MISSISSIPPI DELTA PHOTOGRAPHY

REVIEWS

The Mississippi Delta has been called “the most Southern place on earth.” A swampy, heavily forested wilderness with a history of extreme wealth and equally extreme poverty, of bountiful hospitality and racial oppression, of palatial plantations and sharecropper shacks, the Delta offers a concentrated collection of most of the basic tropes of Southern culture.

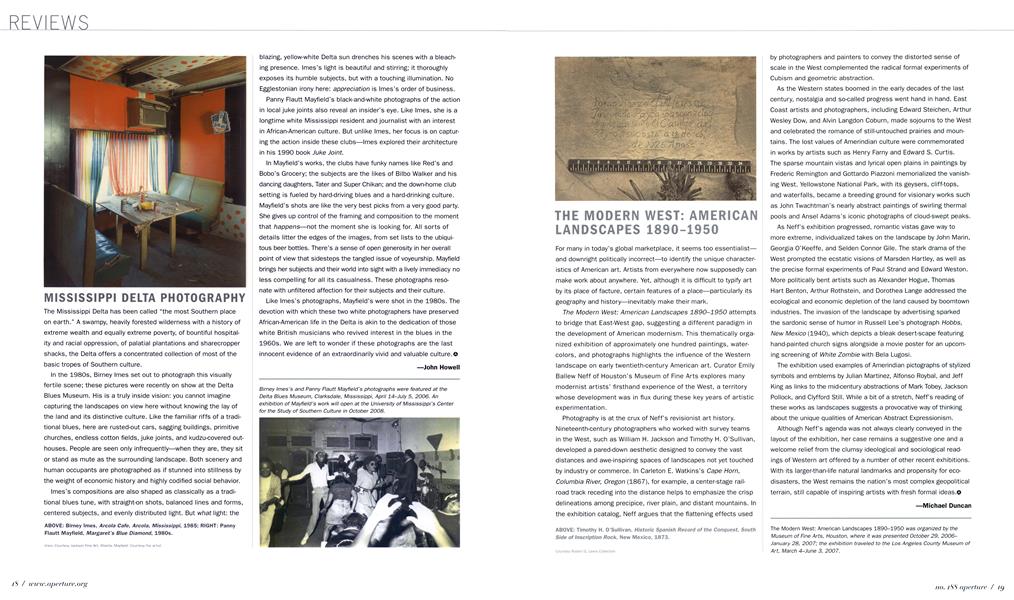

In the 1980s, Birney Imes set out to photograph this visually fertile scene; these pictures were recently on show at the Delta Blues Museum. His is a truly inside vision: you cannot imagine capturing the landscapes on view here without knowing the lay of the land and its distinctive culture. Like the familiar riffs of a traditional blues, here are rusted-out cars, sagging buildings, primitive churches, endless cotton fields, juke joints, and kudzu-covered outhouses. People are seen only infrequently—when they are, they sit or stand as mute as the surrounding landscape. Both scenery and human occupants are photographed as if stunned into stillness by the weight of economic history and highly codified social behavior.

Imes’s compositions are also shaped as classically as a traditional blues tune, with straight-on shots, balanced lines and forms, centered subjects, and evenly distributed light. But what light: the blazing, yellow-white Delta sun drenches his scenes with a bleaching presence. Imes’s light is beautiful and stirring; it thoroughly exposes its humble subjects, but with a touching illumination. No Egglestonian irony here: appreciation is Imes’s order of business.

Panny Flautt Mayfield’s black-and-white photographs of the action in local juke joints also reveal an insider’s eye. Like Imes, she is a longtime white Mississippi resident and journalist with an interest in African-American culture. But unlike Imes, her focus is on capturing the action inside these clubs—Imes explored their architecture in his 1990 book Juke Joint.

In Mayfield’s works, the clubs have funky names like Red’s and Bobo’s Grocery; the subjects are the likes of Bilbo Walker and his dancing daughters, Tater and Super Chikan; and the down-home club setting is fueled by hard-driving blues and a hard-drinking culture. Mayfield’s shots are like the very best picks from a very good party. She gives up control of the framing and composition to the moment that happens—not the moment she is looking for. All sorts of details litter the edges of the images, from set lists to the ubiquitous beer bottles. There’s a sense of open generosity in her overall point of view that sidesteps the tangled issue of voyeurship. Mayfield brings her subjects and their world into sight with a lively immediacy no less compelling for all its casualness. These photographs resonate with unfiltered affection for their subjects and their culture.

Like Imes’s photographs, Mayfield’s were shot in the 1980s. The devotion with which these two white photographers have preserved African-American life in the Delta is akin to the dedication of those white British musicians who revived interest in the blues in the 1960s. We are left to wonder if these photographs are the last innocent evidence of an extraordinarily vivid and valuable culture.©

John Howell

Birney Imes’s and Panny Flautt Mayfield’s photographs were featured at the Delta Blues Museum, Clarksdale, Mississippi, April 14-July 5, 2006. An exhibition of Mayfield’s work will open at the University of Mississippi’s Center for the Study of Southern Culture in October 2008.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Dialogue

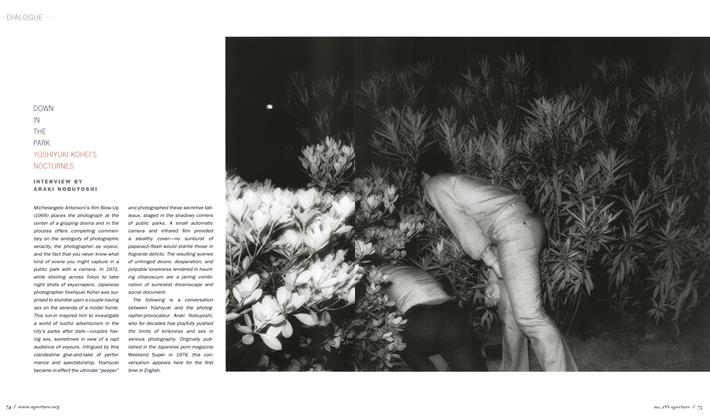

DialogueDown In The Park: Yoshiyuki Kohei's Nocturnes

Fall 2007 By Araki Nobuyoshi -

Essay

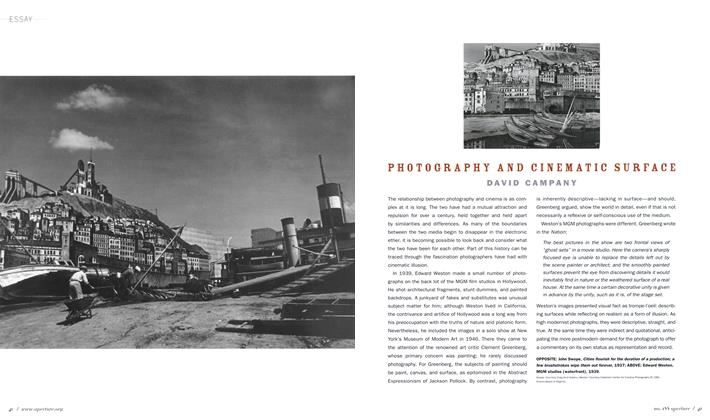

EssayPhotography And Cinematic Surface

Fall 2007 By David Campany -

Before The Lens

Before The LensRichard Avedon And Lee Friedlander: One Day In May

Fall 2007 By Jeffrey Fraenkel -

Witness

WitnessMikhael Subotzky Inside South Africa's Prisons

Fall 2007 By Michael Godby -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessWords Words Words: Photographs By Shannon Ebner

Fall 2007 By Lisa Turvey -

On Location

On LocationIsraeli Reserve Soldiers

Fall 2007 By Jeffrey Goldberg

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

John Howell

-

Profile

ProfileSight Unseen In Plain Sight

Winter 2001 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsChic Clicks

Spring 2003 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsFashioning Fiction In Photography Since 1990

Fall 2004 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsArtist To Icon: Early Photographs Of Elvis, Dylan, And The Beatles

Winter 2005 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsRichard Prince: Spiritual America

Spring 2008 By John Howell -

Reviews

ReviewsCharles Atlas: Joints Array

Spring 2012 By John Howell

Reviews

-

Reviews

ReviewsCindy Sherman Inside And Out

Spring 2004 By Adriana Marques -

Reviews

ReviewsRudy Burckhardt And His Friends

Spring 2001 By Douglas Dunn -

Reviews

ReviewsUta Barth

Spring 2012 By James Yood -

Reviews

ReviewsLight Years: Conceptual Art And The Photograph

Summer 2012 By James Yood -

Reviews

ReviewsPhotography And The Self: The Legacy Of F. Holland Day

Summer 2007 By Laurie Dahlberg -

Reviews

ReviewsJeff Wall 1978-2004

Spring 2006 By Susan Bright