THE NEW REALISM

derek gardiner

Reprinted by permission of PHOTOGRAPHY (London)

By its very nature, photography is harnessed to reality for, to take a photograph, you need an object. Yet, from the first, there have been photographers who were fascinated by romantic ideas. Some periods have favored the growth of such romanticism, others the ascendancy of realism.

A realist photograph treats its subject as a fact; it is crisp and objective and requires the subject to speak of itself and for itself. A romantic photograph uses the subject as a vehicle for conveying an emotional idea, and has a greater emotional potential than normally belongs to the subject itself. At its worst, romantic photography leads to that odd pastime, “fancy dress” photography.

Julia Margaret Cameron’s portraits were very different from the commercial portraiture of her time, in which the sitter was glamorized by the addition of the ornate background and much bric-a-brac. Both were the product of Victorian Romanticism. Mrs. Cameron shunned such absurdities. She draped many of her sitters in dark velvet to conceal their workaday clothes and, according to her son, “when focusing and she came to that which was beautiful to her, she stopped there, instead of screwing on the lens to the more clearly defined focus . ..” In her illustrative tableaux for THE IDYLLS OF THE KINGS her romanticism ran wild and produced photographs that can only be considered lamentable errors of judgment.

Although Mrs. Cameron was subject to the fashionable excesses of her time, many of her portraits have, nevertheless, an enduring quality that is beyond fashion.

This reveals one of the greatest dangers in wait for the romantic artist. In every period, one particular manner or aspect of vision will have the most compelling appeal. Naturally the more adventurous photographers will find themselves working within the spirit of their time. For the great photographer, as well as the merely talented, this spirit will be the same and to their contemporaries it may be difficult to separate them. But in time, when fashion has changed and the older manner seems only a dated curiosity, it will become evident that the great photographer has merely used the manner as a vehicle for a way of seeing that transcends the fashionable and one that would seem impressive at any time.

The tradition of realism from Fox Talbot’s calotypes of Lacock Abbey onwards is little concerned with fashions of the spirit. Clothes change, buildings are erected or destroyed, institutions wither away and the realist photograph remains as an objective historical document.

Because the realist must often catch life in its passage, this aspect of photography could not develop fully until emulsion speeds had become sufficiently fast and readily portable cameras were available. Prior to this, realist photographs were often architectural subjects and figures were few, or even posed. With the introduction of the first Kodak camera in 1888, the tripod could be discarded and the camera go out into the everyday world.

Paul Martin in England with his omnivorous desire to record life directly was the immediate precursor of LIFE and PICTURE POST photographers. Indeed, the birth of LIFE in 1936 and that of PICTURE POST two years later might seem to date the coming of age of such realism; but in fact they merely followed a movement already well established.

During the depression in America, The Farm Security Administration employed a group of photographers, amongst whom was Walker Evans. These photographers went out to the bread lines and the Dust Bowl, bringing back photographs that showed a new and more vital realism. They set out to record significant reality, and they were not concerned if the subjects they found did not conform to the official canons of pictorialism.

This new interest in the realism of everyday life as opposed to the realism of the sensational was to be found elsewhere. In 1929 at the big German Werkbund exhibition, FILM AND PHOTO, police record photographs were hung beside the photograms and abstract details of the New Photography. The impact of the economic collapse was everywhere destroying the avant guarde of the twenties, which had been preoccupied with experiment and abstraction. Photography was being put to work for its existence. In this perspective, the foundation of LIFE and PICTURE POST can be seen as the consolidation of a movement that swept through the thirties and reached its highest point during the years of the second world war.

• For the most part, this realism conformed to our definition—it was objective, factual and documentary, but in the work of a young photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson, who began to exhibit during the early thirties, there was a new and disturbing element. His work was certainly documentary in the sense that it was of real people going about their business, but there was a curious ambiguity. For two or three years, the inhabitants of his photographic world seemed to live in a stranger and more fearful existence than any we know.

It is disturbing to look at a collection of these early photographs. A father clutching his son to him, dirty and emaciated, stares up at the camera that looms over him as if it were a thing of infinite menace. A child stumbling along a wall presses himself against it as if seeking to draw security from the stone. It would seem that Cartier-Bresson was influenced by Surrealism at this time, and yet Surrealism was a characteristically Romantic movement. So we have an odd state of affairs in which a documentary photographer draws from real life scenes that are romantic in spirit. That was only a passing phenomenon of Cartier-Bresson’s work, which subsequently became more deeply humanistic, and the impulse was lost in the documentary period of the late thirties and war years.

When the war ended, photographers (many of whom had been working in the armed forces) faced the problem of adapting themselves to the realities of peace. But, beside their personal problems they also had to adapt their vision to the new pattern of life that was emerging. Gradually certain tendencies became clear. The Combined Societies group was formed in 1945 to encourage the inventive and direct uses of photography —abstraction, documentary, experimental—all were welcome. In Germany and Switzerland a group of young photographers exploited pure photography under the group name of Fotoform. Around Dr. Steinert of Saarbrücken there grew up the Subjective Photography group.

In all of these movements two tendencies predominated—the abstract and the creative use of reality. The abstract photographers are doubtless influenced by the widespread growth of abstract painting. Their work is largely a continuation of certain aspects of the New Photography of the twenties pioneered by Moholy Nagi, Man Ray and others: more complex, perhaps, but not essentially different. Contrary wise it is in the use of reality that some contemporary photographers are finding their new directions. [Alvin Langdon Coburn was making “abstract” designs of the Grand Canyon as early as 1910; and Paul Strand’s abstractions were published in CAMERA WORK in 1916, and ought to be listed among the pioneers. Editor’s note.]

• This trend and its characteristics are now sufficiently well developed to be termed The New Realism. Prior to the second world war, the documentary tradition was well established in photography. It was essentially one of social realism. But after 1945 the impetus of documentary had spent itself, and certain photographers began to look at reality more closely. During the war, the individual had been all but lost in the anonymity of uniform and group action. In peace, the importance of the individual reasserted itself once more.

Because the human personality is a complex of many opposing stresses, held in dynamic balance, the photographs of the New Realists became perceptably less objective. It was to people in the surroundings of their daily lives that photographers looked when they came to reassess reality. More than this, they searched for and found the individual as a personality, not merely the person as a reflection of social conditions. So we have the anomaly of a movement that seems to look into reality so closely and intensely that it pierces the outer layers of appearance and reaches beneath to the subjective, and so romantic, photograph.

The trend is well illustrated in this year’s PHOTOGRAPHY YEARBOOK (London). [The 1953 American annuals also display the trend as well as most of the photographs in aperture.] Look at the work of Boubat, Dieuzaide, Steinert, Pal Nils Nilsson and the new photographs by those older masters, Renger-Patzch and Adolf Lazi. Here we are conscious of living personalities in all their complexity and ambiguity. In all these photographs the emphasis is not on people, but on one particular person.

With Dr. Steinert’s photograph of a young woman we are in a different emotional climate. Dr. Steinert is on the far left flank of the New Realists, as befits the prophet of Subjective Photography. In his photograph, the mouth and eyes, wrinkled forehead, broken chairback and the pose all combine to generate an atmosphere charged with ambiguity. We are conscious of a personality: but on consideration we come to realize that this might not be the girl’s true character at all. This could be a projection of the photographer’s idea, veneered over reality. This is no derogatory criticism. Rather we must admire Dr. Steinert’s skill in realizing his conception. Remembering Mrs. Cameron, we can see what dangers threaten anyone seeking to make photographs reflect our contemporary romanticism.

We who live in a climate of cold war and existentialism are peculiarly susceptible to the romanticism of seediness and uncertainty. But in a generation or two, only great creative works cast under the sign of our post-war uncertainty will survive. The remainder will be curiosities like the Pre-Raphaelitism of Mrs. Cameron. If the new realism is to avoid the fate of such romantic excesses, it is clear that it must not stray too far from the world of appearances that we ordinarily call reality. Its greatest contribution could be the personalizing of the documentary tradition in photography. If it fails, it will merely reveal a romantic gloss on contemporary life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

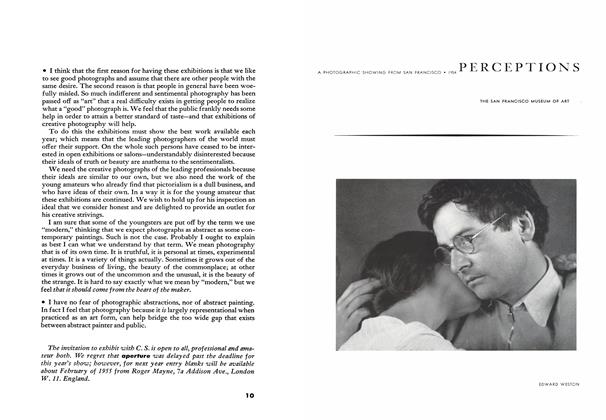

Perceptions

Spring 1954 By Dody Warren -

Rochester Photojournalism Conference 1953

Spring 1954 By Vincent S. Jones -

The C. S. Exhibitions

Spring 1954 By Roger Mayne -

Notes And Comments

Spring 1954 -

Editorial

EditorialNew Developments And The Creative Photographer

Spring 1954 By Minor White -

Why Aperture Is Late

Spring 1954