound $9.50. During 1967 and 1968, Bruce Davidson spent a great deal of his time photographing a single block in the East Harlem ghetto. Working with a large 4” x 5” view camera mounted on a tripod, film packs, and a strobe light, Davidson made over a thousand negatives. As the project progressed, he kept the photographic community informed of his work through occasional lectures illustrated with large lantern slides. In March 1968, Du magazine published a portfolio with text by Davidson, and on August 15, 1969, Life gave the project a four-page spread.

Since its inception, the Harlem Block Project has been the subject of sociopolitical controversy. While many of the extra-photographic issues raised deserve attention, their very legitimacy and the incomplete nature of the project has tended to obscure the photographs. Davidson’s final selection of 123 images has been presented in a brilliantly printed volume published by the Harvard University Press. In this volume, personally supervised and edited by Davidson, we have a further opportunity to examine the photographs.

The Place We enter Davidson’s world through the image of the street. Set alone, unpaired —as no other image in the volume —the first photograph takes on a weight and significance that permeates the entire book. Set before us, spilling out of the frame and piling up at our feet, is a world that draws us in as much by vertigo as by desire. It is a heavy world of hovering silence: a canyon world, distorted by wide angle perspectives and dark tonalities. While a few lone women do move slowly down the endless sidewalk toward the light, the only real motion is the movement of the street itself. Unyielding, uncompassionate, the pavement like liquid asphalt drifts up over the sidewalks and the slanting racked buildings, weeping over all in its path, threatening to inundate and engulf an entire world. In its movement it darkens the figure in the decaying doorway. Leaning back into the darkness, hands deep within his shining leather jacket, his invisible eyes burn us with their concern.

Intimating anticipation and change, the image itself, unbalanced, leans forward from its frame. It is the end of autumn. Summer’s ice cream sticks and hopscotch squares float upon the surface of the street. The voice of playing children has been silenced. Sound is only a memory as mute as the human figure outlined by dust and litter in the sidewalk cracks. The year is turning slowly toward seasonal death.

As we turn the pages of the book, expectation of change is thwarted. The year will not die. There is no spring or fall, dawn or dusk. Neither is there any intrinsic distinction between night and day. Time and the seasons have bypassed the world of East 100th Street. The unspoiled light which could carry the vigor and essence of growth and momentary change has been banished. No pure light floods this world. What daylight does seep through the windows is so diminished by weather and alleyways that it frequently appears even dimmer than the sorry electric lights of the tenement rooms. Neither is there any sound or movement in this world. The juke boxes and record players, so visually conspicuous, have been muted in dark tonalities. The movement of dancers and musicians has been frozen by a deceptive and passive illumination.

As we move from image to image, the very air of the photographs takes on a physical and emotional weight. Space is palpable; it is heavy and ominous in the palm of your hand. It is as close as breathing, as real as touch. With seemingly inexhaustible strength, the same formal, slightly unbalanced space revealed in the first image becomes a presence, a measured weight in hallways and in darkened rooms.

In these images the depth and weight of space are created not only by a wide angle vision but also by a dark, nearly opaque, vertical tone that is transformed by its repetition from being merely the color of the endless pavement into the emotional coefficient of Davidson’s world. For Davidson, the preponderance of shade over light has become a metaphysical statement on the human condition. The essence of his world is told in the patterns of dark and light long before the details of each image are defined.

Squint your eyes as you look at the 13th image. As the subject becomes unrecognizable, the meaning is revealed in the remaining chiaroscuro of the print. In this plate we come upon a child seemingly pressed upon his bed by the overpowering weight of a forgotten room. As if attempting to dispel the gloom, the rays of a bare, indifferent, and unreachable light bulb pick out a feeble highlight on the wall, the doorway curtains, and the child’s gown. Yet, the highlights reveal only an empty scar, the curtains lead to total darkness, and the child’s gown is starched and wrinkled like a shroud of death.

Darkness and light compete in the architecturally and emotionally equivalent bedrooms of the 9th and 109th images. In each, the windows have become barriers to the light. In the 9th image long flowered curtains, presided over by Christ, withhold and absorb the natural light. In the 109th, old dishtowels and shade defeat both light and air.

These images represent only the first stage in the disintegration of the natural balance of shadow and light. In the 61st image, a heavy vaporous darkness floats up from the floor and begins to obscure the room. A child, little more than a shadow, peers out at us from behind sheer curtains while a face shimmers on the television screen. Isolated by the very darkness, everyday details —the arms of the antenna, the clock in the shape of a metallic star, the piled newspapers, and a Time magazine — stand out in cold precision. We are shocked at how quietly modernity, with all its inhumanity, has arrived in this dark tenement room. In the 101st photograph, black and white have ceased to coexist; and the image is given over to the mysteries of near darkness. A glowing jukebox floats in space and barely illuminates the outline of a woman. Before, space had texture and substance; now it has only tone and weight, a darkness absolute and impenetrable.

The cumulative effect of darkness in Davidson’s world is reinforced by both the format and presentation of the photographic images. Previously, in Du and Life a variety of sizes and placement added vitality to the presentation of the plates. In the book each plate is printed exactly the same size whether vertical or horizontal; each is insistently centered on the page. There is no meaningful tonal change from one image to another; each has the same weight. No rhythm or progression is developed. We are left with a sense of unbreakable uniformity. It is a world that contains no exits, no potentials for escape.

The tragic sense of the book is unrelieved. Even the few images that tell of hope, pride, and youth are overshadowed. Taken alone, the 11th plate, the nude young mother and child, embodies the possibility of growth. Both warmth of human affection and the brightness of simple silver jewelry break through the darkness. Black becomes truly beautiful; nevertheless, its hope is quickly extinguished. The next page shows a prison-like wall of a decaying tenement which is followed by the depressing picture of a child huddled close upon his bed. With the turn of a page, youth and innocence have been swallowed by the same dark atmosphere of the street with which the book began.

It is not photographic capriciousness that has caused East 100th Street to be rendered so dark. It seems to me that the photographer has been captivated by historically and psychologically determined symbolism. Black and white have long been emblematic of the polarities inherent in human perception. While, in reality there are no such absolutes, light and darkness have come to imply the extremes not only of natural properties but of moral, psychological, and theological qualities. These two abstractions have the power to summon such opposing principles as knowledge and ignorance, id and ego, hope and despair, the Devil and the Divine. Whatever conditions the mind can conceptualize as negative and horrifying have become linked with the idea of blackness. In its most dehumanizing aspects, this polarity has helped mold a white racism in which the attributes of blackness have been extended to the black man himself.

At the same time such fantasies of race have developed, an aesthetic has evolved which equates darkness and mystery with insight and profundity. The extolling of darkness mirrors civilized man’s attempt to escape from over-reason by returning to the depths of aboriginal knowledge and primordial fecundity. It also indicates man’s fascination with the forbidden, his reaching for the distant and shadowy places of the world and self where perhaps the real power lies.

Davidson’s book suggests these interpretations of black and white. The sense of blackness with which it is imbued stems from Davidson’s awareness of the spiritual impoverishment of our chaotic urban culture and the deathin-life existence of the block’s inhabitants. Yet, the shadows may also represent unconscious projections of a latent racism that each contemporary American harbors on some level within his psyche. Paradoxically, the darkness of the presentation may suggest to the photographer’s audience profundity and artistic excellence.

The People While the space of these images is dominated by symbolic blackness, the people are not abstractions: They enter the photographs clothed in their own specificity. Davidson has come to intimate terms with the physical world of East 100th Street. Space has been confronted, assimilated, and abstracted to its essential emblematic nature; nevertheless, the people who inhabit this world are irreducible. Urban reality and cultural failure have stripped them of the veneers of luxury and the trappings of society. They have been pared down to their essential humanity. While their world may be rendered in terms of the darkness of spiritual entombment and symbolic crucifixion like the cover picture, the people remain the greater mystery.

We come upon the inhabitants of the block in the 3rd plate. Like the first image of the pavement, this photograph, because of its early placement and inherent power, helps to generate the meaning of the entire book. We are met, first of all, with eyes: the dark window-eyes of the building and the cold, silent, impenetrable eyes of the people. There is no communication here. The music that a moment before must have been bursting from the stereo speakers has been hushed by our intrusion. In Du, Davidson published a version of this image made at a slightly different moment from the same camera position. In that image Davidson allowed one of the men to look out of the frame away from the camera and the viewer. Here Davidson insists that our presence be acknowledged. And this insistence has created a moment of suspended animation: a moment of excruciating consciousness in which the people are pulled out of their time and place, turned toward us, and forced to focus all their brooding energy.

Davidson has chosen to release the shutter at the moment of heightened awareness of photographer and subject for each other. This moment is not generated by the spontaneous meeting of eyes but by an intense commitment on the part of the photographer to know and an equally intense resolution on the part of the subject to remain unknown. The tension that results is often unbearable. This extreme opposition of wills is revealed in the very muscular tautness of the 3rd image as well as in the images of the derelict kneeling in the abandoned subway entrance (28), the half-dressed teenage couple (75), and the young black holding an open switchblade knife (73). The woman’s defiant flaunting of her bare breast in the 94th plate and the stance of the woman in the 103rd only intensify their inaccessibility. While these images may be extremes, the opposing wills of observer and observed pervade the book. In all these images the sense of intrusion is primary.

Rather than seizing upon life as it presents itself, Davidson has carefully arranged before the camera a series of cold, frozen moments: a series of stilllifes in which people look at each other over an unbridgeable abyss. The formality of eye contact has only brought separation. Instead of intimacy we have intrusion; rather than contact we have confrontation. This paradox is further heightened by Davidson’s wide angle vision which gives us the curious experience of being physically close yet emotionally distant. Again and again we are brought face to face with people we cannot really know. Oppressed by the space, frequently obscured by the darkness of their world, and inhibited by the photographer’s presence, they have buttressed themselves with a wall of invisible armour that ultimately keeps us apart. It is precisely at this moment that we become acutely aware of their individual humanity. For it is our inability to bridge the abyss that makes us so painfully aware of the sensibility on the other side. Have they not acted as we would have acted —self-conscious, uncomfortable, at times defiant or withdrawn? Is not the fear we feel a testament to our own isolation? Behind the masks of sadness and of joy, behind the slack and tightened lips, behind the sometimes hostile, sometimes happy, sometimes uncomprehending eyes we recognize ourselves.

Only perhaps in two instances does Davidson allow the symbolic world to totally overpower the reality of the inhabitants. In both of these it is Death — that essential underlying presence of the book —that becomes visible. In the 113th image we see a woman filling her basket of clothes at an all-night laundromat. The clothes dryers behind the hooded woman seem to become ominous ovens and dark portholes to another world. In the 83rd plate we come upon a man, strongly backlit, in his somber room. Humans or apparitions? We are not sure. For here the darkness and strangeness of the place have diminished the particularity of the people. The man stands wearing what could be the dark robes of a satanic priest, a smooth ebony mask hangs on the wall above his head, and a turbulent bed rages at his side. This extreme sense of unreality is rare in the book. Most often we are left with real, though remote, people in a half real, half symbolic world.

An Evaluation It is understandable that a book whose subject is as emotionally and politically charged as East 100th Street should elicit a great deal of comment and controversy. Davidson has been accused of exploiting a repressed subculture, and he has been praised for revealing the exploitation of an entire people. The photographer’s comments on his personal involvement in the block have been considered statements of intent and held to be rigorous prescriptions for the images. The burden of this criticism has been the sociological and political significance of the book and its success or failure as a source of political action. Such attitudes may be seen in A. D. Coleman’s and Philip Dante’s reviews which were published simultaneously in The Neiv York Times on October 11, 1970. Both articles revolve around one of the thorniest problems facing the contemporary social photographer, his relationship to his subject. Yet Coleman’s and Dante’s concentration on the extra-photographic makes it impossible for either to accept the actuality of the images. Both critics are victims of the camera-cannot-lie syndrome. Coleman perceives the block as a place of “squalor and degradation” and thus is horrified when Davidson presents aesthetically pleasing images. Dante perceives the block as a soulful community that partakes of joy and beauty as well as squalor and ugliness, and he is angered by the concentration in the photographs on “a dark journey into purgatory.” Coleman confuses the formality and craftsmanship of the execution with meaning and neither he nor Dante are able to distinguish the actions surrounding the act of photographing from the images produced. Ironically, the political qualities Coleman demands are those which Dante condemns. “Photographers are going to have to abandon their concern with Art and Beauty and start making stark, grim, ugly, repulsive images,” Coleman writes. Yet these qualities are profoundly present in the attitudes implied in the images. Coleman cannot see these attitudes for his socio-political emphasis obscures the symbolic nature of the book. Dante, who actually reads the images quite closely, cannot accept them for they lack truth to subject. Neither writer realizes that the reality of the photographs is not the actuality of the block but the reality of Davidson’s perceptions.

Davidson was not working as a photo-journalist or sociologist; he was not attempting to record with absolute fidelity the reality of the block; nor does he appear to be working in the documentary tradition of Lewis Hine, Dorothea Lange, and Walker Evans. Davidson’s images are not primarily meant to reveal the wrongs done to the people of East 100th Street nor to motivate the viewer toward social protest; rather, Davidson, like Strand, has constantly used people from various lands and cultures as the basis of a highly personal and subjecdve art. His conception of the medium forces him to find the raw material of his craft in external reality. For Davidson reality has become merely the touchstone through which he is able to crystallize his own perceptions of the human predicament.

Nevertheless, Davidson’s work in East Harlem was not without political significance. “I have come away with much more than photographs,” Davidson wrote in Du. No one who has heard Davidson speak or who has carefully read the texts in Du and in East 100th Street will doubt the sincerity of this affirmation. While the photographs record little of this involvement, Davidson was warmly received into the life of the block and made a series of mutually fulfilling relationships with many of the people he worked with and photographed. It is not unusual for a man to photograph out of one part of himself while he relates out of another. Davidson’s social objective was quite different from his aesthetic; both seem to have been equally nourishing. The interpersonal communication and expanded human awareness that he pursued, albeit somewhat naively, not only suggests one direction of social change but possibly helped to implement change by actual human contact.

A photograph is constructed out of the dialectic of perception and projection. Though the information it holds mirrors the objectivity of the eye, this information is structured by the subjectivity of sight. For each act of perception implies taking a position and is a unique projection of sensibility and consciousness. When we look at a photograph, we look at the world quite literally through someone else’s eyes. Thus it is not uncommon to feel in the photograph the personality of the beholder as well as the actuality of the subject beheld. A photograph, then, becomes the sum of the objective world and the photographer’s vision. The least successful of Davidson’s images point to only one side of this dialectic, either the photographer’s subjectivity or the subject’s cold reality. The finest images in East 100th Street intensify and integrate both poles of the equation. Through a strong grasp of the reality before the camera and an equally strong sense of the metamorphosing quality of the medium, Davidson has produced images that transcend the immediacy of the block: images that convey human isolation and the power of darkness.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Photographs Of Peru

Spring 1971 By John Cohen -

Photographs of the Xicrin Indians of the Amazon Basin

Spring 1971 By Professor Reichel-Dolmatoff -

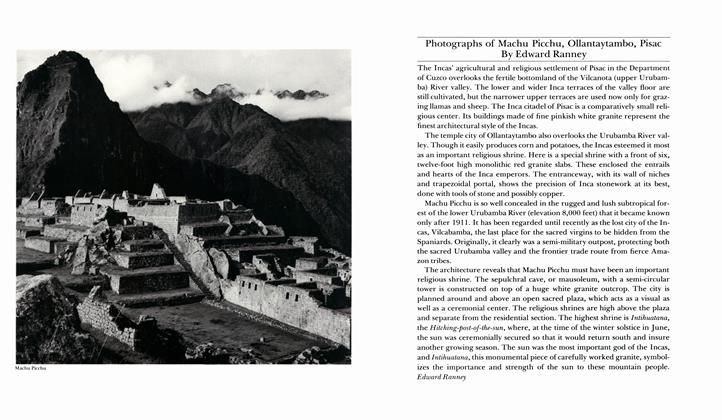

Photographs Of Machu Picchu, Ollantaytambo, Pisac

Spring 1971 By Edward Ranney -

The Real Treasure

Spring 1971 -

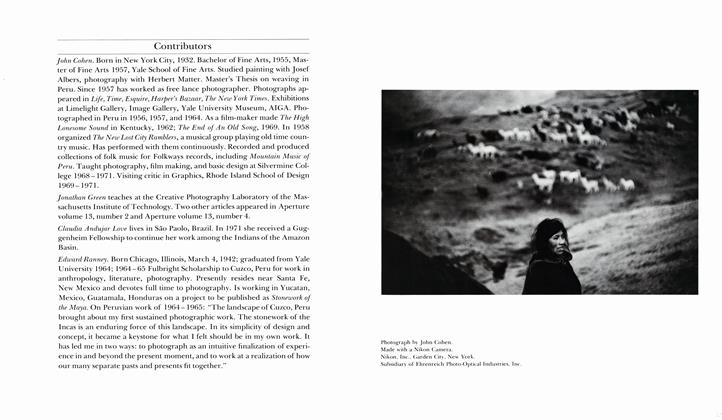

Photograph By John Cohen

Spring 1971 -

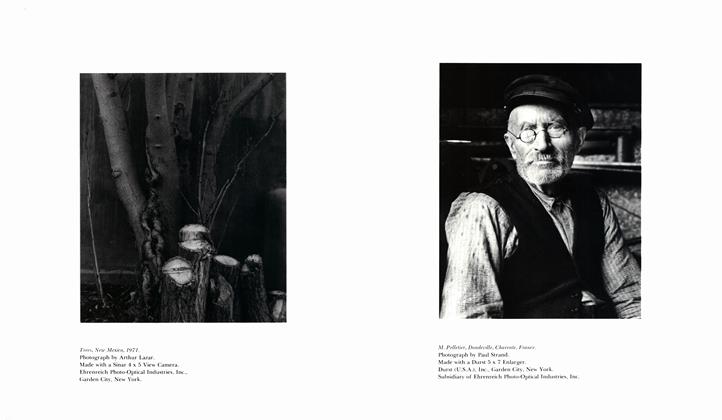

Trees

Spring 1971

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jonathan Green

-

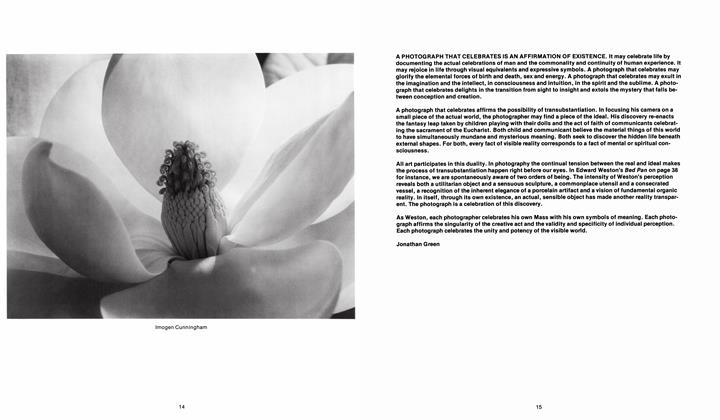

A Photograph That Celebrates Is An Affirmation Of Existence

Spring 1974 By Jonathan Green -

Introduction

Fall 1974 By Jonathan Green -

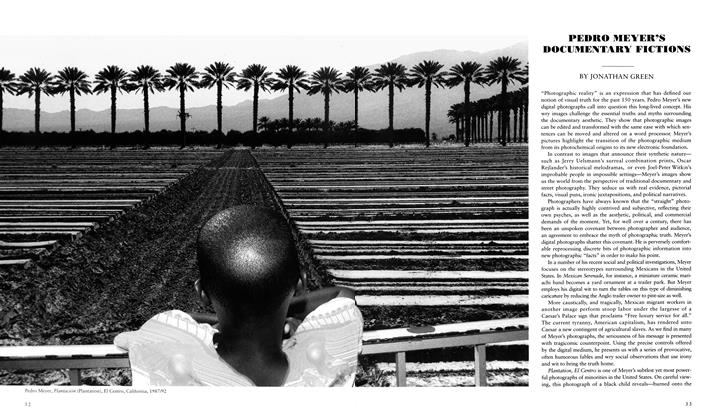

Pedro Meyer's Documentary Fictions

Summer 1994 By Jonathan Green -

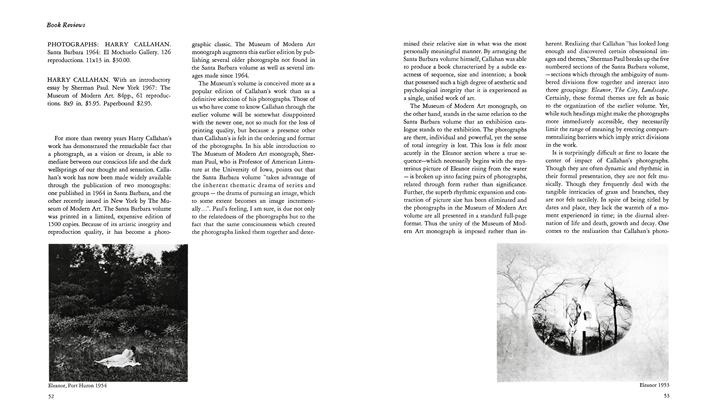

Book Reviews

Spring 1968 By Jonathan Green, Minor White -

Comment And Review

Summer 1967 By Peter C. Bunnell, Frederick D. Leach, Jonathan Green, 1 more ...