Andreas Feininger / THE CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHER

Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, 1955. $4-95, 329 l>p., 63 illustrations.

THE CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHER is one man's attempt to analyze a subject, to comprehensively cover a subject that would be a challenge to the most astute of aestheticians; so it was with great hopes that I took up the book.

Over the past fifteen years Mr. Feininger has dealt with this subject off and on, starting with his excellent NEW PATHS IN PHOTOGRAPHY. He has evolved a style of comprehensive academic presentation, though he occasionally decries this dreadful person. The style has been used to best advantage in his technical works on black and white and color. Now in this book, this apex, as he says, and final effort in his photo-literary career he energetically spaded up his previous ground work, planted outlines, summaries, rules and definitions with a liberal hand. The reader is the one that gathers the crop of wooden concepts choked in a briar patch of organizational confusion. Who says that editors are not a blessing to readers and a preserver of author's reputations?

Feininger’s prowess as a technician can not be denied ; his comprehension of and experience with the widest angled lenses and the longest focal lengthed lenses is probably unsurpassed ; neither can one deny his sincerity, nor overlook the many truths that he sets down in passing—they abound. What then is wrong? Why do the expectations aroused by the title of the book fall to the ground?

First, however, we need to know what stand he takes in this summary of his aesthetics. What does he consider to be creative in photography? There are two parts to it; first, certain graphics inhere in the medium and therefore all of them should be at the command of the photographer. (' Graphics” include all the kinds of lenses, films, papers and physical-chemical-optical manipulations of same.) Second, that with the graphics at his command the photographer can give "new form to" any object that he photographs.

This theory of creativeness is similar to if not the same as that defined by Dr. Otto Steinert in SUBJEKTIVE FOTOGRAFIE 2 as Absolute Photographic Creation. And it is subject to the same criticism ; namely that when a theory of creativeness is taken from the other visual arts and applied to photography in a literal way it leads past or beyond unique photography; the only logical conclusion is a dematerialized object lying on an operating table etherized by a sewing machine. If painters with brushes did not do this kind of abstraction so infinitely better there might be some justification for diverting the camera to the purposes of violent distortion.

Mr. Feininger is a practical man, and it is practical esthetics that he advocates. He says that his book is aimed more at the creative photojournalist ; then holds up as examples of creative photography the photogram, the double print, the solarized negative: performances that the photojournalist never gives. Maybe it is this practical foundation that leads him, in a book on the Creative Photographer, to omit or pass over lightly the work of such men as Paul Strand, Edward Steichen, or Alfred Stieglitz. He does observe that Edward Weston makes sharp prints. But he is always practical. He divides his book into five sections, not one of which is on the "mentals,” as Wilson Hicks would call them, of creativeness. We are given all the categories, but none of the inner workings; all the classifications but nothing of what goes on in a photographer during the creative act of twisting an image out of shape by manipulating the graphics. And also nothing about what goes on inside during the creative act of seeing. For all the many truths that the book gathers up again, the aspect of how the mind works when creating is missing. There is not a single touch of what Richard Boleslavsky conveys about creativeness in his FIRST SIX LESSONS IN ACTING. (This is a must for any photographer who would find out something about the mind when it creates and how to discipline it so that it can create. Terms must not be translated from acting to photography, but once done, every concept proffered applies. )

In all fairness to Feininger, we must realize that he thinks that he has caught the creative photographer in his net of outlines, definitions, and summaries—there is no doubt of his sincerity. Unfortunately, for all the traps, nets, and hooks, even the atmosphere of creativeness escaped him. He can not write the poetry required to convey it; and he does not consider that seeing; pure, raw, unmanipulated seeing such as Atget or Stieglitz did, or that a Cartier-Bresson or a Weston does is creative.

Since he says that henceforth we are to expect only picture books from Feininger, let us hope that they are all wonderful.

M.W.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

An Exhibition

An ExhibitionCreative Photography—1956

Spring 1956 By Van Deren Coke -

Photographing The Reality Of The Abstract

Spring 1956 By Beaumont Newhall -

Notes And Comments

Notes And CommentsSubjektive Fotografie 2

Spring 1956 By M.W. -

Notes And Comments

Notes And CommentsCreativeness In The Custom Processing Lab

Spring 1956 By Beaumont Newhall -

The Annuals

Spring 1956 By James S. Peck -

Editorial

EditorialThe Pursuit Of Personal Vision

Spring 1956 By Minor White

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

M.W.

Book Reviews

-

Book Reviews

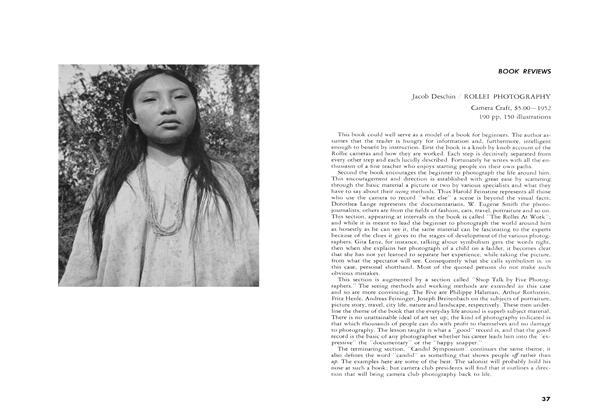

Book ReviewsJacob Deschin / Rollei Photography

Spring 1953 -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsOtto Steinert / Subjektive Fotographie

Spring 1953 -

Book Reviews

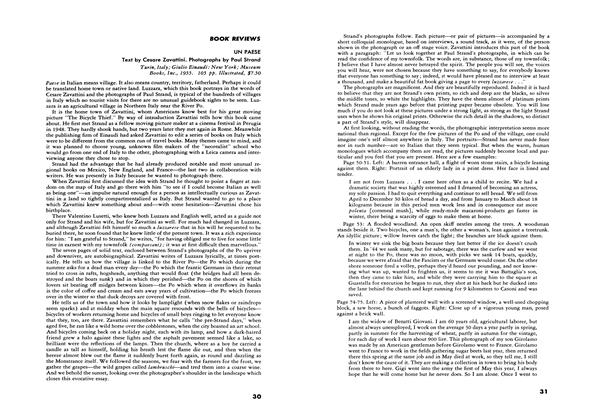

Book ReviewsUn Paese

Fall 1955 By Beaumont Newhall -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsBook Reviews

Spring 1954 By Byron Dobell, Minor White -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsZone System Manual

Fall 1962 By Gerald Robinson -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsA Dialogue With Solitude

Fall 1965 By Linda Knox