Ten Books For Creative Photographers

1 THE NEGATIVE, BOOK 2, BASIC PHOTO SERIES

Summer 1956 Ansel Adams, Stephen Pepper, Gygory Kepes, Richard Boleslavsky, Brewster Ghiselin, George Boaz, Beaumont Newhall, Wilson Hicks, Heinrich Wolfflin, Evelyn Underhill, Minor WhiteTen Books For Creative Photographers Ansel Adams, Stephen Pepper, Gygory Kepes8 more ... Summer 1956

TEN BOOKS FOR CREATIVE PHOTOGRAPHERS

A critical list for the picture maker who is willing to read outside the field of photography.

The term "creative" has become as all embracing as its twin "documentary", and almost as diluted of specific meaning. Both of the words, like generous umbrellas, keep the rain off of a wide variety of mutually distrustful photographers. Consequently, "use the term with caution”, advises the wise man: but rather than use the word with the caution that it deserves we will use it rather loosely here—not to keep any form of creativeness out but to keep the transcendental forms of creativeness in. Thus "creative photographers” include the creative portraitest, the creative photojournalist, the documentarían (who insists that he is also creative), and finally the man who quietly persists in using the camera as a way of communicating ecstacy. These last, dedicated to releasing dreams in us, invariably strain the definitions of creativeness. Yet they are the ones to whom the term specifically applies.

Since we are not likely to agree on what a "creative photographer” is, a brief resumé of the kind of temperament found in creative people generally will augment our notions about him. He needs to have a temperament similar to that which makes a person turn to the arts. He will need to be aware that his photographs are outward manifestations of inner growth. He will need to consider that his practice of photographing is both an inward-going by which growth is nourished and an outward-going by which that growth is made visible. He will be more or less aware that that which grows in him is a soul. Whether or not he is afraid to admit this will depend on many factors, among them is the stature to which his soul has grown. If the photographer is well along he will not be afraid to admit it — for all his having more sense than to shove this glowing bit of sculpture into the hands of people who are all thumbs.

An artist, whatever his medium, functions as a whole, at least some of the time. Words, unfortunately, haggle ; they will not let us communicate a fused whole ; they force us to write about components. This list of books is aimed at the integrated workings of a creative photographer ; but in order to talk about it we will have to divide these workings in some manner. We will divide the fused working of a creative photographer into three kinds of craftsmanship: a craftsmanship of technique, a craftsmanship of design, and a craftsmanship of feeling. (The last is decidedly esthetic. ) Since three kinds of craftsmanship do not fit all the books included in this list, those that fall outside are included because we have found them important to our own thinking and found them invaluable in developing photography students at the California School of Fine Arts and at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

1 THE NEGATIVE, BOOK 2, BASIC PHOTO SERIES

Ansel Adams

A craftsmanship of technique means a working knowledge of all the graphics of photography and how to apply this knowledge appropriately. "Graphics” mean the physical and chemical properties of the medium: focal length of lenses, kinds of cameras, the properties of the films and papers available and the manipulations to which they are subject. "Appropriate application” means the use of the knowledge of the graphics based on a rapport between subj ect and photographer and what the photographer wants or must communicate or evoke in the audience. Actually this is a large order ; the photographer has to have a rapport in the first place, and in the second he has to face the welter of things that the graphics of photography can imitate with nothing stronger than his own integrity.

In photography a craftsmanship of technique is a bridge between the science of the medium, or sensitometry, and spirit.

To this end the zone system of Ansel Adams is the best to date. It is explained in various ways in all the books of the BASIC PHOTO SERIES (Morgan and Lester) but most explicitely in THE NEGATIVE*. The zone system is a method of tonal identification and a discipline of visualization whereby an imaginary print is mentally superimposed over a scene before the exposure is made. That is, before the negative is either developed or printed, the scene is previsualized in terms of the print. The zone system makes visualization a tool of seeing and previsualization a working state of mind for the creative photographer.

On the esthetic side the zone system is based on an assumption that the creative aspects of unique photography are centered in seeing. It provides the disciplines and working methods that aid such seeing : this as opposed to dark room manipulation. No one doubts the creativeness of the latter, but whether it is peculiar or unique to photography is open to question. The zone system for all its technical sounding terms is one artist’s contribution to seeing as the creative focus of the medium.

*A manual on the zone system has just been published by Morgan and Morgan reprinted from two articles on the subject that appeared in Yol. 3 of this quarterly.

2 THE PRINCIPLES OF ART APPRECIATION

Stephen Pepper

The second of the three craftsmanships designated earlier is the craftsmanship of design. This means a working knowledge of all the visual elements that function in photographs and how to use them to evoke or release emotional responses in the spectator. The visual elements are considered to be the illusions of light and space, the power of subject itself, the distribution of tones. A photographer who has acquired a craftsmanship of design can wield the power of visual tension, the vitality of visual contrast, the calm of visual similarities. He will also know how to tie up the loose package of a picture by balance. He will know when pattern is appropriate to the subject; and he will know when to impose his own idea of pattern on a subject and when to let a subject generate its own pattern. In either case he recognizes a successful weld between subject and pattern as design.

Of several books on the visuals of pictures Dr. Stephen Pepper’s PRINCIPLES OF ART APPRECIATION is exceptionally valuable to the photographer because it includes some of the reasons why we react to the visuals of form, color, pattern, mass, and the rest in the manner that we think we do. Both the findings of psychology on the subject of perception and the theories of esthetics are brought to bear on the subject of our reactions to what we see in pictures. The purpose is to develop taste and to unlock the treasures that artists have packed in pictures.

Dr. Pepper does not think highly of photographs, but his bias does nothing to prevent people from reacting to camera pictures in the manner he describes. The book will put a solid foundation under any photographer willing to study long hours to attain a craftsmanship of design. It is a mine of concepts and idea that will widen the horizons of any photographer and put the visuals of pictures at his finger tips.

3 THE LANGUAGE OF VISION

Gygory Kepes

Whereas Dr. Pepper takes a broad historical stand and looks at design in the light of contemporary research on esthetics, Kepes takes a narrow basis on design in his LANGUAGE OF VISION and extolls contemporary thought exclusively.

His functional esthetic is a consolidation of the experimental approach to visual art, often called the New Vision, that was codified and taught by the members of the Bauhaus group twenty years ago. Kepes explains how this approach disintegrated the meaning patterns of visual clichés into meaning facets and reassembled them in a new order. The necessity to do so represented a reaction on the part of a large segment of society to adjust to rapidly changing conditions. It was an attempt by art to catch up to the vivid advances of science and to reintegrate humans to a new world about them so that they could again live a rich internal life.

The New Vision when it is applied to photography is opposed to "seeing” as the creative focus of the medium, which Adams, for instance, practices and sponsors. The New Vision because it treats photography as a part of the language of vision and therefore contributory to a larger integration exploits the entire visual capabilities of photography without differentiating what is unique in photography from what is imitative. The LANGUAGE OF VISION displays the painter’s or hand artist’s use of photographic material and equipment. This is quite different than the use of the "graphics” by the photographer or camera artist such as a Weston or a Stieglitz.

It is something of a surprise to realize that Kepes considers advertising art as the goal of his language of vision. Fortunately he does so with idealism rampant and offers it as a challenge to the advertising world ; not only vitality for its primary purpose but with full recognition that advertising’s secondary responsibilities, its effect on popular taste, is proving to be more important than selling.

For the creative photographer the value of the book lies in the importance it gives to visual relationship as the fundamental exercise of seeing, the philosophy of integration, and most important the explanation of how the sense of movement in still pictures is a function of the mental activity that a picture causes in the mind of the spectator.

4 ACTING: THE FIRST SIX LESSONS

Richard Boleslavsky

The third craftsmanship is that of feeling and if a craftsmanship of feeling can be learned from books ACTING : THE FIRST SIX LESSONS is the book.

A craftsmanship of feeling means a working knowledge of technique and design applied specifically to the problems of evoking feeling and mood in people via the photograph. It also means a working knowledge of how to turn on and off, at will, a state of mind or an atmosphere of attention in which one can create. Finally it means a working knowledge of feeling as such. Boleslavsky presents all this in terms of the theatre and for the actor, yet nearly everything he says applies to the photographer. His chapters on observation, concentration, rhythm, with no more than rudimentary substitution of photographic terms for stage terms, reads as if written for photography.

Not only does he say that acting (photography) is the birth of the soul through art, but delineates the disciplines by which the growth of the soul manifests itself on the stage (photographs). How acutely he knows that the final product of the actor’s art is feeling aroused in the spectator. This takes place in the actor’s presence whereas in photography the photograph intervenes. The final product is ultimately the same, the experience of goodness, truth, or beauty by the spectator. The photograph has to speak for the photographer when he is not present. And all too often it mumbles when it should shout, garbles what is meant to be lucid.

The Six Lessons is mainly concerned with creativeness, and Boleslavsky knowing full well that when one tries to trace an outline around creativeness it politely steps out of the way. So he tells a story, proposes exercises, suggests disciplines by which a receptive state of mind can work. He sets the secret trap and goes off looking for four-leaf clovers. It is most important to note that when the trap is sprung—whether with a click or a bang—he does not look around but goes on looking for clover. Paradoxical as this may seem this is the manner in which one is caught in creativeness.

5 THE CREATIVE PROCESS

Brewster Ghiselin

A valuable companion to the Six Lessons is this anthology by poet and teacher Brewster Ghiselin. It includes a variety of what well known artists and scientists, poets and philosophers have written on their creative activities. Apparently the basic creative process is similar in nearly everyone for a basic pattern is traceable beneath as many variations on the theme as there are people. Temperament, profession, medium of expression and period all affect the outward manifestation; creativeness varies widely in intensity and still more in purpose, some purposes are slight, others nothing short of noble ; some persons feel that it comes from themselves and others report that they are only an agent for an outside force. The diversity is wide in the quoted examples. And probably any photographer can find here an example or two that parallels his own case. Certainly he can find affirmation for the unpopular ways of working which the creative person in any field must pursue.

6 WINGLESS PEGASUS

George Boaz

It is impossible to imagine how a man setting out to teach himself to be a creative photographer by reading can possibly start all three craftsmanships at once. Yet to explore the craftsmanships of technique and design and feeling all at the same time would be ideal. Obviously none of us are angels with three brains to read all three books at once ; obviously none of us go to a school to a teacher who presents a fraction of technique and design and the encouragement to make pictures within the scope of that fraction until we make a picture with a whole feeling. And that accomplished who will then repeat the process by uncovering a few more fractions of each ; and so on till we have mastered all three craftsmanships. That too would be ideal. However we reach it, integration of the three craftsmanships is ultimately necessary. Once fused one can live via the camera and film, and one’s photographs start to manifest the growth of the soul.

Make photographs then think about them; make more photographs in the light of what one has thought and then think again. This order and this rhythm is undeniably the best way of achieving the desired fusion of the craftsmanships. But the thinking process can stand some guidance. One’s own criticism of one’s own photographs is notoriously difficult—and the fault seems to lie with the honest enough, but still hindering conviction that "these photographs came out of the camera I purchased, therefore they are my own.” The attitude "my children—and therefore better than any one else’s children” is admirable in parents but a hinderance to the photographer trying to find out what goes on visually in his photographs, and trying to discover what effect they have on other people. Consequently any means, any conceptual tools to help in the analysis of one’s own work is invaluable, WINGLESS PEGASUS contains many such concepts for criticism and analysis. Analysis here does not mean a self analysis such as the psychologist gives or soul searching such as a young monk undertakes before confession, though perhaps not far from either. It means, in part, an answer to the question, "have I accomplished what I set out to do, or am I basking in the reflected glory of a happy accident?” It means contemplating your own photographs till you see what crept in when you were not looking; analyzing every inch of them till, no matter what someone else may find in them, you are not surprised at their findings.

The Boaz book is concerned with criticism and clearly reveals the narrow path that the critic must walk to avoid the pitfalls of the various kinds of fallacy, the impossibility of determining the artist’s intentions, the troubles one gets into when the photograph is used as a spring board into the wild blue yonder of the critic’s imagination. To divert the concepts included to the uses of the photographer takes considerable effort, but the widening of the photographer’s horizons and the sharpening of his powers of analysis is worth the effort. Considered opinion and refined perception is worth any effort.

While the value to the photographer contemplating his own work and learning to fuse the three craftsmanships is great, perhaps the book has even greater value to the future critic of photography. Who knows which young man or woman fascinated by taking pictures today will be tomorrow’s critic of photography ? Who knows which one has the capacity to look at other people’s photographs, not with the eye of the artist who, by nature, can only consider bad all pictures not done in the manner he would do them, but who can look at pictures as a teacher does, in the light of the progress of each student; or as the critic must, in the light of photography as a whole ; then in the light of art as a whole; and finally in the light of all of man’s picture making, regardless of medium. It is conceivable that the future’s great critic of photography will start with a camera.

7 THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY (2nd Edition)

Beaumont Newhall

If a study of criticism will broaden viewpoints and sharpen perception, a study of the history of photography will bring us in contact with the persons who have contributed to the course of photography and especially those who are responsible for the creative concepts found in the medium. These persons form a kind of family; a family of minds to which many of today’s photographers belong by spirit and temperament. Beaumont Newhall’s History serves the best to date to orient the photographer in search of his roots.

Unlike the standard histories which are chronological, loaded with raw material and comprehensive with undigested facts, Newhall’s book is compact, tightly and lucidly written; men’s lives are expounded in a phrase, their contributions to photography outlined in a succint sentence or a paragraph. He worked from the historical perspective, saw patterns and traced them. He digested the facts, sought the underlying concepts, and found that even in a brief century that traditions have developed. To name but a few, "portraits for the millions,” the "straight approach,” "instant vision.”

History presented in a conceptual manner enables the aspiring photographer to locate the traditions in which his personal talents can grow, his personal vision flower. When we talk to living photographers or read their credos, this is not the case. They are so immersed in their own personal vision (and rightly) they are so violently chipping at their own niche in a wild scramble of niche carvers that we are overwhelmed in a shower of marble chips—their vision and ours is clouded by the cloud of marble dust. Newhall’s view is concerned mainly with pictures and picture making acknowledging as he goes the science of photography upon which this is based. His History, therefore, fits the needs of the creative photographer exactly.

8 WORDS AND PICTURES

Wilson Hicks

Without realizing it we have probably given the impression that, for us, the center, the middle ground and the periphery of photography is the individual photographer in pursuit of individual aims. And further that the only possible goal is the single photograph that can stand strong, towering and isolated, scorning all help from either words or other photographs. Hence it is high time that we corrected this impression and consider the photographer when he works as a member of a team; and consider photographs when they work as units in a large whole, in either the picture story or in the sequence.

Let’s consider the photographer in a situation in which he must submerge some part of his personal aims ; or, and preferably, let’s consider him wishing to contribute to a larger whole than any one man alone can achieve. This has its creative aspects. Today’s mass communication by word and picture is made possible by men who so wish. And it is through teamwork that a form is created that is big enough to catch up photography, and writing as well, in its flowering.

So far no one has explained better than Wilson Hicks in his book WORDS AND PICTURES the workaday functions of a team that includes the photographer —and the creative interplay of the photo journalistic team. He takes the mechanics of picture making for granted in order to devote space to the "mentals,” as he calls them, of photojournalism. These include the relationships of team members to each other; the production of many photographs that will, rather than stand alone, fuse into the picture story; and words and pictures, not as merely explaining one another, but as wedded to each other. Best of all he treats the fusion of words and pictures as a new medium.

Hicks, like the rest of the authors in this list of books, provides concepts rather than "how-to’s.” His "mentals” are tools by which an aspiring photographer can learn to cope with any situation—as contrasted to rules that fit a limited number of specific situations. With conceptual tools the photographer can turn whatever comes his way to creative uses.

9 PRINCIPLES OF ART HISTORY

Heinrich Wolfflin

In the PRINCIPLES OF ART APPRECIATION Dr. Pepper discusses the basic elements of pictures. He is concerned with the elementary visual such as line, mass, color; he is also concerned with preliminary fusions of these elements such as pattern. A knowledge of these is necessary to the photographer if his perception is to be heightened. But the photographer must always work with a viewfinder full of visuals fused into a whole, and furthermore with today’s techniques speed of seeing gets the picture. Hence any means to help him quickly grasp whole sections of his potential picture, or any means by which he can gain a near-instinctive grasp of the picture as a whole is eagerly sought. Fusions of more elements than Pepper provides will be to the photographer’s distinct advantage. Wolfflin’s visual concepts are to the point: they help because they fuse several visual elements into one rapidly understood feeling. His concepts of light and space for instance can be used to develop a speed of seeing in the photographer that approaches what appears to be instinctive.

Wolfflin’s only concern with photography is as a means of copying the paintings, sculpture and architecture of the 16th and 17th centuries around which his discourse centers. Consequently it is a little taxing to turn the concepts, by which he isolates the contrasting styles of two separate centuries, to the uses of the practicing photographer. It is easy enough to understand how a photographic historian might use these concepts, but a little hard to see how they apply to the cameraman. But it can be done. Under guidance, students at the California School of Fine Arts during 1947 to 1952 developed for their own use highly pertinent concepts out of Wolfflin’s concepts for art.

The modified concepts were used for more than the speed-up of perception in fast moving situations, they were put to use as a vocabulary by which prints might be "read.” This means that the concepts were so used that the student could participate in a photograph by a form of analysis. And finally they were used to analyze style in photographs. This is more in acccord with Wolfflin’s original purpose and introduced the rarely undertaken practice—rare in photography that is—of discerning photographic style.

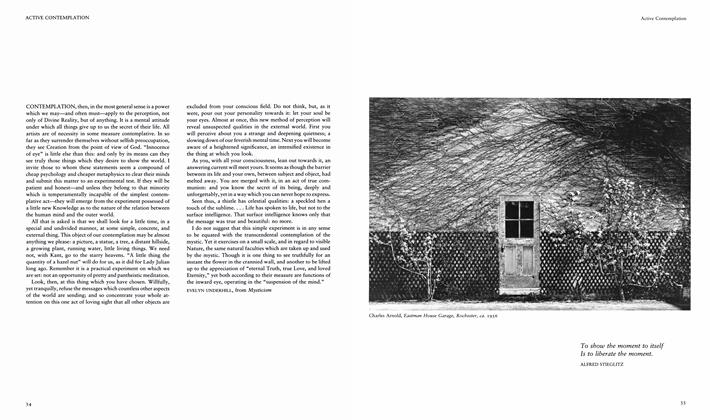

10 MYSTICISM

Evelyn Underhill

MYSTICISM applies only to such dedicated cameramen as try to make the medium of photography communicate ecstacy.

Evelyn Underhill throws over all concern for the visuals of the world of appearances for the unvisuals of the invisible world of Reality. In so doing, especially in the first third of the book, The Mystic Fact, explains that it is the element of mysticism that animates all artists, poets, creative scientists and intuitive philosophers. And so far as photographers are artists by temperment, poets by inclination, scientists by habit, and philosophers by intuition they too will have some contact with mysticism. Might it not be just this spark of the mystic (the term is used here in its best sense) that identifies the "creative” photographer? At any rate some photographers push the medium of photography to every extreme it has to communicate ecstacy. That photography does this lamely and inadequately is a fault common to all art media. All words, all images, all sounds flounder when they are given the burden of communicating, evoking or releasing matters of the spirit.

Anyone wishing to get an insight into the creative process, its awakening, its growth, its rises and falls, its fluctuations and its flowering this is the book to read. It is concerned with the mystic, but applies to everyone. Any photographer who has digested all the other books in this list and turned their various aims to his own purposes will have no trouble with this one. As Underhill says, "I do not care whether the consciousness be that of artist or musician, striving to catch and fix some aspect of the heavenly light or music, and denying all other aspects of the world in order to devote themselves to this : or of the humble servant of Science, purging his intellect that he may look upon her secrets with innocence of eye: whether the higher reality be perceived in the terms of religion, beauty, suffering: of human love, goodness, or of truth. However widely these forms of transcendence may seem to differ, the mystic experience is the key to them all.”

M. W.

Doubtlessly others with an abiding interest in creative photography have found still other books which are pertinent. We would like to hear about them. It has been difficult to omit Bernard Berenson’s AESTHETICS AND HISTORY in the present list, and maybe it should have been included. We will be grateful for other suggestions, especially if brief resumes are included and why the book seems pertinent to the reader.

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Ansel Adams

-

The Profession Of Photography

Winter 1952 By Ansel Adams -

This Is The American Earth

Summer 1955 By Ansel Adams, A. J. Russell, Philip Hyde, 2 more ... -

Western Influence

Western InfluenceWestern Influence

Summer 1984 By Isabel Kane Bradley, Ansel Adams, Barbara Morgan -

The Workshop Idea In Photography

Winter 1961 By Ruth Bernhard, Minor White, Ansel Adams, 2 more ...

Beaumont Newhall

-

Letters To The Editor

Letters To The EditorLetters To The Editor

Fall 1959 -

The Stuttgart 1929 Exhibition

Summer 1955 By Beaumont Newhall -

Photographing The Reality Of The Abstract

Spring 1956 By Beaumont Newhall -

Notes And Comments

Notes And CommentsCreativeness In The Custom Processing Lab

Spring 1956 By Beaumont Newhall -

The Education Of Picture Minded Photographers

The Education Of Picture Minded PhotographersTeaching The History Of Photography

Spring 1957 By Beaumont Newhall -

On George Eastman House

Spring 1959 By Beaumont Newhall

Brewster Ghiselin

Minor White

-

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsAndreas Feininger / Advanced Photography

Fall 1952 By Minor White -

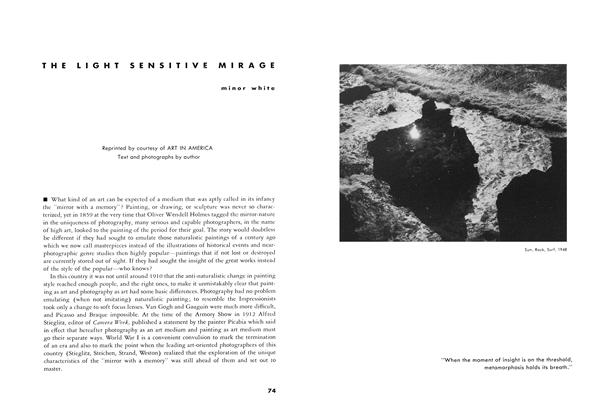

The Light Sensitive Mirage

Summer 1958 By Minor White -

Editorial

Winter 1959 By Minor White -

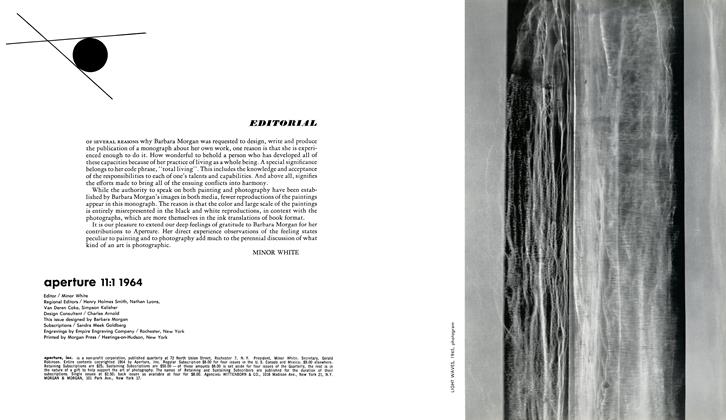

Editorial

Spring 1964 By Minor White -

Book Reviews

Book ReviewsVision-Value Series

Fall 1965 By Minor White -

The Workshop Idea In Photography

Winter 1961 By Ruth Bernhard, Minor White, Ansel Adams, 2 more ...