Book Reviews

Book Reviews

The Columbia Historical Portrait of New York

Spring 1954 Byron Dobell, Minor WhiteTHE COLUMBIA HISTORICAL PORTRAIT OF NEW YORK

BOOK REVIEWS

John A. Kouwenhoven

Doubleday & Co., New York, 1953. $21.00. 550 pp, 900 illustrations

This book is about the experience of change. More specifically it is about the changes that took place in a certain part of the world—New York City—and the changes in the way people have looked at that city from the time of its settlement in the seventeenth century.

The men who depicted New York in drawings, paintings and photographs were moved by several desires: sometimes simply to show its fortifications and navigable bodies or to append its image to a bottle of patent medicine; sometimes, more complicatedly, to flatter the city and, frequently, to shame it. No matter what the motive, the portrait has been attempted innumerable times and, because the subject is still alive, its final likeness is yet to be. So it is really a history of change rather than a demonstration of any singular, simple conclusion or series of facts that Mr. Kouwenhoven has presented to us. He has preserved the views of New York that have had meaning for its inhabitants in each age of its growth. He has also given us one of the most beautiful “picture-books” we are likely to see for many years.

But why should the historian be concerned with the pictorial at all? The question is not inconsiderable when one recalls that history, as we commonly understand it, is concerned to a large extent with written documents and events recorded by words. Nevertheless, there is great historical truth in pictures because images move us—they give pleasure and knowledge in that indelible fashion which tells us that some property of the real relation between subject and object has been conveyed; briefly, they light up the understanding.

It is important to recognize, of course, that very few single graphic images convey such a rewarding sense of depth and significance—only the greatest pictures have that power. The miracle of this book, then, is not in its “great pictures”—though some are magnificent—but, rather, in the historical fluidity achieved by selection and commentary. Kouwenhoven has once and for all raised the act of editing from the level (at best) of competence and taste to that of an art—one which might be called a legitimate child of history and poetry. In this note, however, we shall not burden Kouwenhoven with so much responsibility. Let’s say that he has performed his act of selection with the passion of the best kind of historian—man moved by a sense of the past. Each picture has been appraised with an eye to its relevance to his theme and to its connection with what has come before and what will come after.

The editor is not afraid to point, to digress, to discourse. Unlike the captions we are familiar with, with their machine-like punctuation of the obvious, he is not averse to talking of other things when he feels that they are relevant—however obliquely— to the pictures spread before us. Above all he has the courage and sureness that comes from a long acquaintance and unique sympathy with his subject. In this sense he is far beyond the realm of the usual harried “picture-editor” whose work is a series of compromises confounded with trepidation and a general sense of helplessness. Kouwenhoven does not snatch at the image; he conjures with it.

The format of the COLUMBIA HISTORICAL PORTRAIT is extremely simple. A running essay is printed on top of each page of pictures as a general discussion of what might be called New Yorkers’ visual attitudes towards their city. Printed beside the pictures themselves is a more detailed, very rich and specific description of the graphic images Kouwenhoven has gathered. The reason for the existence of the picture, its source, its creator and often why it has been chosen, are among the content of these captions. For once, these matters are not left to a reference in infinitesimal print or buried in some other part of the book. They are, as they should be, the essence of the historical portrait. For the whole point is exactly the picture’s identity. How else can we generalize about man’s history except from specific acts of intelligence?

For this reviewer, the running essay at the top of each page did not quite serve one of the purposes for which it was designed—that is, to be a means of helping the hasty reader keep track of what is being presented no matter where he opens the volume. I found that the fuller captions printed beside each picture held my attention much more effectively and that the running essay demanded more in concentration and time. I often lapsed in my reading of the essay or neglected it completely much as one does when skipping the sub-head on a newspaper story and going directly to the heart of the text. But this is not meant to deny that the essay is worth exactly the concentration which I neglected to give it. It is consistently brilliant, often poetic. That it has as much weight as it does on a first reading—considering the inevitable, almost overwhelming attractiveness of the pictures—should give some indication of its forcefulness.

One must, in conclusion, return to praise the sheer originality of Kouwenhoven’s eye; his uncovering of the space and forms of the city landscape during each era of its history. Although the photograph becomes the great recorder of the city in the 19th century, Kouwenhoven never tires of reminding us that it, too, is merely another means of showing us a particular man’s particular view of the world. Like all such views, of course, it may be very limited and mean. But at times it is as brave and grand as the strange skyscripers of Manhattan Island which, as Kouwenhoven concludes, “Against all logic, without anyone’s planning it that way... have become a symbol of man’s aspiration even though, like any towers man is likely to build, they stop well short of heaven.”

Byron Dobell

Jacob Deschin/35MM. PHOTOGRAPHY

Camera Craft Publishing Co., 1953, $5.00 192 pp, 115 illustrations

Jacob Deschin has performed a fine service to photographers in two of his latest books, ROLLEI PHOTOGRAPHY in 1952 where he set the style of book arrangement that he has followed in 35MM. PHOTOGRAPHY in 1953. In both Deschin takes the stand that cameras are instruments with which to make pictures. Obvious as this may sound he is one of the few manual writers to remember this truth and he has been rewarded with two sound and stimulating books. They make most of the similar books that have come out since read with resounding dullness.

Because of his stand the books are illustrated with superb photographs that are a pleasure to see as well as instructive. Some are by newcomers such as Zoe Lowenthal and others by the contemporary celebrities such as Cartier-Bresson and Eugene Smith. Also because of this stand the arrangement of photographs, captions, and descriptive material is such that the reader is confronted at once with 35mm. work at its best. The descriptions of the various miniature cameras how they are handled and operated are lucid as usual and sandwiched between examples of what this size camera can do in the hands of powerful photographers.

The chapter called “The Furtive Lens” puts into words what may well be the central philosophy of today’s miniature camera work. Here Deschin makes two points both of which are essential. In one place he says, “Once the 35mm. photographer has caught onto the idea that the candid camera works best in the role of shrinking violet, he will discover the means to use it that way.” While advocating the unobtrusive, he at all times warns against the excesses of the “candid” which in the past has so often violated human privacy. He makes this second point with words quoted from Roy Stryker, of Farm Security Administration fame, “I feel that it is not too much to say that the very future of the photograph as a social instrument is dependent on this single element: maintaining a basic respect for human dignity.”

The second point is brought home with his choice of illustrations. The pictures he has selected show that the photographers have learned to be “furtive,” have not invaded human privacy and at the same time have not lost intensity of image.

We might add in passing that to develop the discipline of the furtive camera the photographer has to learn to keep a very difficult balance between invasion and pictures that are interesting; fortunately he does not have to show the violations of privacy he has inadvertently made.

There is a subtle difference between the kind of picture made with the eyelevel camera and one made with a belt level camera—or so I have contended for a long time. Consequently I am delighted to find that a comparison of the pictures in these two books bears me out. The pictures made with the reflex cameras all have a quality of one angle of vision removed from reality whereas those made with the eyelevel camera have a quality of directness and subsequent intensity that seems to bring the spectator closer to the event. It always seems to me that looking down into a ground glass and around a corner with the aid of a mirror removes the photographer one dimension from the experience he is photographing. Thus he is forced into observing. With the camera at his eye he has more direct contact with the visual experience and is led into taking part in the experience.

Minor White

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

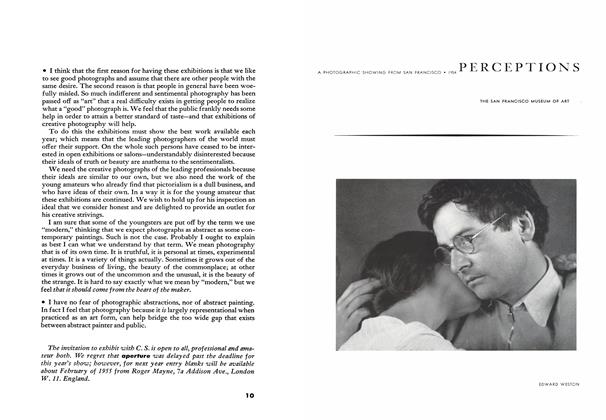

Perceptions

Spring 1954 By Dody Warren -

Rochester Photojournalism Conference 1953

Spring 1954 By Vincent S. Jones -

The New Realism

Spring 1954 By Derek Gardiner -

The C. S. Exhibitions

Spring 1954 By Roger Mayne -

Notes And Comments

Spring 1954 -

Editorial

EditorialNew Developments And The Creative Photographer

Spring 1954 By Minor White

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Minor White

-

Song Without Words

Winter 1978 By James Baker Hall -

Comment And Review

Comment And ReviewThe Photographer’s Eye

Fall 1967 By Minor White -

Light7

Summer 1968 By Minor White -

Octave Of Prayer

Fall 1972 By Minor White -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsThe Daybooks Of Edward Weston

Spring 1962 By Minor White, John Upton -

Editorial

EditorialAperture's Altered Format

Spring 1959 By Minor White, Shirley Burden

Book Reviews

-

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsRay Bethers / Photo-Vision

Summer 1957 -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsAnsel Adams / Artificial Light Photography

Summer 1957 -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsHenri Cartier-Bresson / The Europeans

Spring 1956 By M.W. -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsAndreas Feininger / The Creative Photographer

Spring 1956 By M.W. -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsAndreas Feininger / Advanced Photography

Fall 1952 By Minor White -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsThe Daybooks Of Edward Weston

Spring 1962 By Minor White, John Upton