THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

Called To The Camera

Spanning more than a century, a new book reveals the inner workings of Black portrait studios.

FALL 2023 Salamishah TilletCalled to the Camera

Spanning more than a century, a new book reveals the inner workings of Black portrait studios.

Salamishah Tillet

These days, I spend a lot of time in the recently restored Hahne & Company building in downtown Newark, New Jersey. Home to Express Newark, the center for socially engaged art and design that I currently direct, it was abandoned for nearly half a century before being renovated into a hub for everyday Newarkers to meet up, shop, or get their picture taken at our Shine Portrait Studio. Founded in 1858 as the city’s first department store, the building is remembered by many African American residents—like my grandmother, who migrated here from North Carolina—as a site of racial discrimination akin to, in many instances, what they long experienced down South. “We didn’t shop at Hahne,” my grandmother often said. Referring to its competitor around the corner, she’d add: “We only went to Bamberger’s.” I’ve often wondered if the store’s racism is why James VanDerZee left so quickly. Moving to Newark from Harlem in 1915, he took his first job in the Hahne’s portrait studio as a darkroom assistant and then a portraitist. By 1916, however, he was back in Harlem, setting up his own place— the now iconic Guarantee Photo Studio— at a music conservatory his sister founded in 1911.

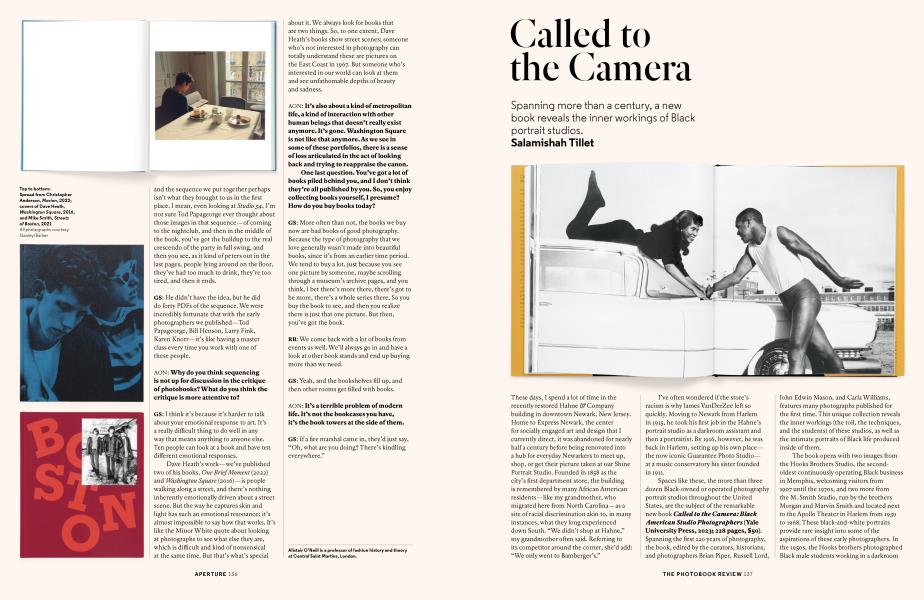

Spaces like these, the more than three dozen Black-owned or operated photography portrait studios throughout the United States, are the subject of the remarkable new book Called to the Camera: Black American Studio Photographers (Yale University Press, 2023; 228 pages, $50). Spanning the first 120 years of photography, the book, edited by the curators, historians, and photographers Brian Piper, Russell Lord, John Edwin Mason, and Carla Williams, features many photographs published for the first time. This unique collection reveals the inner workings (the toil, the techniques, and the students) of these studios, as well as the intimate portraits of Black life produced inside of them.

The book opens with two images from the Hooks Brothers Studio, the secondoldest continuously operating Black business in Memphis, welcoming visitors from 1907 until the 1970s, and two more from the M. Smith Studio, run by the brothers Morgan and Marvin Smith and located next to the Apollo Theater in Harlem from 1939 to 1968. These black-and-white portraits provide rare insight into some of the aspirations of these early photographers. In the 1950s, the Hooks brothers photographed Black male students working in a darkroom and selecting prints. Lord writes in the book’s introduction that such images are about “looking and making, labor and education, the individual and the collective, devotion and joy.”

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

Likewise, the images made in the Smiths’ studio from the previous decade— the first featuring a Black woman photographer setting up to shoot her model, or another by Austin Hansen of Morgan Smith himself standing on a lamppost in Harlem with a Speed Graphic camera in hand—underscore how these institutions were also unique places of artistic experimentation and archival documentation.

Like the photographs that follow, these earliest examples also remind us of the organizations’ critical role in the larger battles over racial representation and the photographic gaze.

When African Americans sought a Black portrait studio, they wanted professional photographs that captured them with dignity and respect and, in doing so, countered the preponderance of racist imagery in American society. This meant that the photographers for whom they sat, dating as far back as the mid-nineteenth century, to portraitists such as Pennsylvania’s Glenalvin Goodridge (whose father had been enslaved) or Virginia’s James Presley Ball, had to not only master the newly invented form, techniques, and equipment of photography itself but simultaneously innovate the field by opening it up to Black subjects.

Abolitionists understood the power of this new medium. Sojourner Truth sold cartes-de-visite of herself at lectures to make a living. Frederick Douglass sat for more than 160 photographs, many of them individual portraits, becoming the most photographed man of the nineteenth century. They believed that these images’ realism could accurately reflect their humanity back to the world and be an essential weapon in their fight to end slavery. W. E. B. Du Bois recognized that the photographer’s identity and political inclinations were as important as the print itself. “The average white photographer does not know how to deal with colored skins and having neither sense of their delicate beauty of tone, nor will to learn, he makes a horrible botch of portraying them,” he wrote in 1923 in The Crisis, the journal of the NAACP. “From the South especially the pictures that come to us, with few exceptions, make the heart ache.”

Photographers and their clientele shared a mission: to portray Black people in the best light possible.

So within this racial milieu of a segregated nation and a racially biased photography tradition, the necessity of the Black portrait studio took on heightened urgency. Unlike the vaudeville stage or the movie or recording studios, which were mostly white-controlled, Black photographers and their Black clientele exercised unique artistic and commercial authorship over their images. They often shared a similar mission: to portray Black people in the best light possible. And as more and more Black portrait studios opened around the country, the style, purpose, and circulation of these images began to vary even more, with photographers picking up fashion, advertising, and documentary work.

We see much of this variety in the pages of Called to the Camera. Pulling from vast archives, the book includes single portraits such as Ball’s daguerreotype from about i860 of his brother-in-law, VanDerZee’s 1924 gelatin-silver print of Marcus Garvey, or an image of the singer A1 Green in the Hooks Brothers Studio from about 1968.

They are alongside group shots such as a panorama of young Black doctors watching a surgery in an operating theater at the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC, made by Robert Scurlock in his own studio in 1950, or class pictures taken at George W. Carver High School in Memphis. The book’s move from the individual to the collective, from the interior to the outside, and staged versus candid, is intentional.

We learn that the Black portrait studios were the primary shapers, teachers, and producers of Black respectability aesthetics. But I also wondered if there was room for artistic experimentation beyond these social and political concerns. In some ways, images of Black photographers working—fixing a smiling model’s hair, smoking cigarettes while selecting prints, or quietly meditating in the darkroom— break from this pattern of stateliness by revealing the vitality and joy that went into their process.

Mainly, these portraits were shared among family members. Occasionally, they were made for or put on public display. “We weren’t selling messages to white people,” the Memphis judge D’Army Bailey is quoted as saying in an essay by Piper.

“We were sending messages to each other, sharing evidence of our vision of ourselves to our friends and family and carrying those visions forward to prosperity... photography provided an extension of ourselves at our best.”

Given this imperative, images that complicate our preconceptions of respectability in general and of Black women’s sexuality intrigue me even more. Three very different examples stand out.

An unknown photographer’s hand-tinted tintype from about i960 of a Black woman— in a luxurious silk striped dress, her hair half smoothed back while the rest loosely falls on her shoulder—feels both highbrow and casually elegant. Another, a gelatin-silver print by Allen E. Cole titled Portrait of a Woman, seated, from about 1925, shows a woman in a strapless silk gown and a fingerwave updo, her bare left arm leaning in, her back partly exposed, her gaze both straight ahead and a bit sultry. Did the photographer elicit such a response? Or did the woman add this flair and sexual appeal all on her own?

The boldest is, of course, one of the more recent. Carla Williams’s 1985 selfportrait features her in a bra, her formerly pin-curled hair now relaxed, her eyes looking downward, and her left hand holding up a robe while her right grasps the cable release. Her essay in the collection hints at the purpose of these images for the sitters as well as for their artists. “We make photographs because photographs make us matter,” she writes. “So we primp, we prance, and in the blink of an eye, we strike the pose.”

Salamishah Tillet is a contributing critic at large for the New York Times. She was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 2022.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

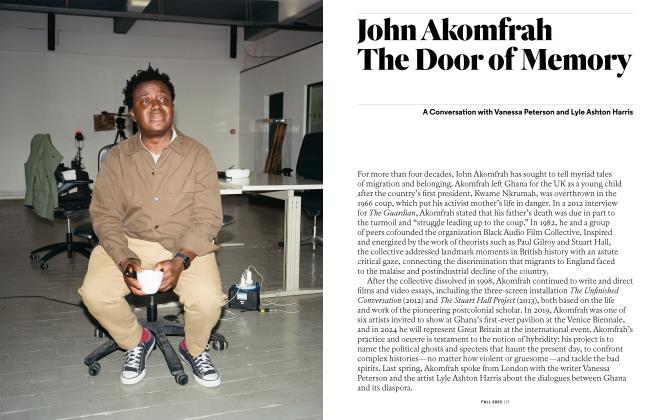

John Akomfrah The Door Of Memory

FALL 2023 By Vanessa Peterson, Lyle Ashton Harris -

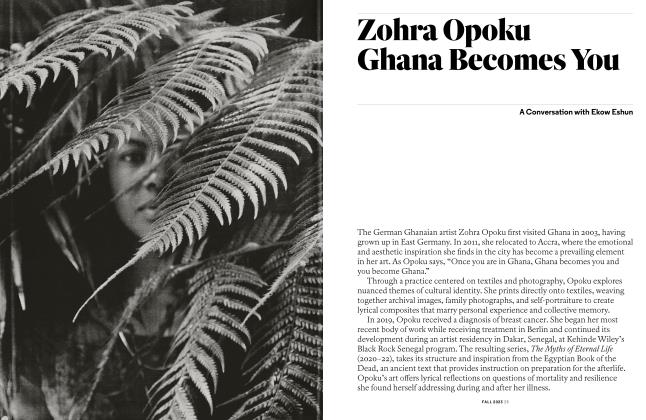

Zohra Opoku Ghana Becomes You

FALL 2023 By Ekow Eshun -

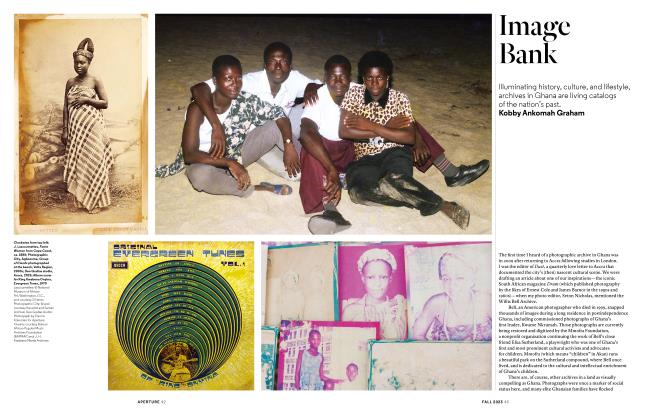

Image Bank

FALL 2023 By Kobby Ankomah Graham -

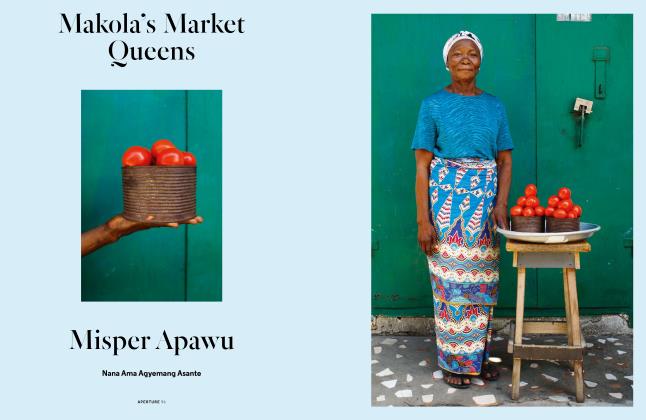

Makola's Market Queens Misper Apawu

FALL 2023 By Nana Ama Agyemang Asante -

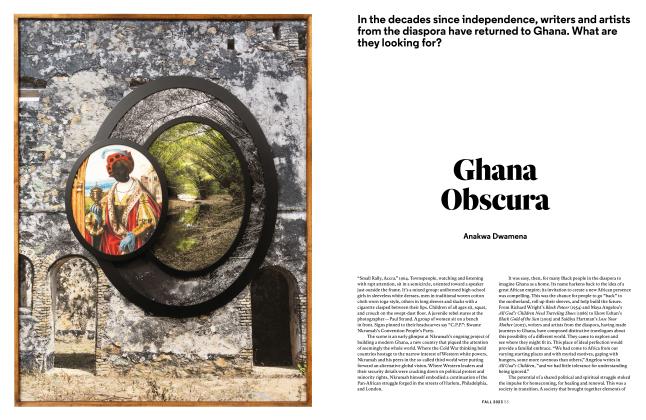

Ghana Obscura

FALL 2023 By Anakwa Dwamena -

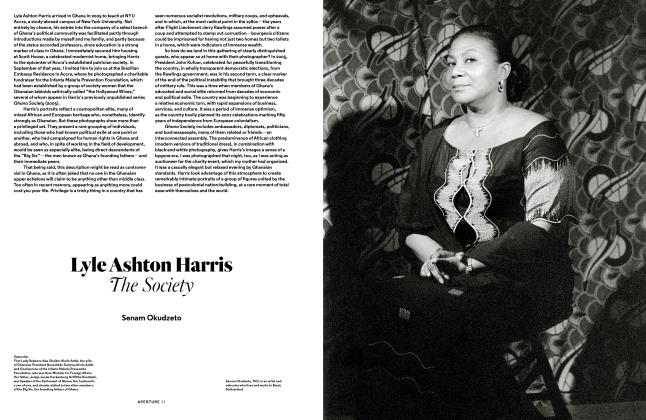

Lyle Ashton Harris

FALL 2023 By Senam Okudzeto

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

Salamishah Tillet

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

-

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

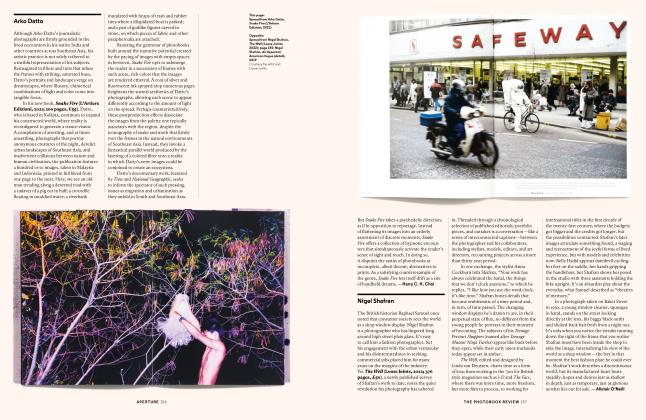

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWArko Datto

FALL 2022 By Harry C. H. Choi -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWMagazine Culture

SUMMER 2023 By Lena Fritsch -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

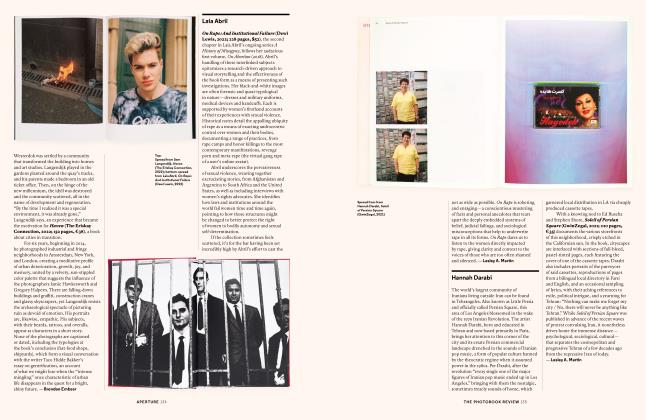

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWHannah Darabi

SPRING 2023 By Lesley A. Martin -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWNancy Holt and Richard Misrach

WINTER 2022 By Lucy McKeon -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

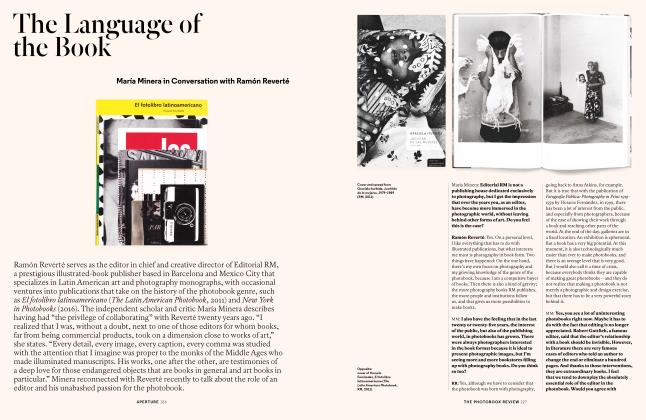

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWThe Language of the Book

WINTER 2022 By María Minera -

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEW

THE PHOTOBOOK REVIEWKenta Nakamura

FALL 2023 By Noa Lin