COMMENT AND REVIEW

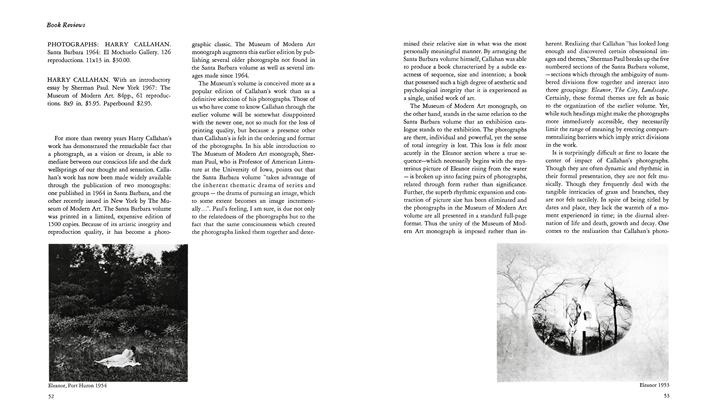

TIMOTHY O'SULLIVAN: AMERICA'S FORGOTTEN PHOTOGRAPHER. By James D. Horan. New York, 1966: Doubleday & Company, 334 pp., 343 reproductions of O'Sullivan's photographs plus documentary illustrations. 1114 x 83A in. $15.00.

T.H. O'SULLIVAN PHOTOGRAPHER. By Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, with an appreciation by Ansel Adams. Rochester, 1966: George Eastman House in collaboration with the Amon Carter Museum of Western Art. 48 pp., 40 reproductions. 8 x 8V2 in. $2.00.

Documentary photography cannot be exempted from the intimate relationship of history and style. The tragedy which has befallen us today is that the remnants of the immediate past most conveniently saved are old photographs. An image no thicker than a sheet of paper has come to represent the enormity of any object or event, and this miraculous advance in sophistication has allowed the photograph to be seen in terms of two dimensions standing for three, a variety of grays standing for colors and picture size representing life size. Thus there is the urge so often found with publications of this kind to view these documents of an external world with a respect altogether undeserving in such critical appraisal. It is a pity because it is an indication that what has happened is a separation of nineteenth century documentary photography from the interrelationship of history and style in favor of the exclusive and sentimental province of history alone. This is the case with three authors’ views of the photography of Timothy H. O’Sullivan (1840-1882).

James D. Horan is a journalist with an eye to the saleable and to the popular taste for photographs of the past. His book should be considered in terms of reportage, for his prose has the uneven flow of many newspaper articles and is filled with literary embellishments which are both bland and quixotic. A more skillful weaving of a briefer text with a more professional and visually oriented layout of the photographs could have eliminated much excessive verbage, though admittedly making for a less pretentious volume. This is especially the case in the first part of the book where we are given what in substance is a condensation of Horan’s previous work on Mathew Brady and a history of photographic processes. But by the sequence of its presentation the latter is not adequately clear for the reader with a non-photographic background nor accurate enough to please even the most broadminded photographic student.

Horan is forced to embrace many others in order to give life to this near phantom photographer. By virtue of the paucity of facts directly relating to O’Sullivan and in attempting to make of the photographer an “artist,” Horan commits the familiar mistake of expanding the mystery hy reflection rather than simply stating the known facts and placing the primary emphasis on the photographs. The intermediate approach to O’Sullivan in kind and quantity would seem to lie somewhere between Horan’s book and Beaumont and Nancy Newhall’s handsome but slight exhibition catalogue, which is more to the point though the essay lacks substance and the photographs have not been rigorously selected. The real issue then is to have a monograph which is concise in word and doubly expansive in photographs as those included in the exhibition catalogue. Similarly, this hypothetical author must strive for at least the quality of reproduction in the Newhalls’ catalogue because Horan’s reproductions are altogether lacking in any sensitivity ; in fact, in any relationship to the originals.

In general there are few specific factual items to challenge directly for there is little doubt that Horan was thorough in his research. Indeed two of the soundest features of his hook are the notes and bibliography. There remains, however, something strangely tentative about certain facts. For instance, Horan gives O’Sullivan’s birthplace as Ireland (a fact given first not in the text but in footnote three on page two and then mentioned in passing in the text on page twenty-two), though the Newhalls give New York City. Undoubtedly the Newhalls’ source was O’Sullivan’s 1880 application questionaire for the position of Chief Photographer for the Treasury Department which is reproduced on page three hundred and fourteen in the Horan book. Horan in reproducing this document fails to call attention to the fact that O’Sullivan therein, and in his own hand, listed New York City as his place of birth. This alone casts doubt on other of Horan’s assertions, as well as his somewhat excessive use of adverbs and adverbial phrases such as, “perhaps,” “undoubtedly,” “evidently,” “must have been,” &c.—all being known hazards in writing this kind of biography.

In addition Horan allows ambiguities in his treatment of Mathew Brady. Apparently in his drive to give O’Sullivan deserved credit as an individual photographer Horan somewhat pre-maturely blinds Brady and places him in the throes of indebtedness and self-doubt. This issue is raised only because there are discrepancies between statements early in the book and those later on regarding Brady’s activity and the relationship to his assistants, former assistants and colleagues as well as the fact that Horan in his biography of Brady (1955) attributes photographs to him through at least 1871 and even into the early 1880’s. The Newhalls correctly place their emphasis on O’Sullivan without depreciating Brady’s influence early in the career of the former. Unfortunately there remains disturbing conjecture as to precisely what Brady’s role was between 1861 and 1865 even after the publication of Roy Meredith’s Mr. Lincoln’s Cameraman (1946), Horan’s own book, Beaumont Newhall’s The Daguerreotype in America (1961) and now this book. Perhaps a thoroughly stylistic examination of the work of many of the photographers then active would yield some refreshing clarity without a cause célebre for any one of them.

Finally, there is too much narration of period history, for instance Horan’s details of the scientific exploration of the American West could more profitably be gained by reading the works of William Goetzmann among others, and too superficial a concern for the interpretation of the photographs and their aesthetic and stylistic quality. Horan describes the “chilling mist’’ felt in the “Harvest of Death’’ photograph of the Gettysburg battlefield on the morning of the second day of fighting, though one might readily question the existence of the chilling mist on a July morning and from the shadows the time appears more nearly noon under a clouded sky than early in the day. Subtle details missed throughout characterize this book. And this, in the final analysis, is Horan’s general weakness.

Subtle awareness is not so lacking in the Newhalls’ coverage ; and a hint of what is the significance of these images in point of fact and style may be found in Ansel Adams’ brief and personal appreciation. Horan directly, and the Newhalls implicitly, find O’Sullivan’s late photographs valuable to an understanding of the wildness, majesty and vitality of the American West. But nowhere is there a critical evaluation of the effect these photographs—as distinct from that of other descriptive media —had on the public attitude or on contemporary governmental action with regard to this portion of our landscape.

A photograph is not inevitably significant only because it was made under hazardous or particularly unpleasant circumstances. Generations of photographers and critics have used this kind of significance by proximity in an attempt to invest weak photographs with meaning. Many have been misled. This fact explains the fallacy of why photographers are generally poor judges of their own work, for they are really not selecting images but rather their personal experiences in taking the picture. We must concede that great art is produced only by individuals endowed with great creative gifts. Of all fantasies none is greater than the notion of the expressive artist in photography or any other medium as a capricious Bohemian fashioning his works in complete abandon. Few photographers have ever achieved lasting significance who were not, or did not make themselves in their lifetimes, supremely intelligent or even learned men. Now to suggest that a man is not necessarily a great photographer, as is the case with O’Sullivan, in no way depreciates the value of certain of his photographs. Rather it places the emphasis more correctly to the point at hand ; that the camera itself has given more than it received. Each of these authors attempts to make a truly significant photographer of O’Sullivan —apart from history. This is something difficult to do and untrue and it returns once again to the interrelationship of history and style—in which the facts thus presented will reap a greater harvest than either alone.

O’Sullivan’s photographs taken in breadth either as objects of utility or quality—history or style—are weak. In spite of their clarity and not withstanding the basic American propensity for clearness and fact they are not monumental. That is, there is no sense of order or containment of chaos. His Civil War photographs are practically non-committal. They cannot be called heroic, at least in the Greek sense of challenge, or pacific by showing the rotting dead or baleful fires of the battles. They are simply pathetic. Brady, who in Horan’s work comes off with somewhat less of a reputation that he even enjoys at present, did have an opinion of war to express and it was very near the Continental tradition of neo-classical heroics. He saw the melodramatic history picture as the pinnacle of nineteenth century academic art. Thus Brady undertook to depict and make something of the grand, human scope of the War in such manner as he had made something of portrait photography by placing it in the tradition and style of academic painting. But Brady understood something very significant about the time, which was the basis of his view of war and should be in part a basis of his position in the history of photography. It was that photography had brought the death blow to the noble, formal painting of the war myth and the mythic heroes of war. The photograph, which by virtue of very numbers and literalness, destroyed the concept of human grandeur as seen in the eloquent death of the few and replaced it with a view of war in all its final satanic gravity to every man. This is why today we think of the Civil War as a miserable war.

In the great canvases of the past there was the classical element of summation which Brady had recognized as only extraordinary in individual photographs; thus he chose the vast, massive documentation of a discontinuous nature to achieve grandeur and totality in scope—a distinctly modern form of summation and monumentality. The photographers of the Civil War, as earlier with Roger Fenton in the Crimea, were individually incapable of summarizing the over-riding act, the message, the comment even though each was an actor in the great drama. Thus we should herald Brady’s approach. The candid manner, the random pose of freely moving persons were particularly suited to the individual parts of this endeavor, as well as to the democratic nature of the times. Thus it is that Brady must remain an integral part of this period in the medium’s history.

O’Sullivan’s photographs, including those made after the War, are very much random images. Poignant subjects in some cases, but his pictures were not sustained by the greater vision of the imaginative artist or conceptual genius in photography. And this fits with the anonymity of his character and his life—one free moving young man, chipped from a rock and tossed about the country of wide spaces and significant only in the equal struggle for personal survival.

Limited in his vision, not trained to some of the elemental relationships of seeing, his photographs in these books show a record of missed opportunity to make of his often unique experience a significant photograph. His work does have definite highlights. The “Grant Council of War at Massaponax Church, Virginia” is one of the major photographs of the whole century and the fact that it was made by O’Sullivan in this context of limitation in seeing is all the more to the point in understanding the inherent characteristics of the camera in the medium of photography. Its structure, organization and the sense of sequential time by virtue of superimposition and blur are magnificent. The “Canyon de Chelly,” “Fredericksburg,” and the “Harvest of Death” are outstanding, but isolated.

With the publication of a monograph it becomes difficult to make of a picture-maker a photographer. When, as so often in the past, a few highly selected images were published significance could readily be obtained by omission. But in both new publications consisting of about three hundred and fifty of his photographs we see all and can come to the realization that in his hands the camera not the photographer was dominant. Thus I feel that O’Sullivan, throughout his imagery, came uncomfortably close to hitting forces he only in some degree managed to master.

PETER C. BUNNELL

PHOTOGRAPHERS ON PHOTOGRAPHY. Edited by Nathan Lyons. Englewood Cliffs, 1966: Prentice-Hall, Inc., in collaboration with George Eastman House. 192 pp., 62 reproductions. 9 x 6 in. $11.95. Paperbound edition, less photographs, $3.95.

Photographers on Photography is a collection of primary documents in the history of this art ; it appears in two versions and in two bindings. Both contain a series of essays by twenty-three photographers and a set of biographical and bibliographical notes. The hardcover edition is provided with 62 plates listed on an unnumbered page facing page 161, plates and list have been omitted in the paperback edition. The photographic material has been closely matched to the time span of the literary text, but extends the period covered by some seven years (1885-1966). In the hardcover version, all of the photographers speak in two media, literary and photographic.

While it is commonplace to say that we live amid a variety of images, photographic and otherwise, it should be noted that all of these images have one thing in common—their forms are fixed. In them, a passage of time has been frozen, whether that segment is a portion of a second or the record of the days and weeks necessary for the production of a painting, or etching—or even within the controlled and fixed time of the cinema. In every case, the fluid present has been crystallized in an image, a present which will be replenished out of a gaseous future. Whatever the points of view of the photographers included in Photographers on Photography, all their essays demonstrate an extension of the analogy included in the previous lines. If the photographic image is analogically relatable to a block of ice, as the fixed past to the liquid present, then the past has at least an amount of what the physicists would call, “residual entropy.” Thus, the artistic image, unchanging and rigidly crystalline though its form may be, still permits a movement through its interstices by means of this residue : after all, ice is less dense than water. These photographers, using the literary medium, demonstrate the fact that their images are means to an immediate and present involvement with a still living past. When images lack this immediacy and preclude this involvement, they are not art ; when they possess, or accommodate it, then photographers and others may use them to re-explore, literally re-live, an experience that has ceased to exist in its primary form. Strangely enough, the photographer, and his medium, are today quietly defining history in John Dewey’s terms, “All historical construction is necessarily selective. And . . . everything in the writing of history depends upon the principle used to control selection.” 1

I acquired the paperback version of this book as soon as it appeared in the stores ; I found it quite rewarding but something less than pure joy. I was then sent the hardcover edition, and finished my reading in it. I can only attribute my extreme satisfaction with the latter to the fact that I had a ready access to the photographs which it contained.

This contact with the immediacy of the image is precisely the point which the various photographers from Henry P. Robinson and Peter H. Emerson to Minor White, in different ways, attempt to make clear. By accident. I became a clear demonstration of the validity of this aspect of the essays ; photography, like any other art, is not justifiable as photography, in another medium. Photography as philosophy can be justified in literary form ; it frequently is and with eloquence in the text of this book. But photography is to philosophy as the subject is to its photograph; the latter is an abstraction based upon the former. There is a necessary sequential order involved. First, there is the subject, second the photographic image, third the philosophy. One should realize, in passing, that this sequence does not necessarily imply a hierarchy of value.

The photographers, speaking on the subject of photography, produce explanations of images which are themselves explanations of subjects/situations. All twenty-three authors, in their literary efforts, utilize the same subject-matter, e.g. photography. Each one presents, not the explanation, but an explanation of the principle of controlled selection. Their explanations vary as their photographs vary, and for the same reasons. Between Peter H. Emerson’s subject-matter for the photograph, Rushy Shore, 1886, and that image, stand both the man and a considerable technological array.

Between that image and Emerson’s literary statement, once again the man is interposed. It is the nature and the import of this interposition of the man that is defined by this book. Emerson the photographer and Emerson the essayist share many things, hut they are not precisely the same person ; possibilities open to one are closed to the other. Essays are not photographs, though each may inform the careful reader/viewer of the other.

The user of Photographers on Photography should realize that he is in possession of both work and its subject-matter, essays and photographs; this is a position occupied with difficulty relative to any other visual art. The cogency of Moholy-Nagy’s statement, “The illiterate of the future will be ignorant of the use of the camera and pen alike,” is made abundantly clear, and a remedy presented. And if the user of the book seeks more than Moholy-Nagy’s implicit revelry amidst technological wonders, let him turn to the refreshingly explicit pragmatism of Henri Cartier-Bresson. “It is enough if a photographer feels at ease with his camera, and if it is appropriate to the job which he wants to do.” Cartier-Bresson’s essay becomes a re-echoing of Dewey’s principle of selection. It is the variation on the concepts of the “jobs they want to do” and how they describe them, that makes this collection mandatory reading.

FREDERICK D. LEACH

I. Dewey, John, “Historical Judgments,” The Philosophy of History in Our Time, Hans Meyeroff, Ed. New York, 1959, p. 167.

THE DAYBOOKS OF EDWARD WESTON: CALIFORNIA. Edited by Nancy Newhall. New York, 1966: Horizon Press in collaboration with The George Eastman House. 290 pp., 40 reproductions. 10 x 8 in. $15.00.

The first volume of The Daybooks (Mexico, 19231927) was published in 1961. Now, after an interval of more than five years, the Horizon Press in collaboration with The George Eastman House has published the second and concluding volume of Edward Weston’s journal: The Daybooks, Volume II, California. This book covers Weston’s entries from 1927 to 1944. Like the first book, this handsomely printed volume contains forty photographs which represent Weston’s work of the period : Shells and Peppers, Point Lobos, Portraits and Machines, and Landscapes and Nudes.

The Daybooks of Edward Weston powerfully testify to Weston’s eminent sanity and to the sense of wonder which lay at the basis of his life and art. Weston’s photographs are, of course, an even more eloquent record of this special awareness and honesty. Yet the Daybooks are sufficient to reveal that this sense of wonder was the source of his creativity and that it made itself known in all areas of his life. It is seen in his concern for form, in his interpersonal relationships, and in his attempt to verbalize the sense itself in a theory of the essential unity of all things.

The Daybooks give us an insight into the nature of Weston’s wonder—“amazement” was his term for it— by documenting the process by which he assimilated his environment. In spite of the enormous tenaciousness Weston displayed when dealing with any single photographic problem, the Daybooks would indicate that his “amazement” was a quality of passive openness. The subjects of his photographs—as his loves—came to him willingly ; rarely was there any directed search. Rather than searching, Weston waited :

I always work better when I do not reason, when no question of right or wrong enters in,—when my pulse quickens to the form before me, without hesitation nor calculation.

When his response came immediately and without premeditation, he could work “with real ecstasy” and he knew that such work would possess the vitality of his perception.

This manner of perceiving was essentially photographic: Weston’s camera became an extension of his way of seeing and Weston became an extension of his camera :

I take advantage of chance—which in reality is not chance—but being ready, attuned to one’s surroundings—and grasp my opportunity in a way which no other medium can equal in spontaneity, while the impulse is fresh, the excitement strong.

In photography—the first fresh emotion, feeling for the thing is captured complete and for all time at the very moment it is seen and felt. Reeling and recording are simultaneous.

Weston, as his camera, possessed the ability to remain open to the shiftings of reality—to be constantly aware of the present moment—and then, in an instant, to capture and transform that shifting present into stable form.

In Weston’s desire to “live and work, fully” he attempted to enter into relationships—whether with an object, a landscape, or a human being—with total involvement. In the chaos of daily living such total involvements were rare. Yet when such an experience came, Weston knew he could extract from it the force needed for creativity :

B. danced for me ! This time I was spectator,—not photographer. A definite feeling is not always easy to put down in definite words, but I know I was privileged to have her dance for me,—to me. The work I do today must be finer than that of yesterday because of B. dancing : she has added to my creative strength.

Even the inanimate objects Weston photographed became a part of his being. The peppers, cabbages, and fruit were the foods that roused the delight of his mind and eye as well as satisfied the needs of his body. So too the nudes he photographed were his lovers and friends, individuals with whom he had shared the wonder of communication and delight. Indeed, the intense selfcenteredness and self-conceit which the Daybooks frequently display is due to the fact that Weston’s world was built around the principle of involvement ; the involvement of his whole being in the things of the universe. For the dialectic of subject and object was the continual basis of his self-concern : Weston had sufficient egoism to understand his place in the universe and sufficient wonder to transform that understanding into form.

The writing of the Daybooks played an important part in allowing Weston to retain the openness he needed for his “amazement.” It gave him a legitimate, expressive outlet for his fears, hostilities, and “petty personal reactions.” It acted as a cathartic which enabled him to “cleanse the heart and head—preparation to an honest, direct, and reverent approach when granted the flash of revealment.” It also provided a catalyst for meditation and introspection : the writing offered a moment for review, consolidation, and affirmation. At times one even has the feeling that the words written were not as important as the act of writing itself, or as important as the very quietness which surrounded the moment when the entry was made : Peace again !—the exquisite hour before dawn, here at my old desk . . . seldom have I realized so keenly, appreciated so fully, these still, dark hours.

Besides giving us insights into Weston’s own character, the Daybooks provide a fascinating account of the state of photography as a “fine-art” in the twenties and thirties. In Weston’s attempt to understand the society about him, he dealt with the attitudes of the public and other artists toward his work. In the Daybooks we have Weston’s reaction to Stieglitz, and— filtered through Weston’s eyes—Stieglitz’ reaction to Weston. We also have the comments of the blinkered Salon judges of the twenties—comments which Weston recorded only to dismiss—and the discerning comments of friends which often amused Weston, sometimes angered him, but which always spurred him on to further work.

Weston’s prose is an extremely flexible vehicle which bends easily to reflect his mood and intention. As Weston’s thought, the Daybook is at times lyrical, flippant, matter-of-fact, and joyous. When analytical Weston could be exact and precise; yet, in exasperation and humility he could give up over the loss of a word :

Beethoven cannot move me as does Bach : nor do any of the moderns . . . none have the transcending grandeur, the irresistible force, and surety which sweeps me along with neither intellectual questioning nor emotional excitement. Bach is,—Bach—.

With his increased mastery of the photographic medium, and with his increased photographic and social activity Weston’s need for this prose outlet eventually diminished. The last two entries of the Daybooks were written ten years apart. During this period (1933-1944) Weston was asked to photograph for a special edition of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. It was especially fitting that Weston’s photographs should appear side by side with Whitman’s poems. For what other American artist could better affirm with the joy and wonder of Whitman :

I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars.

JONATHAN GREEN

ALVIN LANGDON COBURN, PHOTOGRAPHER: AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY. Edited by Helmut and Alison Gernsheim. New York, Washington, 1966: Frederick A. Praeger. 144 pp., 67 reproductions. 11 x 9 in. $25.00.

A PORTFOLIO OF SIXTEEN PHOTOGRAPHS BY ALVIN LANGDON COBURN. Introduction by Nancy Newhall. Rochester, 1963: The George Eastman House. 22 pp., 16 reproductions in a loose portfolio, 14 x 11 in. $12.50.

Alvin Langdon Coburn was born in Boston in 1882 and died in Wales on November 23, 1966. By the time he was twentyone, he was active in the Linked Ring in London and the Photo-Secession in New York, the two most advanced and artistically conscious groups of internationally known photographers. Best known are his two books of portraits, Men of Mark (1913) and More Men of Mark (1922). He was among the early experimenters with "abstractions" in photography, notably the scenes of the Grand Canyon (1911) and the "Vortographs" (1917).

Two favorite questions of mine were raised again by the recent autobiography, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Photographer. How does a famous photographer’s interest in his esoteric and spiritual birthright as a man affect his photography ; and, after a long career, what does he photograph during the last period of his life?

Neither the Portfolio nor the Autobiography do more than keep these questions vibrating on the shelf. The Portfolio includes 16 pictures from 1904 to 1917; the Autobiography includes 56 pictures taken between 1904 and 1919 and 8 from between the years 1963 and 1964. The Nancy Newhall text for the Portfolio is compact, fully documented and composed of many quotations of Coburn himself ; the Autobiography adds many personal recollections of Coburn’s work and friendship with the famous men of Edwardian England, notably, George Bernard Shaw and Henry James. Much is reminiscent of Karsh’s writing about his photographing the “great” of more recent decades.

When Coburn became interested in Freemasonry about 1919, his photographic activity was severely curtailed ; but having the power of the medium in his blood, he never stopped photographing completely. Sometimes in the midst of his long years of active work in Freemasonry, he climbed the Welsh mountains in order to photograph clouds on the little lakes.1

He explains the curtailment of his photography in the following :

Friends have sometimes asked me why for many years I ceased to devote my energies exclusively to photography, after having attained a certain proficiency in it through a lifetime of dedication to it.

I think I can justify this change of occupation on the ground of ultimate values. Spiritual concerns are more important, and the art of the inner life is more vital and significant to the supreme and ultimate purpose of the human soul, than any other activity. If you compare photography and religious mysticism as alternatives to which one should devote one’s life, can there be any doubt as to their

i. Autobiography, p. 116. (None of these photographs are included in either book.)

respective importance ?

The greater choice, however, always includes in some measure the lesser. Seek ye first the Kingdom of Heaven and all other things are added unto you, for religious mysticism is the peak of the range from which even the vistas of photography may he beheld in an ever newer, richer and more mysterious radiance.

Photography teaches its devotees how to look intelligently and appreciatively at the world, but religious mysticism introduces the soul to God.2

In the Nancy Newhall introduction to the Portfolio mention is made of a provocative lecture, “Astrological Portraiture,” given by Coburn on November 21, 1922 at the Royal Photographic Society. Although this lecture is omitted from the Autobiography and given but brief space in the Portfolio, the idea of photographing people according to zodiacal types is stimulating. A few years before Coburn died I wrote to ask him about this lecture. I also requested that he write at some length for Aperture about his involvement with photography in relation to the spiritual. There was a cordial exchange of letters, full of evasions although he did promise to get at the problem as soon as his autobiography was completed. Unfortunately, Coburn died November 23, 1966 only two weeks after the Autobiography appeared. In seeking further information I wrote to the Editors, Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, who had worked closely with Coburn. They reported Coburn had said nothing about the “Astrological Portraits.” Yet, in this talk at the Royal Photographic Society, Coburn showed photographs of what he considered to be photographic types based on zodiacal prototypes. For example, he characterized the photographers whose major astrological influence came under the aegis of Capricorn :

The photographer who is born under the sign of Capricorn will be masterful and successful. He will have a large studio on an important thoroughfare, and an extensive staff of assistants. He will make groups of City Company companies and other well-fed and respectable gatherers. 3

I can only speculate as to why he made no reference to this phenomenon in his Autobiography. Perhaps the further pursuit of such a way of seeing people proved too difficult ; or, his continued studies in the esoteric may have yielded the conclusion that the astrological type, which is real enough in various esoteric forms of knowledge, is best kept within the private circles of esoteric groups. So the connection between astrological types and photographing people is still to be explored.

On the subject of photography at the “eve of life” Coburn says this :

The sea at Colwyn Bay, Wales, was frozen for the first time in living memory. I hastened to record it and the simple beauty of its pattern pleased me greatly. Its calm serenity satisfies the soul by its indrawn stillness.

The simplest things are often the most profound, and the people who are able to achieve happiness in simplicity are usually the most serene.

Towards the end of life when its restlessness is stilled and the soul is drawn inward towards its own center, there arises a peace which is satisfying. Photographs of the calmness of nature in her more serene moods may have something of this same indrawn quality. 4

The last eight photographs of the book dating from 4953 to I9^4 do have a serenity that is not found in his work up to 1919. The spiritual attitude which developed in his later work, distinctly separating it from earlier experimentation, can be seen in his intellectual conception of his photography :

In photography, we turn outward to the appreciation and recording of physical things—and how wonderfully exciting they are, photography continually teaches us to appreciate. Yet, behind the everchanging wonder of the material world there abides, immutable and serene, an Eternal Force which is its Cause, and the guarantee of its perfection. We cannot photograph this, but if we can glimpse it with the eyes of the soul, life is changed for us, for the manifested earthly significance.

2. Autobiography, p. 122; Portfolio, p. 18.

3. The Photographic Journal (Feb., 1923), pp. 50-52.

4. Autobiography, p. 132.

The greatest artists have always had a spiritual background, and I venture to suggest that a photographer will not be less proficient in his work if he sees in his subject matter the Master Workmanship of a Divine Creator.5

If my own experience can be relied upon, Coburn’s statements give only the faintest clues and no taste of what the experience is like of leading towards the spiritual. He gives no evidence that he tried to push photography to its outermost limits ; it is only implied that he persistently sought to reveal the inner life.

If there is such a thing as an art of photography some of its practitioners cannot help but involve photography with spirit. On this point Coburn evades the issue. And from the egotistical tone of the text in the Autobiography, the reason why seems clear enough.

MINOR WHITE

5. Autobiography, p. 132.

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Jonathan Green

Minor White

-

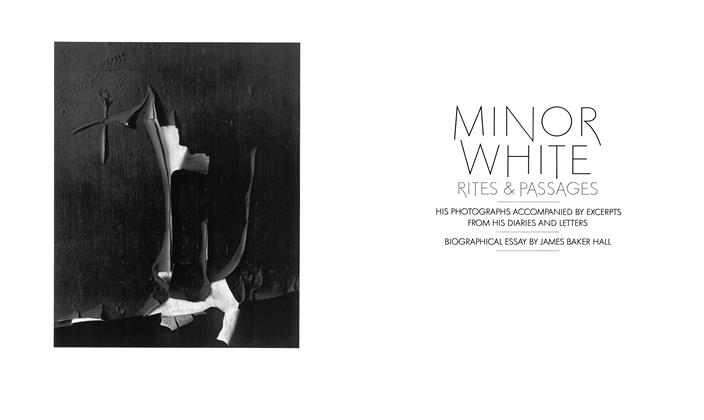

Minor White: Rites & Passages

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall, Michael E. Hoffman -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersA Unique Experience In Teaching Photography

Winter 1956 By Minor White -

Editorial

EditorialDucks & Decoys

Winter 1960 By Minor White -

Editorial

EditorialTe Deum Zeitgeist Drift

Summer 1964 By Minor White -

Could The Critic In Photography Be Passé?

Fall 1967 By Minor White -

Editorial

EditorialAperture's Altered Format

Spring 1959 By Minor White, Shirley Burden

Peter C. Bunnell

-

Leslie Krims

Fall 1967 By Peter C. Bunnell -

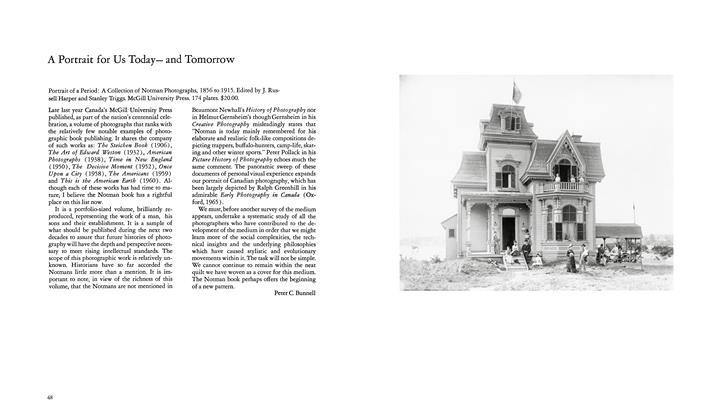

A Portrait For Us Today—And Tomorrow

Spring 1968 By Peter C. Bunnell -

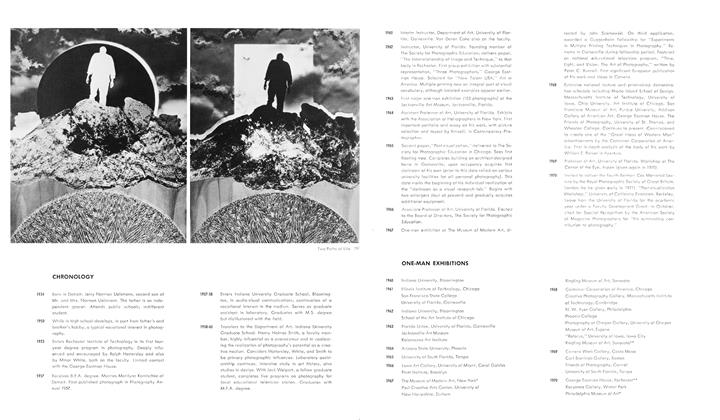

Chronology

Winter 1970 By Peter C. Bunnell -

Group Exhibitions

Winter 1970 By Peter C. Bunnell -

Bibliography

Winter 1970 By Peter C. Bunnell -

Archive

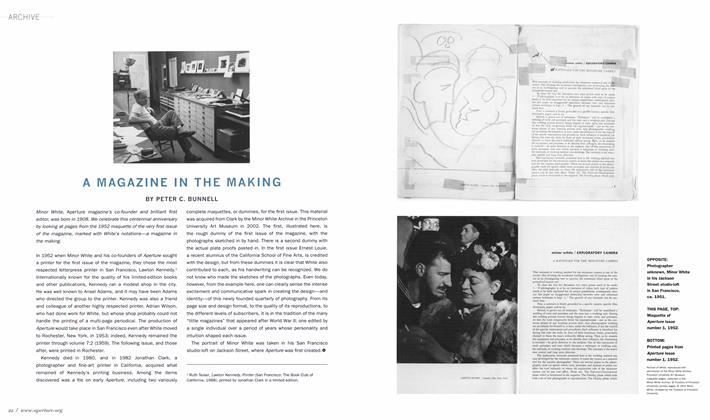

ArchiveA Magazine In The Making

Winter 2008 By Peter C. Bunnell