Bieke Depoorter Conversations with Pictures

For the Belgian photographer, documentary is a listening exercise and a form of investigation, as she builds relationships with her subjects, blurring the lines between authorship, fiction, and truth.

Thessaly La Force

In fall 2022, the Belgian photographer Bieke Depoorter was in New York for a group show, Close Enough: New Perspectives from 12 Women Photographers of Magnum, at the International Center of Photography, where portions of her yearslong project Agata (2017-20) were on display. From there, she planned to travel to California and Oregon to continue her work on another ongoing project, begun in 2015, called Michael. Both are visual studies of a person Depoorter is interested in photographing—Agata Kay (her last name is a pseudonym) is a performer and former sex worker who Depoorter encountered in Paris in 2017; Michael is an elderly man whom Depoorter struck up an unlikely acquaintance with on the streets of Portland in 2015—but both are also about the complex and uncomfortable ways a photographer can become enmeshed in the life of her subject. “I don’t really pick my projects,” Depoorter tells me. “They happen to me. They become part of my life and that can become very overwhelming.”

At thirty-six, Depoorter possesses a quiet confidence that makes it possible to understand how someone would be at ease with her when she’s behind the camera. Ever since she began taking pictures, Depoorter has been preoccupied with the ethical questions surrounding the art. What is exploitative?

What is purely in the self-interest of the photographer? “In school, I always felt very uncomfortable photographing someone on the street without their consent,” she says. “I really love documentary-style photography, but I always had a feeling that I was stealing images of people. I want to have a relationship with the people I photograph. It can be a short relationship; it’s not as though you need to build a friendship. I see making pictures as a conversation.”

What this conversation looks like, and how long it will take, is entirely dependent on the dynamic between Depoorter and her subject. In the case of Agata, Depoorter was on assignment for Magnum Live Lab in Paris, a residency hosted by the Magnum Photos agency, and struggling to regain her footing as an artist.

She had just broken up with a boyfriend and was having a hard time. After being invited to a strip club by a doorman she had become friendly with, Depoorter met Kay, who was working that night. Their encounter began an involved and complicated relationship. The two would eventually travel together, as well as engage in an honest and philosophical epistolary exchange about the pictures they were generating, with Kay even contributing her own ideas and opinions to Depoorter’s exhibitions. In 2021, Depoorter published a book about Kay that contains not only her photographs but both of their observations of how their relationship has changed by the force of Depoorter’s lens and how it presents Kay to the world.

In Agata Kay, Paris, France, November 2, 2017, a striking image from the day after their first meeting, Kay stands in front of a fuchsia-pink wall, in a loose bodysuit of the same color. Her hands rest on the bottom hem, along the pubic line, a gesture that suggests exposure, as if she might remove the article of clothing. But her pose is not one of seduction—the expression on her face is at once confronting and vulnerable. Depoorter seems to be asking: Who really is Agata Kay? Kay the sex worker is different from Kay the performer, who is different from Kay the person, who is different from the Kay that Depoorter reveals in her work.

“The picture can never be true,” writes Kay at one point. “Neither is it a lie. It is just a carefully selected excerpt of what is a point of view.” That Agata is mutable—never fixed with one image, one show, one voice, or even one book—appears to be what Depoorter finds so exhilarating and challenging about photography. The impossibility of capturing the true Kay through one picture is precisely the point.

Depoorter was born in 1986 in the town of Kortrijk, Belgium, the second of three children, to an electrician and an elementary school teacher. Growing up, she was not exposed to much art or photography, but as an adolescent she came into possession of a digital camera. The first photographs she took were of her pet guinea pigs alongside her younger brother’s toys. When Depoorter was eighteen, she enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, in Ghent. Her mother had made her take an aptitude test to help determine what kind of profession she might be suitable for as an adult; it had suggested educational sciences, which terrified Depoorter enough for her to stake a claim in the arts: “I thought, Okay, I need to take my life in my hands because otherwise I will be stuck forever.”

At the Royal Academy, where Depoorter received both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, she felt comfortable among the artistic and creative milieu of the program. Her 2008-9 thesis project, Ou Menya—which would also become her first published work—was the product of three month-long trips through Russia along the Trans-Siberian Railroad. Due to the region’s few hotels, Depoorter’s own lack of funds, and her inability to speak the language, she approached strangers in the towns with a note in Russian that read: “I’m looking for a place to spend the night. Do you know someone who might have a bed or a sofa?

I don’t need anything special and have a sleeping bag with me.

I don’t want to stay in a hotel because I have little money and I want to see how people live in Russia. May I sleep at your home? Thank you for your help!” This request gave her the opening she needed as a photographer. In the privacy of people’s homes, Depoorter was able to witness deeply intimate moments— teenage girls performing rhythmic gymnastics in their underwear; a young mother calmly smoking a cigarette next to her two rambunctious children—that quietly reveal not just the poverty and starkness of Siberia but the warmth and generosity, the despair and resignation of the people living there. For the first time, Depoorter was comfortable with her role as photographer. “Despite the language barrier, I suddenly had a relationship with the people I was photographing, which I had missed before,” she explains.

“I don’t really pick my projects," Depoorter tells me. "They happen to me. They become part of my life."

Her student years, Depoorter felt, had been more about her trying to be someone she wasn’t. “I might have seen a scene on the street, and I’d be very focused on finding the perfect composition.

I would have created the image in my mind, and I would stay out on the street for an hour or more just to make this image. But I always had the feeling when I got back home and looked at the photograph that it lacked something,” she says.

OuMenya established Depoorter in the photography world.

In 2012, at the age of twenty-five, she was asked to join Magnum. Subsequent works of hers, such as I Am About to Call It a Day (2010-14) and As It May Be (2011-17), follow a similar vein: in both, Depoorter set herself in a foreign country (the United States and Egypt, respectively) and found ways to stay in the homes of complete strangers, photographing the people and landscapes she came in contact with, often over the course of several years. With As It May Be, Depoorter evolved the concept. She had become increasingly uncomfortable with her own power as the photographer, and when she returned to Egypt one last time—it had become more and more difficult for her to travel there after the Arab Spring—she brought a mock-up of the book she had been planning to publish from these trips but then put aside. “I had started to feel like an outsider,” Depoorter recalls. “Did I make a book from a Western point of view? The photographs I took were not an accurate reflection of Egyptian life. They didn’t show much of the revolution and the complexity of the country. Wealthy people, for example, didn’t welcome me into their homes, and many people refused to be photographed.” It was there, with a mock-up she felt she had no right to publish, that Depoorter decided to ask Egyptians to write their thoughts on top of her images. Her work became a medium for exchange. “The book is really beautiful and wonderful,” reads one person’s comment, “but there are not enough images that show happiness.” Another: “I think you should start the book all over again. Take pictures that express something and are about Egyptian civilization.” For Depoorter, allowing her pictures to be critiqued, commented on, and even defaced by the pen was a solution she hadn’t realized existed before. “Photography alone felt so limiting, and the use of text opened a whole new conversation,” she says. It was a liberating discovery, one that would push her art to new levels.

In May 2015, Depoorter was in Portland, Oregon for another Magnum project when she met Michael. He had bipolar disorder; he told her that he had no phone or internet and was fond of walking by himself for hours a day. Michael agreed to let Depoorter photograph him, and they ended up spending the afternoon together. During her remaining days there, Depoorter visited Michael two more times. He invited her into his apartment on each occasion, and they looked at his belongings, mainly pictures he had saved from his life, magazine clippings, and books. “I got most of those pictures out of magazines,” he told her in a recording she made at the time. “But I tried to put them in ways that would make sense out of them.... They aren’t just hodgepodge pictures that don’t go together. They go together.” Depoorter instinctively understood that Michael felt comfortable making sense of reality through images and writing, much in the way she did as an artist. “His collages were created by someone with a keen sensitivity for peculiar beauty,” Depoorter observed. In one photograph by Depoorter, Michael is in his apartment. His walls are covered in a seemingly haphazard array of images, some imperfectly cropped from magazines, others framed, crowded together along whatever space he finds. Yet Depoorter’s empathy is powerfully present in the image. The disarray that betrays Michael’s unwillingness or perhaps inability to conform to societal notions of presentation within the home doesn’t appear chaotic. If no one else was listening to Michael, Depoorter was.

Depoorter returned home to Ghent, Belgium, and continued on with her life and her work. She sent Michael postcards and a letter from her travels, but that was extent of their communication. Shortly after their time together, Michael sent her a small suitcase filled with more pictures, clippings, and other ephemera (during her visit with him, he gave her a briefcase and another suitcase that she had photographed and returned). But time passed. Depoorter had been busy on the road. A year later, she finally went through Michael’s briefcase, where she found a letter from Michael asking for her help. Concerned by his subsequent silence, Depoorter decided to return to Portland in the spring of 2018 to speak to him face-to-face. But Michael had been evicted from his apartment and no one had seen him since. So Depoorter began to search for Michael herself, documenting what she discovered, including his former apartments and other places where he had resided throughout his life. She visited and photographed scenic destinations he had included in his scrapbooks, such as Mount Hood and Lost Lake. She spoke to people who had gone to school with him. She even attended a graduation at his former high school. “I wanted to understand the links he made and understand his past. I didn’t want to judge him; I just wanted to understand his life,” Depoorter says.

She has shown portions of Michael and has made several compelling short films that include her audio interviews with Michael and the people who knew him, but as of yet the project is incomplete. This work is less a dialogue between subject and author and more a detective story, one in which Depoorter is fully allowing herself to try to see how close she can get to Michael’s experiences and feelings, piecing together his life from whatever she can find and repeating his movements in a gesture toward proximity. What began as a kind of listening exercise, an attempt to hear Michael and view him uncritically, is now something else. It is as though Depoorter is no longer trying to find Michael, who perhaps doesn’t even want to be found. The piece has become, in many ways, a manifestation of Depoorter’s own obsession. “I felt lost,” she says in one of the films. “I didn’t remember what I was looking for.”

Depoorter instinctively understood that Michael felt comfortable making sense of reality through images and writing, much in the way she did as an artist.

At one point, while parking her car close to one of Michael’s childhood homes near Yosemite National Park, she sees an object flash briefly in the night sky. Is it a UFO? Something else passing by? Her images of it are blurry, but something uncanny-looking is there. She has a recording of her speaking to a man fishing nearby. The two are in shock, even jittery with excitement at what they have just witnessed. With Michael, Depoorter allows herself to be drawn into the abnormal. The result is peculiar but also isolating and unusual. Depoorter seems to retreat to somewhere that is about neither Michael nor herself, lost to the mystic beauty of the West Coast’s natural landscape and its vast wilderness.

It will be interesting to see what Depoorter—still very much in the middle of her career—will do next. Her preoccupation with narrative and storytelling, particularly the suspense that drives Michael, reminds me of films by the Austrian director Michael Haneke and the work of the French artist Sophie Calle. Depoorter cites the influence of Magnum photographers such as Jim Goldberg and Susan Meiselas, both artists who have helped canonize the act of collaboration within the form. She admits that her fascination documenting events in her life can be overwhelming—for a while, she compulsively recorded her own banal or private moments. “If something happens, and if you don’t have a picture or a recording, did it happen?” Depoorter asks. “Maybe people don’t believe you, but at the same time, perhaps a picture is not everything. I don’t believe pictures either.” Depoorter’s work confronts the established authority of the author of the photograph. She pushes against the boundaries of what is seen as the truth. By seeking a dialogue with her subjects, she invites questioning. Where is the reality? Can there be an objective point of view?

Depoorter describes the camera as an incredibly powerful tool. It can serve as a shield, as a form of memory, as a way into an inhospitable scenario or situation. It also offers her perspective on what can feel too close. “I pick up my camera, and I start to film and to photograph. It helps me observe myself,” she says. “You become an actor in your own life, where you can deal with certain feelings. You can distance yourself from emotions when you start to make something.” What the end result will look like is always uncertain. But Depoorter will capture it, no matter what.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

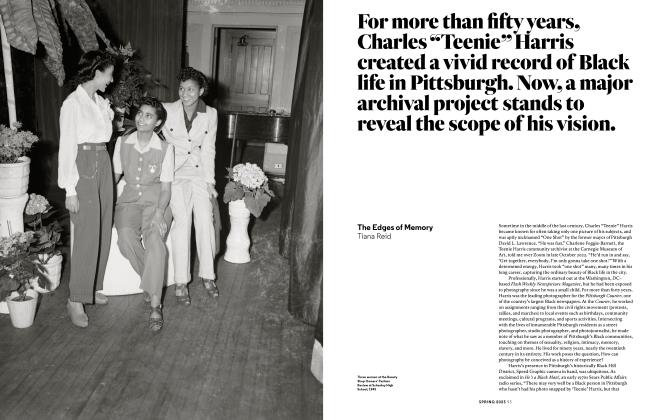

The Edges Of Memory

SPRING 2023 -

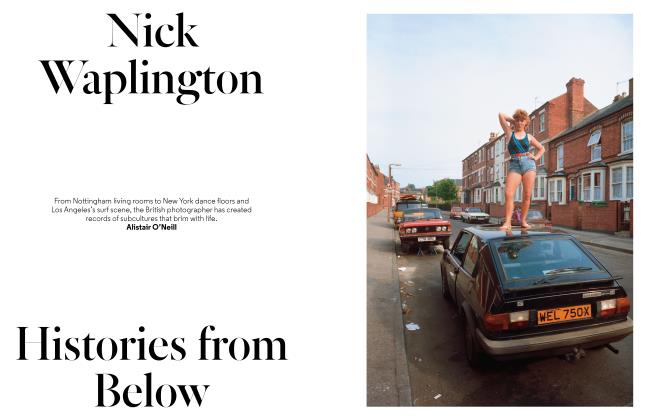

Nick Waplington Histories From Below

SPRING 2023 By Alistair O'Neill -

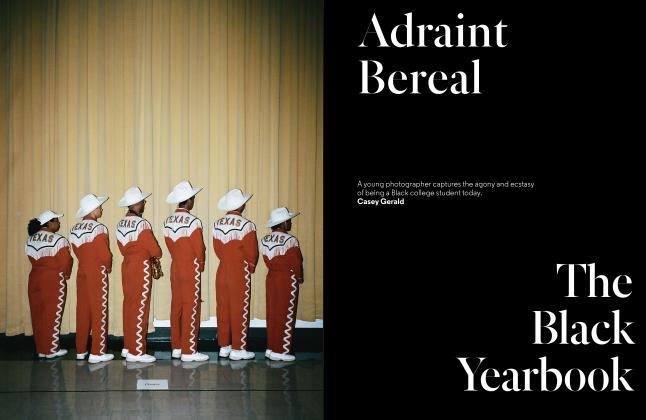

Adraint Bereal The Black Yearbook

SPRING 2023 By Casey Gerald -

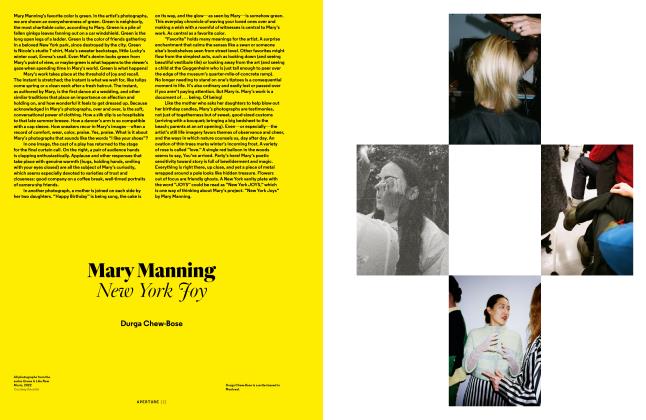

Mary Manning

SPRING 2023 By Durga Chew-Bose -

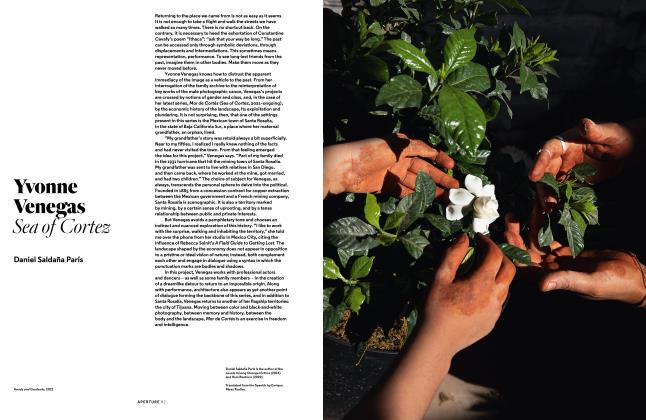

Yvonne Venegas

SPRING 2023 By Daniel Saldana París -

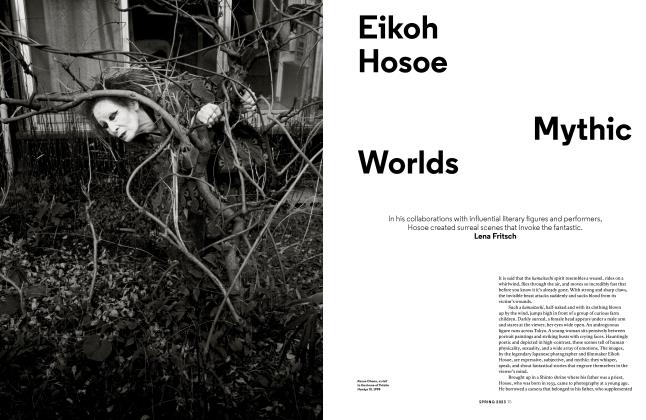

Eikoh Hosoe Mythic Worlds

SPRING 2023 By Lena Fritsch