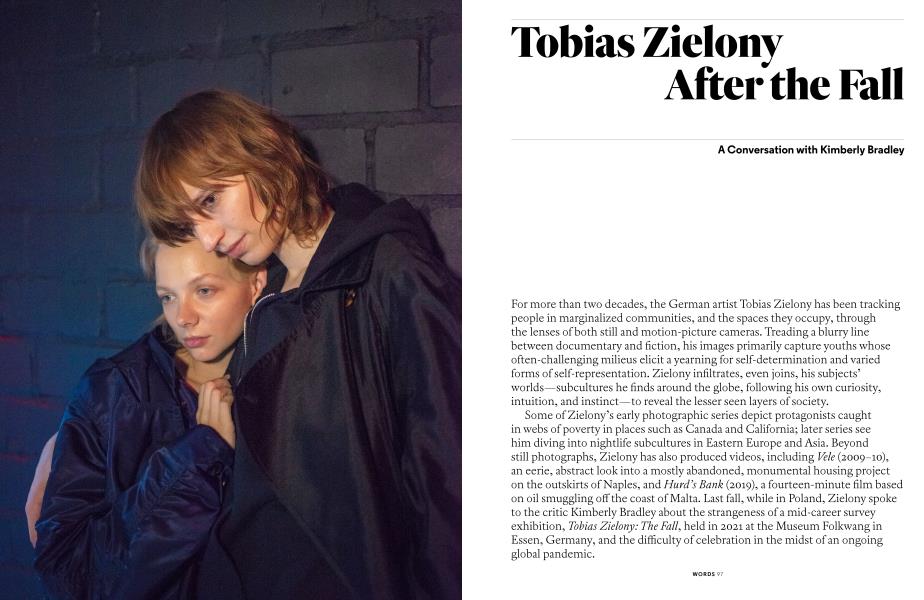

Tobias Zielony After the Fall

A Conversation with

Kimberly Bradley

For more than two decades, the German artist Tobias Zielony has been tracking people in marginalized communities, and the spaces they occupy, through the lenses of both still and motion-picture cameras. Treading a blurry line between documentary and fiction, his images primarily capture youths whose often-challenging milieus elicit a yearning for self-determination and varied forms of self-representation. Zielony infiltrates, even joins, his subjects’ worlds—subcultures he finds around the globe, following his own curiosity, intuition, and instinct—to reveal the lesser seen layers of society.

Some of Zielony’s early photographic series depict protagonists caught in webs of poverty in places such as Canada and California; later series see him diving into nightlife subcultures in Eastern Europe and Asia. Beyond still photographs, Zielony has also produced videos, including Vele (2009-10), an eerie, abstract look into a mostly abandoned, monumental housing project on the outskirts of Naples, and Hurd's Bank (2019), a fourteen-minute film based on oil smuggling off the coast of Malta. Last fall, while in Poland, Zielony spoke to the critic Kimberly Bradley about the strangeness of a mid-career survey exhibition, Tobias Zielony: The Fall, held in 2021 at the Museum Follcwang in Essen, Germany, and the difficulty of celebration in the midst of an ongoing global pandemic.

WORDS

Kimberly Bradley: This issue’s theme is “celebrations”—but you’ve said your work isn’t celebratory, which makes this interview a bit of a challenge! Still, your recent retrospective could certainly be seen as a celebration of your oeuvre thus far: around four hundred people attended the opening last June, a small miracle during a pandemic. How did the exhibition come together?

Tobias Zielony: I was invited by the curator Thomas Seelig, and we decided to look back at the past twenty years of my work. It’s really about going back and coming full circle, starting with early series such as CarPark from 2000 and Curfew from 2001 to Vele about the Scampia neighborhood in Naples. The other point was to have about half of the exhibition space devoted to videos, including Al-Akrab (2014) and Big Sexyland (2006). It was tempting to mount a big photography show, but we decided to add black-box spaces with projections and screens as well; in eleven or twelve rooms, the choreography went from bright to dark in a kind of topography that suits my work, which is so much related to night and darkness.

KB: True, many of your photography series were made at night with protagonists from sex-work or clubculture contexts. But why include so much video?

TZ: Video has become a crucial part of my art, and the videos are related to the photographic still images, meaning they use animation and stop motion. The Fall was a look at a long period of my work, but also about the relationship between still and moving images and everything in between.

KB: What was it like to assemble such an exhibition in your late forties? Retrospectives are interesting for artists, like you, who are not that old.

It must be intriguing to be in a position to reflect on what you’ve done so far.

TZ: It did make me feel a bit older, but we mostly avoided the term retrospective.

Let’s say it was a mid-career retrospective. And we tried to keep it from becoming too retrospective-like: One way was how we designed the space, which had a kind of makeshift quality, using a lot of cheap materials. The other was hosting workshops that activated the exhibition and made it feel current and present. And the third is the catalog, which isn’t a huge brick of a book, like so many are, but rather a series of shorter volumes with essays written by young writers, none older than thirty-three, not necessarily interpreting my art, but...

KB: Adding to it, augmenting it.

Some of the essays are almost literary, responding to specific series in your oeuvre.

TZ: Personally, I think that many photography shows are boring. You come into a big white space and have small or medium-size images along the walls and a big vacuum in the middle. We also tried to present my works that are not the typical photographic series; ones that are more installation based or somehow extend into the rooms.

KB: The Citizen from the German pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015 is one example. Starting in 2014, you followed and photographed groups of refugees and activists struggling for recognition and human rights in Hamburg and Berlin; then you activated newspapers in countries such as Uganda, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Sudan to publish the images of these people with stories of their difficulties. In Venice, these images were shown not as framed portraits but in newspaper format, installed on vertical structures.

TZ: For The Fall, we created a different way of presenting The Citizen that worked well, with vitrines and the large layout images at varying heights on the wall, going high up. It was a condensed, more accessible version of this project. The focus was clearly on the original newspaper articles, which we showed under glass for everyone to read.

KB: Could you talk about The Fall (2021), your recent body of work?

TZ: So The Fall is the name of the overall exhibition and the book series, but it is also the title of this new piece that became an installation. The title came from the beginning of the pandemic—it’s about me falling down a skate ramp while I was photographing, but also this feeling of general catastrophe or emergency. In the main room of the exhibition, we built a kind of wooden stage, or ramp. That was the venue for the workshops, which were all about the idea of falling—falling and standing up again. On the walls were forty-five large inkjet color prints starting at 50 centimeters by 70 centimeters, with the largest being 80 by 120 or so.

They all differed in size and are like copyshop prints, overlapping and forming this kind of frieze along the walls. It had the feeling of something impermanent. The layout, this kind of layering, was a reference not only to the stop-motion films I make, but also to the way we use and perceive social media. Each time we add an image on Instagram, another moves further down. It’s a constantly evolving and selfrewriting archive.

KB: The images include portraits you were commissioned by the French magazine Numero to make of Berliners born after 1989, and photographs from the industrial Ruhr region in Germany, and even the basketball player Dirk Nowitzki’s last season with the Dallas Mavericks, which you did for a book project about him. But also portraits from recent trips. It’s far less discrete than your other series in terms of context or location.

The Fall was a look at a long period of my work, but also about the relationship between still and moving images and everything in between.

There has always been an aspect in my work that looks into what connects people in very different and often faraway places.

TZ: The piece covers the past two or three years, with some exceptions. Archival material or work I’ve done for projects that have not yet been shown in art spaces—but much of it has been seen on my Instagram account—are also a part of it. The images come from diverse places: Korea and Japan, Germany, Malta, Palestine. For the first time, it brings together pictures from various contexts. So, it’s not a series about a specific place or a group of people. It felt liberating to break out of this strict organization. It’s more like a diary. And, of course, there has always been an aspect in my work that looks into what connects people in very different and often faraway places.

On the superficial level, that could be sportswear, or poses related to an increasingly globalizing pop culture.

On a deeper level, we are witnessing the fall of the neoliberal model. It has a more personal archive aspect as well: my nephew and brother are both pictured. It was beautiful to see pictures that normally would be single images not connected to any series, and I could edit them in. There was a long, almost meditative process during the lockdown in which I arranged the images on my studio wall, but there is no coherent narrative. It has the feeling that the narrative is never-ending, or it’s just updating itself. Maybe that’s what I was trying to achieve.

KB: Much of your work is not just about the lines between documentary and self-representation but also indirectly critiquing media representation. You chose to include a Super-8 film as part of the installation.

TZ: There’s a screen standing on the floor with transferred Super-8 footage, and all of the scenes in the film, Apollo (2021), are running backward. I made it almost a diary of 2020. It ends with New Year’s Eve 2020-21, with fireworks, but the fireworks fly backward, and skaters fall but then stand back up, and the water cannons suck in water. In it are also demonstrations in Berlin against COVID-19 restrictions. Are we going toward the future or back in the past?

Are we going into a better future or something else? In this sense, the Super-8 film is anything but nostalgic.

KB: This idea of falling and standing up reminds me of the essay by Joshua Gross, one of the writers in the first volume of the exhibition catalog.

He refers to the opening scene in Werner Herzog’s film Heart of Glass in which a character talks about tumbling deeper and deeper but then falling upward. He also references the writing of the philosopher Marcus Steinweg, with Gross stating that “falling can have a subversive power.” I sometimes wonder if, in your work, you’re searching for a kind of liberation from social oppression.

TZ: I’m from a generation that’s torn between having this upbringing in West Germany as a child where there was still the idea that the world is getting better, and we’re all safe, and our parents are happy, and we have good politicians. There was a short period when a large part of the population thought that things were okay. Maybe it was just an illusion from the beginning. But, then, we were hit hard, of course. The punk movement was one of the voices to declare there was no future, and then turned destruction or negation into something subversive or liberating. I am not sure if that’s really the case, but I grew up feeling that it’s good to rebel and oppose. That’s what we see happening right now. As a teenager, I worked at punk concerts, and, sometimes, my job was to be onstage and throw people back into the crowd. I appreciate this kind of feeling that it’s okay to struggle or to fall. And, it’s also important to help other people out.

KB: Gross also mentions the “depressive hedonia” concept from the cultural theorist and philosopher Mark Fisher in his 2009 book Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?

It’s not about the inability to achieve pleasure, but rather the inability to do anything but pursue it. There’s some celebration within the hedonism implied here.

TZ: People see my work and often say,

“Oh, it’s depressing” but it was never depressing for me. I maybe even felt it to be more like something liberating.

We’ve spoken before about the boredom that I try to capture in these social groups, but once you’re immersed in a “bored” state of mind or lifestyle, this lack of events might become enjoyable or hedonistic.

But it has some more problematic aspects. Mark Fisher is between those poles.

Of course, now we can say pleasureseeking is very much related to neoliberal capitalism, or of leaving people not in the workforce out of the picture; it turns them into pure consumers. It’s not so easy to celebrate that, but from my perspective, it was more about looking at the subversion or rebellion—of not doing what you’re supposed to do.

KB: I wonder if there’s anything to celebrate right now as we head into another pandemic winter in Europe, and the continent is faced with increasing political upheaval. You’re in Warsaw at the moment, talking to locals about the political situations there, exploring a potential project. Politics are unstable, but there’s a strong sense of solidarity among the people. Could you talk about works in progress?

TZ: There’s one project in BitterfeldWolfen, Germany, where the ORWO film factory used to be, which I can’t speak about quite yet but involves unemployed people from the factory, older people.

And then I’d like to be more in Poland, if possible. The general situation in Poland is similar to that in other European countries where there’s a turning toward a weird control of the media. There are threads that are alt-right and neofascist, and there’s toxic masculinity, but there’s also a very neoliberal kind of direction. At the same time, in Poland, there’s a lot of resistance from the people. One aspect I’m interested in is the forest on the border with Russia, where migrants are trying to enter from Belarus through a wooded area. I don’t know if I’ll follow up, but that’s also why I’m here talking with people involved in a movement to protect the same forest. There are fights between environmentalists and the logging companies. A new project could come out of this. I’ll see.

KB: The earliest phases of your work are quite similar to those of investigative journalists, even if your methods thereafter are different.

TZ: I talk to people, and I find out what’s going on as well as I can, and go along with that, and then try to link local communities or grassroots movements.

It could also be a party culture: some of my series focus on club kids and techno.

But this happens within a bigger framework that also relates to things on a level that makes sense in places outside Poland.

I went to an outdoor performance of a queer collective and also accompanied a friend to a demonstration as well as the workshop preparing banners for the event. I had my camera with me but that is not the most important part.

KB: I’ve been asking one question in almost all the interviews I do lately:

Are you optimistic or pessimistic about the current global situation?

TZ: I am actually quite pessimistic. I’m not opening the door and thinking, Oh my God, the world is going to explode. But if I’m pragmatic, I don’t see a good ending. Major crises will be coming up soon in terms of climate change but also politically. I worry about the ignorance that’s governing public discussion, about how politicians chase this minority of cynical, nonempathetic, toxic people. In the United States as well as in Germany, Austria, and Poland, for sure, these people have this feeling that now is their time to speak up for revenge against whatever they consider to be liberal. I’m worried about that. I don’t even know if it’s about democracy: the crisis is more general and democracy is no longer able to pacify large parts of the population. Maybe being here in Poland makes me more worried.

From my perspective, it was more about looking at the subversion or rebellion—of not doing what you’re supposed to do.

The same with the pandemic. Beyond what we think is truth, or what the pandemic is about, we just open the gates to all kinds of fantasies. It’s almost like children who don’t want to know what’s going on.

KB: I worry, too, but I have moments of optimism in which I see a critical mass building of people who were complacent before. Now, they’re activating to not only preserve the better parts of democracy but also, and more importantly, to think of new systems that might work better.

TZ: I agree with you. Of course, I’m on the side of the people who think that it is time for a change now more than ever. But I wonder if we are strong enough or radical enough.

KB: Things are not going to be easy. Can we find other ways to celebrate?

TZ: There’s nothing wrong with celebrating and coming together. I don’t even think we always need reasons to do so. I see it more in the social aspect rather than celebrating one hundred years of this or that. We rely on looking back at our lives, and the lives of our friends—appreciating the things we’ve been doing together in whatever ways— and working toward a future focusing on care and solidarity.

Kimberly Bradley is an art critic and writer based in Berlin. She is the Berlin correspondent for Monocle magazine, and her work has appeared in ArtReview, Frieze, PIN-UP, and the New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

Subscribers can unlock every article Aperture has ever published Subscribe Now

WORDS

-

Words

WordsHigher Ground

Spring 2016 By Alexander Stille -

Words

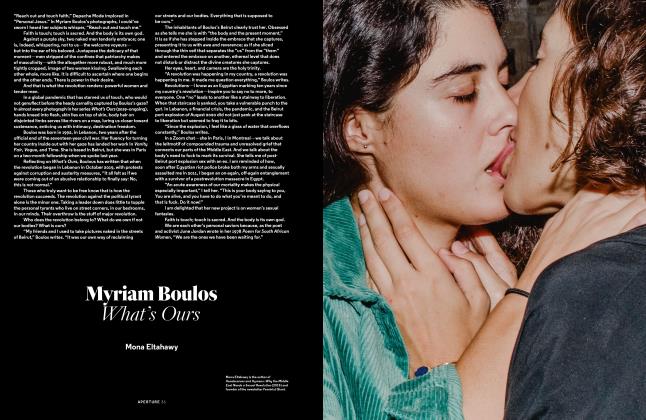

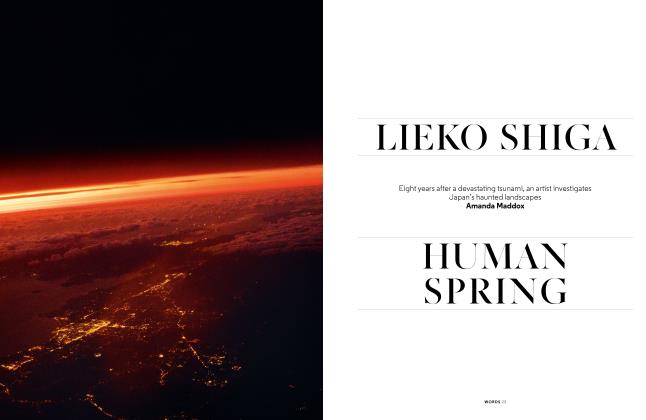

WordsLieko Shiga Human Spring

Spring 2019 By Amanda Maddox -

Words

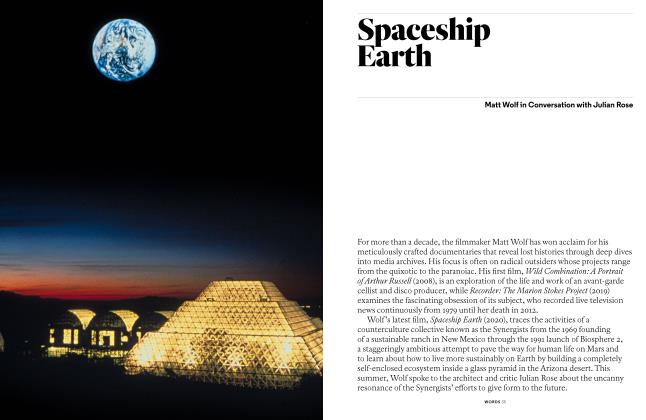

WordsSpaceship Earth

Winter 2020 By Matt Wolf -

Words

WordsPhotography And Its Citizens

Spring 2014 By Nato Thompson -

Words

WordsNoni Stacey On Women & Work, London, 1975

Winter 2013 By Noni Stacey -

Words

WordsPrison Index

Spring 2018 By Pete Brook