THE DAYBOOKS OF EDWARD WESTON

BOOK REVIEWS

Edited by Nancy Newhall George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, 1962 214 pp, 40 plates, index, $10.00 to non-members Distributor: George Wittenborn & Co., New York

After three days with the first volume of the Daybooks of Edward Weston, the diary style has taken over my ordinary writing habits. I am tempted to date this—why not?

Rochester, New York 26 March 62

Today a long-held wish has been gratified. I hold a certain book in my hands; I was beginning to think that I never would. At least Volume 1 is printed and that covers the years that Weston spent in Mexico. It is as if the man were back again. The nostalgia sweeps in like the afternoon fogs of San Francisco and any critical sense that I might have had takes a vacation. I find that I do not want to write a book review. Maybe it’s the nostalgia. For a deeper reason I give preference to a reluctance to contribute to any reader’s feeling that he knows a book because he can talk glibly at a cocktail party about something that he has never read.

The nostalgia is personal, what I bring to the reading of the book. (Weston’s writing in a diary has its share of memories mixed with positive and generative statements.) For one thing I relive the days and evenings in Weston’s house perched over the Pacific Ocean. Especially the time when he let me read what he had written in his Daybooks. As fast as I would finish one notebook he would find the next: Mexico, California, Mexico again ( where the first volume stops ), the long Carmel and Lobos years, the Guggenheim fellowship. The light poured in the window, the skylight, and I over the mutilated typescript. Edward had edited with a razor blade. Seeing in the words the man unfold during his fruitful years long before I met him was a strangely moving experience. Much came together, his whole influence on me when I was learning to photograph and live. Another kind of affirmation, this time written—to add to the support he had given me by gesture and glance as I tried to work at Point Lobos.

But a bit about this unfolding of his that moved me so. Schooling past, he went to Mexico—not the three R’s but camera. He did not learn photography in classrooms, but mainly in professional photography the same as thousands of others. Self taught really. By 1920 he had earned his spurs. In Mexico he tried them out. At first recognized as an artist by the powerful artists and cultured class of Mexico City—in fact this was his first recognition as an artist—he luxuriated in recognition like any young lion—still we can see laid in those few years the beginnings of the man as an artist of a different order. These glimmerings of an independent artist, or artist in another and deeper sense were written down with all the rest. Bullfights, passing love affairs, the city, public pubs with romantic names, market places, food, drink and the constant making of portraits to earn his living is all a part of making pictures. The way he lived photography, any separation between man and artist, on whatever level, seems slight. Looking back at least through the pages of a book—some drive, some compulsion, inner stamina, why not call it soul, began to make itself felt and Weston heeded the promptings. A dozen years later I can trace a little of why I was so strongly affected by his Mexican Daybooks. Because another had surmounted the turmoil of his own beginnings, I felt affirmation for my own shaky foundations.

Reading the notebooks in his house, in the sunlight, in his presence—that was similar to watching a slow motion movie of some life process that would lend itself to such drastic treatment. Yet he had borrowed himself for his own relentless observations and wrote facts and conclusions down in the hour before dawn.

27 March, 5 AM

To reconsider this man who influenced me as far as I was able to be affected, or permitted myself to be—that is to either go under in a soft foam of memorable euphoria, or march unerringly through a relentless desert. As I continue reading, the vivid images of his presence flicker across the pages. Either and or—somewhere he learned that yes and no are as the two feet of a man. In my memory his presence stands clearly balanced between sensuous love of living and disciplined self scrutiny. Not one or the other; the harmony instead, or resonance, that says "no” only to those things that stand in the way of inner development. He is still a moving force.

Steaming coffee—dawn through a horizon slit in the clouds—it will be a cloudy day in Rochester. Will we have to wait another ten years before Eastman House or some other publisher produces the second volume for us? At Lobos and on his trips across the country, the inner growth first appearing in Mexico takes form in words and photographs. His growth inwardly never stopped even though the Daybooks, after fifteen years, were discontinued when a way of working was forged. And further growth left words behind. In later years he said little, "How young I was. That covers everything.” He showed us photographs that covered the wordless.

Minor White

Simpson Kalisher/RAILROAD MEN

Introduction by Jonathan Williams Clarke & Way, New York 1961 84 pp. $6.95

RAILROAD MEN is a competently designed, neatly executed compilation of railroad lore and photographs. The book and fifteen portfolios of original prints represent the efforts of a photojournalist to come to grips with his medium on his own terms, without the pressures of deadline or editors. The idea for the book came while on a magazine assignment. Later, on his own time, Kalisher photographed and taped interviews with railroad men in an attempt to bring to life the romance and lore of this peculiarly American industry.

The text consists of selected stories and anecdotes from the tapes. In a few instances, the text and photos evoke in unity, but for the most part they are unrelated. The text is often rough good humor, charmingly Bunyanesque, but the faces of the men in the photographs reflect the effects of hard physical labor and the monotony of lifetimes spent in nursing heavy machinery. The photographs, all skillful and competent, are the product of the bread and butter photojournalist, and often lack the poetic edge that turns fact into truth. The viewer never feels that the author has really come to "grips” with his medium as he states as his purpose in the epilogue.

The introduction by Jonathan Williams compares RAILROAD MEN to Wright Morris’s THE INHABITANTS, but the dynamic balance of words and pictures in THE INHABITANTS is rarely achieved by Mr. Kalisher. The book illustrates both the pitfalls and advantages of what can happen when a photojournalist gets his wish and works without the guiding hand of the picture editor.

Mr. Kalisher’s seeing is deliberate, accurate, and sophisticated, but only in a few instances does he evoke the immediacy of discovery or the moment of insight that makes the common the very uncommon. The epilogue, the author’s candid and honest appraisal of his project, demonstrates a detached and knowledgeable critical ability, and reflects a vast potential of growth.

John Upton

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

John Upton

Minor White

-

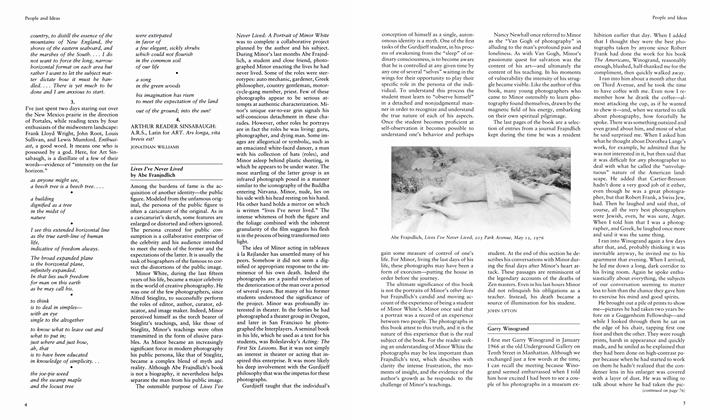

Minor White: Rites & Passages

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall, Michael E. Hoffman -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsAndreas Feininger / Advanced Photography

Fall 1952 By Minor White -

The Zone System Of Planned Photography

Spring 1955 By Minor White -

Editorial

EditorialEditorial

Fall 1958 By Minor White -

The Bitter Years

Fall 1962 By Minor White -

A Balance For Violence

Spring 1968 By Minor White

Book Reviews

-

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsThe Focal Encyclopedia Of Photography

Spring 1957 -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsThe Stereo Realist Manual

Spring 1955 By Beaumont Newhall -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsBook Reviews

Spring 1954 By Byron Dobell, Minor White -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsA Dialogue With Solitude

Fall 1965 By Linda Knox -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsHenri Cartier-Bresson / The Europeans

Spring 1956 By M.W. -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsHenri Cartier-Bresson / The Decisive Moment

Spring 1953 By Minor White