The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Department Of Photography At The Rochester Institute Of Technology

1. THE DEPARTMENT IN GENERAL

Spring 1957 C. B. Neblette, Hollis N. Todd, Ralph M. HattersleyThe Department Of Photography At The Rochester Institute Of Technology C. B. NEBLETTE, HOLLIS N. TODD, RALPH M. HATTERSLEY Spring 1957

THE DEPARTMENT OF PHOTOGRAPHY AT THE ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

1. THE DEPARTMENT IN GENERAL

C. B. NEBLETTE

Chairman Division of Photography

and Printing at the Rochester Institute of Technology

It is not surprising that Rochester, the home of Eastman Kodak, Graflex, Haloid, and other well-known names in photography, should have a school of photography. Nor is it surprising that it should be concerned with the science of photography and the manufacture of photographic materials. But Rochester is also a city with artistic interests, and the Department of Photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology reflects the creative aspects of photography no less than the technical and scientific.

The Institute itself was founded back in 1829 and has ten other departments including departments of Art and Design, Graphic Arts Research, Printing and the School of American Craftsmen. It has resources of approximately fifteen million, a full time enrollment of 1800 and a part-time enrollment of 4,500 (1956-57). The Bachelor of Science and the Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree are offered in all ten departments and in twenty-five different programs.

The Department of Photography offers the Bachelor of Science degree in two programs: Photographic Science and Applied and Professional Photography; and the Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in Illustrative Photography. It has a faculty of thirteen full-time members and twenty-six part-time who are recruited from other departments, such as Chemistry, Art and Design and General Education, and from industry and museums in the city. Its facilities occupy one floor of a modern building with approximately 30,000 square feet of floor space, designed especially to meet the needs of a photography department. There is an investment of well over Si 50,000 in cameras and other photographic equipment.

Buildings and equipment, important as they are, do not make a school. Only a clear concept of what one is trying to do, constant study of how best to achieve these ends, an able, hard working and enthusiastic faculty, can make a vital program. All these R.I.T. has in full measure. Its objective is simple: To provide the best preparation for a career in photography that it can organize and present to the best equipped students it can find. This major objective involves many things. It means for one thing selecting as students young men and women who will be able to profit from instruction. It means the development of courses and curricula for different areas in photography for, obviously, the studies required for a career in photographic technology are quite different from those required for advertising photography or photo-journalism. It means providing courses and experiences for the growth of the individual as a personality. Consistent

with the school’s aim this is done by broadening the student’s perspective on science while at the same time increasing his sensitivity to life and the world about him, and his ability to express himself through photography. Thus, courses in the basic sciences and the spirit and methods of science form a part of the disciplines in photographic technology; while the student in picture making photography, in addition, concerns himself with art trends, creative sources and the problems of communication as applied to his chosen area in illustration. For all of these, however, there is a common background in the materials and processes of photography, its practice and the development of good craftsmanship and technical ability. The Department takes the position that the photo-journalist, the advertising photographer, in short the creative user of the photographic process, should know that process and its graphics thoroughly; not simply the techniques for obtaining the desired results, but the basic theories of the various processes as well. The emphasis on the photographic process as such, is often questioned by students whose interests are primarily creative, and occasionally by other photographers. It remains, however, an integral part of the R.I.T. approach; a dualism perhaps not unlike the Greek ideal of a trained intellect in a beautifully proportioned body.

It is not enough that men be able to do what they are told ; to copy what they are shown. They must develop resources which will enable them to face and solve new problems in new ways, and thus constant experimentation in the solving of problems in design, in science, in technology, in craftsmanship, in the interpretation of photographs which we call ''communication” is fundamental in the R.I.T. approach to education for photography. In short this means as much, or more, attention to the fundamentals as to the means and ends. It means providing a basis for original thinking whether in the science or the picture making aspects of photography. It also means the solving of practical problems; problems that are typical, that meet existing needs and requirements.

"Man does not live by bread alone,” but it is equally true that without bread he does not live. Sound, thorough, comprehensive training in photography is essential, but alone it is not enough. These are but the tools of a career. The young man or woman must be able to use them intelligently, to constructive worthwhile ends. Our aim is to do what we can in four years to help young men and women to develop themselves in both directions.

2. THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SECTION

HOLLIS N. TODD

Instructor

Rochester Institute of Technology

Documentary, scientific, and creative-expressive photography are all possible only because of the army of technically trained people—scientists and engineers—who develop the methods, materials and equipment used by photographers. Photographers themselves, confronted with an increasingly complex array of films, cameras, developers, lamps and so on, find that reliance on trialand-error methods is now no longer dependable in any kind of photography. To make consistently fine photographs requires a high degree of familiarity with, and understanding of, many techniques and many kinds of technical information.

This is the basis for requiring that every student in the Department of Photography at the Rochester Institute of Technology acquire a foundation in mathematics, chemistry, and physics in his first year. Courses in these subjects supplement the study of the elementary theory and practice of photography: (1) mathematics, for example, provides a background for working with the formulas and graphs widely used in the presentation of technical photographic data; (2) general chemistry is necessary for understanding the essentials of the exposure and processing of photographic materials; (3) the physics of light leads to the consideration of the nature of light sources used in photography and to the theory of color photography. Sensitometry, the methods of measuring the response of a photographic light-sensitive material, draws upon all the fundamental sciences to clarify the nature of the entire photographic process.

The program of the second year varies, according to the area of specialization selected by the student. The student who selects illustrative photography as a major broadens his technical foundation for creative work by further study of (1) chemistry, with specific application to the details of the photographic process, and (2) optics, which involves the study of lens performance and evaluation, and the design of optical equipment such as rangefinders, viewfinders, and projectors.

The science student in his second year pays especial attention to the technical aspects of the control of photographic processing. Besides the course in photographic chemistry previously mentioned, emphasis is given to two kinds of study which involve chemical and photographic methods of insuring quality in the processing of films and papers: (1 ) technical analysis, which is the application of quantitative analysis to developers, stopbaths, and fixers; (2) advanced sensitometry, which broadens and deepens the student’s understanding of problems in the measurement of photographic emulsions, and which extends his knowledge into the complex field of color photography.

The experimental method is continually employed in the laboratory portions of these courses, and the student is encouraged, as his experience grows, to strike out on his own in formulating and carrying out moderately complex problems. By this method he gradually moves toward the field of research: he reads widely in the literature available in the library; he applies this information to the problem at hand; he exercises his ingenuity in dealing with unfamiliar materials and techniques.

Paralleling the student’s exploration of the scientific background of photography is an extension of his ability to manipulate photographic equipment and materials; he gains much additional practice in solving practical photographic problems, with special attention to color materials. He learns good studio and darkroom practices, he gains experience in processing, and through a variety of experiences, he sees how theoretical understanding contributes to a more refined and precise control of photographic operations. The newest materials and processes, as well as the long established, are subject to his experimentation.

If a student wishes to continue in technology, the Department offers a further two-year program of study leading to the degree of Bachelor of Science. The emphasis in the third year is placed upon fundamental mathematics and science; general physics, calculus, and physical chemistry strengthen the student’s scientific foundation for more advanced specialization. A study of statistical methods for quality control leads to a comprehension of the methods required for strict evaluation of the techniques used in the commercial processing of photographic materials, especially color materials where conditions arc much more critical.

By the fourth year the student in the photographic science program is ready for advanced courses in the theory of photography, the applications of photography to scientific research, and special problems in the manufacture and handling of photographic emulsions.

An unusual part of the last year of this program is the opportunity given the student to attempt a comparatively ambitious research problem, selected by the student on the basis of his interests and abilities. He takes full responsibility for the preparation and execution of extended experimental work, lasting for a period of several months. As evidence of his accomplishment he prepares a fullscale written report, as well as periodic oral accounts of his progress as the work proceeds.

Associated with his research activity is a seminar in the history, methods, and philosophy of science. Class discussion draws on a wide variety of readings in many references, historic and contemporary; in addition, the total past experience of the student is brought out and examined. This kind of exploration helps the student to see the role of science in human affairs of the past and present, and helps him to relate himself and his activities to the scientific and technical world he is about to enter.

A significant feature of much of the laboratory work throughout the student’s experience at R.I.T. (but especially in the latter part of his last two years) is the group activity involved. Students typically work in teams having a few members jointly planning (in part at least) and carrying out their assigned problems. This learning method has several desirable effects: students learn from each other as well as from their instructors and their reading; students learn to appreciate the need for effective cooperation to attain a desired result; and studies in general education, particularly psychology, take on a new significance when they are actually put into practice.

3. THE ILLUSTRATIVE DIVISION

RALPH M. HATTERSLEY

Instructor

Rochester Institute of Technology

All students in the Department of Photography are taught some of the fundamental concepts of creative-expressive photography in their first and second years. Those in the Photographic Technology program take such work for its enrichening effect, and to impress on them that picture making and picture interpretation is a form of literacy. Students in Applied and Professional Photography go beyond lectures and concepts and put the ideas of communication and evocation into practice because, for many of their purposes, anything less is not good enough. For those studying Illustrative Photography, creativity in its many aspects is all important.

Creativeness is not so much taught as approached. To this end the student is encouraged to explore his world — the visual world — with fresh eyes, seeing familiar things with new insights, discovering the world of light, form, shape, texture, and color, finding myriad kinds of relationships and meanings, tangible and intangible, lasting and ephemeral amongst visible things. He is encouraged to explore the psychology of human action and reaction using himself as a guinea pig, as did I'reud, if necessary. In so doing he unleashes in himself longfettered sensitivities and powerful creative urges. He explores his own mind to understand the minds of others. He studies the creative process as it works in painters, composers, architects, novelists, poets, and dramatists. He explores carefully the photographic process to learn its controls and in order to produce a wide diversity of images. He studies these images, realistic and non-realistic, sensible and non-sensible, dynamic and static, beautiful and ugly, to discover what they signify or suggest, to learn how they may be utilized in advertising and in art. He attempts to discover all the possible kinds of visible things, kinds of textures, shapes, lines, colors and combinations of these as colors and shapes, shapes and textures, etc. He endeavors to develop sensitivity to every possible kind of stimulus, and, in so far as he is successful, becomes a kind of harp which vibrates to the manifold stirrings of things in the sensible world about him.

The student in the Illustrative Division is expected to go beyond discovering what is already available in the world for him to see and feel, he is urged to invent. For instance fresh, sparkling color combinations, dramatic new lightings for familiar subjects, exciting arrangements, new kinds of backgrounds for portrait studies, strange croppings, unique tonal relationships, unheard of linear and textural effects, and so on. Fortunately, the photographer who has freed his natural creativeness invents easily, almost compulsively, as if he were feeding on his own inventiveness.

It is not enough, however, to explore and invent. To be a "creative” photographer we feel that he must communicate his discoveries and inventions to audiences. He must know people, all kinds of people. He learns the meanings they attach to things and events. He is a student of the visual language, its origin,

its growth, its current usage. He must know himself and his own peculiarities and his many audiences and their peculiarities, so that he may construct visual communications (photographs) which will be interpreted by viewers in the sense that he intends them.

Students come to us with many popular misconceptions regarding the nature of creativity. For example, creativity is often confused with anarchy, superficial artiness, blind experimentation, oddness for its own sake, childish rebellion against cultural tradition, even a form of insanity. Many believe that the creative photograph is the one they don’t like and don’t understand, or is moribund and disorganized, or is the one made by following the "creative recipes” set forth by the camera magazines, i.e., it’s a solarized, bas-relief, high contrast, or hyposplashed print. Instructors at the Institute steer their students around these erroneous notions.

Creativity is treated as a normal development of the healthy personality. It has substance and durability. It is practical and sane. It is an attribute of human mentality in its highest development. At the Institute we believe that a photographer should be many-faceted; a scientist, a craftsman-artist, a citizen. Our curriculum in Photographic Illustration is constructed around this concept.

During the first two years the student is subjected to a rigorous discipline during which, as was stated earlier, he begins to understand the theory and practice of photography; furthermore to read and evaluate both printed matter and pictures; and finally to express himself adequately both verbally and pictorially. Color photography is emphasized in the second year for all students; electives are also offered in photojournalism, portraiture, or commercial photography. In the liberal arts area such courses as Psychology, Public Speaking, Economics, English Communication, and Visual Communication are programmed.

The student who elects the Photographic Illustration for the third and fourth years leaves behind all technological courses at the end of the second year. Art, Literature, Philosophy, History, Creative Writing are offered. In photography his work is design-oriented, expressive, and experimental. The student is always aimed at a high level of craftsmanship and artistry. He works with subjects ranging from non-objective design to expressive interpretations of people or abstract ideas. The aim is a well grounded photographer who can apply his talent and his craftsmanship to the problems of future clients.

The rigorous external discipline of the first two years is largely replaced by an internal, self discipline. The student is given great freedom of choice of subject matter and treatment of photographs. Self expression is strongly emphasized. During his fourth year he undertakes projects of considerable difficulty. Plans, photographs, prepares layouts, writes text and captions, executes under supervision and finally presents a finished project of professional caliber.

After four years he is expected to be an independent, articulate, sensitive, photographic illustrator. He is prepared to go into a professional field, or to go into a graduate program as the case demands.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

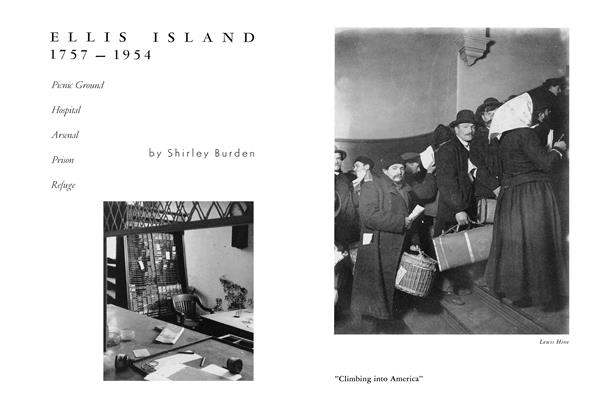

Ellis Island 1757-1954

Spring 1957 By Shirley Burden -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersThe First Indiana University Photography Workshop

Spring 1957 By Henry Holmes Smith -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersTeaching The History Of Photography

Spring 1957 By Beaumont Newhall -

Photography

PhotographyPeeled Paint, Cameras And Happenstance

Spring 1957 By Minor White -

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal CommunicationMore Books For The Creative Photographer

Spring 1957 By Robert Forth, Walter Snyder -

Notes And Comments

Notes And CommentsNotes & Comments

Spring 1957

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

-

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersA Symposium / Part 3

Spring 1957 -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersLearning Photography At The Institute Of Design

Winter 1956 By Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersTeaching The History Of Photography

Spring 1957 By Beaumont Newhall -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersPhotography At Ohio University

Fall 1956 By Clarence White -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersA Unique Experience In Teaching Photography

Winter 1956 By Minor White -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersThe Photo Short Courses

Fall 1956 By Vincent Jones

More From This Issue

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

-

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersA Symposium / Part 3

Spring 1957 -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersLearning Photography At The Institute Of Design

Winter 1956 By Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersTeaching The History Of Photography

Spring 1957 By Beaumont Newhall