In the Studio

Since the invention of the medium, photographers have trained their cameras on art objects and artists.

Brian Dillon

AMONG THE FIRST THINGS PHOTOGRAPHERS GHOSE to do with their new medium was train it on images and works of art. Before he composed his View from the Window at Le Gras (ca. 1826)—sometime contender for the first photograph from nature—the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce had made heliographic reproductions of engravings showing a man and a horse, a woman at a spinning wheel, and Pope Pius VII. A decade later, Louis Daguerre photographed a sharply lit arrangement of plaster-cast sculptural fragments and a framed picture. The Artist’s Studio (1837) spawns a genre: the photographic study of workspace, materials, inspiring artifacts, and (whether or not the artist is seen) creative presence. In Daguerre’s image, the studio is already a fantasy, its putti and idealized nudes, its wine flask suggestive of artistic or poetic ecstasy a la Keats—“Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene.” Is it significant that in this studio, real or imagined, no actual artwork is being made?

In some ways, the photograph of the artist and their studio has not altered substantially since the decades of Nidpce, Daguerre, and Hippolyte Bayard. Especially when it comes to painting and painters—the studio as scene of sudden epiphany and protracted labor; a fascination with materials, tools, and surfaces; the creative power of the artist expressed in the body or the gaze, or somehow from the space itself. Fame, too, and the sense of career, reputation, adventure for both the photographer as well as the painter (the teenage Stephen Shore photographs Andy Warhol and the Factory milieu, learns all about aesthetic judgment and hard work). But much else may happen in the encounter. Here are six historical and contemporary views of the photographer’s studio visit and the vision it frames of the artist.

A prime motive for the photographer in the artist’s studio: to picture thought, which is distinct from the wild eye of inspiration.

1 Portrait of the artist as an artist, “X gentleman in every way,” claims a handwritten caption to a more or less randomly chosen record, from the Frick Collection, of how the late nineteenth century liked to picture a painter. The date is in the late 1880s, the photographer is possibly one Edouard Fiorillo, and the sitter is Edwin Lord Weeks, contriver of lavish orientalist fantasias, in his Paris atelier. Two massive canvases dominate the photograph, on one of which we are led to believe the painter is at work. Behind Weeks are more paintings, a wall of hanging carpets, and, at his feet, the splayed skin of a tiger. It’s a grandiloquent example of a Victorian photographic type: the modest painter posed thoughtfully with his palette, while around him his salon-hung works and ornate furnishings project his status.

Of course, Weeks is depicted pretending to be a painter, as in a way they all are. But the conventions of this act will change in the following decades. Above all, the artist starts to embody or perform, often in close-up compositions, what the photographer considers to be characteristic of the art itself. At a far remove from the formal portraits of the nineteenth century, but still in thrall to an ideal of masculine creative mastery, there are Bruce Bernard’s twentieth-century photographs of the painters Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, and Francis Bacon—each a fierce, heroic, or melancholy embodiment of the main features of his art. Each one, also, an almost parodic expression of the same: the flinty stare of Auerbach, Freud’s intensity slightly blurred into movement, Bacon slouching in his leather jacket.

2 Solitude and spectacle. A simple, dumb fact of the portrait in the studio: The painter cannot paint while looking at the camera. And yet what the photographer wants, especially in documentary or journalistic situations, is to be able to see, at the same time, the artist’s gaze and the work itself being made. It is a fiction that easily translates into spectacle, photographic or filmic. The mythology of Picasso in his studio had long been established—including by Dora Maar’s photographs and the artist’s own—when, in 1950, Paul Haesaerts’s short film Visit to Picasso framed him painting on glass while facing the camera. The following year, Hans Namuth’s Jackson Pollock 51 showed the painter at work on a horizontal, four-by-six-foot sheet of glass, while the filmmaker lay underneath with his camera. The final day of the shoot is said to have unsettled Pollock, who felt he had exposed too much; he started drinking again after two years of being sober.

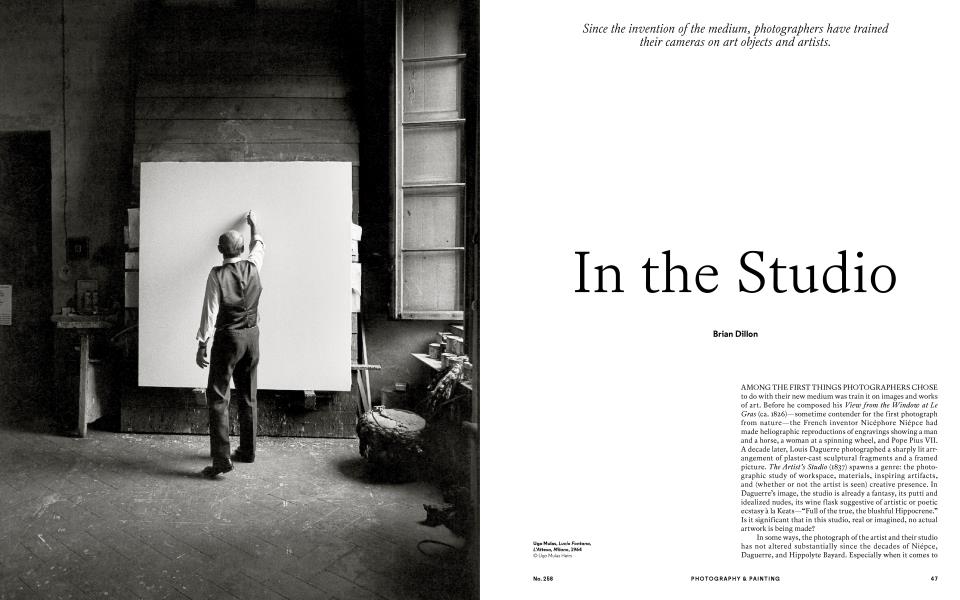

Alongside or against the spectacle of the painter in action, there is the more ascetic image of the artist making, or about to make, a single gesture. There are, unsurprisingly, many photographs of Lucio Fontana puncturing canvases: a frenzy of poking, stabbing, and slashing motions played out jocoseriously for photojournalists. The image that best captures the austere adventure of the cut is from a series taken by Ugo Mulas in 1964. In other pictures from this session, we see Fontana from the side, blade in hand and raised; in another, he is midslice. But in the most striking image, the canvas is the pale center of a mostly black, faintly window-lit scene. Fontana adopts the same raised-arm pose as elsewhere, but this time his back is turned toward us—we’re no longer marveling at the performance but accompanying the actor in a solitary and decisive instant.

3 How to photograph a thought. Toward the end of Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes is thinking about the look of the photographed being when he asks, “How can one have an intelligent air without thinking about anything intelligent, just by looking into this piece of black plastic?” Though Barthes does not discuss it, the accompanying image is André Kertdsz’s 1926 portrait of Piet Mondrian in his studio. Everything around the painter conspires toward an impression of the customary lines and planes of his art. The edges of paintings, corners of the room, even Mondrian’s toothbrush moustache and the grids that make up his wicker chair all tend to a perpendicular trimness and harmony. As Barthes notes, however, it’s the artist’s gaze that holds us, even though he might be thinking quite un-Mondrian thoughts. A prime motive for the photographer in the artist’s studio: to picture thought, which is distinct from the wild eye of inspiration, from the action of painting itself, from sedulous mark making or passionate sweeps.

4 The things themselves. In 2011, Tacita Dean made Manhattan Mouse Museum, a sixteen-minute film in which Claes Oldenburg lovingly tends to and carefully dusts curios on the shelves of his studio: empty perfume bottles, toy automobiles, fake fruits, twin dandified figures of Mr. Peanut—a cabinet of curiosities, a collection in nuce of Oldenburg’s own subjects and sensibility. Manhattan Mouse Museum depicts the attention the artist lavishes on things near at hand and recalls the familiar (especially to the critic) studio-visit urge to examine for clues the objects and detritus that surround the artist, in the conviction that person and space are part of the same desiring and creating machine.

At two key moments in his career, Cy Twombly was the subject of an experiment concerning the intrusion of photography into the artist’s studio. Could photographs properly represent the ethos and aesthetic of a painter, or would they always compromise the art and the artist with an excess of style and legend? In 1966, American Vogue ran “Roman Classic Surprise,” an article about Twombly written by Valentine Lawford with luxe color photographs by Lawford’s partner, Horst P. Horst. The photographer captures Twombly lounging in a white suit in his Roman palazzo, surrounded by exquisite lumps of classical statuary, pale gilded furnishings, artworks by Picasso and Gerhard Richter, streaks and daubs of pigment on his studio walls. And in the distance, framed by a marble doorway, the artist’s wife, Baroness Tatiana Franchetti. The import of the whole spread of text and image—outtakes from the series were published by Nest magazine, in 2003, confirming the effect—was to hint broadly at Twombly’s bisexuality and to celebrate the ornamental aspects of his art. Neither was a reputable inference in 1966, but as the writer Pierre Alexandre de Looz has pointed out, in retrospect, Horst’s photographs affirm a real affinity between the pleasures of abstract art and the rigors of interior decor.

Twombly had left the United States for Italy in 1957. In the early 1990s, he began returning to Lexington, Virginia, where he was born, and set up a studio there. He had known the parents of the photographer Sally Mann since he was a teenager; they were among his first collectors. In 1999, Mann began photographing Twombly’s studio and carried on until shortly before his death, in 2011. In these photographs, the painter is not present, and so much depends upon the juncture of studio wall and studio floor—the seam over which spills the evidence of the painter painting. Streaks of yellow and lavender pigment drip from a painting onto the wall below and, in turn, spatter the newsprint laid on the ground. Two dozen saturated rags form their own sort of composition, a luted floral arrangement of mint green, mustard, terra-cotta, crimson, wine, mauve, and ice cream white. In some photographs, there is just the play of light on bare studio walls, rhyming with Twombly’s own marks and faintly suggestive of time slanting through the space.

5 An absent god. Of course, the studio photograph without the artist can be anarchic instead of serene. For example, the drifts of paint and printed source materials in the photographs Perry Ogden took of Francis Bacon’s London studio, in 1998, before its removal and reconstruction at the Hugh Lane Gallery, in Dublin. Or Ugo Mulas’s high-contrast study of Robert Rauschenberg’s studio floor in 1965, showing a mass of materials overseen by a lounging dog.

When the artist is no longer there at all, the space can easily become a museum, a site for veneration or relic mongering unless released by the photographer’s estranging intimacy with what remains. In 1989, Luigi Ghirri met the executor of the estate of Giorgio Morandi and, subsequently, visited the late painter’s studio in Bologna over a period of six months, taking around four hundred photographs. Ghirri’s pictures possess the restrained tactility of Morandi’s still lifes. Bottles and vases and other vessels crowd on tables, sometimes solidly, sometimes nervously approaching various edges. The windows are thrown open, flooding the white room so that all these teeming artifacts and the furniture that contains them threaten to pale and fade in the light. In the image that most obviously invokes the absent painter, an easel stands empty but around it teems the residue of a life’s work: pots and brushes and neat stacks of books.

Morandi’s studio remains a source of fascination. In 2020, the American photographer Mary Ellen Bartley—whose meditative images of books and libraries have included the collections of Pollock, Robert Wilson, and the Grey Gardens house—was on a residency at Casa Morandi, photographing the artist’s library, when the pandemic intervened. Taking the images she had made back to her studio in Sag Harbor, New York, Bartley began to append to the photographs opaque or semitransparent veils, producing montages that mimic Morandi’s work but also place it, and him, at some obscuring remove. Bartley’s tools include the celluloid grid Morandi used to compose his own paintings, but it’s unclear if we are being invited to see as the painter saw or to submit ourselves to the gaze of his world reflected back on us.

6 The studio is a time machine. The studio is a self-enclosed space that’s also a portal into elsewhere for both the artist and the visiting photographer, transporting them to other places and times. Perhaps this becomes truer the longer the artist has spent in the studio? In certain cases, instead of becoming solidified in the space, the older artist’s studio seems to bristle with objects, images, and adventures from somewhere else. In 2011, Agnes Varda made a nine-minute film at the studio of her friend Chris Marker. The space is a storehouse of books, magazines, toys, films, videos, and generations of cameras, computers, and other technology. Marker seems to live inside the museum of his own past—except that he has not stopped working, has never ceased paying attention to the world. In what is, oddly, the film’s most moving scene, he shows Varda his cell phone, onto which he has downloaded titles by some of his favored writers: Guillaume Apollinaire, Louis Aragon, the memoirs of Franpois-Rend de Chateaubriand. A digital toolbox to help him speed into the future.

The studio is another sort of time machine too: a mechanism for storing up intimacies between painter and photographer. The photographer Collier Schorr and the artist Nicole Eisenman have known each other since 1987; when they first met, they were struck by their physical resemblance. Over the years, Schorr has written about Eisenman’s work and also photographed her for the likes of the New York Times and The New Yorker. Since 2020, Schorr has been drawing her friend, based on photographs, many of them taken in Eisenman’s studio, which is still present in the form of easels, possible edges of canvases, paint-spattered clothing, and studio-grade footwear. In her essay that accompanies COSMOS (2024), Schorr’s recent book of these drawings, the critic Jennifer Higgle writes: “In our hyper-accelerated age, the act of drawing is a way of slowing down. Unlike a camera, whose work is done in the blink of an eye, a pencil will not be rushed.” True, no doubt—except that the COSMOS drawings’ accumulated moments of looking at photographs extend the afterlife of the photograph, acknowledging that it’s also a form of prolonged and even loving concentration.

Brian Dillon’s most recent book is Affinities: On Art and Fascination (2023).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

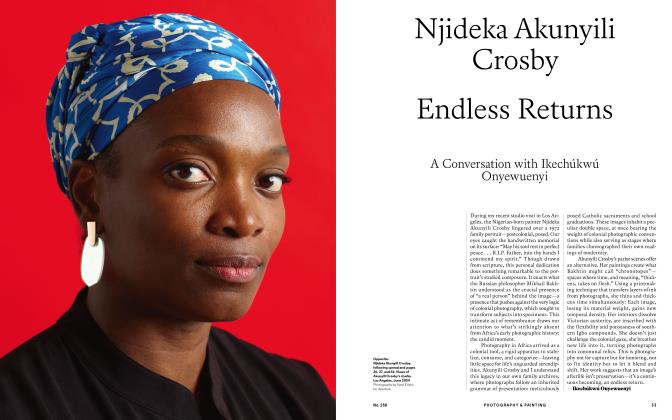

Njideka Akunyili Crosby Endless Returns

SPRING 2025 By Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi -

Vija Celmins The Surface Of Things

SPRING 2025 -

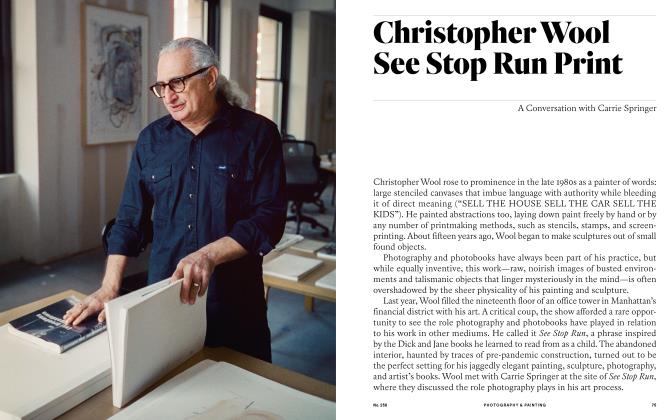

Christopher Wool See Stop Run Print

SPRING 2025 -

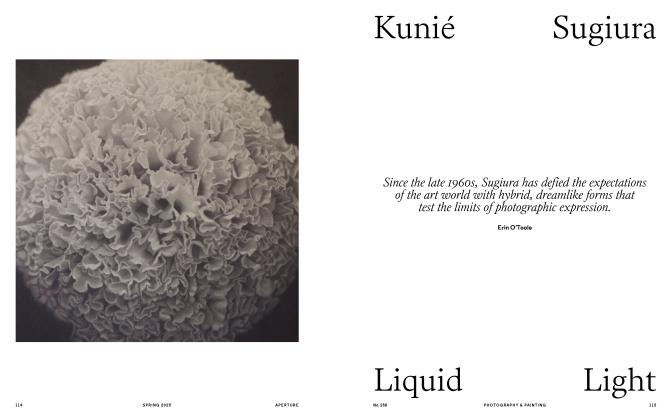

Kunié Sugiura Liquid Light.

SPRING 2025 By Erin O'Toole -

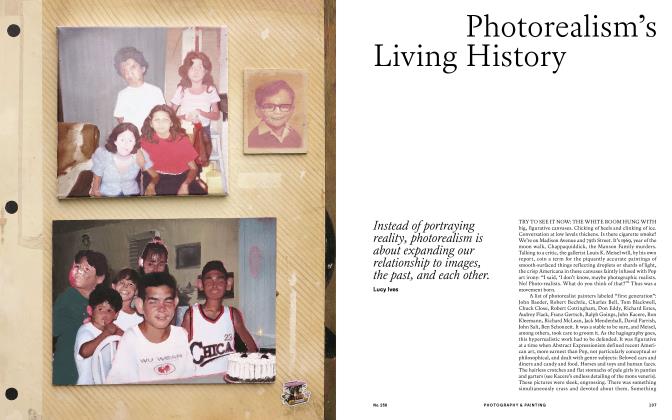

Photorealism's Living History

SPRING 2025 By Lucy Ives -

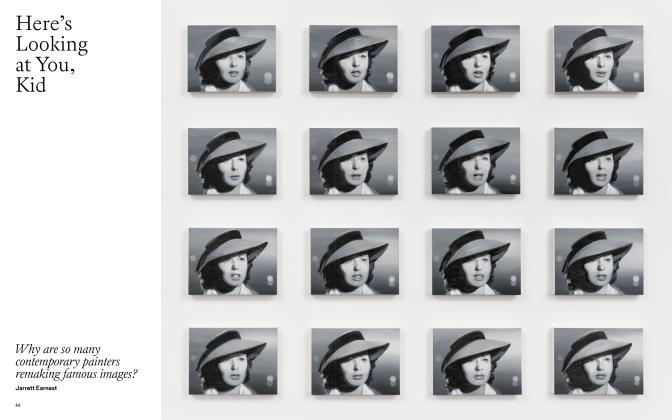

Here's Looking At You, Kid

SPRING 2025 By Jarrett Earnest

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Brian Dillon

-

Work In Progress

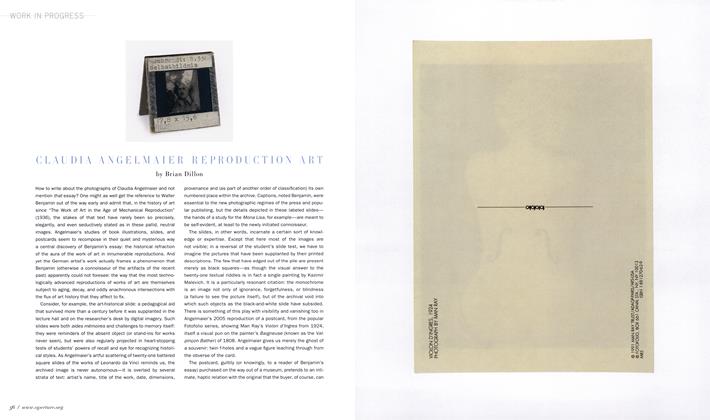

Work In ProgressClaudia Angelmaier Reproduction Art

Fall 2008 By Brian Dillon -

Reviews

ReviewsPhotography Degree Zero: Reflections On Roland Barthes's Camera Lucida

Spring 2010 By Brian Dillon -

Work And Process

Work And ProcessAn Atlas Of Decay: Cyprien Gaillard

Fall 2011 By Brian Dillon -

Words

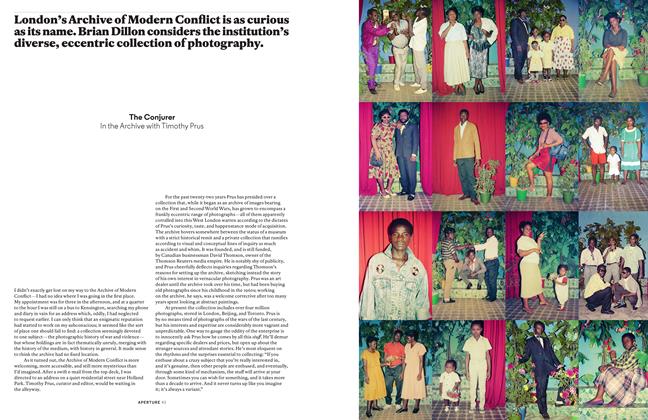

WordsThe Conjurer In The Archive With Timothy Prus

Winter 2013 By Brian Dillon -

Pictures

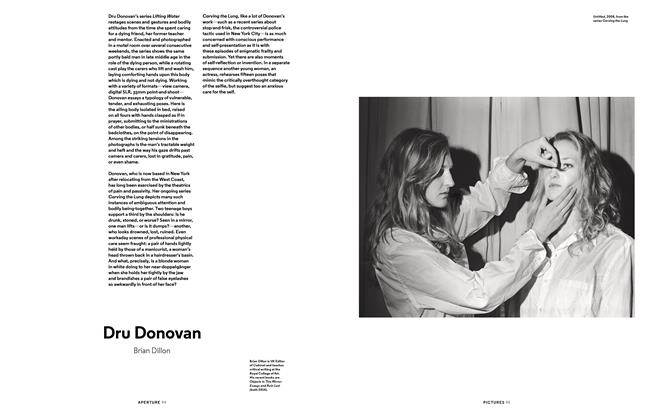

PicturesDru Donovan

Winter 2015 By Brian Dillon -

Preview

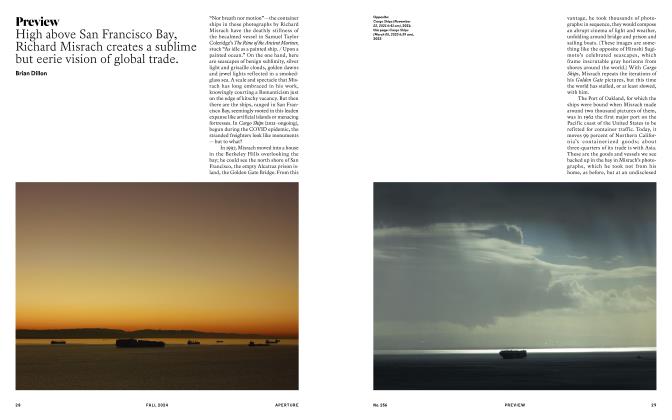

FALL 2024 By Brian Dillon