The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

A Unique Experience In Teaching Photography

THE CAPSULE COURSE

Winter 1956 Minor WhiteA UNIQUE EXPERIENCE IN TEACHING PHOTOGRAPHY

MINOR WHITE

Photography Instructor, Rochester Institute of Technology

When seventy-five year old California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco introduced a photography department in 1946, the way was opened for a race teaching experience. This unusual program, which lasted seven years, may be quickly summed up as an experience of teaching photography at graduate level —and as an experience in teaching photography the only way it can be taught effectively, namely by doing, by intensely doing.

Since that time the school has become accredited and the present course now fits undergraduate academic standards. This new regime may also be summed up: in the words of one of the present instructors, "the students no longer have time to make photographs!’’

Consequently when I set down some of the most important concepts that we used in teaching camera work I will have to rely on my memory of that fabulous experiment.

Many factors contributed to the uniqueness of that experience. One of them, not necessarily the most important, was the quality of the students themselves. They were GIs from the second world war full of plans after the long futility of no planning; older, most of them experienced in photography, in school because they chose to be. Furthermore there were so many applicants for the 36 places that we screened with lengthy interviews. Their enthusiasm was truly remarkable: an instructor could only ride high on the wave of teeming personalities. Another factor was the location of the school: San Francisco itself is a stimulating experience, cosmopolitan, dramatic, western, and full of verve. Its white buildings sweep across the hills like surf on a reef of rocks. The blue ocean at the city’s tip does the same. Then, too, San Francisco is a center of intensive photography. Consider its magnets of photography: Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange, Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham. These were the names to conjure with at that time and all of them were so interested in the school that they gladly taught or lectured in their respective fields.

Speaking of guest instructors, Lisette Model taught the second year class in minature camera for six weeks one year; Homer Page taught minature camera work for an entire year.

Still another factor was the nature of the school policy. The department had been set going by Ansel Adams at the request of the school’s war time President, Eldridge T. Spencer, as part of a plan to up-date an old, comfortably academic private art school. The school went uncomfortably modern practically overnight under the directorship of Douglas MacAgy ; the changeover, however, generated a high creative excitement in both students and staff. In this atmosphere of abstract painting, non-objective drawing and experimental sculpture the photography students got a bird’s eye view of their own medium such as is rarely accorded students of photography. And because it was done by students as enthusiastic as themselves, they did not cast the abstract approach lightly aside. They came saying, like good GI’s "this is for the birds” and stayed to see that when this was superior it had spirit. Once they could see the spirit in modern art, they could usually find it in photography.

The teaching policy of the school contributed greatly. Students were taught by doing. The program was as flexible as possible; each class was three hours duration, and four of the five days a week was spent in photography. This fitted the teaching of photography exactly because lectures, shooting schedules, dark room time, critiques, both individual and class could be scheduled to fit each project. Projects might be as short as a week or as long as a term, nevertheless we could schedule by the project. This flexibility, this fluidity of programming was perhaps the one single factor that contributed the most to the uniqueness of the experience — for both student and instructor. The students could, and did, live the life of the practicing photographer for days on end: the instructors could maintain the kind of apprentice-tutorial-conservatory method that they felt to be particularly pertinent to teaching photography.

Another factor was the personalities and contributions of the instructors. As was said the department was inaugurated by Ansel Adams. Tutor-taught, musician-trained, he brought the conservatory methods of teaching to the department. This method of teaching, stated briefly, encourages the student to work by himself until he reaches his own ceiling and then, and not until then does he go to the instructor to have that ceiling raised. Adams also brought to the department his famous discipline of technique what was codified under the name of "the zone system of planned photography.” The zone system is a means of linking the science of sensitometry to the art of picture content. This last means that the photographer has a logical and controllable way of interpreting the scene in front of his camera in terms of photography. Simple as this may seem, as the students soon found out, a mastery of the zone system meant the difference between being camera-handled or man-handling the camera. The third Adams contribution was the idea that only the free lance photographer could be a professional in the sense that an architect or a doctor is a professional.

I, on the contrary, was trained in colleges with majors in science and the history of art and photography. Consequently I brought to the department academic teaching methods; thus lectures supplemented the long tutorial individual conference sessions. To parallel the zone system which gave a method of interpreting the scene in terms of the photograph, I introduced an analytical method which allowed interpretation of the photograph itself in terms of the human consumer. This method was called, for teaching purposes, "space analysis.” It was found to be useful to future photographers, picture editors and potential critics alike.

When Mr. Adams left the department to become its advisor late in the first year, the technical side was taken over by William Quandt, Jr. who covered everything from the zone system to photograms. I continued, as the non-technical member of the two-instructor team, to approach the creative side of photography both directly and indirectly. For the direct approach to creativity we borrowed a title from Alfred Stieglitz, namely "equivalent.” With that term we deliberately photographed for what photographs can suggest. We consciously and determinedly went after what photographs could suggest above and beyond the subject of the pictures. Much to the surprise of the more conventional students it was found that what photographs obviously convey is often meager compared to what they can convey by suggestion. For the indirect approach to creativity (which is the more successful when coupled with a direct approach) we depended faithfully on osmosis.

To link "creative” photography (and we emphasized the creativeness that happens at the moment of seeing over the kind that takes place in the dark room) to professional work and the professional attitude we made a distinction between the words "expressive” and "creative.” As artificial as this distinction was it served the purpose of indicating to the professional his responsibilities as a creative photographer. The "expressive” was personal: it stood for the use of the camera to discover the photographer's own inner condition, his own inner self, and during a three year period the student could trace his own inner growth to some extent, by "expressive” photography. This knowledge and distinction we considered essential to photographers who might be expected to work as artists, because through such self discovery, they learned what they had to say. The second term "creative” stood for making photographs so that what one had to say was communicated to another person. And communicate to him by the photograph. The photographer was expected to know what he had to say so well, that he could find the right means, the proper photograph so that another person would understand what he was trying to say. The "creative” photograph was expected to evoke a mood or "create” one in the spectator. Furthermore, this mood to be evoked was to be predetermined by the photographer.

To the would-be "artist” photographer, "expressive” and "creative” were equally important; with one he learned for himself what he had to say; with the other he found the means to say it. Exclusive production of the "expressive” was compared to unplayed music. The professional artist-photographer on the other hand was compared to the concert musician who both composed and played his own work.

The long list of factors that contributed to the uniqueness of the department may be terminated with a paradox and a slogan. The paradox: the student was encouraged to see privately and at the same time driven to enact the ideal of professionalism. He was encouraged to see with eyes of a poet; and held to being able to apply his training appropriately to the needs of a client. It was constantly held up as an ideal that a trained photographer could apply both his talent and his training appropriately.

The slogan: "I don’t want excuses, I want photographs!”

THE CAPSULE COURSE

In our attempt to fit the aesthetically talented student to a society that holds commerce more dear than spirit we came to several conclusions. The most important of these still seems to be the "capsule course” that was introduced during the third year of the department’s existence. The students for this course enrolled for one year only. They had to be college graduates with majors in the humanities — or upon sufficient persuasion, seasoned professional photographers. The capsule course was conducted in an unorthodox manner. Upon entering, a tailor-made outline of study was determined after lengthy interviews for each student. In general these students took the classic view-camera technique, the discipline of "space analysis" and the approaches to "creative selection" with the first year men. Miniature camera technique and its rationale of creativeness (called "recognition”) was practiced with the second year men. With this second year group they also practiced the photography of people as individuals. This last amounted to both portraiture for commerce where the pleasing likeness is the sole demand and portraiture for character revelation, an area in which the camera is an unsurpassed tool of penetration. With the third year men they explored the philosophy of photography, communication and criticism. The third year seminar was properly their class. In it photographs from a very wide variety of sources were discussed both formally and informally, both by rule and intuitively. This class met for one three hour session per week throughout the entire year. The college graduates invariably brought to this class unparalleled maturity and solidity. The result was enthusiastic sessions that occasionally built up to an unforgettable group experiencing of photographs.

The three-hour sessions were especially intense when the photographs of a seminar class member were up for discussion. The member was sure of a disturbing experience; his style was defined, his sins of omission as well as those of commission were listed, his power to communicate was evaluated in terms of "expressive and creative.” The man behind the photographs was sought through an analysis of his choice of subject and treatment thereof—and always found. The inner man could not hide behind the mask of the photograph with class members as it could with strangers. Such an experience might have been nothing short of traumatic, but by some grand good will the afternoon was always creative rather than destructive. Criticism was always sympathetic rather than antagonistic. Consequently the individual under fire saw his own work in a new light and his horizons were widened once again. This time, not by an instructor, but by his own friends. By this method the value of the ideal critic was made apparent. (This critic that has yet to make his appearance in photography; the one whose taste and integrity and background will always be equal to the most uncompromising photographer.)

The tailor-made aspect of the program really took place in the private conferences. These tutorial periods were of untold value to the efficiency of the capsule course. The individual’s problems were subjected to frequent discussion ; his individual progress related to the photography itself over and over again. And many a time a three-hour session would extend indefinitely over drinks and dinner.

The year of the capsule course was one of total immersion for the student. It was much the same for all the students, but the one-year man had a time limit that led him to steep himself more thoroughly than the three year men did. The concentration paid off for these one-year men; esthetics blossomed with technique, picture making developed quickly into picture editing, communication grew almost directly out of personal expression, criticism, based on a generous knowledge of photography, developed into a kind of passionate objectivism, and the ideal of professionalism that only the free lance photographer can achieve became a reality—to be able to put at the service of a client a craftsmanlike technique, a craftsmanship of feeling and a craft of communication.

To the surprise of the instructors this course proved basic, not only to photographers, as we had planned, but to potential picture editors, future critics, instructors and a dozen other occupations in the world that depend on picturemindedness.

EDWARD WESTON AND POINT LOBOS

The climax of every year was the five day, early spring trip to visit Edward Weston and to photograph at Point Lobos State Park which his pictures have made famous. Full-time concern with photography was nothing new with us, but on this trip the intensity rose like a thermometer held over a match flame.

Until he became too ill, Weston showed us the beauties of the park itself. He made the students leave their cameras in the cars the first afternoon knowing full well that otherwise they would have all gone to work in the first hundred yards. He annotated one magnificent spot after another, always stopping at the ancient Cypress stump he photographed first in 1929. Under his guidance the years ticked by a picture at a time. It slowly dawned on us that this rich place was a little like a lumber yard to him, stocked with the material for a million pictures. From the depth of his honesty he said that he but scratched the surface and encouraged everyone to do more.

This first contact with the man and the place was rounded off that same evening. After dinner in nearby Carmel or Monterey the group drove to Weston's cottage to see the man and his photographs. The single flood lamp was rounded up, a brighter bulb put in and Weston took out a stack of prints from their cases. He selected carefully, put them, one at a time, on the spotlighted easel. He talked quietly or not at all, answered questions, purred to his cats and kittens vying for the attention of the audience. He never belittled his work, never boasted, but let each picture speak for itself. He obviously handled each print with affection. Here was a man who, all his life, had pursued photography as an art. And we looked. With the sound of the sea pounding in our ears, the smell of a log fire around, many of the seeds, planted during the year, sprouted. All that had been said about integrity, love of medium, self respect combined with humility, the growth of the inner man made manifest by his photographs was suddenly visible. All came to focus in the person of this mature photographer. Man, place and photographs merged into a totality in front of our eyes!

Lobos is a strange place and students reacted violently—for or against. Somehow its outward manifestations of worn beaches, plunging cliffs, twisted Cypresses, a Pacific blue as mid-ocean, succulents that gleamed like frosted stars in the forests, often fall into patterns suggestive of a man’s inner self. His hopes, fears, hungers, inner drives and hidden corners seemed to be nearer the surface here than anywhere else. The slightest observation revealed it. Consequently, individuality was stamped on all the photographs made on these trips. Personal expression always ran high. Some students returned with pictures of great beauty, others with nothing, they found the place incompatible. These were usually the ones who had a passionate drive towards people and a weak one towards nature. Since we treated the photographs made at Lobos, not as an assignment, but as indicators of personality, whatever was turned into class was evidence. The trip’s photographs brought home to most students that the camera really was a means of personal expression. If they doubted that before, they were convinced afterwards. Often how much of them was uncovered with the camera came as a distinct shock. The psychological aspect of camera work was thus touched upon. We explored this capacity of photography only long enough to convince the interested students that it would take an expert psychologist or psychiatrist to unravel the entire skein revealed by the photographs. We retreated from this exploration, perhaps a little reluctantly, knowing that we had crossed the borders of picture esthetics and picture interpretation into the realm of the therapeutic. But then we always went too far in any direction ; technique, esthetics, interpretation ; in order to find out what far enough was.

CONCLUSION

If any single factor can be said to stand out to make this seven-year experiment unique in teaching photography, it was the freedom to concentrate on photography. With that concentration we could take a person who thought himself enamored of photography and give him so much camera work that he discovered for himself that in order to be a photographer he had to know everything else in the world that he could possibly learn. We could teach photography as a way to make a living, and best of all, somehow to get students to experience for themselves photography as a way of life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

The Errand Of The Eye

Winter 1956 By Rose Mandel -

Of People And For People

Winter 1956 By Myron Martin -

Letters To The Editor

Letters To The EditorLetters To The Editor

Winter 1956 -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersCan Photography As An Art Be Taught?

Winter 1956 By William Rohrbach -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersLearning Photography At The Institute Of Design

Winter 1956 By Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan -

Editorial

EditorialA Motivation For American Photographers

Winter 1956

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Minor White

-

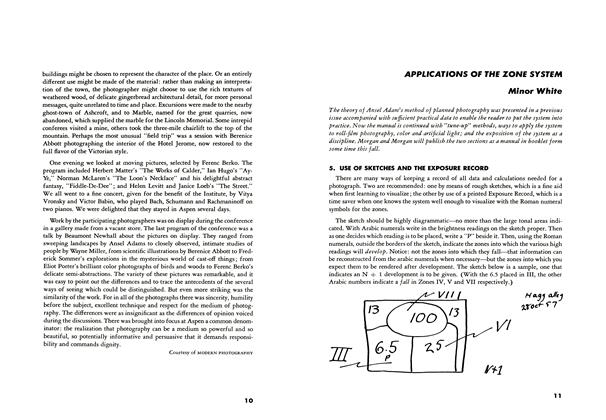

Applications Of The Zone System

Fall 1955 By Minor White -

Photography

PhotographyPeeled Paint, Cameras And Happenstance

Spring 1957 By Minor White -

Editorial

Summer 1961 By Minor White -

Could The Critic In Photography Be Passé?

Fall 1967 By Minor White -

Notes To A Visual Editorial

Fall 1992 By Minor White -

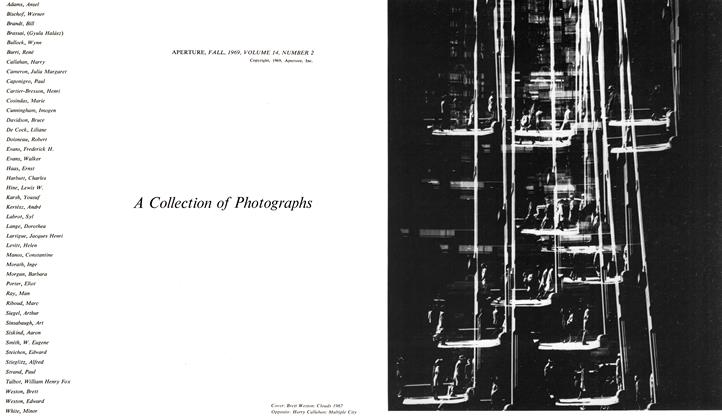

A New Collection Of The Art Of Photography

Fall 1969 By Minor White, Nancy Newhall, Beaumont Newhall

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

-

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersA Symposium / Part 2

Winter 1956 -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersA Symposium / Part 3

Spring 1957 -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersLearning Photography At The Institute Of Design

Winter 1956 By Aaron Siskind, Harry Callahan -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersPhotography At Ohio University

Fall 1956 By Clarence White -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersPhotography At The University Of Minnesota

Fall 1956 By Jerome Liebling -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersThe Photo Short Courses

Fall 1956 By Vincent Jones